Vu L. Tackiling COVID-19 in resource-constrained settings:experiences from India and Vietnam. HPHR. 2021;48. 10.54111/0001/VV12

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel strain of the large family of respiratory coronaviruses. It gives rise to a highly contagious disease (COVID-19) transmitted via droplets and close contact. First discovered in Wuhan, China, it rapidly spread across continents and was soon declared a global pandemic. Though majority of people do not develop critical symptoms, many have experienced severe diseases that resulted in hospitalization and death. The millions of COVID-19 cases worldwide means that even a small percentage of critical patients still makes for a large number, potentially placing healthcare systems on the brink of collapse. Consequently, countries began implementing various preventive strategies, prior to the availability of vaccines, to reduce transmission rates. These are categorized into three stages: testing, containment, and mitigation. Testing allows for identification of infections, containment aims to effectively trace and isolate those infected, and mitigation is to slow wider spread of the virus. This paper will discuss the initial COVID-19 responses of India and Vietnam based on these stages as well as how their domestic contexts may have influenced their outcomes. Both are low-resource Asian countries predicted to be amongst the hardest-hit. Nonetheless, despite having similar interventions, while Vietnam became one of the most successful at controlling the pandemic, India’s efforts fell short, resulting in substantial shortages and massive human tragedies. This highlights how pandemic response is a multi-faceted and context-specific process. Hence, examining public health responses in the context of India and Vietnam will contribute to and improve global knowledge of infection control in diverse settings.

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2, has prompted devastating social and economic disruptions across the world. Its rapid progression, being a highly contagious respiratory disease, called for immediate infection control actions.

India and Vietnam are populous countries bordering China, the original epicenter of COVID-19. This puts them at greater risk for large-scale community transmission that would likely overwhelm their limited financial and health resources. Recognising their vulnerability, both countries swiftly took preventive actions to curtail wider spread of the virus. India’s efforts, however, were hampered by challenges unique to its domestic context, resulting in vastly different outcomes. While Vietnam was commended for having one of the best responses to COVID-19, India became the world’s second most-affected country (Nguyen Thi Yen et al, 2021; Choudhury, 2021).

This paper will examine the two countries’ initial responses based on three stages: testing, containment, and mitigation, as well as how their existing public health systems and unique social, behavioral, and contextual aspects could lead to varying degrees of efficacy.

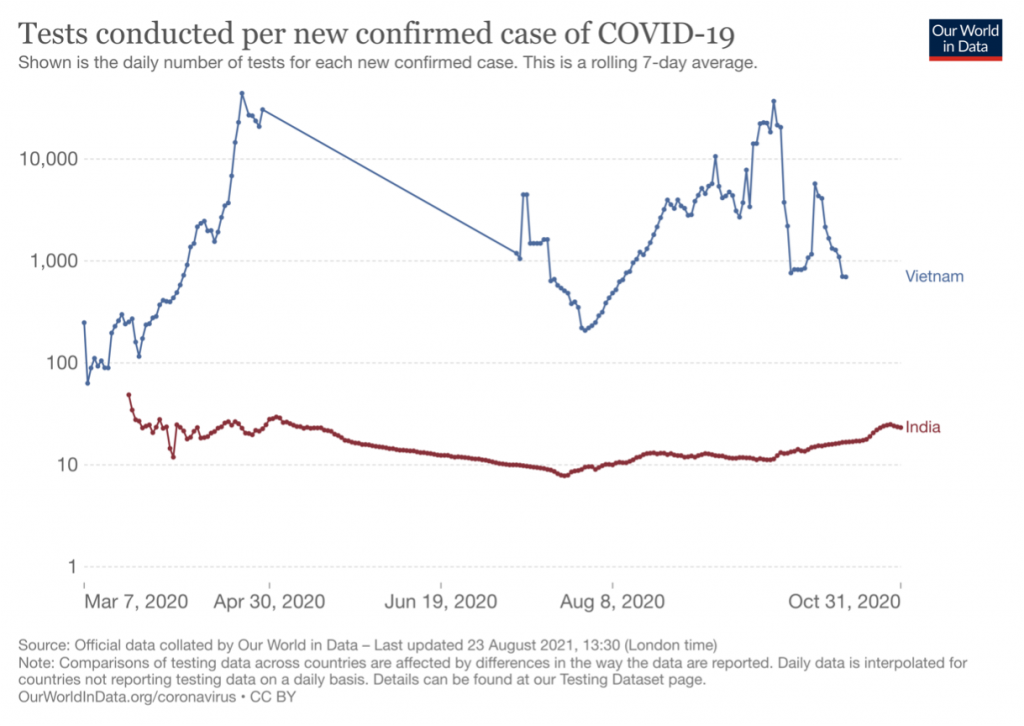

Testing is an important tool for a country to understand the extent of infection and hence adjust control strategies accordingly. It is also critical to reducing transmission rates as most COVID-19 patients are asymptomatic, meaning many cases could go undetected and cause wider spread (Van et al, 2021). Unlike developed countries, India and Vietnam initially lacked the resources for mass testing and hence opted for the low-cost model of selective testing (Reed, 2020). This means focusing on at-risk people, such as those arriving from overseas, residing in outbreak areas, or were exposed to confirmed cases, identified by various surveillance systems (Ibrahim, 2020). Such targeted approach may achieve similar goals as mass testing while being more cost-effective for low- and middle-income countries (Vaidyanathan, 2020).

Since February 2020, Vietnam took aggressive actions in developing locally produced test kits with rapid turnaround time (La et al, 2020). With limited cases at the time, the country made testing its pre-emptive strategy: identify clusters to prevent wider transmission (Pollack et al, 2021). Such proactiveness proved highly effective given the urgent and unpredictable nature of COVID-19. Though India had also made efforts to scale up its testing capacity starting March 2020, it was gravely insufficient for a population of 1.3 billion (Venkata-Subramani & Roman, 2020) (Figure 1). Furthermore, while Vietnam’s testing policy was based on people’s epidemiological status, meaning if they may have been exposed to the virus, India’s strategy relied heavily on people showing symptoms, resulting in silent spread and vastly under counted data (Mukherjee, 2020).

Figure 1: The extent of testing relative to the scale of outbreak in India vs Vietnam

From Our World in Data, by Ritchie et al, 2020. Creative Commons license.

The first COVID-19 cases in India and Vietnam were people arriving from overseas, raising enormous concerns over infection risks from inbound travelers. Both countries promptly instituted travel restrictions and screening at all entry points, followed with mandatory 14-day isolation and daily self-reported health declaration (Gopichandran & Subramaniam, 2020; Bui et al 2020). They were amongst the first countries in the world to close borders, substantially reducing importation of cases.

Once cases were confirmed, India and Vietnam conducted intensive tracing and monitoring of close contacts. Vietnam even went so far as enforcing commune-level lockdowns of areas involving these cases, which likely contributed to their success in sealing off onward transmission without needing a huge amount of testing. Cautious of the high infectivity potential of COVID-19, both countries also quickly issued instructions to quarantine facilities and hospitals on screening, admission, and isolation of patients as well as protocols on proper disinfection. This was important in minimizing nosocomial infection.

Implementing containment strategies, however, posed a major challenge for India as nearly 70 percent of its population reside in rural areas where medical infrastructures are severely ill-equipped (Kumar et al, 2020). Teams of community health activists, such as ASHA, were at the frontlines of India’s effort to address local needs (Peteet et al, 2020). Their hands-on approach, from door-to-door visits, carrying out contact tracing to distributing medicine kits, helped reduce widespread transmissions and provide tailored support to the most vulnerable and marginalized communities (Bajpai & Wadhwa, 2020).

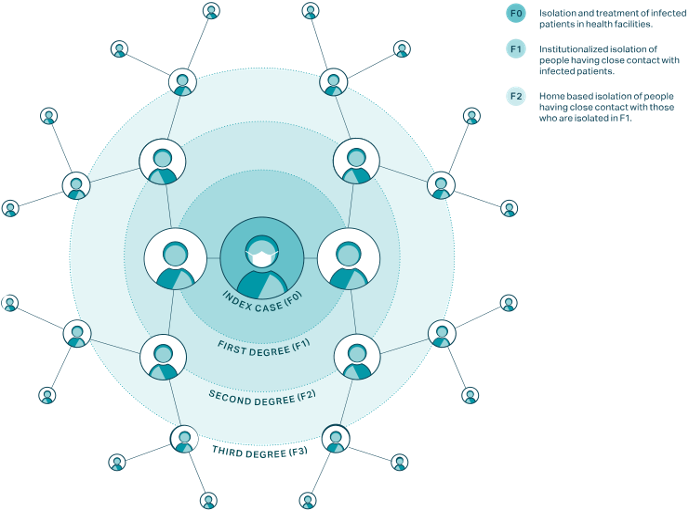

Overall, while their quarantine and travel-related measures were very similar, Vietnam has been praised for its uniquely meticulous contact-tracing effort that India, having a much denser population, was not able to achieve (Nguyen T.A. et al, 2021). Vietnam required every confirmed patient to provide an exhaustive list of people they have met in the last 14 days. These people are then asked to list their own close contacts, allowing tracing all the way to the third contact level (Figure 2). A list of visited locations is also announced to call on people who may have been there at the same time. Irrespective of initial test results, all are to remain in isolation for active monitoring. “That’s one of the unique parts of their response. I don’t think any country has done quarantine to that level”, said Thwaites, an infectious disease expert (Gan, 2020). Such thoroughness allowed the Vietnamese medical system to focus its limited resources on the few critical cases while still managing transmission elsewhere.

Figure 2: Third degree contact tracing in Vietnam

From ‘Emerging COVID-19 success story: Vietnam’s commitment to containment’, by Pollack et al, 2021, Our World in Data. Creative Commons license.

As infection rates outpaced containment strategies, both countries enforced further social distancing measures including closure of schools, non-essential businesses, and banning of sports and entertainment activities to prevent caseloads from overwhelming hospital capacity (Khanna et al, 2020). Ultimately, when Vietnam started seeing a significant number of cases without clear sources, a nation-wide lockdown was instituted. However, mindful of the social impacts of a prolonged full lockdown, after 15 days, Vietnam promptly transitioned back to the targeted approach of mass quarantining only regions deemed “high risk” (Do et al, 2020).

India, on the contrary, implemented its national lockdown very early, when there were relatively low cases localized to specific hotspots, and with only 4 hours notice (Ghosh, 2020). It lasted over 2 months and was considered the most stringent lockdown in the world. As it was hastily prepared, India’s lockdown neglected its most vulnerable populations. Those with chronic conditions were suddenly denied care as health facilities shifted focus to COVID-19 (Hebbar et al, 2020). India’s migrant workers, the majority of its workforce, were deserted without legal or social protection (The Lancet, 2020; Choutagunta et al, 2021). The abrupt lockdown announcement led to mass exodus as panic-stricken workers tried to get home, increasing their chances of exposure and spreading infection at their destinations (Das et al, 2021). Such disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 raise renewed concerns about social disparities, emphasizing the need for a response approach that takes into consideration the housing and working conditions of the most disadvantaged in society.

The purpose of a lockdown is not to eradicate the virus but rather buy time to expand resources and strengthen interventions. Vietnam effectively utilized its lockdown to scale up testing capacity, turn existing infrastructures into designated COVID-19 facilities, and

continue identifying clusters (Van, 2021; Quach & Hoang, 2020). India’s efforts, however, were limited, resulting in new hotspots and a significant spike in cases when lockdown had to be lifted due to economic and social burden, even though it had become more

dangerous (Ghosh, 2020).

Overall, a strict full lockdown did not achieve the same success for a diverse country as India. This highlights the adverse consequences of using the most extreme measure first without careful analysis of socioeconomic context and other strategies in reserve in case wider transmission continues.

India and Vietnam both acknowledged the fundamental role of mass media campaigns in raising awareness and changing people’s transmission-related behaviors. Apart from daily TV broadcasts, regular phone calls and SMS messages reaching rural communities, India developed Aarogya Setu, a similar version of Vietnam’s Bluezone application. These easily accessible phone apps strengthened efforts in contact tracing as well as informing the public of scientific news and preventive policies, such as mask-wearing and physical distancing. It is important in both countries that awareness of these new policies is widespread as they are taken very seriously, with noncompliance subjected to fines (Vaishnav & Vajpai, 2020; Van Nguyen et al, 2021). App-based methods of contact tracing, however, though proved effective for India and Vietnam, is deemed an intrusive approach not applicable for countries with strict regulations on data protection and privacy. Nevertheless, by leveraging the different forms of media, India and Vietnam effectively generated public understanding of the serious threat of COVID-19, debunked misinformation that may hinder control strategies, and conveyed images of government actions to establish trust.

The response of any country to a pandemic is influenced by its existing emergency preparedness. One major reason for the early and rapid actions of both countries is their prior experiences with outbreaks, including SARS (2003), Avian influenza (2004), and Zika (2016) in Vietnam and Nipah virus (2018) in India (Nguyen T.V. et al, 2021; The Lancet, 2020). These experiences contributed to their body of knowledge on health crises, promoting swift and informed decision-making processes and the establishment of crucial public health mechanisms, including emergency operations centre and surveillance system, which they are now able to leverage to tackle COVID-19. India even repurposed drones used in natural disasters to monitor social distancing during lockdown (The Lancet, 2020).

Nonetheless, for an overpopulated country with a high burden of communicable diseases, India’s healthcare system remains too fragmented and under-resourced to cope with a prolonged pandemic. Among developing countries, including Vietnam, India has the lowest spend on healthcare per capita (Kamath, 2017). Limitations in its responses to COVID-19, hence, may be the product of a chronically underfunded public health sector.

On the contrary, through strategic investments in its health system, with public health expenditures per capita increasing consistently every year, Vietnam has built and maintained a system with relatively high surge capacity, expertise, and coordination (Le et al, 2021). Vietnam’s continuing engagement with global health organizations also contributed to their swift development of evidence-based and context-specific prevention and control policies against COVID-19 (Hartley et al, 2021).

The nature and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic calls for sustained and dedicated collaboration between different sectors of society to achieve public health goals.

Vietnam held a pandemic prevention drill, including an army simulation exercise, when only a few cases had been detected (La et al, 2020). This highlights the high level of awareness and proactiveness of the Vietnamese government in responding to health crises. The command-and-control architecture of Vietnam’s governmental system also allowed for synchronized coordination, moving horizontally across the central government and vertically from central to local units. To avoid excessive centralization and for better efficiency, a special task force was established specifically for responding to COVID-19, with the deputy prime minister appointed leader to hold government officials accountable. This group embodies the whole-of-society approach as it comprises many different sectors working together, including 14 ministries, the press, and TV representatives.

Despite also executing through a top-down process, India failed to develop a similarly cooperative relationship between central and state governments. Invoking the Disaster Management Act enabled the central government to impose policies without consulting local states, resulting in one-size-fits-all policies, such as the full lockdown, that neglected differences in incidence rate, resources, and health capacity of different regions (Choutagunta et al, 2021).

While the private sector played a crucial role in Vietnam’s mobilization of resources, there was little involvement from that of India (Gopichandran & Subramaniam, 2020). This is significant as majority of India’s healthcare services have been provided by the private sector, rendering it a key stakeholder (Davalbhakta et al, 2020). Hence, as cases soar, engaging the private sector to share the burden of disease and accelerate responses, including testing capacity, would be imperative to India’s response efforts.

One of the decisive factors in Vietnam’s success was the people’s high adherence to protective guidelines, including mask-wearing and physical distancing (Nguyen N.P.T et al, 2020; Tran et al, 2021). The government’s mobilization of collective effort to “fight against a common enemy” evoked sentiments of nationalism and solidarity, echoing the country’s long war history (Do et al, 2020). This encouraged people to perceive COVID-19 as a serious threat and hence adopt protective behaviors. Surveys suggest Vietnamese people are amongst the most confident in their country’s responses, demonstrated by the outpouring of support and individual donations to the government’s emergency fund throughout the pandemic.

On the other hand, India’s preventive efforts were compromised in part by inconsistent adoption of precautionary measures, most notably the mass gathering events despite surging infections (Puppala et al, 2021; Sahu et al, 2020). India’s distinctive socio-cultural and religious heterogeneity makes it particularly difficult to promote unanimous adherence over a long period of time (Datta et al, 2021; Joshi et al, 2021). This reinforces how cultural and social characteristics of each society can influence the efficacy of specific health policies, leading to differing outcomes even with similar interventions.

Despite high population density and limited resources, both India and Vietnam benefited immensely from taking a preventive approach against COVID-19, including testing, isolation, and movement restriction, to reduce the need for curative measures. Nevertheless, India’s domestic context posed unique challenges that compromised the effectiveness of such approach. This highlights the importance of tailoring public health measures to local contexts. Vietnam’s rigorous but sensible interventions and their unified whole-of-society approach contributed to a strong pandemic preparedness.

Although it is difficult to assess effectiveness for an ongoing and rapidly changing crisis, pandemic responses of India and Vietnam still offer valuable lessons especially for populated and resource-constrained settings.

The author has no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

I wish to express my deepest gratitude and profound thanks to my editors, Bolu Alabi and Binh Vu, for your precious time and constant encouragement throughout this process.

Bajpai, N., & Wadhwa, M. (2020). COVID-19 in Rural India. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8-RJYK-MM69

Bui Thi Thu, H., La, N. Q., Tolib, M., Nguyen Trong, T., Pham Quang, T., & Phung Cong, D. (2020). Combating the COVID-19 epidemic: Experiences from Vietnam. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3125.

Choudhury, S. R. (2021, April 12). India overtakes Brazil to become the second-worst hit country as Covid cases soar. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/12/coronavirus-india-becomes-second-worst-hit-country-as-covid-cases-surge.html

Choutagunta, A., Manish, G. P., & Rajagopalan, S. (2021). Battling COVID-19 with dysfunctional federalism: Lessons from India. Southern Economic Journal, 87(4), 1267–1299.

Das, J., Khan, A. Q., Khwaja, A. I., & Malkani, A. (2021). Preparing for crises: Lessons from covid-19. LSE Public Policy Review, 1(4). https://doi.org/10.31389/lseppr.32

Datta, S., Chakroborty, N. K., Sharda, D., Attri, K., & Choudhury, D. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic in India: Chronological comparison of the regional heterogeneity in the pandemic progression and gaps in mitigation strategies. In Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-666506/v1

Davalbhakta, S., Sharma, S., Gupta, S., Agarwal, V., Pandey, G., Misra, D. P., Naik, B. N., Goel, A., Gupta, L., & Agarwal, V. (2020). Private health sector in India-ready and willing, yet underutilized in the covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 571419.

Đo Tá Khánh, Hansen, A., Hardy, A., Pham Quỳnh Phương, Shum, M., Wertheim-Heck, S. C. O., & Vũ Ngoc Quyên (2020). Vietnam’s COVID-19 strategy: Political mobilisation, targeted containment, social engagement. European Commission.

Gan, N. (2020, May 30). How Vietnam managed to keep its coronavirus death toll at zero. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/29/asia/coronavirus-vietnam-intl-hnk/index.html

Ghosh, J. (2020). A critique of the Indian government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Economia e Politica Industriale, 47(3), 519–530.

Gopichandran, V., & Subramaniam, S. (2020). Response to Covid-19: An ethical imperative to build a resilient health system in India. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, V(2), 1–4.

GRID COVID-19 Study Group. (2020). Combating the COVID-19 pandemic in a resource-constrained setting: insights from initial response in India. BMJ Global Health, 5(11), e003416.

Hartley, K., Bales, S., & Bali, A. S. (2021). COVID-19 response in a unitary state: emerging lessons from Vietnam. Policy Design and Practice, 1–17.

Hebbar, P. B., Sudha, A., Dsouza, V., Chilgod, L., & Amin, A. (2020). Healthcare delivery in India amid the Covid-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 1–4.

Ibrahim, N. K. (2020). Epidemiologic surveillance for controlling Covid-19 pandemic: types, challenges and implications. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13(11), 1630–1638.

Joshi, A., Mewani, A. H., Arora, S., & Grover, A. (2021). India’s COVID-19 burdens, 2020. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 608810.

Kamath, S., & Kamath, R. (2017). Does India really not have enough money to spend on healthcare? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 93(1103), 567–567.

Khanna, R. C., Cicinelli, M. V., Gilbert, S. S., Honavar, S. G., & Murthy, G. S. V. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned and future directions. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 68(5), 703–710.

Kumar, A., Rajasekharan Nayar, K., & Koya, S. F. (2020). COVID-19: Challenges and its consequences for rural health care in India. Public Health in Practice (Oxford, England), 1(100009), 100009.

La, V.-P., Pham, T.-H., Ho, M.-T., Nguyen, M.-H., P. Nguyen, K.-L., Vuong, T.-T., Nguyen, H.-K. T., Tran, T., Khuc, Q., Ho, M.-T., & Vuong, Q.-H. (2020). Policy response, social media and science journalism for the sustainability of the public health system amid the COVID-19 outbreak: The Vietnam lessons. Sustainability, 12(7), 2931.

Le, T.-A. T., Vodden, K., Wu, J., & Atiwesh, G. (2021). Policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 559.

Mukherjee, K. (2020). COVID-19 and lockdown policy: Insights on the Indian situation. https://doi.org/10.33774/coe-2020-l1g3b

Nguyen, N. P. T., Hoang, T. D., Tran, V. T., Vu, C. T., Siewe Fodjo, J. N., Colebunders, R., Dunne, M. P., & Van Vo, T. (2020). Preventive behavior of Vietnamese people in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS One, 15(9), e0238830.

Nguyen, T. A., Nguyen, B. T. C., Duong, D. T., Marks, G. B., & Fox, G. J. (2021). Experience in responding to COVID-19 outbreaks from Vietnam. The Lancet Regional Health. Western Pacific, 7(100077), 100077.

Nguyen, T. V., Tran, Q. D., Phan, L. T., Vu, L. N., Truong, D. T. T., Truong, H. C., Le, T. N., Vien, L. D. K., Nguyen, T. V., Luong, Q. C., & Pham, Q. D. (2021). In the interest of public safety: rapid response to the COVID-19 epidemic in Vietnam. BMJ Global Health, 6(1), e004100.

Nguyen Thi Yen, C., Hermoso, C., Laguilles, E. M., De Castro, L. E., Camposano, S. M., Jalmasco, N., Cua, K. A., Isa, M. A., Akpan, E. F., Ly, T. P., Budhathoki, S. S., Ahmadi, A., & Lucero-Prisno, D. E., 3rd. (2021). Vietnam’s success story against COVID-19. Public Health in Practice (Oxford, England), 2(100132), 100132.

Peteet, J. O., Hempton, L., Peteet, J. R., & Martin, K. (2020). Asha’s response to COVID-19: Providing care to slum communities in India. Christian Journal for Global Health, 7(4), 52–57.

Pollack, T., Thwaites, G., Rabaa, M., Choisy, M., Doorn van R., Le V. T., Duong H. L., Dang Q. T., Tran D. Q., Phung C. D., Ngu D. N., Tran A. T., La N. Q., Nguyen C. K., Dang D. A., Tran N. D., Sang M. L., Thai P. Q., Vu D., and Exemplars in Global Health. (2021, March 5). Emerging COVID-19 success story: Vietnam’s commitment to containment. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-vietnam

Puppala, H., Bheemaraju, A., & Asthana, R. (2021). A GPS data-based index to determine the level of adherence to COVID-19 lockdown policies in India. Journal of Healthcare Informatics Research, 5(2), 1–17.

Quach, H.-L., & Hoang, N.-A. (2020). COVID-19 in Vietnam: A lesson of pre-preparation. Journal of Clinical Virology: The Official Publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology, 127(104379), 104379.

Reed, J. (2020, March 24). Vietnam’s coronavirus offensive wins praise for low-cost model. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/0cc3c956-6cb2-11ea-89df-41bea055720b

Ritchie, H., Mathieu, E., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Giattino, C., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Hasell, J., Macdonald, B., Beltekian, D., & Roser, M. (2020). Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing

Sahu, K. K., Mishra, A. K., Lal, A., & Sahu, S. A. (2020). India fights back: COVID-19 pandemic. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 49(5), 446–448.

The Lancet. (2020). India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet, 395(10233), 1315.

Tran, L. T. T., Manuama, E. O., Vo, D. P., Nguyen, H. V., Cassim, R., Pham, M., & Bui, D. S. (2021). The COVID-19 global pandemic: a review of the Vietnamese Government response. Journal of Global Health Reports. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.21951

Vaidyanathan, G. (2020). People power: How India is attempting to slow the coronavirus. Nature, 580(7804), 442.

Vaishnav, V., & Vajpai, J. (2020). Assessment of impact of relaxation in lockdown and forecast of preparation for combating COVID-19 pandemic in India using Group Method of Data Handling. Chaos, Solitons, and Fractals, 140(110191), 110191.

Van Nguyen, Q., Cao, D. A., & Nghiem, S. H. (2021). Spread of COVID-19 and policy responses in Vietnam: An overview. International Journal of Infectious Diseases: IJID: Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, 103, 157–161.

Van Tan, L. (2021). COVID-19 control in Vietnam. Nature Immunology, 22(3), 261.

Venkata-Subramani, M., & Roman, J. (2020). The Coronavirus response in India – world’s largest lockdown. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 360(6), 742–748.

Linh Vu is a third-year medical student at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. She has keen interests in global public health, specifically the provision of surgical care.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.