Kahane K, Morof J. Child and adolescent mental health access in the U.S.: a multifactorial challenge with dynamic policy. HPHR. 2021;34.

DOI:10.54111/0001/HH9

On March 11, 2021, The American Rescue Plan Act allocated 80 million dollars in grants to increase mental health access for children and adolescents. This provision lent needed attention and validation to the tremendous treatment gaps in child and adolescent mental health care, an issue with high costs to the health system, and short and long-ranging impacts. Most child mental illnesses go untreated and hurdles to access, including social factors and geography, play prominent roles. This paper will give a brief background of the epidemiology of child mental illness in the US and then discuss some of the challenges in mental health access among children and adolescents in the US. Further, proposed and ongoing solutions will be discussed to address the challenge of unequal distribution of care and the sheer lack of capacity. These approaches include expanding the training landscape, using a WHO resource conservation model, tele-mental health, and primary care-specialist partnerships. These approaches lend policymakers and stakeholders a preliminary analysis of how these funds could be allocated and thereby have tremendous importance for the current moment.

In 2019, it was estimated that 22% of children in the United States, or 13 million children, have at least one mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder.2 Despite this, the national prevalence of children with a mental health disorder who did not receive needed treatment or counseling from a mental health professional has been estimated to range between 49.4% and 80%.2,3 Access to pediatric mental health care differs by geography, socioeconomic status, race, and other social factors.4,5,6

It is estimated that 13 million children and adolescents suffer from mental illness in the U.S. The most common diagnoses are behavioral disorders, anxiety, and depression.7 Specifically, among children ages 2 to 17, 9.4% have received an ADHD diagnosis, 7.1% a diagnosis of anxiety, and 3.2% have been diagnosed with depression. Many of these disorders are associated with other comorbidities. For example, it is estimated that 3 in 4 children with depression also suffer from anxiety, and that among children with anxiety, 1 in 3 have behavioral problems as well.8

Children who endure adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including neglect and physical or sexual abuse, are more likely to suffer from a mental or behavioral disorder.9 Socioeconomic status also features prominently; the prevalence of mental health disorders is increased in children living below the federal poverty level.10 From an equity perspective, it is important to note that while the poorest children tend to be most likely to suffer from mental illness, they are also the least likely to have access to adequate care and treatment, as will be discussed further in this paper.11

In the short term, untreated depression can put children at risk for withdrawal, social isolation, or suicide.12 Untreated ADHD can lead to underperformance in school and executive function difficulties in performing tasks. Anxiety has risks for social isolation and difficulty forming relationships, as well as somatic symptoms that can present in medical settings related to sleep, eating, GI function, and headaches.13 Moreover, untreated mental health portends tremendous risks for the future. Childhood psychiatric disorders are linked to negative outcomes like poor social mobility and future unemployment.14

Given the high prevalence of mental health disorders in children and the significant benefit treatment provides across the life span, questions surrounding access to treatment are critical.15 It is therefore troubling that 49% to 80% of children with mental health disorders go without treatment.2,3 For those who do receive care, it is estimated that the delay between symptom onset and first treatment contact is nearly a decade.16 A primary cause of the limited treatment for mental health disorders in children is the dearth of child and adolescent mental health specialists. Over 15 million children and adolescents in the US have at least one mental health disorder, yet there are only 8,300 practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists (CAPs) in the United States.17

The U.S. Bureau of Health Professions projected demand for child and adolescent psychiatry services would double between 1995 and 2020.17 This increased projected demand is multifactorial, likely due to an increase in the population under age 18, improved screening and diagnostic tools for child mental health disorders, greater insurance coverage for children, and an increased prevalence of certain mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and autism spectrum disorder.17,18,19 Given the expected increase in demand for services, it is surprising that the number of CAP residency training programs decreased between 1990 and 2003, as did the number of individuals in CAP residency programs.17 Since 2004, over 20 new CAP training programs have opened and the number of CAP residents has increased from 709 in 2004 to 858 in 2017. This has led to a 26% increase in the number of CAPs, far below the expected number of providers necessary to meet demand.19

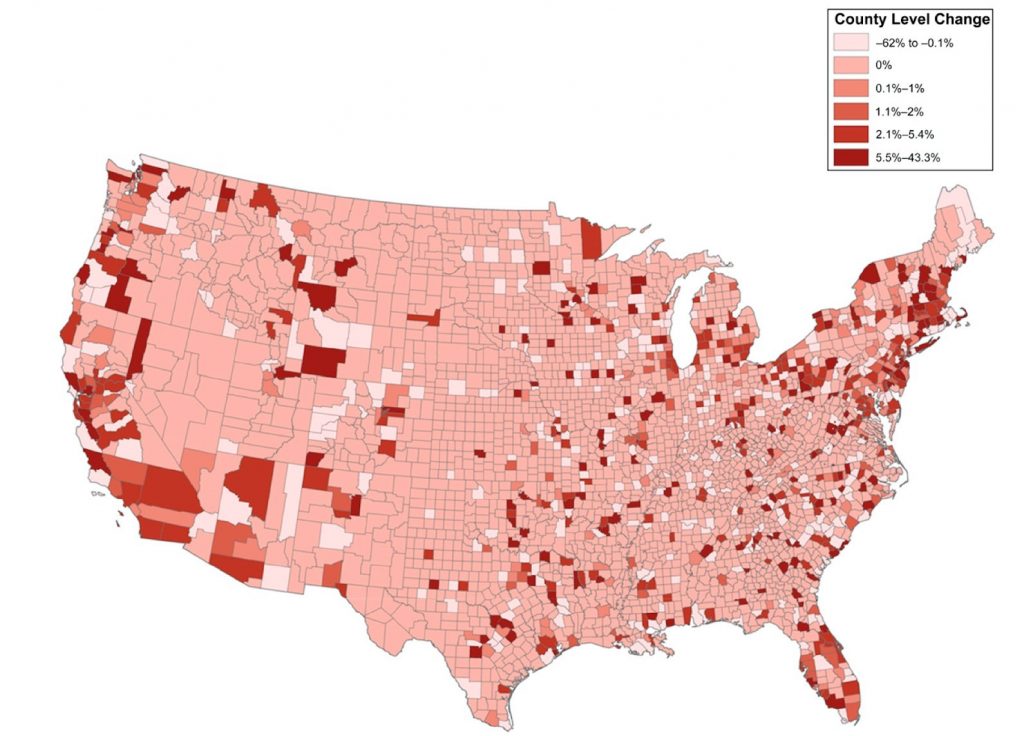

As a result of the limited growth in child mental health practitioners, no state or territory has a sufficient supply of CAPs, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP).20 There is significant variation in access to CAPs across the country. For example, though Oklahoma, Indiana, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee together have five times as many children as Massachusetts, Massachusetts has the same number of child and adolescent psychiatrists as the former states combined.19 41 states and Puerto Rico have a severe shortage of CAPs (defined by AACAP as 1-17 CAPs per 100,000 children), while nine states and the District of Columbia have only a high shortage of CAPs (defined as 18-46 CAPs per 100,000 children). While the ratio of CAPs to children increased by 50% in six states, another six states saw a declining ratio. This trend was seen at a county level as well, where much of the growth in CAPs was observed in coastal counties (See Appendix, Figure 1).19 Further, CAPs are more likely to practice in counties with higher average household incomes, higher levels of postsecondary education, and metropolitan counties. At least 70% of counties in the United States have no CAPs at all.

The disparity in access to treatment for mental health disorders is greater amongst racial and ethnic minority groups, uninsured children, and children living in rural areas. Compared with white children, Black and Latino children receive less mental health treatment, including treatment for substance use disorder.21 In the 1996-1998 National Health Interview Survey, 80% of Black children and 82% of Hispanic children with mental health disorders did not receive treatment, compared with 72% of white children.21 This disparity persists even after accounting for income, health insurance, mental health impairment, and other demographic factors. Moreover, when children from racial minority groups do receive treatment for their mental health disorders, they are more likely to receive care from a primary care provider, rather than a child mental health specialist.21

Poverty is highly correlated with child mental illness and decreased access to care. Areas with decreased access to mental health providers likely have lower reported prevalence due to lack of diagnosis.22 Children in the welfare system also have been shown to have high mental health needs and poor access to mental healthcare.23,24

Uninsured children have decreased access to mental health treatment compared with insured children.21 Only 4 to 5% of uninsured children receive treatment for mental health disorders, compared with 5 to 7% of privately insured children and 9 to 13% of publicly insured children. This suggests that public insurance programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program play an important role in helping children access mental health providers.

For rural children, there is a confluence of factors that makes them more likely to both suffer from a mental illness and have difficulties accessing care compared to their urban counterparts.25,26 This has made access in rural areas the focus of academic, advocacy, and policy interest. Rural areas have been shown to have a decreased density of mental health professionals than urban areas.27 Specifically, in 2018 it was found that 68% of rural counties did not have a single psychiatrist.28

This trend possibly relates to larger trends in health care access. In 2011 it was found that rural children were less likely to have received preventative care and oral health care than their urban counterparts.29 Moreover, rural settings typically offer fewer evidence-based, early-intervention programs than urban settings. Evidence suggests that these early-intervention programs might help prevent or mitigate some cases of mental and behavioral disorders.30 Transportation is also a barrier and has been cited “as one of the major concerns reported by rural residents in discussing limitations to their access to health care.”31 Additionally, 1 in 4 rural children live in poverty (compared to 1 in 5 nationwide).32 Further study is needed to understand the weight of each of these factors which come together to make rural areas such a focus for this problem.

Lack of access to child mental health care has two overarching etiologies: a shortage of mental health providers and inequitable distribution of resources. Addressing the lack of capacity requires training more mental health professionals and reconsidering where, when, and what kinds of professionals are utilized. To address the inequitable distribution of resources, effective approaches bring existing resources from areas of saturation to areas of sparsity. Specialized state programs and telemedicine platforms can assist in the redistribution of child mental health providers.

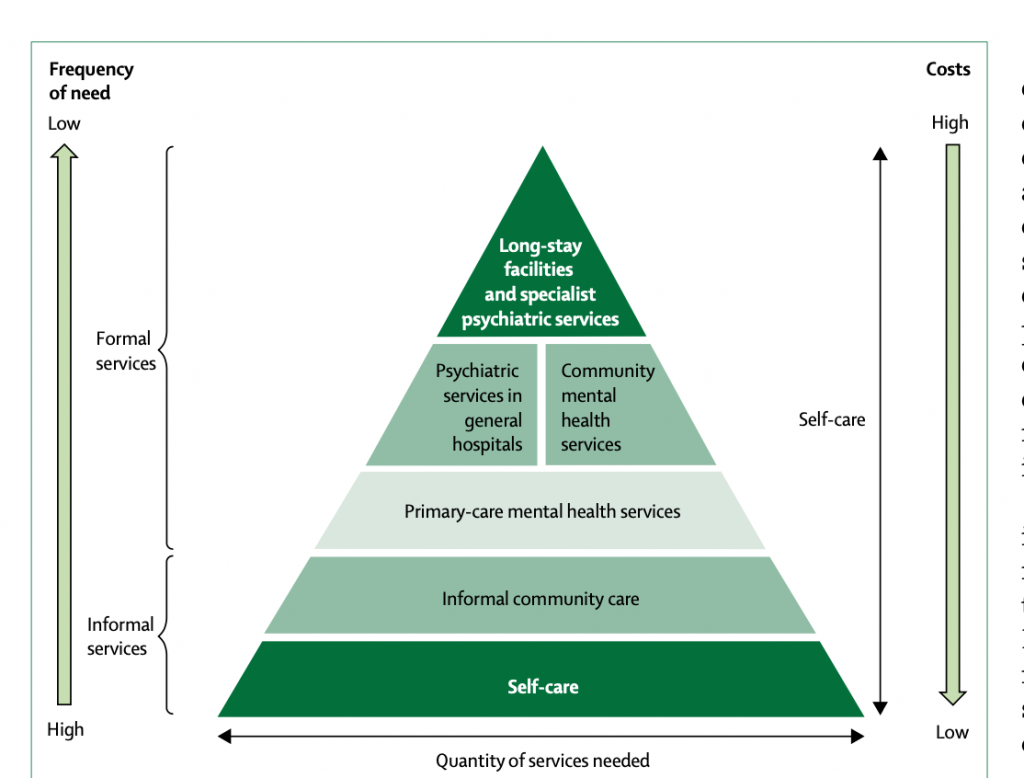

To address the lack of capacity, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests a pyramid service organization model for mental health care that seeks to conserve the most expensive, resource-intensive services and increase capacity for more mild treatment with primary care and self-care (see Appendix A for WHO Mental Health Access Pyramid). The WHO pyramid suggests that mild mental health issues such as very mild anxiety/depressive symptoms can be treated via self-care or informal community care, whereas more moderate depression would be treated by a primary care provider (PCP) and more serious depression in a community clinic, or by a psychiatrist. This approach thinks critically about who is treating what and assumes a sparsity of child psychiatrists along with a more robust group of primary care providers. This WHO pyramid was designed to be applied to both lower and middle-income countries, as well as wealthy countries such as the U.S.33

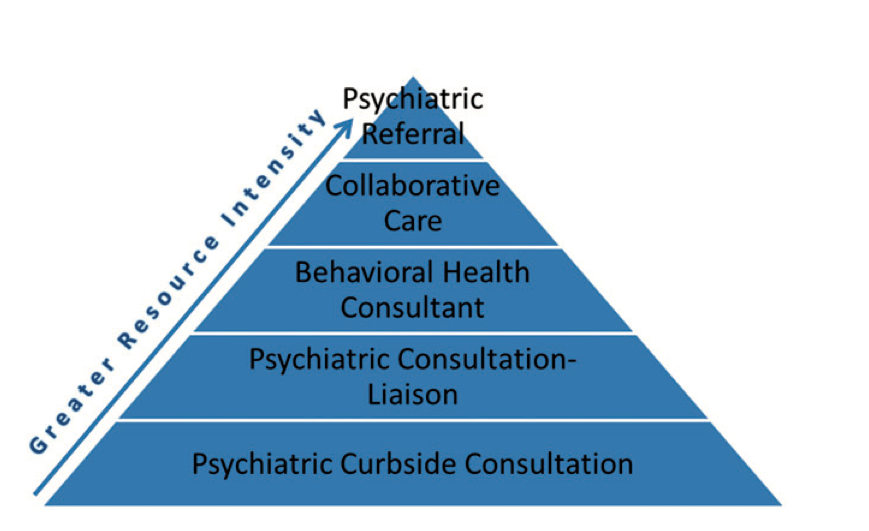

To address the inequitable distribution of resources, telehealth is a powerful tool. Many studies show clear effectiveness and feasibility of telepsychiatry for mental health, and that with a high-quality video and a good internet connection, telehealth is as effective as in-person psychiatric care and therapy.34 Moreover, telepsychiatry is especially powerful in reaching rural Americans with the already existing mental health workforce.35 Telehealth itself can be approached using a pyramid model, similar in concept to the WHO pyramid mode, which expands access even further, by utilizing the least available resources for patients with the most severe mental illness, and calling on primary care as a critical touchpoint in more mild and moderate mental illness (see Appendix B for Telemedicine Pyramid).

Over the course of the pandemic, telemedicine for mental health has become increasingly common.36 Specifically with regards to children, a 2021 Child Mind Institute poll found that seven in ten parents with a child who utilized mental health services in the past 12 months did so via telehealth.37

Many of the barriers to adopting the use of telemedicine for mental health treatment, from acceptability to parity laws, have lessened during the pandemic as telehealth has become the norm. Parity laws refer to the requirement that payers reimburse telehealth at the same rate as in-person care (parity reimbursement) and for insurance to cover telehealth at all (coverage reimbursement).38 These laws were previously a tremendous barrier to telehealth access. Prior to COVID-19, just five states had parity laws in place for telehealth, but recent analyses have shown that an additional 21 states expanded telehealth services through COVID-19 emergency orders, with 13 requiring payers to meet this standard of parity. Most remarkably, 48 states have amended Medicaid policy to expand Medicaid reimbursement of telehealth services.39 Stakeholders have pushed for improving telehealth systems and policies that enable reimbursement and coverage parity to continue past the pandemic.40

Even with these important policy changes, there are several limitations to telehealth, particularly for children. Psychotherapy for young children, especially toddlers and young school-aged kids often relies on play therapy where the provider learns about the child’s affect, behavior, and thought content through organic play. This can be challenging in the telemedicine context since being on camera creates barriers for the child to candidly engage and for the provider to observe and play along.41 Moreover, telehealth relies on families to have a computer, a stable internet connection, and some degree of digital literacy. A 2019 Pew report found that among families with an annual household income below $30,000, 44% do not have home broadband services and 46% lack a traditional computer.42 A study in Health Affairs in 2021 found that telemedicine usage during the COVID-19 pandemic was lower in communities with high rates of poverty.43

Improving access to mental health treatment for youth requires increasing the number of practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists. The 8,300 CAPs currently practicing in the United States is far below the 30,000 projected to be needed by the Council on Graduate Medical Education.17 It is unclear whether expanding residency programs to fill this tremendous 22,000 provider gap will help, as a significant portion of the existing CAP fellowship training positions are not filled. Of the 1,132 fellowship training positions in child and adolescent psychiatry, 249 of the positions, or 22%, went unfilled.44 This suggests the capacity to train CAPs in the United States far outweighs the demand by physicians to enter the field. Thus, solutions are needed to target increased recruitment at the medical student level.

Part of the difficulty attracting physicians to the field is a lack of exposure among medical students to child and adolescent psychiatry. The majority of medical students have no clinical rotations in child and adolescent psychiatry, and 20% of medical schools in the U.S. do not offer elective clerkships in the field.44 Increasing exposure to child and adolescent psychiatry during medical school may help increase interest in the field. As most medical students are required to take a general psychiatry and pediatrics clerkship, a potential solution is to incorporate child and adolescent psychiatry into either of these rotations.

Moreover, psychiatrists receive lower in-network compensation for services compared to other medical specialties, and this certainly contributes to decreased interest in the field. Notably, it also contributes to a growing trend of CAPs not accepting insurance and instead having patients pay for services out of pocket or with out-of-network reimbursement when available. To combat this trend, it is important to consider whether higher in-network reimbursement for child and adolescent psychiatric services would reduce the need for those with insurance to pay out of pocket for treatment.45

It is important to note that part of the shortage in CAPs is offset by primary care providers, including pediatricians. PCPs are spending an increasing portion of visits treating patients with behavioral, emotional, developmental, psychosocial, and educational concerns.3 However, while PCPs today are more frequently tasked with diagnosing and treating psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents, the American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes several barriers to pediatricians being able to deliver mental health care treatment.3 These include “insufficient time, training, knowledge of local resources, and access to specialists.”3

Still, PCPs have an important role to play in the management of mental health disorders in children. Given the shortage of CAPs, programs that can assist pediatricians in diagnosing and treating mental health disorders can help improve access to treatment. One such model designed to support primary care providers, especially pediatricians, in screening, diagnosing, and treating children with mental health disorders is the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project (MCPAP).46

Using a telemedicine model, MCPAP leads several teams throughout Massachusetts consisting of CAPs, licensed therapists, and care coordinators. PCPs can call a child and adolescent psychiatrist at MCPAP to receive assistance with diagnosing or treating a patient with a mental health disorder. Patients with more complex mental health needs can be referred to MCPAP for a face-to-face consultation or for assistance finding a provider in the community. MCPAP is available to all PCPs in the state regardless of a patient’s insurance status. MCPAP partners closely with academic medical centers across the state and is funded through the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. MCPAP is explicitly focused on expanding the field of primary care child psychiatry. By improving the ability of PCPs to prevent and screen children for mental health disorders and by aiding in the treatment of mild to moderately complex mental health disorders in children, MCPAP works to improve access to treatment for children with mental health disorders. The model created by MCPAP is highly efficient and costs only $2.20 per child in Massachusetts to operate, for a total of $3.3 million annually. MCPAP is a cost-effective solution to expanding access to evidence-based treatment for children with mental health disorders and should be considered by other states.

This paper has considered the serious and widespread issue of limited access to treatment for child mental health disorders in the United States, and the multiple factors which contribute to and exacerbate this problem. The burden of child mental health access is significant and cuts along economic, racial, ethnic, and geographic lines. The issue of limited access to treatment of child mental health disorder is rooted in both a shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists and inequitable distribution of resources.

To help with decreased capacity, the WHO’s pyramid approach can help conserve more resource-intensive services for children and adolescents with the most severe mental health disorders. Additional efforts should be made to increase the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists, starting by efforts to bolster interest in the field beginning in medical school. To address the issue of inequitable resource distribution, telemental health can help bring available providers to areas of scarcity. Recent policy changes have made telemental health a more feasible option during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the existing digital divide means that telemental health is an imperfect solution. Ultimately, partnerships between child and adolescent psychiatrists and primary care providers offers the most promise for closing this access gap.

Figure 1. County-level Change in child psychiatrists per 100,000 children (2007-2016)

Reprinted from “Growth and Distribution of Child Psychiatrists in the United States” by AMcBain RK, Kofner A, Stein BD, Cantor JH, Vogt WB, Yu H. Pediatrics. 2007-2016.

Figure 2. WHO Pyramid Model

Reprinted from The WPA-Lancet Psychiatry Commission on the Future of Psychiatry by Bhugra, D., Tasman, A., Pathare, S., Priebe, S., Smith, S., Torous, J., … Ventriglio, A. The Lancet Psychiatry. (2017).

Figure 3. Telepsychiatry Pyramid Model.

Reprinted from Telepsychiatry integration of mental health services into rural primary care settings. By Fortney, J. C., Pyne, J. M., Turner, E. E., Farris, K. M., Normoyle, T. M., Avery, M. D., Hilty, D. M., & Unützer, J. International review of psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 27(6), 525–539. (2015).

Kelila Kahane recently graduated with an MPH from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and is a medical student at SUNY Downstate College of Medicine. Her interests include mental health, health access equity, and digital health. She intends to practice as a child and adolescent psychiatrist.

Joshua Blake Morof, MPH, Joshua Morof recently graduated with a Master of Public Health from the Harvard Chan School of Public Health and is a fourth-year medical student at Wayne State University School of Medicine. He is planning to go into pediatric residency after medical school.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.