If it isn't safe, it isn't food.

Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations

In Pakistan, food vendors with small carts or bicycles selling various food items are a common sight outside of schools. Their food products can range from ice cream to sweetened beverages, colourful ice-lollies to fried crackers, and cut vegetables or corn cobs smeared with a mix of spices. Children would gather around these vendors after school to purchase these snacks at low prices. These food purchases are completely unregulated; vendors directly handle and store foods with complete disregard for any hygiene standards. It is not just schools: many streets in urban areas in low- and middle-income countries feature street-food vendors selling food products without any consideration of cleanliness or food safety standards.

One would argue that it is common knowledge to not consume visibly unhygienic food. However, food safety is a collective effort. Along with the consumers, the food vendors also have to ensure that the food items they sell are prepared, stored, and cooked cleanly. But it is almost impossible to ensure compliance with standard protocols unless there are (1) laws and regulations in place that bind people to follow food safety and hygiene rules, and (2) food safety authorities and regulations in place that enforce these laws and ensure accountability.

The food we consume every day is not just a product of different ingredients, smells, tastes, and textures. It may also contain chemicals and a host of bad microorganisms that can make us sick, like bacteria, viruses, and parasites.

As important as it is to ensure that the food we feed our bodies is nutritious, environmentally sustainable, and tasty, it is equally important to ensure that it is safe for our health.

Food safety issues are unfortunately lost within food and public health discourse and do not receive as much attention from policymakers. For example, there is no sustainable development goal indicator on food safety. How is it possible to achieve food security and improved nutrition, as stated by SDG2 ‘Zero Hunger’ if there is no consideration of food safety?

Food safety is a standard that ensures that the food and beverages we consume are hygienic and safe for consumption. Food can get contaminated at any stage along the food supply chain from the air, water, soil, and unsafe handling practices. Food safety steps ensure that harmful pathogens in food are eliminated along with the risk of any infection.

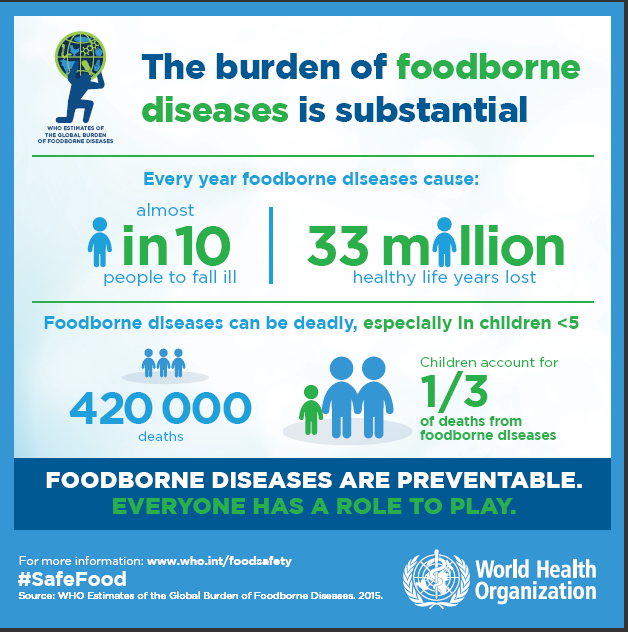

Food that does not meet food safety standards can cause food-borne illnesses. These illnesses can range from diarrhoea to cancer. The most common illness is gastrointestinal, but other systems of the body may also be at risk. Low- and middle-income countries and children under the age of 5 bear the brunt of food-borne illnesses. Children under 5 make up 40% of those affected by foodborne illnesses and 30% of related deaths.

In 2015 – just six years ago – the World Health Organisation (WHO) published estimates of foodborne diseases for the first time. According to the data, 1 in 10 people globally got ill from contaminated food, resulting in 600 million illnesses and 420 000 deaths.

The health burden of foodborne disease (33 million DALYs) is comparable to the ‘big three’ infectious diseases: HIV/AIDS (92 million DALYs) malaria (55 million DALYs) and tuberculosis (44 million DALYs).

(Note: DALY (Disability/Disease Adjusted Life Years is the sum of years lost due to disability, ill-health, and early death).

Unsafe food also costs low- and middle-income countries about USD 110billion per year in terms of medical expenses and productivity loss.

As consumers of food, we use our senses, such as smell and sight, to determine whether the food we consume is safe or not. However, we are often unaware of where the food item is coming from, how many hands handled it, whether it was in contact with poisonous and/or toxic elements along the supply chain, etc.

Many countries have (and should have) food laws and regulations in place that determine food safety standards throughout the food supply chain, from the farm level to the preparation stage. Some examples include requirements to provide information on food packaging about contact with allergens; print the manufacturing and expiration dates of the product; state that the food is not a breast-milk substitute or suitable for pregnant and lactating mothers; list additives; prohibit the use of harmful chemicals at the farm level and determine safe food storage temperatures and packaging requirements.

It is worth mentioning that clean drinking water is a crucial part of food safety. About 2 billion people use a drinking water source contaminated with faeces. Needless to say that water is an important element in the preparation of food as well, and contaminated water causes more than 800 000 deaths each year.

Ensuring food safety requires a collective effort, from the farmer producing or rearing the food, to the industrialists, transporters, retailers, and buyers, to those preparing food, to policymakers, regulators, and local enforcers. It also demands a consciousness movement to put public health over profit and provide people with food that is safe and healthy.

Informal markets – such as the food vendors outside schools in Pakistan and primarily widespread in low- and middle-income countries – pose a challenge for food safety. Many people purchase food and drinks from these vendors and there is nobody to oversee the hygiene standards. If proper regulations existed, government agencies could train workers to enforce food safety standards in both formal and informal settings.

It is also critical to raise awareness amongst consumers and policymakers on the importance of upholding food safety standards. This includes educating consumers on toxic food and associated harm, how to read food labels – including looking for harmful ingredients (additives, colours, etc.) –and how to handle food at home (i.e., cooking, washing, separating meat to avoid cross-contamination, and maintaining food temperatures).

Given that we have an abundance of evidence about the impact of foodborne diseases, governments need to implement central food safety authorities that can function autonomously without the influence of the food industry and businesses. Similarly, it is important to have a disease surveillance system in place to help locate possible outbreaks of foodborne illnesses and thus prevent these from spreading.

Food safety is everybody’s business, and it is a major threat to public health. It is time food safety gets its due attention in legislative, policy and public health spaces.

More from Naina Qayyum here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.