Hynes M. The absolute necessity of plant-based diets for the health of the earth and her inhabitants. HPHR. 2021;41. 10.54111/0001/OO7

Plant-based diets have been emphasized as healthy for decades. When I was very young, I heard a writer, Frances Moore Lappé, discuss her book, Diet for a Small Planet (Lappé, 1971). This was the first major book to note the environmental impact of meat production as wasteful and a contributor to global food scarcity. We should have listened more closely to her, particularly those in the West. The Western diet, laden with processed foods, is helping to kill the inhabitants and the planet. Most impacted are those affected by poverty. New studies indicate a plant-based diet (PBD) has incredible health benefits.

Malnutrition is an umbrella term. The World Health Organization recognizes malnutrition under nutrition (wasting, stunting, being underweight), hidden hunger (diseases due to inadequate vitamins or minerals) and obesity (due to limited access to healthy foods and a diet-related non-communicable diseases) (WHO, 2020).

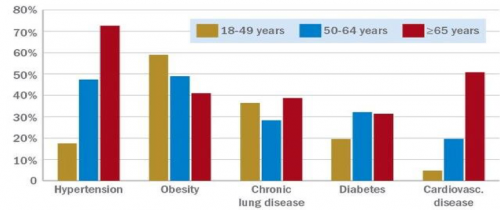

Today, malnutrition tends to be presented as overweight and obesity, especially among the poor and racial and ethnic minorities. Overweight is defined as a person with a body mass index (BMI) over 25 kg/m2; obesity id defined as having a BMI over 30kg/m2 and severe obesity over 40kg/m2. Almost 2 billion people are overweight or obese, and live in countries where this kills more people than being underweight (WHO, 2021). Much of this obesity is associated with elevated risk of disease and mortality related to how the excess fat is stored. Visceral adiposity or obesity (VAT) (adipose tissue around the waist and internal organs), is emerging as a risk factor for cardiac, diabetes and other comorbid diseases related to obesity. The adipose tissue in VAT increases production of several hormones, including pro-inflammatory adipokines, which may explain the links between visceral obesity and metabolic syndrome and diabetes. In addition, having excess visceral fat is associated with medical disorders such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, chronic kidney and several malignancies, including prostate, breast, and colorectal cancers (Shuster, Patlas, Pinthus, & Mourtzakis, 2012).

Women, infants, children, and adolescents are at particular risk of malnutrition. Good nutrition begins in the womb. Optimizing nutrition early in life—including the 1000 days from conception to a child’s second birthday—has long-term benefits (Schwarzenberg & Georgieff, 2018). Inadequate micronutrients and poor diets can lead to poor outcomes, such as premature birth and high infant mortality (Komlos, 2015). Obesity in childhood is often predictive of obesity in adolescence and adulthood (Llewellyn, Simmonds, Owen, & Woolacott, 2016).

A big factor in our obesity crisis is that our current intake of ultra-processed foods(UPFs ) is not only contributing to obesity and its related diseases: it is also a contributing factor to climate change. PBDs should be considered a viable option for patients who are interested in losing weight and improving dietary quality consistent with chronic disease prevention and treatment. Using a PBD would be transformative in helping to lessen the effects of this crisis.

The main reason for the increase in the prevalence of people who are overweight and have obesity in the United States is the inability of food systems to deliver affordable healthy diets. A major preventable risk factor contributing to the burden of disease worldwide is a poor diet, including inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption, and affordability worldwide is an issue (Lee, 2016). Minimally processed (whole) foods are more difficult to access and can be expensive and less convenient.

UPF foods are unhealthy. They are usually made usually from five or more synthetic food compounds per product and usually do not contain whole foods. UPFs commonly contain artificial substances such as inorganic phosphates, artificial sweeteners, dyes, and other additives, which increase shelf life and flavor (Lane et al., 2021). These foods are more likely to be high in sodium, phosphates, sugar, and saturated fats, which are associated with chronic diseases, such as hot dogs, potato chips and sugared beverages. UPFs account for more than 50% of the calories in the United States (Ostfeld & Allen, 2021). They tend to be much cheaper that whole foods, and their use has greatly increased over the last decade or so.

Studies have shown negative effects of UPFs. In a large, observational prospective study, higher consumption of UPFs was associated with cardiovascular risks (Srour et al., 2019). The consumption of red meats, but in particular, processed meats, have also been associated with increased mortality (Yang et al., 2015). Processed meats include any meat that is smoked, barbecued or cured and not in its original form (López-Hernández et al., 2020). This includes bacon, ham, sausages, corned beef, jerky, and canned meats. Meat processing includes all the processes that change fresh meat except cutting, grinding or mixing. UPFs and sugared drink products consumption has been associated with obesity and its-related comorbidities (Konieczna et al., 2021). In a recent study, a higher consumption of UPFs was associated with greater VAT. Red and processed meats are also associated with VAT, leading to comorbid diseases already mentioned, and high fiber foods, such as fruits, are associated with decreased visceral obesity.

To illustrate the above concepts, a recent landmark study at the National Institute of Health (NIH)showed that those who ate processed food gained weight and ate more than whose who ate minimally processed food. Researchers admitted 20 healthy adult volunteers, 10 men and 10 women, to the NIH Clinical Center.. For one continuous month, and in random order for two weeks on each diet, they provided them with meals made up of ultra-processed foods or meals of minimally processed foods. The ultra-processed and unprocessed meals had the same amounts of calories, sugars, fiber, fat, and carbohydrates, and participants could eat as much or as little as they wanted.

For example, an ultra-processed breakfast might consist of a bagel with cream cheese and turkey bacon, while the unprocessed breakfast was oatmeal with bananas, walnuts, and skim milk. On the ultra-processed diet, people ate about 500 calories more per day and they ate faster, gained weight (2 pounds), whereas they lost weight (2 pounds) on the unprocessed diet. Interestingly, those on the low processed diet had higher levels of an appetite-suppressing hormone called PYY, which is secreted by the gut, and lower levels of ghrelin, a hunger hormone, which might explain why they ate fewer calories.

In the above experiment at NIH, the weekly cost for ingredients to prepare 2,000 kcal/day of ultra-processed meals was estimated to be $106 versus $151 for the unprocessed meals using a large supermarket chain. Many with a lower income prefer UPF, in large part because of their cost (Drewnowski, 2007). To conclude, UPFs cause weight gain, are associated with visceral fat and obesity and are about one-third cheaper to buy than non-processed foods.

Where do the impoverished get the UPFs? In addition to grocery stores, they also buy food at local dollar stores and convenience stores, which are generally cheaper and have mostly highly processed food. Most of these stores take Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Cards. (formerly food stamps). Our government has promoted these purchases as well. For example, the number of dollar stores in North Carolina authorized to accept SNAP benefits increased from 0 stores in 2000 to 1,123 stores in 2014. In a study, some of the stores had healthy items; however, none of the stores sold fresh fruits and vegetables (Racine, Batada, Solomon, & Story, 2016). At dollar stores in Minnesota, snacks bought averaged 1300 calories, and sugared beverages were the most common purchase (Caspi, Pelletier, Harnack, Erickson, & Laska, 2016). In addition, most healthy foods were perceived by store managers to have the least profitability at these types of stores (Caspi et al., 2016). Hence, cheaper stores draw customers to more unhealthy foods.

The poor also go to food pantries, which are often run by religious groups with mostly donated foods. Food pantries are crisis interventions for chronic problems. Although they are there to help, only 22% of food banks have policies on sugared beverages (Fisher & Jayaraman, 2017), and most do not note whether the food is actually healthy, and much of it is UPFs due to problems with food storage such as refrigeration. Low-income is the most important reason for going to a food bank with all participants reporting a constant struggle to afford food. “Shopping pantries, where the patients pick out their foods are much better than giving out boxes of food that do not take food preferences into account (Fisher & Jayaraman, 2017). In summary, food pantries do provide food, but there is minimal regulation on whether that food is healthy or even preferred by patients.

Much has been written about food deserts, and it will not be addressed here. The so-called food swamps or increased density of fast food restaurants in poor areas, which sell ultra-processed foods, was more a predictor of obesity than food deserts (Cooksey-Stowers, Schwartz, & Brownell, 2017).

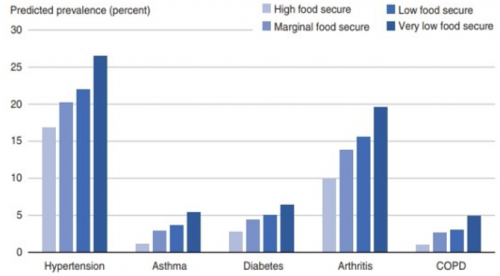

Food security status is more strongly predictive of chronic illness in some cases even than income, due to weight gain and poor diet. For example, one-half of Latino and African American children will develop DM born after 2000 vs. one-third of Whites, mostly due to added sugar. Interestingly, the Southern diet alone, rich in processed meats and sugar-sweetened beverages was the largest mediator in the racial disparity in hypertension, accounting for one-half the excess risk in African American men and almost a third of the women (Howard et al., 2018).

There is a 40 percent increase in overall prevalence of chronic disease for those with food insecurity, which is associated with a higher probability of obesity, hypertension, coronary heart disease hepatitis, stroke, cancer, asthma, diabetes, arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease kidney disease (USDA, 2017). Interestingly, those who have had hospital admission for COVID often have these comorbidities as well.

A recent study showed that plant-based diets (PBDs) containing higher amounts of healthy foods, such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, oils, tea, and coffee are associated with lower cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk and disease (Satija & Hu, 2018). The Mediterranean diet (rich in plants, fish, olive oil, nuts and seeds), the DASH diet (rich in plants, but allows low-fat dairy and lean meats and fish),vegan (no animal products) and vegetarian (plants and dairy) diets are all examples of PBDs that have health benefits (Benson & Hayes, 2020). All of the diets supply all macronutrients, minerals and vitamins needed for health with the exception of vegan diets, which require B12 supplementation (found only in animal products). Patients can become confused as to what they are supposed to do, as not all plants are healthy (e.g., French fries). For purposes of this article, plant-based diets are referring to all diets that encourage more intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds and whole grains. They generally discourage processed foods that are higher in sodium and saturated fats such as fried potatoes, juices and beverages that are high in added sugar, as they are linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Arnett et al., 2019). What you eat makes a big difference in all aspects of health.

In addition, individuals consuming PBDs tend to have lower BMI than those consuming non-PBDs, and current literature shows it is also effective for weight loss (Turner-McGrievy, Mandes, & Crimarco, 2017). PBDs should be considered a viable option for patients who are interested in losing weight and improving dietary quality consistent with chronic disease prevention and treatment.

Plant-based diets are gaining more medical support over the last decade. They are associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease when compared to those not on a similar diet, as high fiber foods help with cholesterol and sugar control. In a systematic review of the Seventh Day Adventist cohorts in California, vegetarians were less likely than their omnivore cohorts to have elevated body mass index (BMI), hypertension, or Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)— significant risk factors for development of CVD. The American Heart Association’s new 2019 guidelines support PBDs as a viable treatment option for prevention of cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease and hypertension.

A recent article in Lancet recommended a dramatic reduction in red meat consumption for people who eat it regularly, such as Americans and Canadians, who eat more than six times the recommended amount of red meat (da Silva, 2019). The diet they recommended was half a plate of fruits, vegetables, and nuts. The other half is whole grains, plant proteins (beans, lentils, pulses), unsaturated plant oils, modest amounts of meat and dairy, and some added sugars and starchy vegetables. The diet is quite flexible and allows for adaptation to dietary needs, personal preferences, and cultural traditions. Vegetarian and vegan diets are two healthy options within the planet health diet but are personal choices. Canada has eliminated the dairy portion to its recommended healthy plate, while the dairy portion is still supported in the U.S. The U.S. requirements of having three servings a day do not appear to be justified. However, if diet quality is low, especially for children in low-income environments, dairy foods can improve nutrition, whereas if diet quality is high, increased intake is unlikely to provide substantial benefits, and harm is possible (Willett & Ludwig, 2020). There are many varieties to the PBDs that can fit into different lifestyles.

Therefore, a wide spectrum of plant-based diets can be nutritionally adequate and confer cardiovascular benefits. Rather than debating with patients about which is the healthiest diet, the focus should be on improving overall diet and increasing eating healthy plants with patient preferences and culture in mind. A brochure with a list and pictures of the best foods would help. A registered dietician can help immensely with this transition, as well. For example, those patients with chronic kidney disease who worked with a dietician had a 15% decrease in mortality and decreased renal disease progression (Steiber, 2014). However, barriers to care, such as not knowing it was a Medicare benefit in renal disease, or providers not being reimbursed have led to small numbers seeing a dietician before dialysis (Jimenez et al., 2021). In fact, PBDs, especially vegan diets, are now in the guidelines for care of the patient with renal disease, and a small study showed how a vegan diet could delay hemodialysis for a year.

In the words of Michael Pollan, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants” (Macduffee, K., 2013).

Consumption of healthy diets presents major opportunities for reducing Green House Gas (GHG) emissions from food systems and improving overall health. Up to 37% of total GHG can be from the food system. These are from farming, storage, transport, packaging, processing and retail, so an emphasis on having local food would help the planet. However, most of the GHG come from raising livestock, mostly beef. Much of this is due to methane burped by cows, growing feed, and clearing land for grazing and feed crops (Gustin, 2019).

For instance, if the world’s average diet became flexitarian (red meat consumption limited to one serving per week and white meat to half a portion per day) by 2050, the GHG emissions of the agricultural sector would be reduced by around 50%. If everyone in the country did go vegetarian, cutting meat out completely and replacing it with plant proteins of the same nutritional value, we would save 330 million metric tons of GHG emissions per year. By cutting emissions of greenhouse gases we can lessen the risks of dangerous climate change.

In the words of Raj Patel, a healthy food activist, “value meals” should not be fast food but made of produce that is local, sustainable and shared by everyone (Patel, 2010). Examples of these diets are those that are high in coarse grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds, low in energy-intensive animal-sourced and discretionary foods (such as sugary beverages).

Public health professionals think of food as medicine and food policy as health policy and become more active in their communities. They can encourage patients to support local farmers and community gardens. Local means produce does not have to travel as far to reach your table, thus decreasing GHG emissions, and it can be picked when it is ready to eat. “Fruits and vegetables are often the most attractive and health-promoting when harvested at the peak of maturity,” says Diane M. Barrett, Ph.D. (Consumer Reports on Health, 2015). (She is a specialist in the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of California, Davis). But “local” is not a regulated term; each market can have its own definition. Therefore, patrons must ask if their produce is local and support those markets.

Public health experts, health care providers and environmental scientists need to come together and align as to what is best for our patients and the earth we all live in. Environmental experts advise two ways we all can lower GHG: We need to substitute animal-source foods and reduce household waste (Stevanović et al., 2017). Another article in Nature said that in order to feed the 10 billion people in 2050, we need to not only adopt plant-based foods, but also start adopting new farming technologies (Eshel, Stainier, Shepon, & Swaminathan, 2019). All health care professionals need to become more politically active and push for support for more plant-based diets for our patients and the earth. Food Policy, therefore, is Health Policy.

In addition, the government could be more pro-active in promoting PBDs. The United States Government should be involved in helping enforce sound nutritional policies. Children should be taught nutrition in health programs in schools. The government currently spends 38 billion dollars supporting meat and dairy farming, but only less than 1% of that, (17 million) on plant subsidies (Sewell, 2020). SNAP and food programs should promote plant -based diets and not allow dollar and convenience stores to take SNAP dollars.

Those who have studied ultra processed diets and its effects on cardiovascular disease, say “Reducing the consumption of ultra-processed foods requires additional substantial collaborative policy reform, implementation of widespread educational programs, marketing and labeling changes (such as using NOVA categories to label foods), and improved access to affordable less-processed foods, among other initiatives. Ultimately, the goal should be to make the unhealthy choice the hard choice and the healthy choice the easy choice” (Ostfeld & Allen, 2021). This statement is backed at least by one study, which showed that when fast food prices were higher, fiber consumption increased and BMI decreased (Beydoun, Powell, & Wang, 2008).

In addition, another option is to tax unhealthy foods, such as sodas. This has worked to reduce consumption in Mexico. Preliminary results from a study by found there was an average 6 percent decrease in soda sales in the first year that intensified to 12 percent the following year and down as much as 17 percent for the lowest-income Mexicans (Margot, 2017). What still is not known is whether health has improved because of this. Similar taxes have been initiated in several U.S. states.

In Berkeley, California, a similar tax resulted in a decrease of 50% of soda, and an increase in water, particularly the poor. What did they do with the money (about 5 million) made from taxing the soda? They put much of it into local farmers’ market. Ajura Smith from the Berkeley non-profit Healthy Black Families, which received $245,874, said the tax has helped mobilize her group to give tours of the Berkeley Farmers Market and offer classes in healthy meal preparation and shopping. “We talk about obesity and diabetes, and really make it real,” she said. Among the group’s programs, it offers a “$10 shopping challenge,” showing residents how to buy a meal for a family of four on a $10 budget (Hicks, 2019). This is an example of how our government could improve people’s health.

The government, setting higher standards for plant-based diets, should be involved in helping with encouraging plant-based diets and thus climate change by supporting more plant agriculture and decreasing meat and particularly cattle farming. We also need to care for those caring for us: a healthy living wage for those involved with our food from picking to grocery stores should be standard. COVID-19 taught us how important our food workers are.

In summary, we all need to support food policies that are healthy and climate-friendly, (which would be a win/win situation) and we need to do it now! The health of ourselves and our planet depend on it.

Arnett, D. K., Blumenthal, R. S., Albert, M. A., Buroker, A. B., Goldberger, Z. D., Hahn, E. J. (2019). 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 74(10), e177-e232.

Benson, G., & Hayes, J. (2020). An update on the Mediterranean, vegetarian, and DASH eating patterns in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum; Diabetes Spectr, 33(2), 125-132.

Beydoun, M. A., Powell, L. M., & Wang, Y. (2008). The association of fast food, fruit and vegetable prices with dietary intakes among US adults: Is there modification by family income? Social Science & Medicine (1982); Soc Sci Med, 66(11), 2218-2229.

Caspi, C. E., Pelletier, J. E., Harnack, L., Erickson, D. J., & Laska, M. N. (2016). Differences in healthy food supply and stocking practices between small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Public Health Nutrition; Public Health Nutr, 19(3), 540-547.

Consumer Reports on Health. (2015). Give your health a produce boost; easy ways to reap the most benefits from the fruits and vegetables that you eat.

Cooksey-Stowers, K., Schwartz, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. (2017). Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the united states. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; Int J Environ Res Public Health, 14(11), 1366.

da Silva, J. G. (2019). Transforming food systems for better health. The Lancet (British Edition); Lancet, 393(10173), e30-e31.

Drewnowski, A. (2007). The real contribution of added sugars and fats to obesity. Epidemiologic Reviews, 29, 160-171.

Eshel, G., Stainier, P., Shepon, A., & Swaminathan, A. (2019). Environmentally optimal, nutritionally sound, protein and energy conserving plant based alternatives to U.S. meat. Scientific Reports; Sci Rep, 9(1), 10345-11.

Fisher, A., & Jayaraman, S. (2017). Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance Between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Gustin, G. (2019). As beef comes under fire for climate change, the industry fights back. Civil Eats. Retrieved from https://civileats.com/2019/11/08/as-beef-comes-under-fire-for-climate-impacts-the-industry-fights-back/.

Hicks, T. (2019). Where are the millions from berkeley’s soda tax going? lots of places. Berkeleyside. Retrieved from https://www.berkeleyside.org/2019/02/07/where-are-the-millions-from-berkeleys-soda-tax-going-lots-of-places

Howard, G., Cushman, M., Moy, C. S., Oparil, S., Muntner, P., Lackland, D. T., . . . Howard, V. J. (2018). Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in black compared with white US adults. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association; JAMA, 320(13), 1338-1348.

Jimenez, E. Y., Kelley, K., Schofield, M., Brommage, D., Steiber, A., Abram, J. K., & Kramer, H. (2021). Medical nutrition therapy access in CKD: A cross-sectional survey of patients and providers. Kidney Medicine; Kidney Med, 3(1), 31-41.e1.

Komlos, J. (2015). In america inequality begins in the womb. PBS News Hour. Retrieved from: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/making-sense/america-inequality-begins-womb#:~:text=The%20Nobel%20Prize%20winning%20economist,of%20inequality%20in%20America%20today..

Konieczna, J., Morey, M., Abete, I., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Ruiz-Canela, M., Vioque, J., . . . Romaguera, D. (2021). Contribution of ultra-processed foods in visceral fat deposition and other adiposity indicators: Prospective analysis nested in the PREDIMED-plus trial. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland); Clin Nutr, 40(6), 4290-4300.

Lane, M. M., Davis, J. A., Beattie, S., Gómez‐Donoso, C., Loughman, A., O’Neil, A., . . . Rocks, T. (2021). Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of 43 observational studies. Obesity Reviews; Obes Rev, 22(3), e13146-n/a.

Lappé, F. M. (1971). Diet for a Small Planet. New York: Ballantine Books.

Le, L. T., & Sabaté, J. (2014). Beyond meatless, the health effects of vegan diets: Findings from the adventist cohorts. Nutrients; Nutrients, 6(6), 2131-2147.

Lee, A. (2016). Affordability of fruits and vegetables and dietary quality worldwide. The Lancet Global Health; Lancet Glob Health, 4(10), e664-e665.

Llewellyn, A., Simmonds, M., Owen, C. G., & Woolacott, N. (2016). Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews; Obes Rev, 17(1), 56-67.

López-Hernández, L., Pérez-Ros, P., Fargueta, M., Elvira, L., López-Soler, J., & Pablos, A. (2020). Identifying predictors of the visceral fat index in the obese and overweight population to manage obesity: A randomized intervention study. Obesity Facts; Obes Facts, 13(3), 403-414.

Macduffee, K. Eat food – not too much – mostly plants. (2013). Caledon Enterprise. Retrieved from: https://www.toronto.com/opinion-story/3917724-eat-food-not-too-much-mostly-plants/.

Margot, S. (2017). Sales fall again in mexico’s second year of taxing soda. New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/upshot/soda-sales-fall-further-in-mexicos-second-year-of-taxing-them.html.

National Institutes of Health. NIH study finds heavily processed foods cause overeating and weight gain. (2019). Washington, DC: Federal Information & News Dispatch, LLC. Retrieved from: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-study-finds-heavily-processed-foods-cause-overeating-weight-gain#:~:text=People%20eating%20ultra%2Dprocessed%20foods,National%20Institutes%20of%20Health%20study.

Ostfeld, R. J., & Allen, K. E. (2021). Ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular disease: Where do we go from here? Journal of the American College of Cardiology; J Am Coll Cardiol, 77(12), 1532-1534.

Patel, R. (Producer), & Patel, R. (Director). (2010). The value of nothing. [Video/DVD]

Racine, E. F., Batada, A., Solomon, C. A., & Story, M. (2016). Availability of foods and beverages in supplemental nutrition assistance Program−Authorized dollar stores in a region of north carolina. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; J Acad Nutr Diet, 116(10), 1613-1620.

Satija, A., & Hu, F. B. (2018). Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine; Trends Cardiovasc Med, 28(7), 437-441.

Schwarzenberg, S. J., & Georgieff, M. K. (2018). Advocacy for improving nutrition in the first 1000 days to support childhood development and adult health. Pediatrics (Evanston); Pediatrics, 141(2), e20173716.

Sewell, C. (2020). Removing the meat subsidy: Our cognitive dissonance around animal agriculture. Journal of International Affairs (New York), 73(1), 307-318.

Shuster, A., Patlas, M., Pinthus, J. H., & Mourtzakis, M. (2012). The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: A critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. British Journal of Radiology; Br J Radiol, 85(1009), 1-10.

Srour, B., Fezeu, L. K., Kesse-Guyot, E., Allès, B., Méjean, C., Andrianasolo, R. M., . . . Touvier, M. (2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-santé). The BMJ; BMJ, 365(365), l1451.

Steiber, A. L. (2014). Chronic kidney disease: Considerations for nutrition interventions. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 38(4), 418-426.

Stevanović, M., Popp, A., Bodirsky, B. L., Humpenöder, F., Müller, C., Weindl, I., . . . Wang, X. (2017). Mitigation strategies for greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and land-use change: Consequences for food prices. Environmental Science & Technology; Environ.Sci.Technol, 51(1), 365-374.

Turner-McGrievy, G., Mandes, T., & Crimarco, A. (2017). A plant-based diet for overweight and obesity prevention and treatment. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology : JGC; Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 14(5), 369-374.

WHO (2020). Fact sheet: Malnutrition. Retrieved from https://www.WHO/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition

WHO (2021). Obesity and overweight. Retrieved from https://www.WHO/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

USDA (2017) Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Health Among Working-Age Adults. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/pubid=84466

Willett, W. C., & Ludwig, D. S. (2020). Milk and health. The New England Journal of Medicine; N Engl J Med, 382(7), 644-654.

Yang, L., Dong, J., Jiang, S., Shi, W., Xu, X., Huang, H., . . . Liu, H. (2015). Red and processed meat consumption increases risk for non-hodgkin lymphoma: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore); Medicine (Baltimore), 94(45), e1729.

Dr. Marijane Hynes, MD, ABOM is a board certified in General Internal Medicine and a diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine. She joined the faculty of George Washington University in 1998 and has been Director of the Weight Management Clinic since 2009. She has taught at George Washington University Medical School since 1998, including lectures on obesity and weight management. She oversees a multidisciplinary team, including 4 certified ABOM physicians, a psychiatrist, and a registered dietician, who care for patients diagnosed with obesity. She also developed a model of care for patients with obesity and wrote guidelines. Her clinical areas of interest include comorbidities of obesity, both physiologic and psychologic; visceral fat and its association with disease state; weight management; and patient weight loss. She has authored several articles on nutrition, obesity and how nutrition relates to co-morbid conditions such as atrial fibrillation.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.