Joe J, Cortez J, Lopez J, Villena M, Guinto R. The potential of systems thinking in tackling the wicked problem of childhood obesity in the Philippines. HPHR. 2022;63. 10.54111/0001/KKK2

Obesity among children and adolescents in the Philippines has been on the rise over the last decade, and has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing the ‘wicked problem’ of obesity necessitates an approach that considers the complexity of multiple, interdependent factors at play in the obesogenic system. In current literature, there is a lack of system models that map out obesity systems in the Philippine context. Through a series of workshops involving three middle-income Southeast Asian countries, systems thinking principles and tools were applied to unpack a specific issue related to non-communicable diseases. A cross-sector, multidisciplinary team from the Philippines developed a causal loop diagram to map several contributing factors to childhood obesity in the country, such as individual biological factors, physical inactivity, child’s eating patterns, family lifestyle factors, food retail and advertisement, health literacy, and cultural influences. This exercise aimed to identify potential points of intervention and determine necessary data requirements to run the model. The article notes several limitations as well as recommendations for further improving the obesity system model. Experience from the workshop demonstrates the growing utility of systems thinking to approach complex public health problems and guide policymaking.

Childhood and adolescent obesity rates have increased tenfold globally in the last four decades, from 11 million in 1975 to 124 million in 2016.1,2 While these rates are plateauing in high-income countries, these continue to soar in low- and middle-income countries1, such as the Philippines. In 2019, the Expanded National Nutritional Survey reported a prevalence of overweight at 9.1% and 9.8% among Filipino children (five to 10 years old) and adolescents (11 to 19 years old), respectively.3 The prevalence of overweight among Filipino adolescents has tripled in the last 15 years.4 In general, children and adolescents in the Philippines live in an increasingly obesogenic environment, which fosters sedentary lifestyles and excessive consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and beverages.5 Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these unhealthy eating behaviors and reductions in physical activity by causing disruptions in the everyday routines of children and adolescents6, resulting in the double threat of ‘covibesity’.7,8 Childhood obesity poses a significant public health challenge as it may lead to other associated chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs)9–11, long-term psychological issues9, and direct or indirect future costs in healthcare expenditure and losses in income.5,12–14

There are existing Philippine policies that address nutrition as well as risk factors contributing to obesity, such as the Philippine Plan for Nutrition 2017-2022 and the National Policy on Strengthening the Prevention and Control of Chronic Lifestyle Related Non-communicable Diseases. However, there is no overarching national framework that addresses obesity among children and adolescents.5,15 If no urgent and appropriate action is taken, over 30% of Filipino adolescents are projected to become overweight or obese by 2030.5 The prevention of obesity must start early in the individual’s life course.16 Despite a relatively low prevalence of overweight at 2.9% among Filipino children under 5 years old in 20193, the National Nutrition Council emphasized that preventing obesity needs to start as early as the first 1000 days of life.4 Given the multifaceted nature of the obesogenic environment, the United Nations Children’s Fund’s 2021 landscape analysis highlighted the need for a multi-systems approach to childhood obesity in the Philippines.5

Systems science encompasses a wide-ranging class of analytical approaches that attempt to understand the behavior of complex systems.17 Systems thinking is increasingly being applied to approach ‘wicked problems’, which are ‘resistant, complex, and recurring issues’ with neither definitive formulations nor an optimal set of potential solutions.18,19 Obesity has been labeled as a ‘wicked problem’ since it persists as a result of the complex and dynamic interplay between biological, social, cultural, and built environmental factors.20,21 Some system characteristics that contribute to the complexity of obesity include the heterogeneity of genetic factors and environments such as foodscapes and urban design, the nonlinearity of processes across the life course (e.g. periods of weight loss and gain), and the multiplicity of reinforcing feedback loops that sustain unhealthy behaviors.20

Taking a systems approach to prevent and manage obesity entails multidisciplinary collaboration, particularly between obesity experts and other specialists from disciplines that do not traditionally work on obesity but may potentially contribute to mapping obesogenic systems.21 For instance, urban planners and economists can provide valuable insights on food access as well as pricing and demand, respectively. Additionally, it also involves utilizing innovative systems tools, such as stock and flows diagrams, process mapping, and causal loop diagrams (CLDs).22 As a system dynamics tool, CLDs present qualitative illustrations of mental models that highlight causal relationships, especially feedback loops, among various types of variables in a given system.23 CLDs have been used to model the complex systemic structure of obesity in distinct socio-geographical parameters as broad as the United Kingdom24 and as specific as a Chinese-American community in Manhattan25 to inform evidence-based policy design. A quick search of extant literature revealed the lack of CLD models that map out obesity systems in the Philippine context.

The utility of systems thinking in addressing NCDs, specifically obesity, was demonstrated in the Systems Thinking and Real World Evidence Workshop series held from March 18 to May 13, 2022. This workshop series was led by the SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute (SDGHI) in collaboration with the Planetary and Global Health Program (PGHP) at the St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine (SLMCCM) in the Philippines; Sunway Centre for Planetary Health at Sunway University in Malaysia; and ASEAN Institute for Health Development at Mahidol University in Thailand. This multidisciplinary, cross-sector, and participatory activity involved delegates from three middle-income Southeast Asian countries: Philippines, Malaysia, and Thailand.

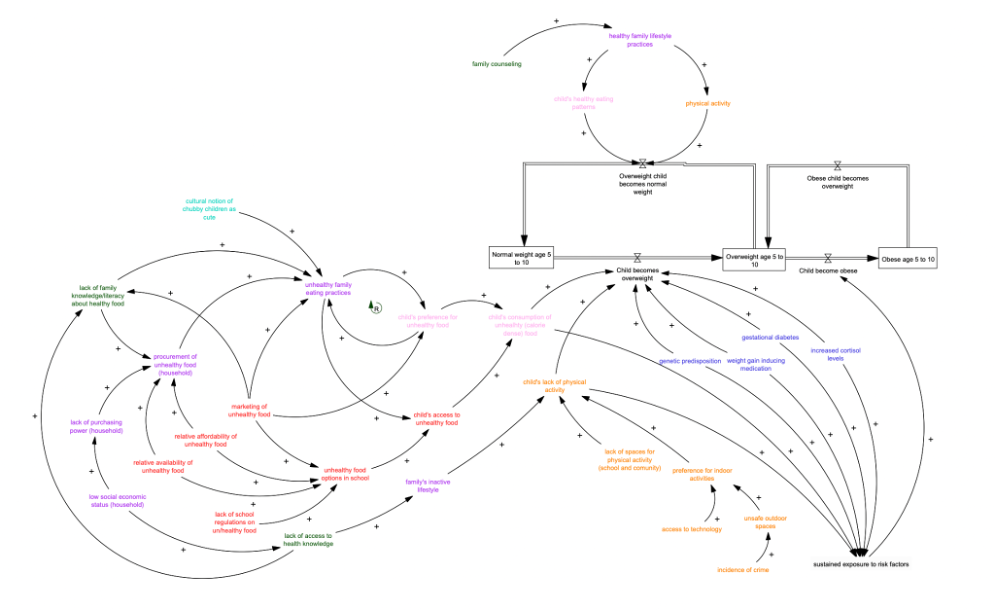

The Philippine delegation is composed of 17 representatives from the government, academia, and civil society, including the authors of this article. Using the Vensim Personal Learning Edition software, this working group developed a CLD model (Figure 1) to broadly map the factors that contribute to the process of becoming overweight among Filipino children ages 5 to 10. As the CLD is being co-developed, seven major clusters of variables were identified: individual biological factors, physical inactivity, child’s eating patterns, family lifestyle factors, food retail and advertisement, health literacy, and cultural influences. Sustained exposure to primary risk factors across these clusters were determined to lead to children from being overweight to becoming obese, reflecting the ‘wicked’ nature of this multifactorial problem.

Figure 1. A causal loop diagram of childhood obesity in the Philippines.

The seven major clusters are color-coded in the diagram: individual biological factors (blue), physical inactivity (orange), child’s eating patterns (pink), family lifestyle factors (purple), food retail & advertisement (red), health literacy (green), and cultural influence (cyan).

Examining the causal and interdependent relationships across the identified variables helped locate possible entry points for policy intervention. Based on the model, several factors that influence children’s access to and preference for unhealthy foods may potentially be addressed by regulating the school’s food environment, particularly by providing healthy menus, supported by nutrition orientations with parents and their children. By setting food standards for canteens, schools can regulate the availability, frequency, and portioning of food products accessible to enrolled children. This can be reinforced through engaging parents and students in nutrition literacy programs to foster healthy family eating habits and positively influence children’s preference towards healthy food.

The Philippine delegation then used the CLD model to reflect on an existing national school-based policy intervention, and necessary data requirements for evaluating the effectiveness of the policy were identified. Some of these needed data include sales records as well as food preference and nutrition literacy surveys among parents and children. Overall, this exercise exemplifies two important applications of systems thinking in analyzing ‘wicked problems’ in public health: to identify critical points for intervention and change17 and determine data requirements for testing and calibrating conceptual models against real-world evidence.22

The Philippine experience from the systems thinking workshop contributes to the growing evidence that systems science provides useful, innovative methods to examine ‘wicked problems’ in public health, such as childhood obesity, to inform decision- and policy-making.

As with any system model, the CLD developed during the workshop is neither perfect nor exhaustive. We note several limitations of the model and its development process, and offer recommendations to address these in future efforts to map obesity systems in the country. Members of the Philippine delegation acknowledge that pathways tracing other upstream drivers of obesity may have been missed in the current model. These include interconnected global food systems26, policies on agricultural development and infrastructure27 as well as social vulnerabilities related to gender inequalities and minority group membership.28

Moreover, the CLD model’s application to a school-based intervention may have led to missing out on specific issues affecting unenrolled school-age children, such as eating habits in foodscapes of informal learning environments29 and outside the school in general. We can also learn from existing CLD models of obesity systems which take into account individual and social psychological factors, such as self-esteem, stress related to ideal body image, and the conceptualization of obesity as a disease.24

In mapping complex obesity systems, we recommend the inclusion of perspectives and experiences of stakeholders from disciplines that were not represented in the delegation, such as economics or agriculture, as well as from school teachers, parents, and children themselves. Shaping the future of policy planning and action for childhood obesity not only entails bridging experts across multiple disciplines but also engaging perspectives from sectors on the ground, moving towards transdisciplinarity.30 For instance, when it comes to managing obesity in adolescents through a primary health care approach, a forthcoming World Health Organization guideline emphasizes that families and communities must be empowered to “take charge of their own health.”31 This may come in the form of long-term community-based interventions that take on a local ‘whole system’ approach, as in London’s Go-Golborne program32, or that target low socioeconomic status and multi-ethnic districts, such as the Dutch Gezond Onderweg! (GO!) program.33 In order to build high-quality primary health care, especially one that is responsive to the obesity epidemic, a systems perspective is paramount.34

While the COVID-19 pandemic has led to societal disruptions that exacerbate obesity in children, it also provides a window of opportunity to rethink and restructure the multiple systems that produce obesity in the Philippines. With schools and other public spaces for children beginning to reopen in the country, it is high time to adopt a multisectoral and transdisciplinary approach informed by systems thinking to address the ‘wicked problem’ of childhood obesity in the coming years.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge all members of the Philippine delegation (see full list below) who have participated in the systems thinking workshop as well as the organizers from the SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute (David Bruce Matchar, MD; John Pastor Ansah, PhD; Amina Mahmood Islam; Tan Teng Sheng Thomas) who have made the activity series possible.

Other members of the Philippine delegation: Armund Arguelles; Christian Joseph Baluyot, RND; Katrina Ceballos, MD, MBA; Ralph Emerson Degollacion; Catherine Duque-Lee MD; Alyzza Vienn Eclavea; Benjhoe Empedrado, MD; Bret Gutierrez, MPH; Miguel Angelo Mantaring, MD; Ildebrando Rodel Ruaya Jr, MHSS, RN, FISQua; Boss Sobremesana, MD; Dasha Marice Uy

Joseph Aaron S. Joe is a Research Associate at the Planetary and Global Health Program of the St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine-William H. Quasha Memorial. He is also affiliated with the Alliance for Improving Health Outcomes, Inc., and was previously engaged as a Research Assistant at the University of the Philippines Manila-Neglected Tropical Diseases Study Group. His work involves qualitative research in health, focusing on health systems and the sociocultural dimensions of health. He earned his bachelor’s degree in Psychology from the Ateneo de Manila University, and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Anthropology at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Jake Bryan S. Cortez, MD is a family and community medicine physician who is currently engaged in projects related to primary health care, quality improvement and patient safety, health professions education, healthcare management, and digital health. He is a Research Fellow at the Planetary and Global Health Program of the St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine-William H. Quasha Memorial, focusing on health systems strengthening. Additionally, he is also a Curriculum Innovations Consultant at the Medical Education Unit and Assistant Professor at the Department of Preventive and Community Medicine of the same institution.

Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, MD, MPM is a physician by profession, specializing in health policy and systems research as a senior lecturer at the College of Public Health, University of the Philippines Manila. He is concurrently vice-president and founding board member of the Philippine Society of Public Health Physicians. His current focus areas are the health workforce, pandemic preparedness, cost-effectiveness of COVID-19 interventions, and public health nutrition. He earned his bachelor’s and medical degrees from the University of the Philippines Manila, and a master’s degree in public management (major in health systems and development) from the Development Academy of the Philippines. He is expected to start a PhD in population health sciences in August 2022 at Duke University as a Biosciences Collaborative for Research Engagement scholar.

Maria Fatima A. Villena is a person living with NCDs and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Center for Policy Studies and Advocacy on Sustainable Development, Inc. (The Policy Center). She is a health activist and has been engaged in development work for over twenty years. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Health Policy Studies (Health Science Track) at the University of the Philippines Manila.

Renzo R. Guinto, MD, DrPH is the Associate Professor of the Practice of Global Public Health and Inaugural Director of the Planetary and Global Health Program of the St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine in the Philippines. Concurrently, he is Chief Planetary Health Scientist and Co-Founder of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. An Obama Foundation Asia-Pacific Leader and Aspen Institute New Voices Fellow, he is a member of several international groups including: Lancet–Chatham House Commission on Improving Population Health post COVID-19 (University of Cambridge); Lancet One Health Commission (University of Oslo); Advisory Board of Climate Cares (Imperial College London); Global Advisory Council of Primary Care International; and Board of Trustees of the Philippine Society of Public Health Physicians. He has served as consultant for various organizations including: WHO; WHO Foundation; World Bank; USAID; and Philippine Department of Health. He obtained his Doctor of Public Health from Harvard University and Doctor of Medicine from the University of the Philippines Manila, and received further training from Oxford, Copenhagen, Western Cape, and East-West Center (Hawaii). He is a former Associate Editor of the Harvard Public Health Review and member of the Boston Congress of Public Health.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.