Alejandre J, Algones P, Soluta N, Henry R, Lynch M. Child-centered and nutrition-sensitive green spaces: policy recommendations for childhood obesity prevention in the Philippines’ urban poor communities. HPHR. 2022;63. 10.54111/0001/KKK5

Evidence suggests that green spaces benefit children’s physical activity and healthy eating behaviors. However, inequalities on green space availability and accessibility in deprived urban communities in the Philippines compromise the generation of these health outcomes. Urban planning and development in the country mostly focus on developing roads, buildings, and other ‘gray spaces’ with limited considerations on the value of nature-based public health interventions.

In this policy perspective, we examined existing evidence about the impacts of green spaces on childhood obesity and the determinants that influence green space use among children. We then proposed policy measures that could help in the development of child-centered and nutrition-sensitive green spaces in the country’s urban poor communities.

To optimize the health-promoting benefits of green spaces on children’s health; availability, accessibility, type, safety, and social infrastructures should be considered in developing child-centered and nutrition-sensitive green spaces. We recommend that a green space policy should follow a wider multi-sectoral and systems-based approach by considering social, urban planning, financial, educational, and environmental interventions to holistically prevent childhood obesity in the country’s socioeconomically deprived urban communities.

Childhood obesity is a public health concern aggravated by socioeconomic inequalities.1 Globally, 40.1 million children are overweight.2 In the Philippines, increasing child obesity is compounded by unhealthy eating behaviors and physical inactivity, with children in urban communities getting more overweight.3–5 The development of childhood obesity is associated with dietary behaviors, sedentary lifestyle, socioeconomic deprivation, and urbanization.6–9 In effect, obesity makes children vulnerable to diseases, affecting their health and wellbeing.10–12 At macroeconomic level, obesity is associated with poor economic performance due to health costs and human productivity loss.13,14

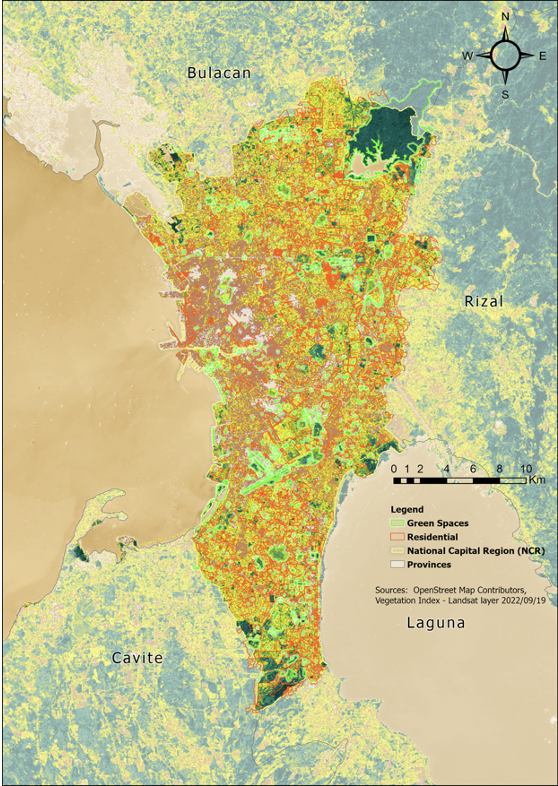

Green space provision is part of a holistic public health approach for developing health-promoting behaviors among children, such as engagement with physical activity and healthy eating.15–18 Studies suggest that neighborhood greenness and exposure to green spaces benefit mental health and behavior of children with special needs.19,20 Moreover, contact with green spaces promote regular physical activity and help improve children’s health-related quality of life. 21–23 Despite the benefits of green spaces on public health, specifically in preventing childhood obesity, many communities do not have accessible green spaces (Figure 1).24,25

Figure 1. Scarcity of green spaces in Metro Manila, Philippines

Dwellers in urban poor communities in the Philippines experience inequitable availability of and accessibility to green spaces.26 Affluent communities have more easily accessible green spaces.27 For this reason, the Philippines’ Department of Health proposed the implementation of a national public open spaces policy to close the gaps on the availability and accessibility of outdoor spaces (e.g., green spaces).28 To help inform the development of this policy, we draw and synthesized existing evidence on the determinants that influence green space use among children. We used this knowledge to propose multi-sectoral policy measures for the co-creation of child-centered and nutrition-sensitive green spaces in the Philippines’ urban context.

We synthesized six determinants that influence green space use among children. These are age, sex, location, availability, accessibility, and social activities present in green spaces.

Younger children have more frequent physical activity in green spaces while school-aged children have longer duration. Moreover, younger children are more active when green spaces have play activities.29 Girls, on the other hand, have low frequency and duration of physical activity in green spaces, especially those from affluent neighborhoods who have better access to motorized transport.29–31

Commonly used green spaces of children are located in schools and residential settings.33–36 Residential green spaces have benefits on children’s physical activity engagement, intensity, and duration.34,37–39 Specifically, children exposed to residential green spaces (i.e., parks, sports fields, nature reserves) spend more time in moderate to vigorous physical activity. Additionally, school-based green spaces (i.e., fields, playgrounds, gardens) could help promote physical activity and vegetable consumption.40–42

The abundance of green spaces is associated with children’s improved nutritional status and increased physical activity.41,43,45 Children in communities without green spaces are likely to become obese due to lack of environmental opportunities to engage with physical activities.41 Moreover, children living closer to green spaces are likely to access these spaces, resulting to increase in physical activity and decrease in screen time.43

Increasing mobility through play provisions, infrastructures, and active transport in green spaces are associated with children’s physical activity.29,44,45 Examples of effective play activities are scavenger-hunting, gardening, playground sports, and nature-orienteering.38,39,41 These could help sustain children’s use and engagement with green spaces for longer duration.29–31,37,38,44–46 Parent’s presence could also impact children’s play activities, while their participation could facilitate green space use.29,39,41,45,46

Green spaces are fundamental to active, healthy, and livable communities.16 Children’s exposure to green spaces has benefits to their physical, mental, and social health.19-21,47–49 Hence, providing accessible green spaces which are adapted to children’s health and nutrition needs is an imperative public health intervention. The plan to implement a national public open spaces policy spearheaded by the Philippine health department is an essential step for the increased appreciation of nature-based public health interventions in the country. To make this policy more inclusive to children’s needs, context- and evidence-based recommendations for child-friendly green spaces, focusing on areas where the health value of green spaces is often overlooked (e.g., social, urban planning, transportation, financing, education, and environment) is crucial. Hence, we provided five policy recommendations to inform the development of child-centered and nutrition-sensitive green spaces for the Philippines’ urban poor communities.

Children in urban poor communities have limited access to green spaces for play and socialization. Considering road congestions, crashes, and lack of child-friendly active transport infrastructures in urban poor communities, pathways to green spaces should have safe and functional pedestrian and cycling facilities.50–52 There is an opportunity to build upon the appreciation for bike lanes and footpaths that proliferated in towns and cities throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.53 Creating an abundance of green spaces through these routes could tackle inequalities in accessibility that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic due to mobility restrictions.54

Dense foliage in green spaces facilitates encouraging environments for children’s play and socialization due to temperature regulation.55 The neighborhood retrofit strategy in Makati City, Philippines could be adapted in high-density urban communities with low green cover.56,57 There is also a culture of fear impacting juveniles’ safety in many cities due to perceived unsafe neighborhoods. Specifically, children perceive their outdoor environments to be impacted by events of child abuse, extrajudicial killings, drug use, and insecurity.58 Children’s living environments should be improved through education, decent housing, rehabilitation, healthcare, employment, and sanitation so they can enjoy livable and sustainable communities where they can optimally thrive.57–59

Children’s clubs provide spaces for health promotion. There is an opportunity to learn and build upon the initiatives of some Filipino youth organizations that provided mini playgrounds, health services for kids, and resources for clean and green projects.58 Another effective example that could be adapted in the Philippine context is the Welsh food club program that helped improve children’s dietary patterns, physical activity, and social skills through free meals, play activities, and nutrition skills training.60

Evidence suggests that nature-based early childhood education is associated with children’s social skills and play engagement.61 For example, Physical Education programs help improve children’s fitness and engagement with physical activities. These could be more effective if delivered in green spaces.62-65 School gardening is also effective in promoting vegetable consumption among children66 and this could be integrated under the Home Economics curriculum as a tool to develop children’s food literacy, with the support from the education and agriculture departments.66,67

Public-private partnership has been widely used to fund the country’s infrastructure programs. For instance, the “Green Green Green” program supporting the development of community-based open spaces could be an opportunity to integrate sustainable green space financing within heavily funded infrastructure programs.68

Green spaces are vital for the prevention of childhood obesity and the promotion of child health and nutrition as these provide opportunities for children to engage in physical activities and healthy eating behaviours.69 However, the inequitable availability of and accessibility to green spaces among Filipino children living in urban poor communities compromise these health outcomes. To co-create child-centered and nutrition-sensitive green spaces in the Philippines’ urban communities, supportive policy and financing facilitated by multi-stakeholder collaboration across health, social service, urban planning, financial, education, and environment sectors at national and local levels are fundamental.

The corresponding author would like to acknowledge Bangor University and the Chevening Scholarship, the UK government’s global scholarship program, funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and partner organizations for the scholarship provided during the conduct of the knowledge synthesis that informed the development of this policy perspective. We would also like to thank Iris Jill Ortiz for creating the Metro Manila green space map for this article.

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Julius is a health promotion specialist with background in health and nutrition policy development and programme planning. He is currently a doctoral researcher and Hydro Nation scholar of the Scottish Government at Glasgow Caledonian University. His areas of work focus on implementation research of nature-based public health interventions, environmentally-informed pharmaceutical prescribing, and sustainable food systems. Julius received his BSc in Nutrition from University of the Philippines Los Baños and MSc in Public Health & Health Promotion from Bangor University in Wales.

Princess is a nutritionist currently working as a consultant for an international NGO. Her areas of work are public health nutrition and data management. She is currently taking her postgraduate degree in public health at University of the Philippines Manila. She received her BSc in Nutrition from University of the Philippines Los Baños.

Nasudi specializes in local nutrition policy and planning and nutrition program management. She is currently on her postgraduate degree in public health (nutrition) at Siliman University. She received her BSc in Nutrition from University of the Philippines Los Baños.

Rachel is a nutritionist with an advisory role for a community-based food project in Scotland. Her areas of work include community-based and public health nutrition initiatives focusing on health inequalities and food insecurity. She received her BSc (Hons) Nutrition from Queen Margaret University and currently taking her postgraduate study in public health at Glasgow Caledonian University.

Dr Mary Lynch is a professor of nursing and healthcare at the School of Health and Life Science of University of West Scotland and a visiting professor at University of South Wales. Her research areas include social return of investment and cost-benefit analysis of public health interventions. She received her PhD in Health Economics at Queen’s University Belfast.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.