Tejan M. Part II: Vaccine hesitancy and misinformation. HPHR. 2021; 31.

DOI:10.54111/0001/EE4

As noted in Misinformation in Public Health Emergencies, health misinformation has far reaching and potentially damaging impacts on behavior. One example of a behavior change based on misinformation is vaccine hesitancy, a movement whose concerns been largely scientifically discredited but continue to spread through online communities. Misinformation and vaccine hesitancy are issues that the global community, both in the public and private sector are struggling to address.

The impacts of misinformation on health behaviors are best demonstrated by vaccine hesitancy data. In 2014, the U.S. had a large measles outbreak that was primarily attributed to parents seeing misinformation online and choosing not to vaccinate their children. [1] Measles was declared eradicated from the U.S in 2000 because of an effective vaccination program. [2] U.S. measles cases hit a record annual high in 2019 with 1,282 cases across 31 states, the most since 1992. [3] In fact, as recently as 2012, the U.S. had only 55 annual cases of measles. At a global scale, measles death toll in 2019 was 207,500, an increase of 50% than only three years earlier. [4] The rising cases of measles exemplify vaccine hesitancy, which is a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services. [5] Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context-specific, and is influenced by factors like complacency, convenience, and confidence. [6] Investment in vaccine education and public trust building as well as vaccine affordability and availability are being thwarted by the antivaccination movement. [7]

A driving factor of this phenomenon was a 1998 study in The Lancet, which claimed that the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine cased autism. This claim was immediately refuted and the study itself has since been retracted. However, the claim garnered popularity and is still referenced today by leading anti-vaccine groups. In 2019, the U.S. had multiple declaration of public health emergencies because of measles outbreaks. [8]

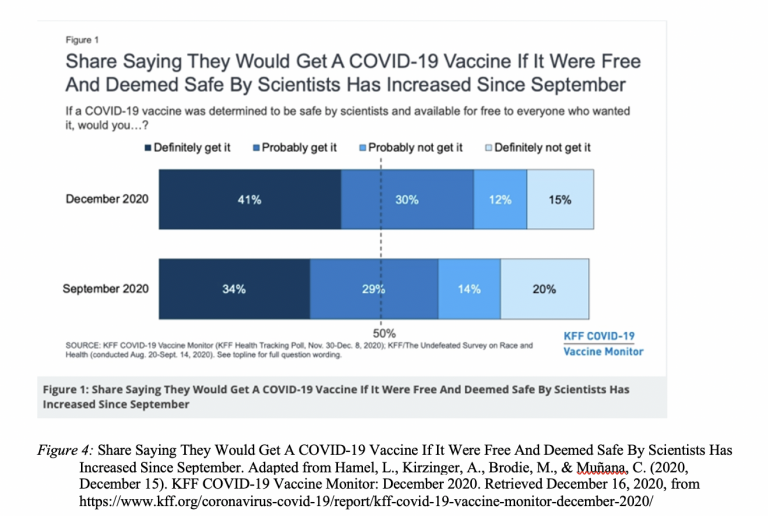

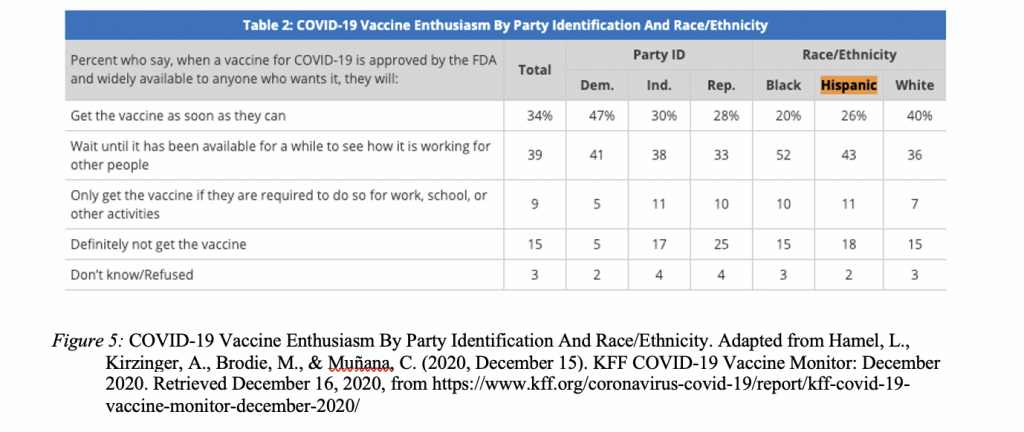

Now, vaccine hesitancy caused by misinformation is impacting public health response to the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Polling and survey data have indicated high rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy across the U.S. Early figures suggested that as many as two-thirds of Americans would not get the COVID-19 vaccine when it is first available with one in four saying they do not want to ever take the COVID-19 vaccine. [9] Further, early polls stated that Hispanic and Black participants are less willing than White participants to take the vaccine as soon as it is made available.[10] However, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Vaccine Monitor has found a gradual reduction in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, potentially due to U.S. presidential election and promising news on COVID-19 vaccine efficacy. KFF now finds that 71% of the public would definitely and probably get a COVID-19 vaccine if it is determined to be safe by scientists and available for free to everyone who wanted it, up from 63% in September [see Figure 4]. [11] Vaccine hesitancy is highest among Republicans, those ages 30-49, and rural residents. [12] According to KFF findings, only 26% of Hispanic individuals would get the vaccine as soon as they can, while 43% would wait until it has been available for a while to see how it is working for other people, 11% would only get the vaccine if they are required to do so for work, school or other activities, and 18% will definitely not get the vaccine. [13] This is in comparison with 40% of White individuals saying they would get the vaccine as soon as they can, 36% waiting until it has been available for a while to see how it is working for other people, 7% only getting the vaccine if they are required to do so for work, school or other activities, and 15% definitely not getting the vaccine [See Figure 5]. [14] The cultural differences in vaccine hesitancy stem from individual rights beliefs towards vaccination, various religious standpoints and vaccine objections, and suspicion and mistrust of vaccines among different communities. [15]

This hesitancy can at least partly be explained by widely spreading COVID-19 vaccine misinformation. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy misinformation has included claims that the COVID-19 vaccine would use microchips as a part of a global tracking system, that the COVID-19 vaccine would alter human DNA, that Dr. Anthony Fauci would personally profit from a COVID-19 vaccine, and that the COVID-19 vaccine trials did not use placebo for control groups. [16] This misinformation has direct effects on the behavior of those who believe it to act in a manner contrary to their best interests. An Annenberg Public Policy Center study found that only 72% of people who were most likely to believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories said that they wear a mask every day in public settings. These respondents were 2.2 times less likely than those who did not believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories to say they want to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Both mask wearing and the COVID-19 vaccine have been widely recommended to slow the spread of COVID-19.[17]

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.