Kuzhikkat P, Ma N, Osorio C, Ahmed N. How can learnings from he automotive industry preventt deterioration of maternal health during a pandemic like COVID-18. HPHR. 2022;66. 10.54111/0001/NNN6

What does a shop floor of automobile companies, pregnant women, and public health have in common? Any senile person wouldn’t be able to draw a correlation. A creative genius may suspect a safety video of sorts explaining the safety hazards of the shop floor to pregnant employees, but that’s by a longshot. However, when our cross-functional team sat together over some tea and cake and pondered how to pandemic-proof expecting mothers, the link between the three became more evident.

While the direct effects of COVID-19 on maternal health are documented, the literature on indirect effects is still non-substantial. Thus, we decided to look at the previous pandemics and endemics that have ravaged humanity, like Ebola, to identify the barriers to maternal health. Mistrust and fear, constraints in the health infrastructure and poor communication were identified as amongst the top three obstacles to maternal health1. What made it even more worrisome is that there was a sharp reduction in regular visits to health centers during the endemic in some countries like Guinea, and these numbers sadly stagnated post the endemic2. While one may argue that these events can’t be extrapolated to other nations, it is only wise to take the worst-case scenario and build an antifragile action plan.

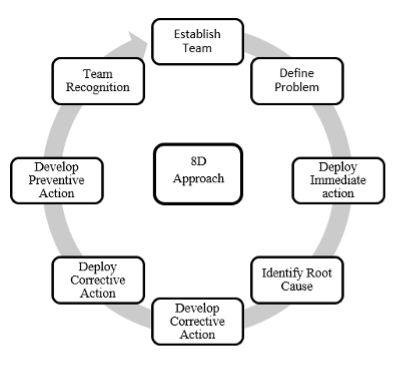

Popularly called the Eight Disciplines to problem-solving or 8D approach3, it started in the shop floors of Ford and extended to ship operations. Shown in Fig-1, it covers not only the immediate action but also the corrective and preventive action to any problem. We propose building an action plan inspired by this approach to ensure that the maternal health of pregnant women and their children are not impacted by COVID-19 and its different variants. Our Framework, as an ode to its inspiration, is called the 4D Framework and is as follows,

We strongly encourage forming an empowered committee headed by the head of state or minister of health. Further, this committee must be part of each country’s pandemic doctrine. In other words, the organization, the members, and their duties must be ideally ascertained before a pandemic.

Those from developed worlds may question having the head of state head the committee, while those from developing worlds will understand its significance. The reason for having an empowered person head the committee is twofold:

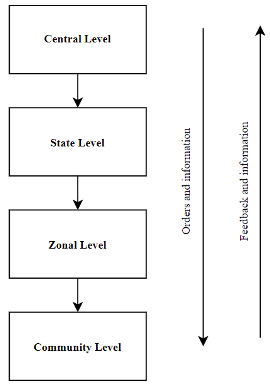

We envision a centralized structure for monitoring and a decentralized structure for decision-making and implementation. It is suggested that it be split into distinct levels: Central, State, Zonal and Community as shown in Fig-2. The members can be drawn from the government and public-health domain. An essential feature of this team is that they must also identify and include NGOs and and community leaders who have a much higher reach to the community, as evidenced in much successful public health initiatives4. Community leaders are essentially trusted members of the society and can include community health workers, religious leaders, and other individuals willing to work with the government, NGOs, healthcare workers, and public health officials.

While the literature has identified mistrust and fear, constraints in the health infrastructure and poor communication as the most common problems1, cultural nuances may need to be explored. NGOs and their volunteers and community health workers will prove invaluable in doing so. Once the problems are found, the empowered team can formulate the needed action plan and convey it down. By having this frequent and open communication between central leaders and grassroots operatives, the issue of poor communication can be averted.

It is important to note that the flow of care in clinics and hospitals is a constraint in the health infrastructure that can be improved and help maternal health services even, and perhaps especially, during epidemics and pandemics. Telehealth, phone calls, and apps can provide health information, increase communication, and replace some in-person prenatal and postnatal visits. Telehealth, phone calls, and apps are especially important during epidemics and pandemics like COVID-19 and when patients live far away from clinics and hospitals such as in rural areas and developing countries.

The immediate action plan must cater to the immediate needs of pregnant women in the pandemic. While the pandemic’s characteristics may change, needs like access to unambiguous information remain the same. A dashboard of all expectant mothers must be formulated using data available in hospitals and clinics, if not already available.

The importance of dashboards and centralizing information can be found at Santa Clara Valley Medical Centre (SCVMC). SCVMC is a public hospital and trauma center in California. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SCVMC created a Logistics Centre composed of numerous dashboards and programs such as the Flow Accelerator which allows for a panoramic view of patient flow in the hospital.5

With the creation of the Logistics Centre, there was a 30% reduction in the time from a bed request in the Emergency Department to bed assignment, which became especially helpful when the COVID-19 pandemic began5. The Flow Accelerator involves a color-coded discharge status, assigning patients as red (not ready for discharge), yellow (waiting on 1-2 consults or tests prior to discharge), and green (ready for discharge)5. By placing high importance on what’s needed to discharge the yellow color-coded patients, the Flow Accelerator has increased discharge orders before twelve noon from 15% to 40% as well as increased hospital bed turnover and thereby reduced the number of days spent in the hospital by 10-15%.

Increasing patient flow by reducing the time in between bed requests and assignments, increasing hospital bed turnover, and reducing the time spent in the hospital can thus be accomplished via dashboards which are crucial during epidemics and pandemics. The importance of timely patient flow and the impact it has on maternal health can be seen in a study examining pregnant women’s deaths in Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Paraguay, and Peru6. The researchers determined that 35% of the maternal deaths associated with COVID-19 were not admitted to intensive care.6

Information on each pregnant woman needs to be gathered as well as information about her during the delivery and postpartum. Tracking each woman’s pregnancy journey prior to delivery involves noting the term and month of their pregnancy, their prenatal visits (e.g. dates of visits, how many they’ve attended, etc.), nutrition status, anemia status (if any), blood pressure status, and other relevant medical history which includes, but is not limited to, malaria, HIV status, COVID-19 status, diabetes, cardiac diseases, weight, and the pregnant woman’s age. Knowing the patient’s weight is a standard part of taking a medical history, but it is important to mention since the aforementioned study concerning pregnant women’s deaths found that approximately 50% of the pregnant women who died were obese.6

While noting the age of patients is also a standard part of taking a medical history, it is especially important to highlight the age of younger pregnant women and closely monitor them. According to Save the Children, approximately one million additional girls in 2020 faced an increased risk of adolescent pregnancy.7 Pregnant women who are ages 10-14 have the highest risk of maternal mortality with complications during pregnancy and childbirth being higher among those ages 10-19 in contrast to those ages 20-24.8

The clinic or hospital can update the dashboard concerning the woman’s labor and delivery which not only track whether she has given birth, but also whether labor is being induced, if she will be undergoing a C-section, her blood pressure status (including possible preeclampsia and eclampsia), maternal hemorrhage (if any) and infection status (including sepsis). Fifty percent of all maternal deaths happen while a woman is in delivery or within the next 24 hours.9 Careful monitoring thus needs to continue after a woman has given birth. Infections typically happen after a woman has given birth.8 While maternal sepsis occurs in pregnant women, it is more common for puerperal sepsis to occur days after giving birth.10 Maternal hemorrhage occurs in 1% to 10% of all pregnancies and typically happens within 24 hours of delivery, though it can occur 12 weeks postpartum. 11

After being discharged from the clinic or hospital, the woman and her baby still need to be closely monitored. Infection and postpartum hemorrhage will not only be monitored, but also postnatal visits (e.g., dates of visits and how many they’ve attended, etc.), nutrition status, ease of breastfeeding (e.g., if there are severe complications then formula may need to be given to the baby), and mental health including postpartum depression. A dashboard can also be made for the baby, which, among other measures, tracks if the baby has a preterm birth, respiratory problems or other complications, has jaundice, low birth weight, needs formula, etc.

Furthermore, dedicated text message bursts and targeted public addresses in television and radio by the head of state must be part of the immediate action to inform expected mothers as well as those who gave birth. A dedicated free helpline can complement this to dispense information. Further, distribution of earmarked Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for pregnant women shall be conducted. To prevent the misappropriation of such PPE, especially in patriarchal societies, the PPE may be differentiated by feminine colors.

Virtual connections not only in the form of clinical care but also education and support groups strengthen the communication between healthcare workers and patients, provide accurate and relevant information, and alleviate mistrust and fear that women feel while pregnant, during labor and delivery, and postpartum. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Michigan Medicine recreated prenatal care with both in person and virtual prenatal visits.12 An online program was also created for pregnant women to have peer mentoring support and virtual social connections.12 The importance of virtual connections is seen via pregnant women who reported more patient empowerment, increased feelings of safety while receiving healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic, higher counseling uptake, and fewer barriers in accessing healthcare services through Michigan Medicine’s online services.12

In Italy during the pandemic, the Regional Health Authorities in Tuscany promoted the development of virtual prenatal classes which easily integrated into an already existing mobile app for maternal health called hAPPyMamma.13 The researchers noted that in addition to providing some maternal care that might not have otherwise been received during the pandemic, online virtual prenatal classes could potentially be an equitable and effective method to involve groups of immigrants who may face more challenges with typical in person prenatal classes.13

In India, the voice call service mMitra aids pregnant women in low resource urban and rural areas. The pre-recorded voice mails provide healthcare information specific to each woman’s pregnancy journey and her child’s development postpartum in the local language.14 When the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, additional pandemic information was also sent to pregnant women. In response to the pandemic, a Virtual Mentor Mother Platform (VMMP) was created to aid mothers2mothers (m2m) which works in various countries in Africa.14 The organization m2m and VMMP increased the distribution of health information to expecting mothers which included information about HIV, COVID-19, chronic disease management, maternal health, and child health. During the pandemic, 65% of m2m clients with HIV had a viral test load which is in contrast to the 60% prior to the pandemic.14 Furthermore, 85% of m2m clients with HIV obtained their antiretroviral therapy during the pandemic with a 97% adherence rate to their antiretroviral therapy in contrast to the 83% prior to the pandemic.14

Mobile clinics can also be established to improve maternal health and reach mothers who lack information and health services. During the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2021 through October 2021, Doctors Without Borders treated 37,517 patients with mobile health clinics in Brazil, specifically in Pacaraima and Boa Vista.15 These mobile health clinics provided medical, reproductive, sexual, and mental health services and were also key to providing health services to Venezuelan migrants and asylum seekers with over 3,000 homeless people in Pacaraima and about 2,000 homeless people in Boa Vista waiting for the clearance of their legal status.15

Preventive action is the most critical and needs to be done in peacetime. A live dashboard of data can be made as preventive action instead of immediate action and can be kept live by automating it. Furthermore, the development, procurement and distribution of point-of-care devices must be implemented16. This ensures that health services, especially testing services, are accessible even during quarantine. Also, a checklist may be formulated to ensure that all action is taken without prejudice as part of preventive action.

One of the most striking examples of preventative care started in the 1970s during which Costa Rica determined that the largest source of lost years of life involved maternal and child mortality.17 Under the direction of public health units, pregnant women received prenatal care and gave birth in hospitals.17 Costa Rica also improved primary care clinics who helped sick children and launched vaccination and sanitation campaigns as well as nutrition programs to decrease underweight births and food shortages. The combination of these changes resulted in 7% of children dying before their first birthday in 1970 to 2% in 1980. Maternal deaths decreased 80% from 1970 to 1980.17

A pandemic or an endemic transcends borders set by humans and makes no differentiation between people based on nationalities. As part of the 4D Framework, it’s encouraged to share the action plan with other countries to synergize efforts and get an opportunity to learn from each other. This improves their preparedness and strategy and can also improve relationships between nations.

Success sharing strategies can include writing formal or informal articles via submitting the action plan and case studies to peer reviewed journals or newspapers. White papers or blogs can also be written. Interviews, podcasts or the employment of social media to more widely disseminate the articles, white papers or blogs as well as upload videos describing the action plan will also help other countries learn about other action plans. Engaging with organizations such as nonprofits, NGOs, and governmental organizations are also important to successfully share strategies with others.

Interestingly, this framework can be applicable to other pandemics or endemics like Ebola as well. Further, it is applicable to both the developed and developing world. The beauty of our plan is the direct metrics that can be used. Our plan’s efficacy can be measured by the number of institutional deliveries and the number of women receiving minimum specified antenatal care visits. Further, the number of calls to the helpline and the number of point-of-care tests ordered can serve as indirect metrics.

A framework essentially provides its users with a linear way of solving an otherwise complex problem, and the 4D Framework is no different. A framework essentially provides its users with a linear way of solving an otherwise complex problem, and the 4D Framework is no different. The recent lockdown of Shanghai in March 2022 shows that the COVID pandemic is not yet over, and concerns still remain at large. Suppose another wave or perhaps another pandemic hit a big nation and had they adopted the 4D Framework, the following would be their approach.

Before the next wave hit the nation, they would have already built a team with the right people. Not only will the team have a head office with regional outposts, but they would also have an accurate job description for all involved. The head office will play the role of command-and-control center and shall have all the means of communications, as well as the ability to share resources with its field units. The team would have already designed a Standard Operating Procedure, and this would mean that they would have done scenario planning to prepare for such an emergency. Each team member will know the team’s expectations and whom to report to. Furthermore, and most importantly, an official of high decision-making power would lead the whole operation.

The reasons for dropping maternal health cannot be immediately evident in a big country with different racial, religious and ethnic identities. It is out here that they need people connected to the grass-root level. While NGOs and community health workers will definitely play a significant role, the importance of religious leaders cannot be overshadowed. In many parts of the world, the people trust their religious leaders more than the government and listen to them willingly. This was evident in countries like India, where the head of a minority community appealed18 to the community as a whole to get vaccinated, considering that they suffered from low immunization levels19. Similarly, they’ll prove helpful in case of religious or cultural barriers related to maternal health and thus should not be overlooked. This information will be crucial for the head office to develop an action plan.

While the head office can publish a base action plan, the onus of implementation would fall on the regional centers. This is because they would better understand local constraints and can modify the action plan accordingly. For example, the base action plan may dictate that community health workers must check the pregnant women in their houses thrice a week. However, if they live in a mountainous region, where travel is restricted by weather and avalanches, this plan may not work. The regional centers may have to modify such action plans and deploy them locally.

An innovative solution to handle the health of pregnant women must be shared. This part of the framework is from proven use cases where technology and innovation have been made open source for the benefit of humanity. One example from the automobile industry was the three-point safety seat belt made open source by Volvo. A more recent example from the pandemic was the Indian government making its vaccine handling software CoWIN (Covid Vaccine Intelligence Network) open source. It can handle 25 million doses a day and received interest from many countries.20

It only takes a day to produce a mass-market car and around six months to make a Rolls-Royce21, but an expecting mother would have spent nine months in anticipation and care to deliver a bundle of joy. Isn’t it upon us as a society to pandemic-proof our expecting mothers?

Figure 1 8D Approach to problem solving 3

Figure 2 Structure of the team

Nicolle Ma has a background in healthcare and clinical research involving patients with depression, schizophrenia, breast cancer, and gastrointestinal conditions and diseases.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.