Nhede N, Catraio A. Neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and under-five mortality rates in the provinces of Zimbabwe: a geostatistical and spatial analysis of public health policy provisions. HPHR. 2021;34.

DOI:10.54111/0001/HH11

The aim of this research is to present a disaggregated geostatistical analysis of the subnational provincial trends of child mortality variation in Zimbabwe from a child health policy perspective. Soon after gaining independence in 1980, the government embarked on efforts towards promoting equitable health care, namely through the provision of primary health care. Government intervention programmes brought hope and promise, but achieving equity in primary health care coverage was hindered by previous existing disparities in maternal health care disproportionately concentrated in urban settings to the detriment of rural communities. The article highlights policies and programs adopted by the government during the Millennium Development Goals period between 1990-2015 as a response to the inequities that characterised the country’s maternal health care. A longitudinal comparative method for spatial variation on child mortality rates across provinces is developed based on geostatistical analysis. Cross-sectional and time-series data was extracted from the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Health Observatory data repository, Demographic Health Surveys reports, and previous academic and technical publications. Results suggest that although health care policy was uniform across provinces, not all provinces received the same antenatal and perinatal services. Accordingly, provincial rates of child mortality growth between 1994 and 2015 varied significantly. Evidence on the trends of child mortality rates and maternal health policies in Zimbabwe can be valuable for public child health policy planning, and public service delivery design both in Zimbabwe and across developing countries pursuing the Sustainable Development Agenda.

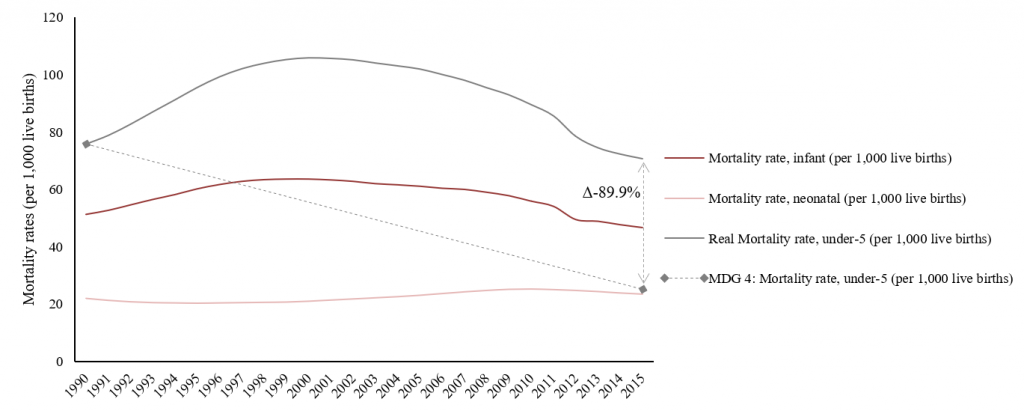

Childhood mortality rate has been a worrying factor in many developing countries. In Zimbabwe, between 1990 and 2015, neonatal (first 28 days of life) mortality increased by 6.81%, while infant (under the age of 1) and under-five (before reaching age 5) mortality decreased by -8.98%, and -6.72% (WHO, 2019). In other words, while infant and under-five mortality rates decreased at low levels during the period, a substantial increase in neonatal mortality rates was verified in the country.

Figure 1. Child Mortality Rates in Zimbabwe during the period between 1990 and 2015. Source: Developed by the authors with data from the WHO Global Health Observatory data repository.

The Millennium Development Goal 4 (MDG4) stipulates the reduction of under-five mortality rate by two-thirds at the national level during the period between 1990 and 2015. In this regard, under the adoption of the MDG4, Zimbabwe has achieved extremely limited results. The time-series trends for infant mortality rates, neonatal mortality rates, and under-five mortality rates are presented in Figure 1, accompanied by MDG4 trend estimation for the period. Notedly, the observed under-five mortality rate in Zimbabwe by 2015 achieved less than 89.9% of the preestablished MDG4. Thereby, the reduction of under-five mortality rate by -6.72% accordingly accounted for a 10.08% achievement of the MDG4 target.

Previous studies on child mortality, particularly focused on Zimbabwe, have raised different accounts on the determinants of child mortality variation. Shortly after the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980, using time-series data, Sanders and Davies (1988) demonstrated that the post-independence expansion of the health care system was associated with a wide decrease in child mortality rates in the country compared to pre-independence child mortality rates. In addition, they found that such results were independent of economic shocks.

Similarly, other authors have focused on the role played by health care provisions and overall improvements on child care attention in the decrease of child mortality rates. Relying on time-series clinical data from a Maternity Hospital in Bulawayo, Aiken (1992) stated that a significant reduction in perinatal mortality was attained by fostering antenatal, intrapartum and neonatal care at the hospital, especially when combined with family planning initiatives. Using cross-sectional aggregated data from world regions (Zupan, 2005; Boschi-Pinto, 2008), further studies supported the claim that professional care provision and planning and evaluation of child health intervention strategies had a positive correlation with the reduction of child mortality. And with a multivariate regression model based on repeated cross-sectional data from Zimbabwe, Kembo and Ginneken (2009) stressed the importance of health policy initiatives related to family planning methods to ameliorate the conditions of child health across households.

Some studies, however, have emphasized the importance of socioeconomic and living standards determinants on child mortality increase. With data from the Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey, Madzingira (1995) found evidence through a logistic regression analysis that birth weight, duration of breastfeeding, and residence were associated with lower levels of child health. Poverty indicators, related to limited access to health facilities, were found to be significant in spatial comparative analyses of urban and rural areas in Zimbabwe (Kambarami et al., 1997; Root, 1997), suggesting that areas with higher exposure to infectious diseases or epidemics (Shapiro and Lockman, 2010; Emmanuel et al., 2011), and with poor access to health facilities, tend to present higher rates of child mortality.

Furthermore, it has been observed that living standards related to maternal education have an association with child mortality. Utilizing a multivariate regression analysis with cross-sectional and time-series data from the Demographic and Health Survey program from 1986 to 1998, Rutstein (2000) argues that although there are no simple solutions to reduce child mortality, maternal education appeared to be consistently associated with child mortality rates decrease across developing countries. Grépin and Bharadwaj (2015) found similar results with a natural experiment design that tested the association of post-independence education expansion for women in Zimbabwe and the decrease of child mortality rates among their families when compared to Zimbabwean mothers that unfortunately were not educated during the pre-independence period. The mechanisms through which a mother’s education can help to reduce child mortality rates are potentially related to family planning, better income, and maternal education such as the adoption of early exclusive breastfeeding practices (Koyanagi et al., 2009). The overall association between living standards and child health care provision has been successfully supported with longitudinal data regarding other developing countries (Wagstaff, 2000).

A common caveat among previous studies has been raised by Nathoo (1991), and Kambarami et al. (1997). Notably, they point out that the lack of high-quality epidemiologic data in developing countries, and recurrent missing data attritions, may potentially threaten internal validity. Favored by a new body of updated subnational longitudinal data provided by the WHO, the aim of this research is to present a disaggregated geostatistical analysis of the subnational provincial trends of child mortality variation in Zimbabwe from a child health policy perspective during the MDG period between 1990 and 2015. Therefore, our aim is to contribute to current literature on the association of healthcare provisions and child mortality rates in contemporary Zimbabwe.

The strategy adopted in this study combines geostatistical analysis with public health policy administration to describe: a) how neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates varied across provinces in Zimbabwe during the MDG period between 1990 and 2015; and b) which policies the Zimbabwean government implemented to reduce child mortality rates in the country.

Subnational longitudinal data was gathered for our geostatistical analysis on child mortality rates from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2019) database. Collected data on child mortality rates refer to neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates of each province of Zimbabwe: Manicaland, Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland West, Matabeland North, Matabeland South, Midlands, Masvingo, Harare, and Bulawayo. During the MDG period between 1990 and 2015, data from each province was successfully collected for the years 1994, 1999, 2005, 2010, 2015. Because disaggregated data on child mortality rates are not available for all the years during the MDG period, 1994 will be used as a proxy baseline for 1990. And given that the national aggregated measure of under-five mortality rates presented in Figure 1 already stated the failure of attaining MDG4, the spatial disaggregated analysis intends to further elucidate the particular outcomes achieved by each province.

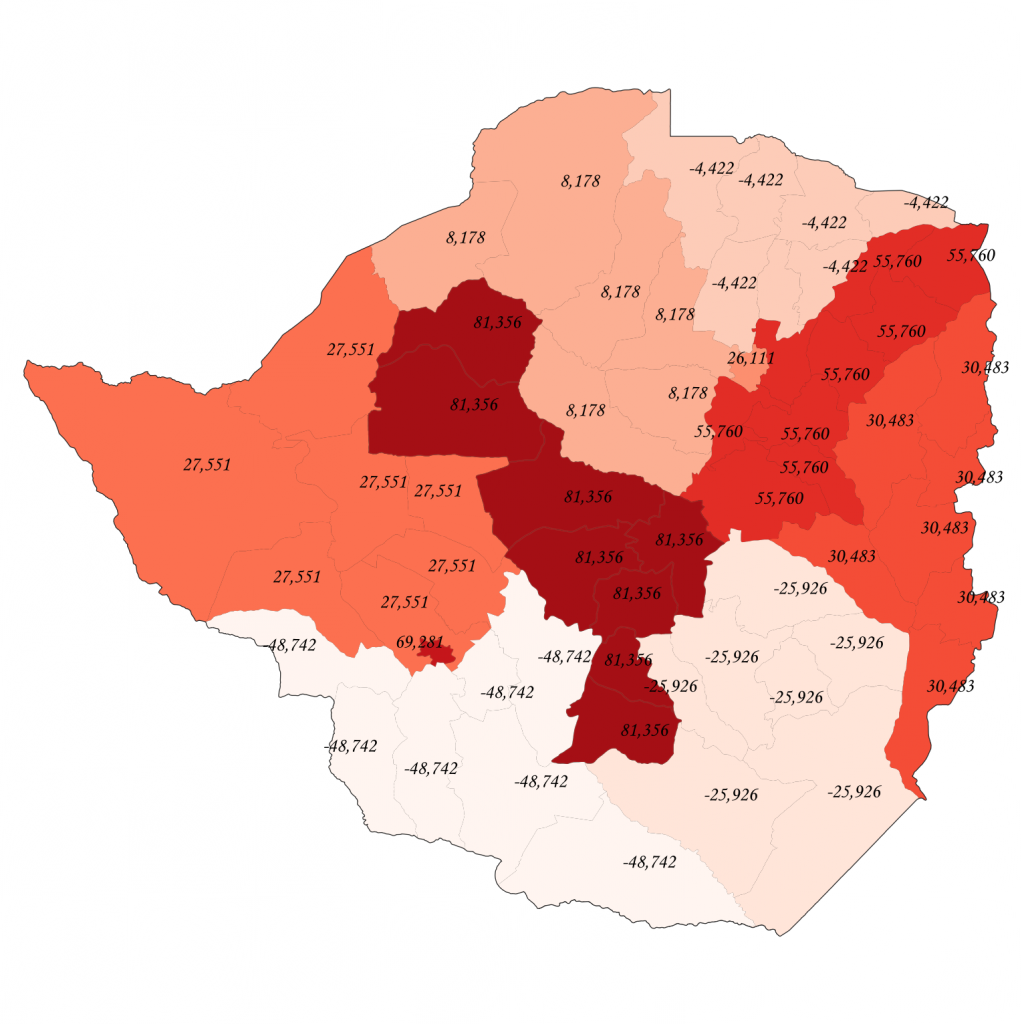

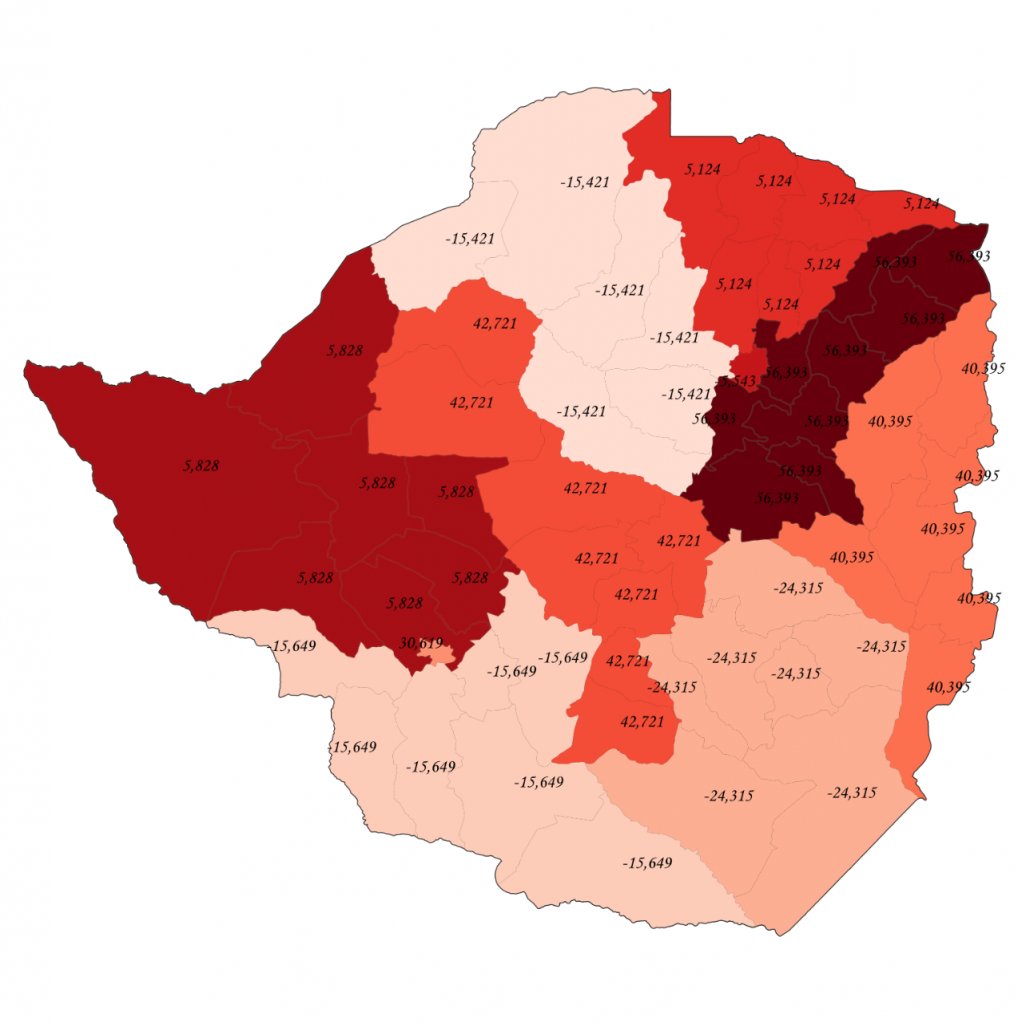

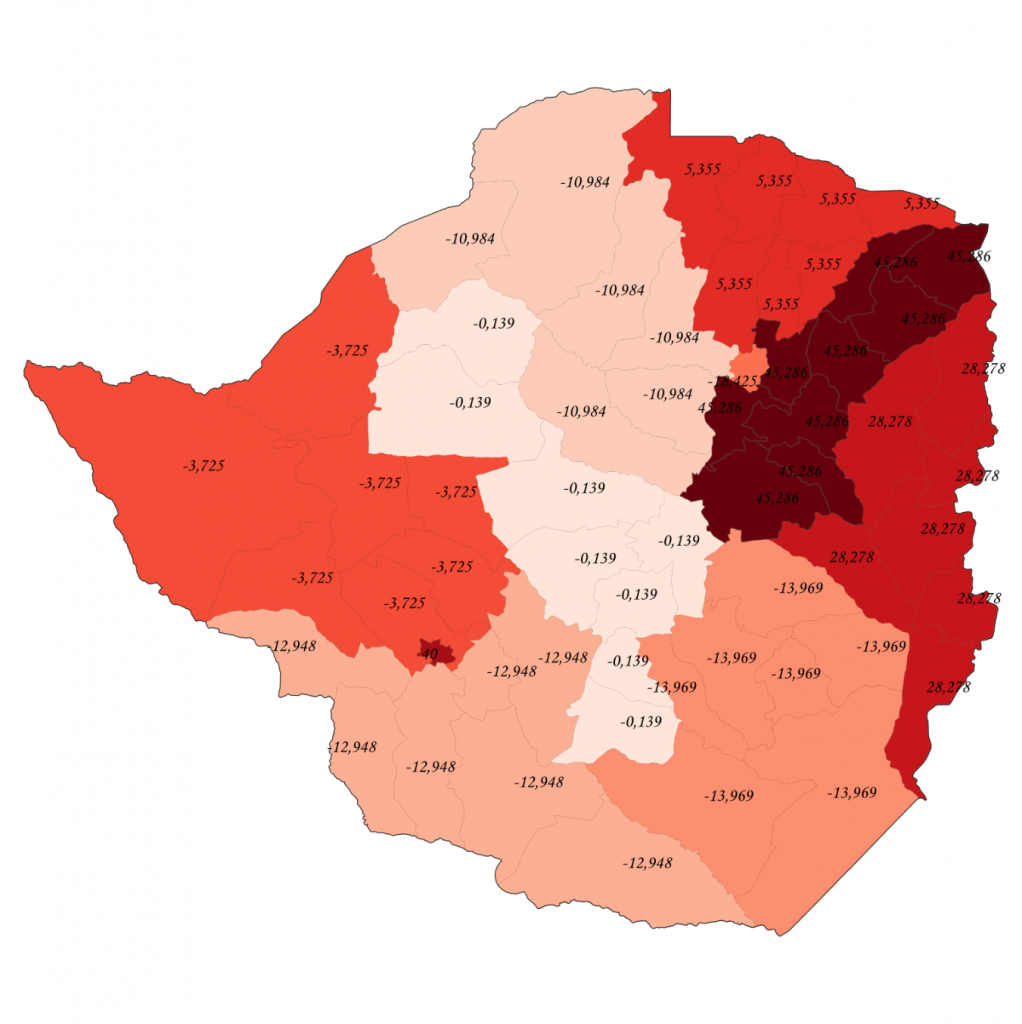

In regard to map designing, Geographic Information System was utilized to match spatial data with provincial trends of child mortality rates. To this end, the percentage growth of neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates were computed for each province during the period. This strategy allows us to represent the overall trends on child mortality indicators at the provincial level in Zimbabwe in three different maps (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4). Negative growth accounts for a percentage decrease on child mortality rates between 1994 and 2015, while positive growth represents an increase in child mortality rates.

In addition, an institutional analysis of child health policies was developed in order to assess if different policies have been implemented in different regions, and if the different results achieved by each province may be understood by the policy strategy implementation during the period.

Three provinces, namely Masvingo, Mashonaland Central and Matabeleland South experienced negative growth in neonatal mortality rates between 1994 and 2015 (Figure 2). All other provinces revealed an increase trend of neonatal mortality rates during the same period.

Similarly, infant mortality rates increased in Harare, Bulawayo, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland Central, Manicaland, Midlands and Matabeleland North between 1994 and 2015, while in Mashonaland West, Masvingo, and Matabeleland South there was a decline in infant mortality rates (Figure 3).

Regarding under-five mortality rates, results show that in Midlands, Matabeleland North, Mashonaland West, Harare, Matabeleland South and Masvingo there was a negative growth pointing to a decrease in under-five mortality rate while in Manicaland, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland Central and Bulawayo there was an increase in under-five mortality rate between 1994 and 2015 (Figure 4). Overall, despite concerted efforts aimed at improving childhood survival, the under-five mortality rate remained relatively high particularly in predominantly rural provinces.

Figure 2. Growth (%) of Neonatal Mortality Rate in Zimbabwe from 1994 to 2015. Source: Developed by the authors with data from the WHO Global Health Observatory data repository. Using: Quantum GIS. Version 3.6.3.

Figure 3. Growth (%) of Infant Mortality Rate in Zimbabwe from 1994 to 2015. Source: Developed by the authors with data from the WHO Global Health Observatory data repository. Using: Quantum GIS. Version 3.6.3.

Figure 4. Growth (%) of Under-five Mortality Rate in Zimbabwe from 1994 to 2015. Source: Developed by the authors with data from the WHO Global Health Observatory data repository. Using: Quantum GIS. Version 3.6.3.

A potential caveat in the national child and maternal health initiatives in Zimbabwe is related to the fact that a uniform policy was designed and implemented for different regions with potentially significant distinct needs, as the heterogeneous evidence on the outcomes of child mortality rates across the country demonstrates. The factors that inhibited equity in maternal care in Zimbabwe are many and they vary from province to province. According to the Demographic and Health Survey conducted in Zimbabwe in 1994, educated mothers have greater knowledge of nutrition, hygiene and other practices relating to childcare and are more likely to utilise health facilities at their disposal. The survey also established that under-five mortality rate was higher in rural areas than in urban areas. However, in cases where there was a decline in mortality rates, the decline was not significant enough to meet the MDG4 target. Our results provide updated evidence supporting this association.

Zimbabwe’s health policy soon after independence revolved around access to health services regardless of geographical location. The central concern of government was extending health facilities and services to every province. Some district hospitals were selected for both expansion and upgrading purposes. The strategy was aimed at alleviating pressure on central hospitals and make modern health facilities accessible to more people, particularly in rural provinces. Central hospitals became referral hospitals to which more complex and uncommon cases would be referred to by the district hospitals (Sanders, 1992). Training of health personnel was invigorated to meet the expansion of the health sector. The government also introduced the village health workers (VHW) program which entailed training of a suitable local community member on health issues (Sanders, 1992). The VHWs would serve the local community there by improving accessibility to health care.

Similarly, the government introduced combined programmes to address the challenges of malnutrition, family planning, and immunization, with the aim of both improving children nutrition standards and fighting the spread of infectious diseases. Trained personnel from the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare would visit schools and vaccinate school children, while Child Supplementary Feeding Programmes were implemented as early as 1992-93 (Munro, 2002). Such strategies adopted in post-colonial Zimbabwe were meant to prevent neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and under-five mortality rates through antenatal and perinatal care, family planning knowledge and HIV/AIDS awareness. According to Sanders (1992), as a result of these nutritional and vaccination strategies, the rural-urban differential in antenatal care was significantly lowered, given that high quality prenatal care enhances the survival prospects of infants.

However, when assessing the impact of the country’s public health policy and strategies for inclusive primary health care, it is importance to also look at the historical context. The worsening economic conditions resulted in frequent shortages of drugs and medical supplies. The declining economic activities particularly among rural communities somehow altered household decisions on the use of health services and facilities. Survival rates became much higher in urban than in rural communities. It has been noted that through resignations, health personnel eventually became overloaded and demotivated. Thus, institutional deficiencies and the critical shortage of skilled personnel also contributed to the provincial variations in childhood mortality rates.

Geographical location of households is also suggested to play an important role in explaining the changes and differences in percentages of the infant mortality, neonatal mortality, and under-five mortality rates in Zimbabwe. Women in urban provinces such as Harare and Bulawayo are more likely to have received antenatal care from medical doctors while women from predominantly rural provinces relied mostly on nurses. According to the Demographic and health Survey (1994), the primary difference in the provision of antenatal care in rural and urban areas lies in the use of physicians. Lack of transport from district hospitals to referral hospitals could be another challenge experienced by rural communities (Karra et al. 2017).

Furthermore, cultural and religious beliefs can be a source of the variance in child mortality rates in Zimbabwe. According to Chitura and Manyanhaire (2013), some women continue to deliver birth at home or delay seeking maternal health care due to religious and cultural factors. However, although underreporting of early childhood mortality is a risk as some traditional communities are not willing to use health facilities on religious grounds, the lack of equipment, inadequate staffing and poor communication remain the main obstacles to the provision of high-quality maternal care in Zimbabwe (Chitura and Manyanhaire, 2013).

Based on current evidence, we can conclude that most of the factors that account for child mortality in Zimbabwe are within the government’s reach, and can therefore be improved by public health programs. The lessons learned with data from the MDG period could be used to reassess the policy planning for the Zimbabwean Sustainable Development Goals agenda regarding child health. Knowledge about the trends and varying mortality rates in Zimbabwe’s provinces is essential for public health policy making, planning purposes, and measuring strides made towards the realization of the country’s human development.

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

Aiken, C. G. A. (1992) “The causes of perinatal mortality in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe”. The Central African Journal of Medicine, Vol. 28, No. 7, 263-81.

Boschi-Pinto, C., Velebit, L., Shibuya, K. (2008) “Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86:710–717.

Central Statistical Office [Zimbabwe] and Macro International Inc. (1995) Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 1994. Calverton. Maryland: Central statistical Office and Macro International Inc.

Chitura, M. and Manyanhaire, I.O. (2013) “Exploring the Determinants of Maternal Dynamics in Zimbabwe”. International Open Learning & Distance Learning Journal, 1(1): 11-18.

Emmanuel, T., Notion, G., Gerald, S., Addmore, C., Mufuta, T., Simukai, Z. (2011) “Determinants of perinatal mortality in Marondera district, Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe, 2009: a case control study”. Pan African Medical Journal, 8:7.

Grépin, K. A., Bharadwaj, P. (2015) “Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe”. Journal of Health Economics, 44, 97-117.

Kambarami, R., Chirenje, M., Rusakaniko, S., Anabwani, G. (1997) “Perinatal mortality rates and associated socio-demographic factors in two rural districts in Zimbabwe”. The Central African Journal of Medicine, 43(6): 158-62.

Karra, M., Fink, G., Canning, D. (2017) “Facility distance and child mortality: a multi-country study of health facility access, service utilization, and child health outcomes.”. The Central African Journal of Medicine, 43(6): 158-62.

Kembo, J., Ginneken, J. K. (2009) “Determinants of infant and child mortality in Zimbabwe: Results of multivariate hazard analysis”. Demographic Research, Vol. 21, 13, 367-84.

Koyanagi, A., Humphrey, J. H., Moulton, L. H., Ntozini, R., Mutasa, K., Iliff, P., Black, R. E., Zvitambo. (2009) “Effect of early exclusive breastfeeding on morbidity among infants born to HIV-negative mothers in Zimbabwe”. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89:1375-82.

Madzingira, N. (1995) “Malnutrition in Children Under Five in Zimbabwe: Effect of Socioeconomic Factors and Disease”. Biodemography and Social Biology, 42:3-4. 239-46.

Munro, L. (2002) “Zimbabwe’s Child Supplementary Feeding Programme: a re-assessment using household survey data”. Disasters, 26(3):242-61.

Nathoo, K. J., Pazvakavamba, I., Chidede, O. S., Chirisa, C. (1991) “Neonatal meningitis in Harare, Zimbabwe: a 2-year review”. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, 11, 11-15.

Root, G. (1997) “Population Density and Spatial Differentials in Child Mortality in Zimbabwe”. Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 413-21.

Rutstein, S. O. (2000) “Factors associated with trends in infant and child mortality in developing countries during the 1990s”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78: 1256-1270.

Sanders, D. (1992) “Health in Zimbabwe since Independence: the potential & limits of Health Sector”, Critical Health No. 40, pp. 52-62.

Sanders, D., Davies, R. (1988) “The Economy, The Health Sector and Child Health in Zimbabwe since Independence”. Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 27, No. 7, pp. 723-731.

Shapiro, R. L., Lockman, S. (2010) “Mortality among HIV-Exposed Infants: The First and Final Frontier”. Critical Infectious Diseases, 50:445-7.

Wagstaff, A. (2000) “Socioeconomic inequalities in child mortality: comparisons across nine developing countries”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78 (1), pp. 19-29.

World Health Organization Database.

Zupan, J. (2005) “Perinatal Mortality in Developing Countries”. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352; 20, pp. 2047-48.

Dr. Arthur A. Catraio holds a Ph.D. in Government from the Brazilian School of Public and Business Administration (EBAPE-FGV), and is a Visiting Scholar at the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences (SPMA-EMS), University of Pretoria. His research interests are in international political economy, social epidemiology, and sustainable development.

Norman Tafirenyika Nhede, PhD is a senior lecturer in the School of Public Management and Administration, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.