Tejan M. Part III: Case study: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Cameron County, Texas. HPHR. 2021; 31.

DOI:10.54111/0001/EE8

As noted in Vaccine Hesitancy, Misinformation, and COVID-19, health misinformation can lead to damaging behaviors in emergency settings such as vaccine hesitancy. One U.S. community, however, appears to be at least marginally protected from the behavior changes associated with health misinformation: Cameron County, Texas. Cameron County has been an epicenter in the U.S. for public health emergencies such as H1N1, Zika virus, and now COVID-19. Despite this, the county continues to be largely responsive to public health interventions and has been minimally impacted by misinformation in public health emergencies. Further research is needed to understand why and how Cameron County has been largely unaffected by health misinformation.

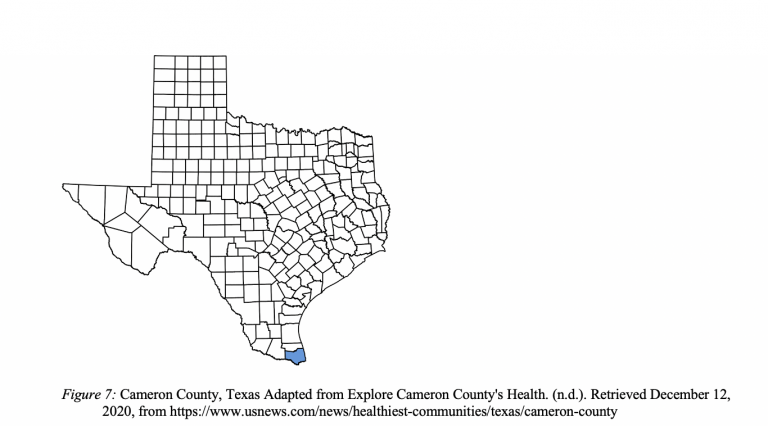

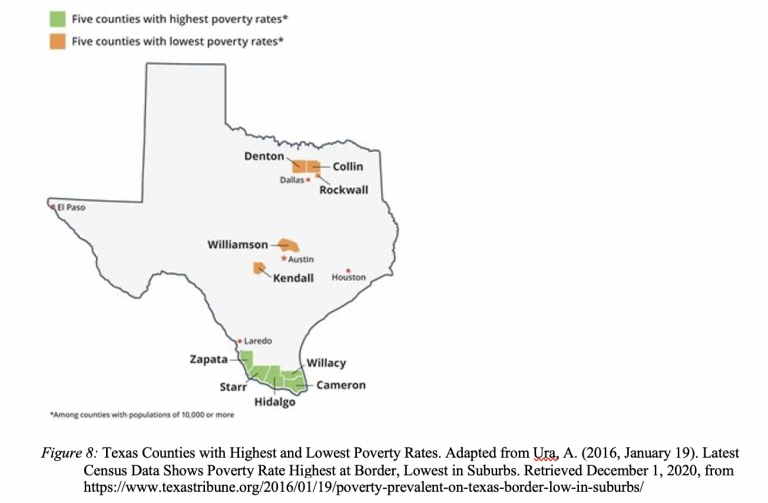

Cameron County is the southernmost county in Texas [see Figure 7]. It has a population of 423,163 with a median age of 32.4. [1] 90% of people in Cameron County are Hispanic or Latino, 23.5% are foreign-born, and 73.1% speak a language other than English at home. The median household income is $37,132 and 67.2% are high school graduates or higher.[2] Cameron County has the highest child poverty rate in the state of Texas with 47% of children living in poverty. [3] Cameron County is a part of a community of counties called the Rio Grande Valley. The five counties of the Rio Grande Valley, Cameron County, Hidalgo County, Starr County, Willacy County, and Zapata County, have the five highest poverty rates in the state [see Figure 8]. [4] The two largest cities in Cameron County are Brownsville and Harlingen.

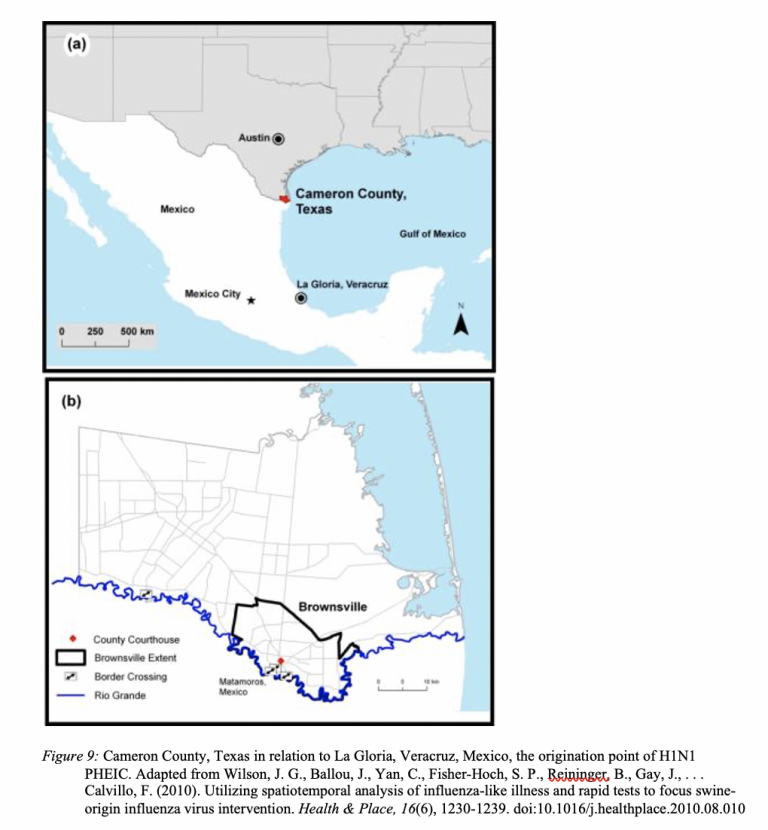

Cameron County, Texas was the second state in the U.S. to have documented cases of 2009 H1N1. [5] It is the closest geographic location in the U.S. to La Gloria, Veracruz, Mexico, the origination point of 2009 H1N1 [See Figure 9]. The epidemic influenza in Cameron County was detected only 5 weeks after the outbreak originated in Mexico. On April 24, 2009, Brownsville health clinics notified public health officials of 26 cases of influenza-like illness. The next day, the WHO declared H1N1 a PHEIC. By April 29th, an infant from Mexico City visiting family in Cameron County became the first H1N1 death in the U.S. On May 4, a pregnant woman in Cameron County because the first U.S. citizen to die from complications of H1N1 infection. In the first year of the virus, the CDC estimates that between 151,700 and 575,400 people worldwide died from H1N1. On August 10, 2010, the WHO declared an end to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, though the virus continues to circulate as a seasonal flu today. The first doses of the H1N1 vaccine were given in the U.S. on October 5, 2009. [6]

Cameron County began community level interventions utilizing bilingual promotoras, lay community health workers (CHWs) who went door-to-door fighting misinformation by educating county residents about prevention and treatment of influenzas. Additionally, newsletters discussing nonpharmaceutical interventions and avoidance of emergency rooms and outpatient clinics unless severely ill were widely distributed in the community. The promotoras were educated on answering H1N1 questions based on CDC fact sheets and they targeted large gatherings such as church events. [7]

Exact Cameron County 2009-2010 H1N1 vaccination rates are unclear. Historical evidence has shown that racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S., such as the largely Hispanic community of Cameron County, are at a greater risk for contracting both seasonal and pandemic influenza compared with White Americans. Despite the higher risk, minorities in the U.S. have seasonal influenza vaccination rates that are 15-18% lower than White Americans. These disparities highlight barriers to vaccination, negative attitudes towards vaccination, distrust of the medical system, and perceived risk of side effects. However, despite lower seasonal flu vaccination rates in minority communities, a 2011 study surveying people 18 years or older found no significant differences in 2009 H1N1 vaccination rates between White and Hispanic individuals (20.4% and 18.6% respectively).[8] There is clearly a disparity between Hispanic and White seasonal influenza vaccination rates, but this same disparity did not exist for H1N1 vaccination rates.

When Esmeralda Guajardo was first appointed Health Administrator of Cameron County in 2015, she was, “looking forward to putting Cameron County Public Health on the map.” [9] Just over one year later on November 28,2016, Cameron County experienced the first case of locally acquired Zika virus in the state of Texas and the second in the U.S. In 2016, Cameron County experienced 26 cases of Zika virus. [10]

The Cameron County Public Health Department utilized a number of public health interventions to address Zika virus. They went door-to-door to inform patients of Zika risks and to collect blood samples for testing. Similar to their actions during the H1N1 PHEIC, they also utilized the CHW promotoras for education on Zika transmission and symptoms. According to Guajardo, residents of Cameron County were incredibly responsive to suggested public health interventions aimed at reducing Zika cases because of the high trust between community members and the public health department. Misinformation during Zika virus was limited because the outbreak was well contained within Cameron County and reach and spread of misinformation was limited. [11]

Now with the COVID-19 PHEIC, Cameron County is again the center of a public health emergency in Texas. The county has had over 27,000 cases of COVID-19 with 1,146 deaths. [12] In the summer of 2020, Cameron County was leading the state of Texas in new cases of COVID-19 as well as case fatalities. Today, Cameron County is in the top ten counties with the most confirmed COVID-19 cases in Texas. [13]

The Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine should begin distribution in Cameron County in just a few weeks. [14] While the healthcare workers and high-risk populations will be prioritized to receive what limited supply is available, the vaccine will eventually be made available to the general public. Public health officials, including Esmeralda Guajardo, have been preparing to educate their communities about the COVID-19 vaccine and are prepared to address any hesitancy in order to ensure adequate vaccination rate. When this interview was conducted in October 2020, Guajardo was less concerned about COVID-19 vaccine rumors or conspiracy theories in Cameron County residents. Of greater concern to county residents were political pressures on the COVID-19 vaccination. [15] Cameron County is a majority democratic county in a Republican-led state and Republican-led federal government. The concern lies in the political pressure that led to the vaccine’s development and lack of trust in efficacy of the vaccine, given the speed that it was created and the leadership who oversaw its creation. It is important to note that these concerns were voiced prior to the U.S. presidential election in which Democratic challenger, Joe Biden, defeated Republican Donald Trump. It remains unclear if concerns of political pressure on the production of the COVID-19 vaccine are alleviated now that Joe Biden is set to take office.

The Cameron County Public Health Department is working on educational campaigns to promote the COVID-19 vaccine to both patients and providers. Guajardo has found that personal anecdotes are a powerful tool for behavior change and therefore plans to turn to community leaders, elected officials, superintendents, hospital administrators, and law enforcement, for help in public health campaigns. As a community leader, Guajardo plans to receive the vaccine publicly to build trust in its efficacy. In order to combat misinformation, Guajardo hopes to utilize mass media campaign to bombard the community with reliable, trusted information about the COVID-19 vaccine. As utilized in the H1N1 pandemic and Zika virus PHEICs, Cameron County will utilize the CHW promotoras to promote vaccine efficacy. [16]

The case study of vaccine hesitancy in Cameron County highlights a number of issues in public health emergency preparedness and response. First, greater emphasis must be placed on health equity for high-risk communities. Cameron County was the location of the first U.S. citizen death from H1N1 in the U.S., the second locally acquired case of Zika virus, and was the epicenter for COVID-19 in Texas in the summer of 2020. Despite being an obvious hotspot for public health emergencies, the county continues to be understudied. Regardless of the lack of analysis, the county’s public health department has been largely effective in communicating and working with county residents. The public health community could benefit from a deeper analysis of how the Cameron County Public Health Department maintains a positive and trusting relationship with the community.

A recurring piece of Cameron County’s successful response to public health emergencies are the CHW promotoras. Although no research has explicitly evaluated the promotoras in Cameron County, community health workers have been seen as effective resources for culturally specific sources of science-based information for health promotion. Many low-income countries have utilized CHWs as trusted members of the health system who can help bridge the gap between healthcare providers and patients. CHWs often represent target communities at highest risk. [17] Many health experts believe that CHWs would be instrumental members of the U.S. health system, however, the current system fails to provide CHWs recognition, status, job security, or benefits in line with their potential value. [18] CHWs are also in-line with the Emergency Decision-Making Framework as they are a widely trusted information source both by the community and the public health department that could be utilized to disseminate information and combat misinformation in PHEICs. CHWs like the promotoras in Cameron County could potentially be valuable resources for emergency response in areas that are most impacted by misinformation and vaccine hesitancy.

The U.S.-Mexico border is a dynamic region approximately 2000 miles long that requires individualized interventions and understanding. Border health presents unique challenges and opportunities that include a rapidly growing, young, and Hispanic population, low education attainment, low-income communities, high poverty rates, high rates of uninsured, and inadequate number of healthcare providers. [19] These are each considered the social determinants of health that impact access to quality and affordable health care. As stated by Esmeralda Guajardo, the U.S.-Mexico border is a two-way street with individuals constantly coming and going. The high traffic volume present particular challenges during PHEICs because of the difficulties the mobility poses to infectious disease surveillance, outbreak investigations, and interventions such as quarantines or contact tracing common in public health emergencies. [20] In order to better gain bargaining power against larger cities and municipalities, Guajardo created an association of border health officials along with other U.S. border county public health departments. [21] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has a binational U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission founded in 2000 that has two annual cooperative agreement activities: Border Health Month and Leaders Across Borders, an advanced leadership development program aimed at building binational leadership capacity of public health, healthcare, and other community professionals working on border health. [22] Activities and research promoting border health have been largely limited, despite the continued need for understanding of these complex communities.

Hispanic communities should be studied further to understand if a social and cultural norm is promoting or preventing their responsiveness to public health emergency interventions. Some researchers have speculated that because the H1N1 pandemic originated in Mexico, Hispanic communities either near Mexico or with high populations of Mexican residents might have had a heightened awareness for H1N1. Further, the H1N1 vaccine was given with no charge to patients which might have benefited the Hispanic community given previous research that they fact cost-related barriers to vaccination. [23] More analysis must be conducted to better understand predominantly Hispanic communities as well as border health and why they have been relatively responsive to public health interventions in times of emergency.

As indicated by the high H1N1 vaccination rates, high community responsiveness to public health intervention during Zika virus and COVID-19 PHEICs, Cameron County appears to be largely protected from misinformation-driven behavior change. It is possible that misinformation exists in Cameron County as much as any comparable county, however, the residents have not behaved in a manner contrary to public health recommendations. There is reason to believe that in Cameron County, a protective factor exists that is shielding the residents from the potentially devastating impacts of misinformation.

As a border health population, Cameron County is in need of greater funding for emergency preparedness and better research of emergency response in their community. The public health department lost 60% of its preparedness staff as well as three epidemiologists and national stockpile and immunization response coordinators due to the burnout caused by COVID-19 workload. [24] The County’s Public Health Department needs additional resources in order to more effectively do their job. Cameron County does not have a high-capacity lab and most COVID-19 tests have to be sent out of the county for analysis, leading to slower response. Cameron County-specific COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy data has not and likely will not be collected but could be vital in better understanding the community. Greater funding to formally study the resiliency and community trust of Cameron County and potentially other predominantly Hispanic, border communities would benefit country-wide public health emergency preparedness and response in combatting the rise of misinformation.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.