Merchant A. Analysis of COVID-19 awareness among Georgia private high school students. HPHR. 2021; 27.

DOI:10.54111/0001/aa6

Throughout the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has updated the public on pertinent information regarding COVID-19 developments. However, individuals may also refer to other sources for information, potentially affecting their understanding of the illness. This study aimed to serve as a baseline reference for assessment of Georgia high school students’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on COVID-19. A hypothesis was developed to ascertain three trends: which COVID-19-learning resources were most commonly used by students, how students’ knowledge of COVID-19 would change over time, and how their understanding varied by grade level. An online survey with primarily multiple-choice and check-all-that-apply questions was distributed with 157 private school and 14 public school student respondents, testing them on COVID-19 prevention, treatment, transmission, and symptoms. The hypothesis for this study is that students primarily use non-CDC-affiliated social media to learn about COVID-19. Secondly, the hypothesis states that increasing media coverage of COVID-19 results in a trend of greater student understanding throughout the survey release. The hypothesis’ final component is that older students are generally more knowledgeable about public health threats than their younger peers. Based on the survey results, grade level did not affect knowledge of COVID-19, and students’ main learning resources were online news outlets, family members, and television networks. Although their understanding decreased over time, the changes were statistically insignificant. Respondents remained relatively knowledgeable about COVID-19 and communicated significant confidence in their outbreak-response capabilities. Their primary misunderstandings were of a face mask’s purpose and the length of interaction needed for transmission.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a type of coronavirus causing primarily respiratory-based infections as part of COVID-19 (National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, Division of Viral Disease [NCIRD, DVD], 2020c). For months, Georgia’s highest daily cases count was 1,598 on April 7th (Georgia Department of Public Health [GDPH] et al., 2020). This was first surpassed on June 20th with 1,800 cases followed by greater numbers heading into July (GDPH et al., 2020). Although expanded testing capacity partially accounts for the increased numbers, the state’s positivity rates from late May to early July exceeded the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended standard (COVID Tracking Project, 2020; Johns Hopkins University & Medicine: Coronavirus Resource Center, 2020). In late June, Governor Brian Kemp avoided establishing additional statewide regulations. (Bluestein et al., 2020). Additionally, on July 15th, Governor Kemp prohibited citywide mask mandates and discontinued all mandates established by local officials (Kemp, 2020b, section 8(e)). The statewide growth in cases and transmission further justifies why Georgians must remain knowledgeable about the virus and necessary precautions, including those not required by the state.

This awareness is also important considering the long timeline until herd immunity. Herd immunity occurs when a sufficient percentage of the public is immune to a pathogen, weakening transmission efficacy and protecting non-immune individuals from infection (Randolph & Barreiro, 2020). Two approaches exist to herd immunity, with or without vaccination, the latter of which could result in over thirty million deaths based on an estimated infection fatality rate of 0.6% and a reproductive number of three (Randolph & Barreiro, 2020). To avoid these deaths, the public can socially distance and follow guidelines to mitigate community-wide transmission before a vaccine is developed, distributed, and able to yield herd immunity.

Although the WHO and other groups are expediting the vaccine development process, current expectations predict early trials ending in the late-2020 to mid-2021 period (Koirala et al., 2020). Before these dates, students may return to in-person learning. Regardless of the measures taken by schools, the school year could bring about an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among students. To help students understand how to remain healthy without herd immunity, the CDC and other public health centers must determine where students are struggling in understanding COVID-19 and what media platforms are best suited for disseminating that information.

This study’s purpose was to identify trends at a stage in the pandemic when data regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of high school students on COVID-19 had yet to be obtained and data collection efforts became complicated by limited access to students due to statewide school closings. Additionally, this study’s goal was to conduct a formative evaluation to help explore initial trends that could serve as a foundation for subsequent analysis of high school students. I distributed an online survey to primarily private high school students across Georgia, asking respondents about COVID-19 and their main learning resources. In previous research, 82% of 12th graders and 83% of 10th graders reported nearly daily social media usage by 2016 (Twenge et al., 2019). Due to the link associating adolescents with significant social media usage, my hypothesis argued that non-CDC-affiliated social media were students’ primary learning resources. Assuming U.S. media coverage of COVID-19 would increase over time, my hypothesis claimed that students’ understanding would also increase over time. This assumption was validated by the U.S.’s Coronavirus Media Hype Index. On the first day of submissions, 03/13, 42.91% of news coverage concerned COVID-19 (RavenPack et al., 2020). On the last day, 04/27, the percentage reached 56.56% with notable peaks on 03/23, 03/30, and 04/06 (RavenPack et al., 2020). In terms of trends by grade level, my hypothesis was that older students would know more than their younger peers.

My survey responses indicated high school students primarily use online news outlets, television networks, and family members for COVID-19-related information. Additionally, student knowledge slightly decreased over time but remained within an average of 89-91% accuracy; no trends were found based on grade level.

The survey was designed from March 5th-March 13th using SurveyMonkey and distributed to students through faculty members and student leaders at various schools. An online, ten-question survey was deemed most efficient considering it was easily-accessible & disseminated by link without posing a public health risk. Due to the means by which the survey was disseminated, the proportion of responders among those who received the survey link cannot be accurately determined. Only the number of students who responded has been recorded. Respondents were informed of the survey’s purpose and their answers’ anonymity. No information was collected beyond students’ timestamp of submission and responses, including the type of school they attended and grade level.

The survey asked for the type of source students mainly used to learn about COVID-19 and whether their schools communicated any information to them regarding COVID-19. The graded portion was designed to reflect guidance from the CDC website as of March 6th. The first question was a select-all-that-apply type that assessed knowledge of COVID-19 preventative measures, requiring students to understand which measures were available at the time of submission and their purpose. The two other select-all-that-apply questions asked students to identify how SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted and primary COVID-19 symptoms. These questions required knowledge of COVID-19’s effects on the respiratory tract as well as the type and extent of exposure necessary for transmission. The only graded multiple-choice question analyzed whether students recognized how to seek external COVID-19 medical assistance and that healthcare facilities must take additional precautions before directly treating cases (NCIRD, DVD, 2020b). Lastly, respondents self-evaluated their outbreak-response capabilities with a five-point Likert scale and were allowed to provide additional comments.

In order to determine how student knowledge fluctuated over time, responses were divided by timestamp of submission and based on key points in Georgia’s COVID-19-response timeline. The first date range consisted of ninety-three responses, ninety-one of which followed the governor’s announcement of a public health state of emergency on March 14th (Governor Brian P. Kemp: Office of the Governor, 2020a). After the first date range, starting on March 24th, individuals more susceptible to COVID-19 complications had to shelter-in-place, and events with 10+ attendees required social distancing (Governor Brian P. Kemp: Office of the Governor, 2020b). An April 2nd executive order extended the shelter-in-place order to all Georgians, preceding the second date range (Kemp, 2020a, section 1(d)). In between these twenty-nine responses and the last date range of forty-nine responses was Governor Kemp’s announcement regarding the reopening of certain businesses (Governor Brian P. Kemp: Office of the Governor, 2020c). Responses were also split up by grade level and by primary COVID-19-learning sources. This data was used to determine which sources were most informative and whether grade level affected student knowledge. An average score was attributed to students under each date range, learning resource, and grade level; the tally of responses corresponding to students in each category was compiled into tables and figures for comparison.

The four scored questions were graded out of fourteen points. In the three select-all-that-apply questions, each selected correct answer and each unselected incorrect answer, other than “I don’t know,” received one point. In the multiple-choice question, the correct answer received one point while the incorrect choice received zero points. If “I don’t know” and at least one other answer was selected, the “I don’t know” was disregarded, and the question was graded normally. Other special cases were for students partially completing the survey. Although their answers were ungraded, they were included in the tally of responses. Lastly, in question #8, if a student included a symptom under “Other,” it did not contribute to their overall score.

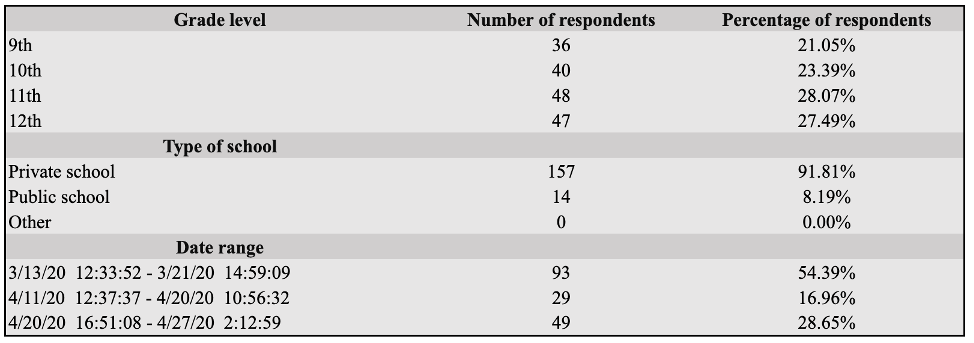

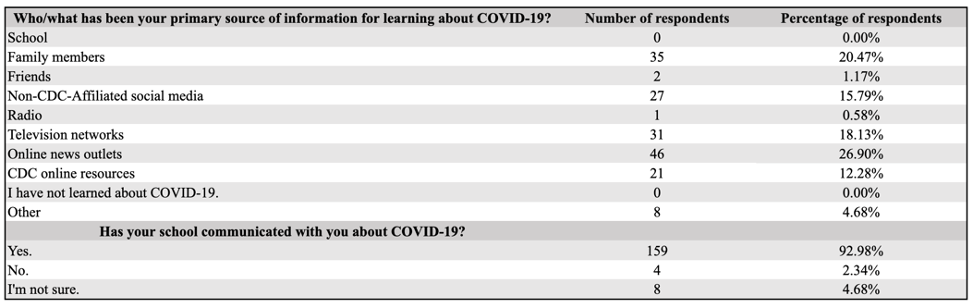

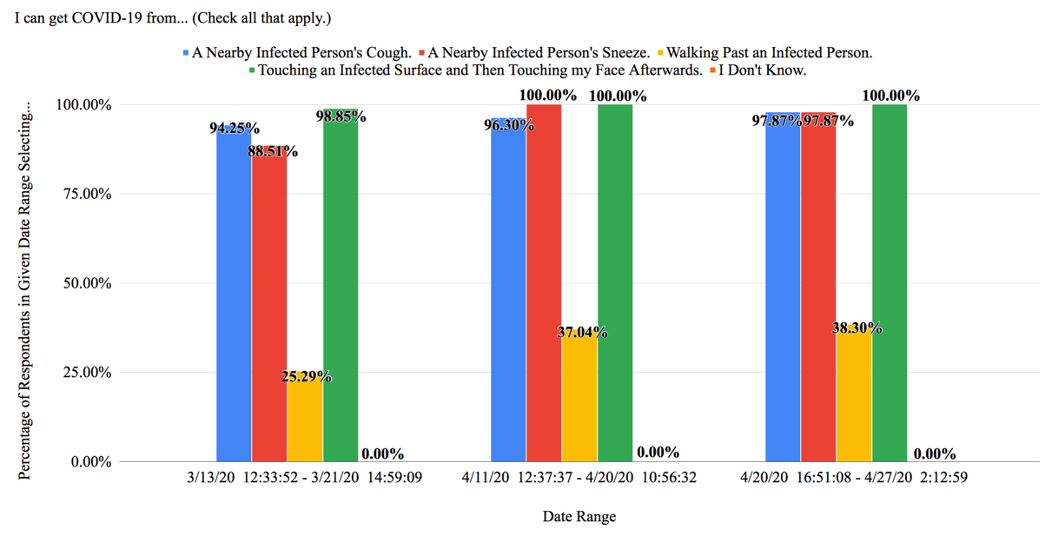

A relatively equal number of the 171 respondents belonged to each grade level, and 91.81% attended private schools (see Table 1). For this reason, no analysis was made regarding variation in knowledge between public and private school students. As shown in Table 2, contrary to the hypothesis, most students primarily referred to online news outlets, family members, and television networks to learn about COVID-19. Although no students used their schools as a primary resource, the majority of them received communication regarding COVID-19 from their schools.

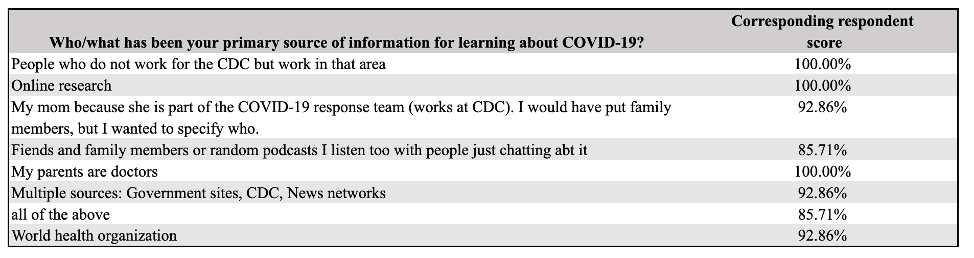

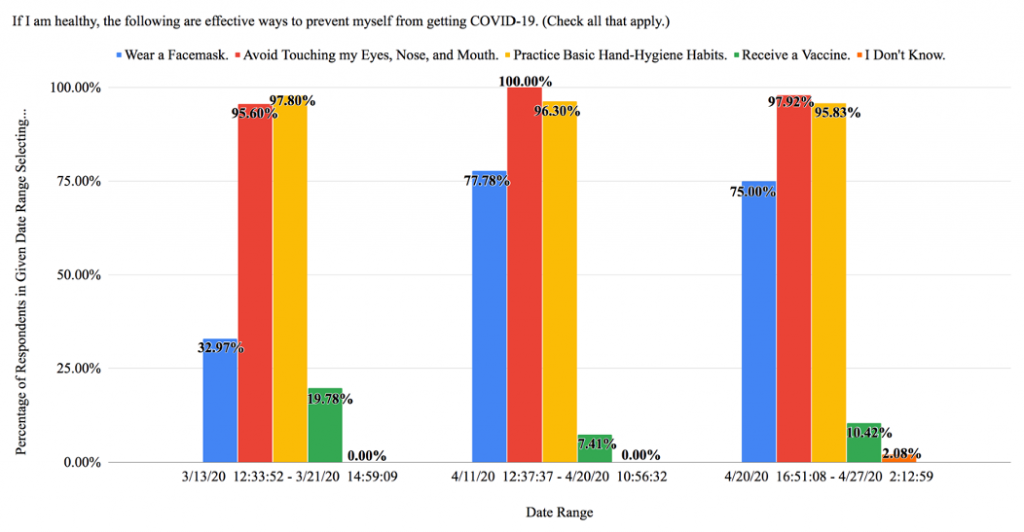

In response to question #5, the correct answer choices, “Avoid touching my eyes, nose, and mouth” and “Practice basic hand-hygiene habits,” were selected by at least 95.60% of students in each date range (see Figure 1). Although the percentage of students selecting the incorrect “Receive a vaccine” choice decreased after the first date range, the percentage of respondents incorrectly selecting “Wear a facemask” dramatically increased from 32.97% to 77.78% and 75.00%. For question #6, although nearly 9.00% of students in the first date range incorrectly chose to immediately visit their doctor without prior notice, 100.00% of respondents in the final date range selected the correct answer (see Figure 2).

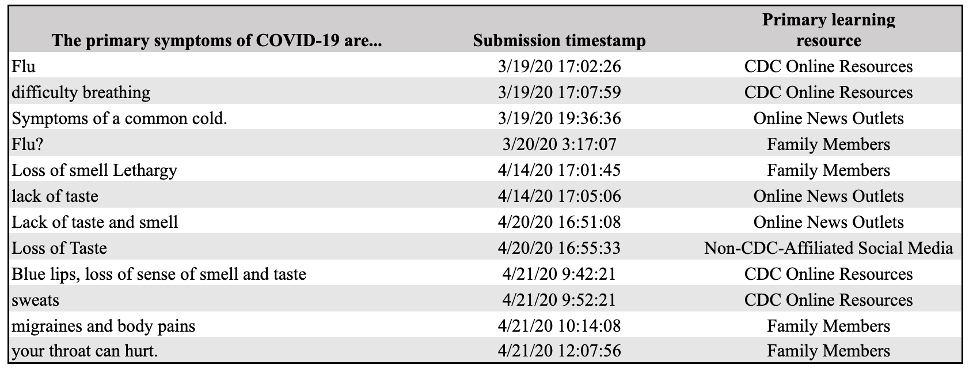

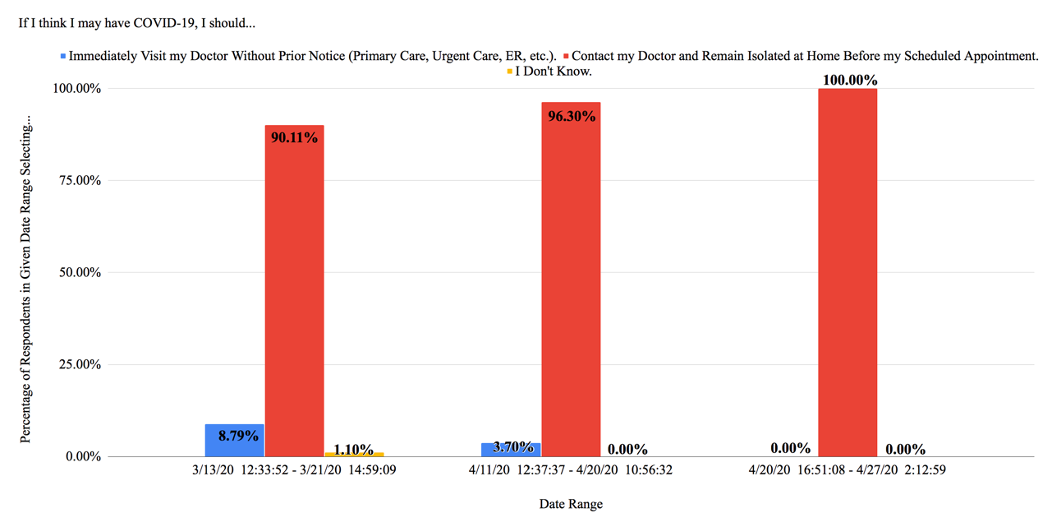

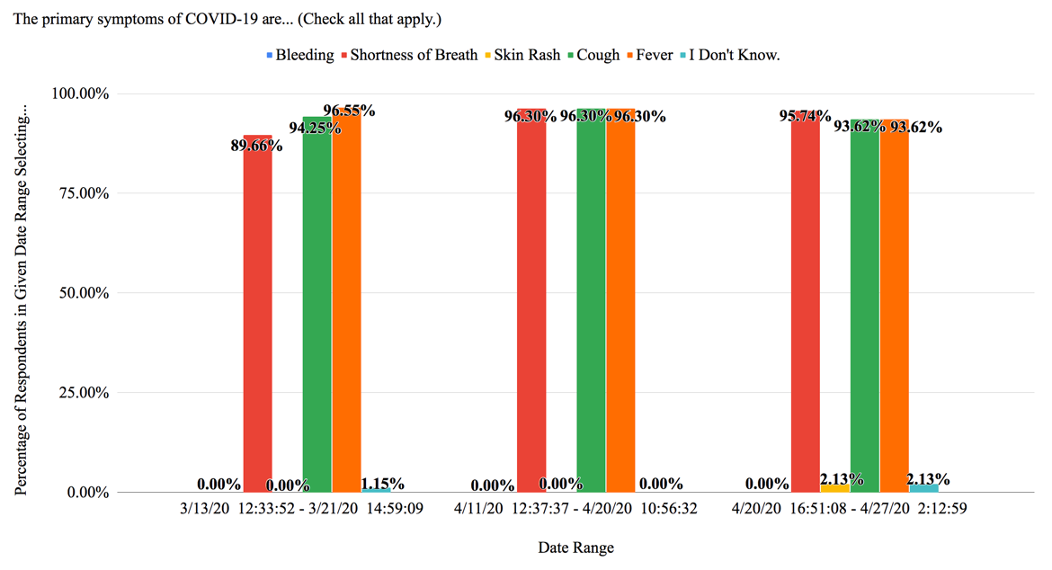

In response to question #7, an increasing percentage of students incorrectly chose “Walking past an infected person” (see Figure 3). However, the three correct answers were selected by at least 94.25% of students in each date range with an exception for “A nearby infected person’s sneeze” in the first. For question #8, only one student responded with an incorrect answer other than “I don’t know” (see Figure 4). Similar to question #7, excluding “Shortness of Breath” in the first date range, at least 93.62% of respondents chose the three correct answers within each date range. Twelve students also submitted responses for “Other,” many of which included loss of taste or smell (see Table 3).

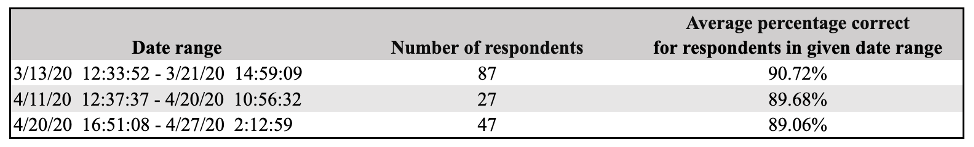

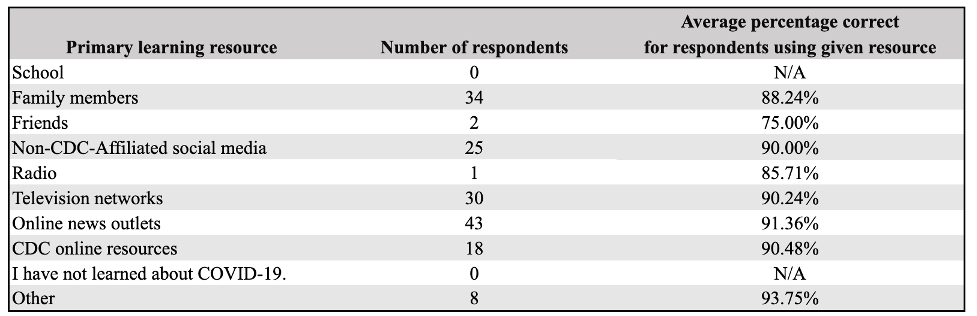

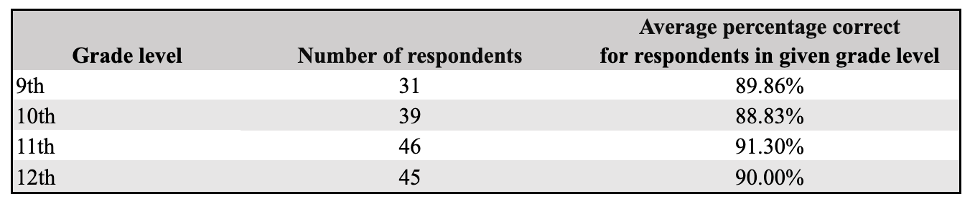

Students’ average score by date range slightly decreased over time from 90.72% to 89.68% to 89.06% (see Table 4). In terms of differences in awareness by learning resources, the poorest scores were from students using friends or the radio (see Table 5). If these scores were disregarded for their small sample size, students referring to their family members and non-CDC-affiliated social media scored the lowest averages. The highest average corresponded to students selecting “Other” as their primary learning resource. When the scores were divided by grade level, the range was 2.47% (see Table 6).

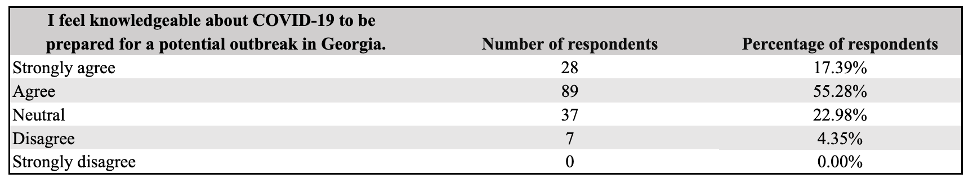

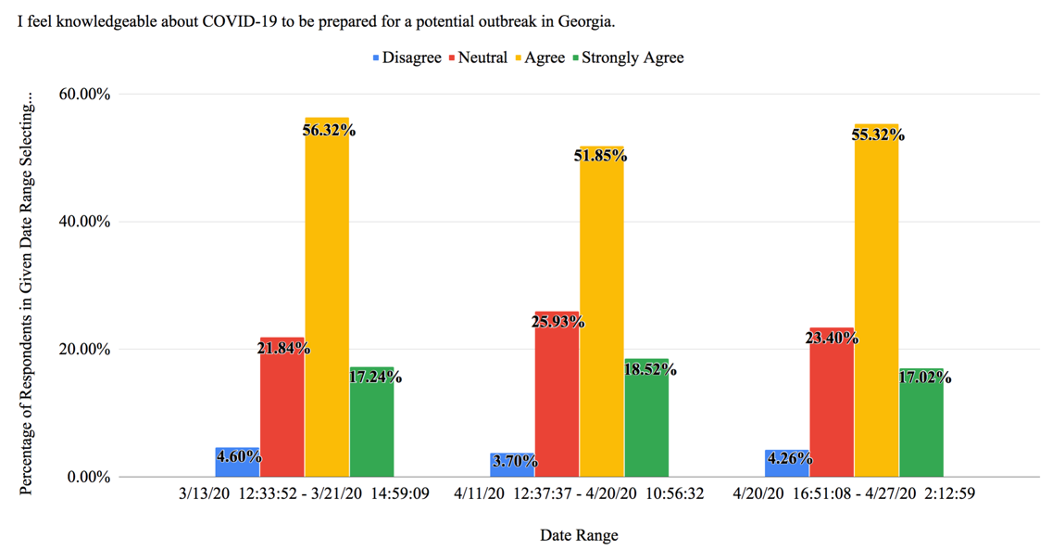

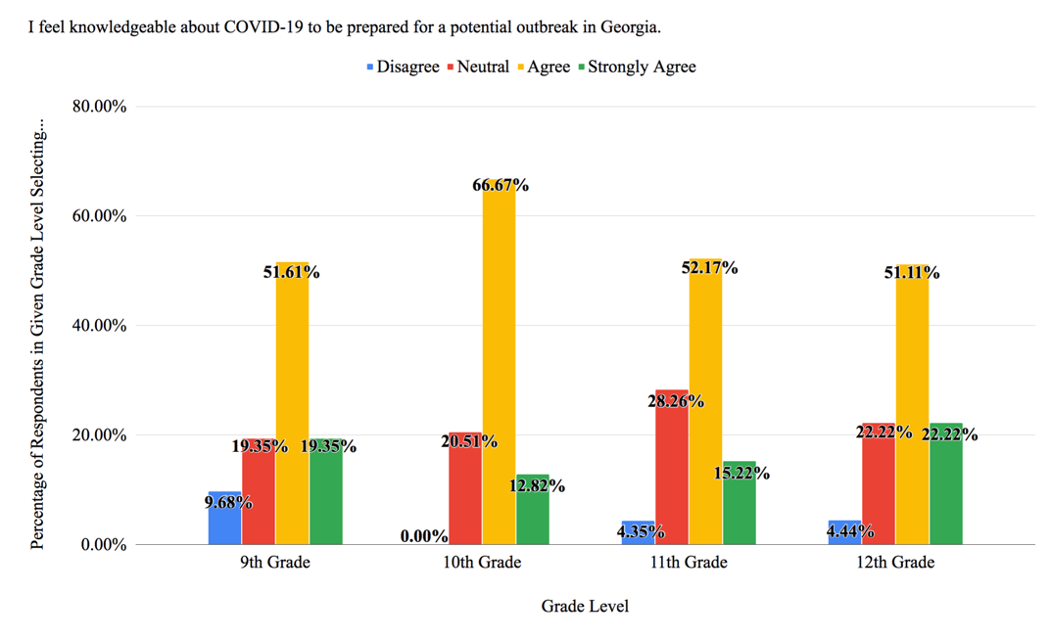

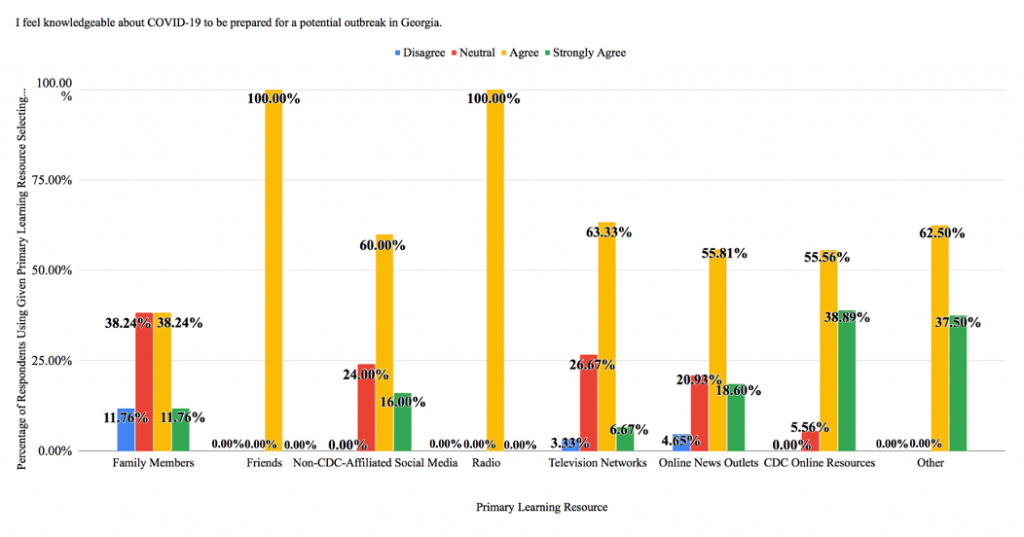

When self-evaluating their outbreak-response capabilities, most students selected “Agree” (55.28%) or “Neutral” (22.98%) (see Table 7). These choices remained most popular when categorized by submission timestamp (see Figure 5). Similarly, at least 51.11% of students in each grade level selected “Agree” while the second most popular choice was either “Neutral” or tied between “Neutral” and “Strongly Agree” (see Figure 6). The data regarding student confidence was similar when divided by learning resource (see Figure 7). “Agree” and “Neutral” were the most common responses for four of eight selected choices, and 100.00% of students using friends or the radio selected “Agree.” The two categories demonstrating the most confidence were “CDC Online Resources” and “Other,” where 94.45% and 100.00% of students respectively answered “Agree” or “Strongly Agree.”

Responses were evaluated based on guidance from the CDC website to avoid contradiction and ambiguity. The study’s main limitation is its small sample size, especially considering 8.19% of 171 respondents attended public schools. Since disparities may exist in access to COVID-19-learning resources between public and private high school students, the data may have differed if more public school students had been surveyed. The results therefore cannot be generalized to the entire Georgia high school population. However, the study fulfilled its intended purpose by collecting novel data regarding high school students’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on COVID-19, thereby serving as a baseline reference for future data collection efforts. If the study were to be repeated, a larger sample size should be obtained with students from a broader demographic to generalize identified trends to the greater Georgia student population.

A future survey should also provide additional choices under question #2 that account for friends and family members with varied expertise. The hypothesis incorrectly predicted the popularity of non-CDC-affiliated social media as learning resources. Based on the survey results alone, public health groups should communicate information to high school students through online news outlets and television networks, the first and third most popular COVID-19 news sources among students. Using such media also effectively targets adults, indirectly benefiting students by informing their family members, or the second most popular source (Mitchell et al., 2020).

In a repeated survey, question #5 should acknowledge that an individual must be tested to definitively know whether they are uninfected. For this question, an increasing percentage of students selected “Wear a facemask” following the CDC’s revised face covering guidelines on April 3rd (White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 2020). Face coverings are used to protect others and can combat unknown transmission from asymptomatic or presymptomatic cases. (NCIRD, DVD, 2020f). By selecting “Wear a facemask,” students demonstrated a misunderstanding of the reasoning behind the CDC’s face covering recommendation. Understanding this reasoning is essential considering the current politicization associated with face masks and their prevention capabilities. According to one model, without a face mask mandate between April 8th and May 15th in fifteen states and the District of Columbia, there could have been an additional 230,000-450,000 cases by May 22nd (Lyu & Wehby, 2020).

Some respondents also selected “Receive a vaccine” within each date range. While this possibly indicates unawareness of the vaccine development timeline, students may have thought the answer choice applied to the future. Receiving a vaccine may eventually be an effective measure against COVID-19; however, there is insufficient information regarding when a vaccine will be developed and implemented. A future survey should include a specific date attached to the “Receive a vaccine” choice.

For question #6, at least 90.11% of students in each date range selected the correct answer. Calling a medical facility before receiving COVID-19-related assistance provides healthcare workers with an environment that can mitigate transmission (NCIRD, DVD, 2020b). Transmission in the U.S. ‘s healthcare facilities roots back to late February; the first individual infected from community spread came into contact with 121 medical personnel at one hospital, forty-three of whom became symptomatic within fourteen days and three of whom tested positive (California Department of Public Health: Office of Public Affairs, 2020; Heinzerling et al., 2020). If the survey were to be repeated, the question should highlight that COVID-19 symptoms do not always require outside medical assistance (NCIRD, DVD, 2020b).

In response to question #7, the incorrect answer, “Walking past an infected person,” was increasingly selected from 25.29% of students in the first date range to 38.30% in the last. This may be due to extreme focus on the 6-feet social distancing standard and insufficient attention towards the time of exposure necessary for transmission, which is 15+ minutes according to the operational definition within the CDC’s Public health guidance for community-related exposure webpage (NCIRD, DVD, 2020d). Also, although the CDC notes surface-based transmission is less common, more students selected surface-based transmission than transmission by cough and sneeze during the first and third date ranges (NCIRD, DVD, 2020e.)

When answering question #8, one student incorrectly selected skin rash. Skin rashes like COVID toes have become increasingly common among COVID-19 cases, and the CDC notes that patients can experience symptoms beyond those within its official COVID-19 symptoms list (NCIRD, DVD, 2020c; Weill Cornell Medicine, 2020). However, since the CDC has not listed any skin rash as a primary symptom, skin rash was considered incorrect (NCIRD, DVD, 2020c). Scoring question #8 in this manner avoided penalizing respondents for being unaware of a symptom that the CDC has not formally associated COVID-19 with. Student responses largely aligned with the CDC’s first three listed symptoms, highlighting the list’s significant influence on public understanding of COVID-19 (Belluck, 2020).

Contrary to the hypothesis, students’ average scores by date range decreased over time, and 11th graders received the highest average score while the lowest belonged to 10th graders. None of these groups, by date range and grade level, did poorly with each average falling in between twelve and thirteen points out of fourteen. When the scores were divided by learning resources, students using the most popular choice, online news outlets, received the second highest average while those referring to the CDC’s online resources had the third highest average. However, variance between these average scores was minimal. Without respondents primarily using their friends, the range of average scores was a little over one point on the fourteen-point scale. The effectiveness of using friends for COVID-19-related information should not be discredited since only two of the 171 surveyed students did so.

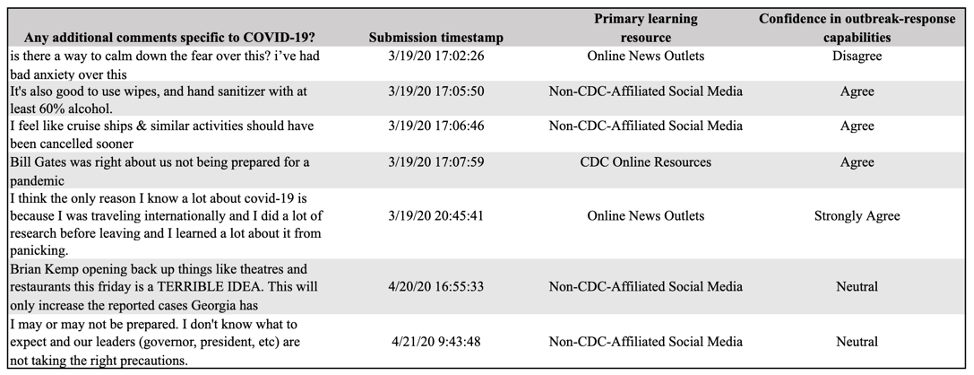

Many students were also confident in their outbreak-response capabilities. “Strongly Disagree” was never selected, and “Agree” was chosen by at least 51.11% of respondents corresponding to each date range, primary learning source, and grade level. The only exception was for students mainly referring to family members, where 38.24% of respondents selected “Agree” and another 38.24% selected “Neutral.” If a student was confident in their capabilities, they were not necessarily confident in the country overall. One student selecting “Agree” stated “Bill Gates was right about us not being prepared for a pandemic” (see Table 8).

Based on the survey results, students are relatively knowledgeable about COVID-19 and very confident in their outbreak-response capabilities. When assessed according to CDC guidelines, respondents increasingly misunderstood a face mask’s purpose and the time of exposure necessary for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The results also suggest that the CDC and other public health centers should update students on COVID-19 through online news outlets and television networks. Lastly, the CDC should cautiously develop its Coronavirus disease 2019: Symptoms webpage as most students only identified symptoms from this resource.

Table 1: Respondent Demographics by Grade Level, Type of High School, & Date Range (N = 171)

Table 2: Number & Percentage of Respondents Using Each Primary Learning Resource and Receiving COVID-19 Information From School (N = 171)

Table 3: Responses Submitted Under “Other” for Primary Symptoms Along With Respondents’ Corresponding Submission Timestamps & Primary Learning Resources

Table 4: Average Score for Respondents in Each Date Range (N = 161)

Table 5: Average Score for Respondents Using Each Primary Learning Resource (N = 161)

Table 6: Average Score for Respondents in Each Grade Level (N = 161)

Table 7: Student Confidence in Outbreak-Response Capabilities (N = 161)

Table 8: Select Additional Comments & Respondents’ Corresponding Submission Timestamps, Primary Learning Resources, and Confidence in Outbreak-Response Capabilities

Table 9: Responses Submitted Under “Other” for Primary Learning Resources & Respondents’ Corresponding Scores

Figure 1: Responses Divided by Date Range for Question #5: Prevention (N = 166)

Figure 2: Responses Divided by Date Range for Question #6: Treatment (N = 166)

Figure 3: Responses Divided by Date Range for Question #7: Transmission (N = 161)

Figure 4: Responses Divided by Date Range for Question #8: Symptoms (N = 161)

Figure 5: Student Confidence in Outbreak-Response Capabilities by Date Range (N = 161)

Figure 6: Student Confidence in Outbreak-Response Capabilities by Grade Level (N = 161)

Figure 7: Student Confidence in Outbreak-Response Capabilities by Primary Learning Resource (N = 161)

The resources needed to complete the study were provided by the Mount Vernon School’s Ricky Hyde. The Mount Vernon School’s Aaron Hawkins supported the author in the finalization of this article. The author would also like to acknowledge the help of CDC Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion’s Dr. Arjun Srinivasan.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Aqil A. Merchant, The Mount Vernon School, 510 Mount Vernon Hwy, Atlanta, GA 30328. Email: [email protected]

Aqil Merchant is a high school senior at the Mount Vernon School in Atlanta, Georgia. He writes, “I will be attending Harvard College in the fall and intend to concentrate in History and Science. My interests include evaluating the intricacies of global health and tackling public health challenges for systematically disadvantaged communities.”

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.