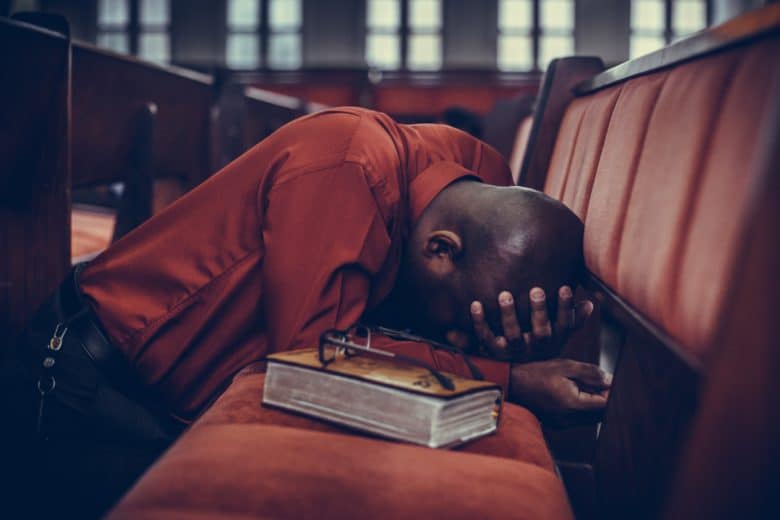

I’ve heard people say the story of our lives is best told in the snapshot of those who show up for our funeral. Final services for members of the LGBTQ+ community in the South are often layered with stigma and controversy. Due to grief (and sometimes denial), families often eulogize the person in a way that is more reflective of who they wish the person was (rather than who they actually were at the time of their passing).