Despite striding progress in cancer research and care, lethality in lung cancer persists as the disease continues to evade control efforts nationwide. The prevalence of smoking, the leading risk factor for lung cancer, has declined dramatically over recent decades past.

Yet, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer mortality in the US, with an average 5-year surivival rate of 20%. In 2021, an estimated 235,760 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed, and almost 132,000 patients will die – a mortality toll greater than the next two leading cancers combined.

Like almost all health conditions, cancer diseases are especially sensitive to the determinants that commonly drive health disparities. In fact, about 37% of premature cancer deaths occur due to of health disparities arising from factors like SES and race.

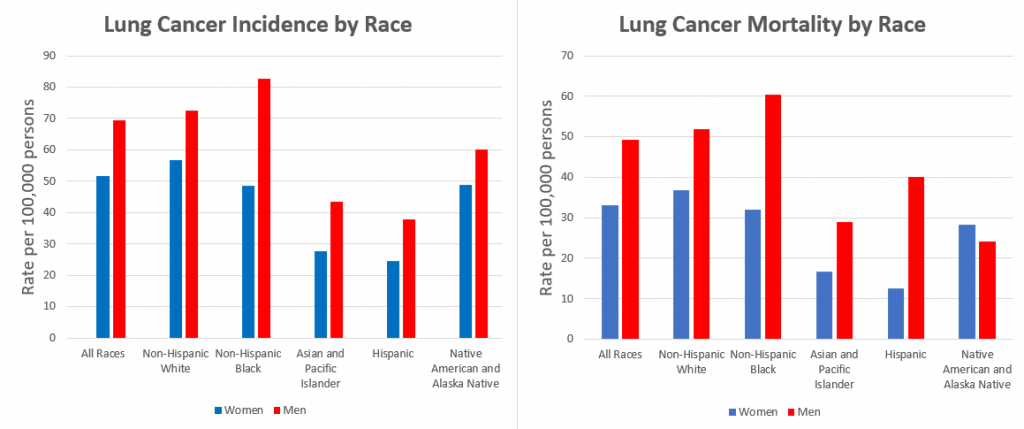

In lung cancer, disparities are most highly pronounced along lines of race, ethnicity, sex, and age. Black and Hawaiian Americans, as well as women, have an elevated risk of developing lung cancer at younger ages despite lower smoking intensity. Black men have the highest rate of lung cancer mortality of all populations, and lung cancer remains the leading cause of mortality in Hispanic Americans.

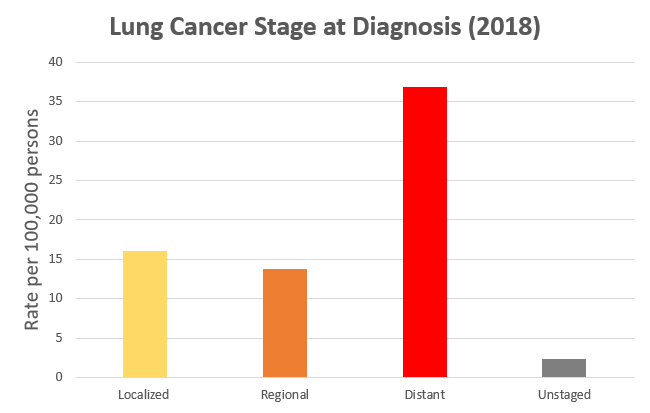

Unsurprisingly, the detection of lung cancer at early, localized stages significantly improves a patient’s chances of survival. In fact, the 5-year survival rate nearly triples from the overall average for early-stage patients (20% to 58%).

The prognosis for distant, late-stage disease is very poor, with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%. Yet, the vast majority of lung cancers continue to be diagnosed at advanced stages, especially among traditionally underserved minorities, contributing towards the persistent high mortality from the disease.

Now, you might be thinking that the only logical way to explain this data is that we simply do not yet have the ability to detect lung cancer at its early stages. You would be wrong.

Since 2010, multiple randomized trials (NLST, NELSON, etc.) have proven low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) as a highly effective tool to detect lung cancers in high-risk adults, showing a greater detection ability and strong mortality benefit compared to screening using chest x-rays (the previous standard-of-care).

In 2013, the United States Preventive Services Task Force enacted the first national recommendation for the use of preventive LDCT lung cancer screening (LCS) in Americans aged 55 to 80 who currently or formerly smoked with a 30 pack-year history (# packs/day × # years).

The intent of this recommendation was to reduce the high mortality rate of lung cancer by increasing detection of the disease at its earliest, most curable stages. Yet, the persistently high mortality trends discussed above and continuing patterns in diagnosis data don’t really tell a story of success.

Earlier this year in March, the USPSTF made a sweeping expansion to the US population eligible for LDCT LCS by lowering the minimum screening age by 5 years and reducing smoking history requirement to a 20 pack-year history. This new recommendation is estimated to skyrocket the number of screening-eligible adults from 6.4 to 14.5 million Americans across the country.

Indeed, eligibility expansion was a necessary and long-sought step in supporting screening. But inappropriate ineligibility among patients in need hasn’t been our biggest issue. Our greatest failure has been our inability to actually get people screened.

Since 2013, LCS has been seriously underutilized across the country, and things haven’t seen much improvement over a near-decade. In 2015, an NHIS review found that just 3.3% of eligible adults were getting screened. A more recent analysis of 2018 BRFSS data reported a 14.4% screening rate in 10 states.

If such abysmal screening rates were commonplace under the more conservative 2013 eligibility guidelines, imagine how low we could see screening rates plummet among the now more-than-doubled number of Americans that should be getting screened!

Even more pressing than the issue of low overall uptake, however, are the deep disparities in screening rates that have persisted along racial and socioeconomic lines. Even when eligible, underserved populations such as Black Americans and patients of lower household income have been demonstrated by several studies to be the least likely to be screened, largely due to disparities in access to care and the social determinants of health.

It is easily imagined, how such failures and disparities at the screening level would act to exacerbate the serious health disparities that already exist in lung cancer.

In order to drive down the toll of lung cancer, it must be more widely recognized that identifying the disease early is just as important as studying its biology or how best to treat it at advanced stages.

Pushing for more effective and more equitable LCS nationwide remains our most critical opportunity to address high mortality and health disparities in lung cancer.

As students and future leaders in public health, we must advocate for further work to be done to ensure that LCS can fulfill its potential as a truly transformative, life-saving intervention.

In future blog posts, I will investigate the complex challenges that have hindered effective and equitable lung cancer screening, and synthesize evidence-based strategies to guide our path forward in the fight against cancer and health disparity.

More from Brian Shim here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.