The i-value

By Javaid Iqbal

Health Care in Kashmir

*All authors contributed equally to this publication (Rofadun Nisa and Javaid Iqbal)

The weight of delivering health care during a pandemic is heavy—it is even more so when this is happening in a society suffering from a protracted socio-political conflict for the last seven decades. This is the reality of a valley nestled in the lap of the great Himalayas: Kashmir.

Since early 2020, the human and structural infrastructure in the valley of Kashmir has been under unimaginable stress, yet the frontline healthcare providers have answered the call of duty without fail. According to the Physicians Foundation, doctors, on average, should see 20 patients per day and spend at least 20 mins per patient. This is because spending time with the patient enables the doctor to build rapport and investigate the cause of the disease. In Kashmir, however, doctors usually have to take care of more than 150 patients in an Outpatient Department (OPD) per day. In addition, doctors have to work up the patients admitted for elective surgery and take care of both admitted and emergency patients concurrently.

The ongoing pandemic has exposed the flaws in Kashmir’s healthcare system, with deficiencies in both healthcare availability and delivery. A 2016 survey published by Doctors Without Borders (MSF) reported that 45% of the Kashmiri population had experienced some form of mental distress, with only 6.4% of the people with a mental illness ever visiting a psychiatrist.

Since 2019 Kashmir has been under a spate of curfews and lockdowns, first due to the revocation of Article 370 and now due to the Coronavirus. This has adversely affected the mental health of the general population—especially the youth. Nearly all mental health services are clustered in the capital city of Srinagar, which makes them inaccessible to patients in rural areas, with COVID intensifying these challenges. Up to 500 suicide cases have been registered in the last year alone. These trends have not spared the children: between 2016-2019, those treated for mental issues has risen from approximately 17000 to 30000.

Public Health care institutions in Kashmir deliver care to almost 97% of the population even though they are severely understaffed. The doctor-patient ratio is one of the lowest in India. The World Health Organization recommends one doctor for every thousand patients; Kashmir has a doctor-patient ratio of 1:2000. The valley has 2,459 oxygen-supported beds, only 752 of which could handle high-risk patients. There are only six hospital beds available for every 10,000 patients.

This lack of infrastructure is particularly hard on the nomadic Gujjar and Bakerwal communities which constitute 20% of the population. Patients from rural regions are directed to urban tertiary care facilities, losing valuable time in the commute, and sometimes even resulting in loss of life. Many hospitals, even at the district level, lack basic facilities such as having a blood bank. Due to the severe shortage of facilities in government hospitals, many families must seek healthcare from private hospitals and pay out-of-pocket (OOP). The private hospitals currently in operation are too expensive for the general population. As a result, many middle-class families get bankrupt while trying to keep their loved ones alive.

Multiple women can be seen sharing one bed in Srinagar’s main maternal hospital, called Lal Ded. 60% of married women in Jammu and Kashmir have reported at least one reproductive health problem, which is the highest in the country, with 26% of the pregnant women in a tertiary care hospital suffering from a depressive disorder. Studies at the valley premier hospital, the Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), report that 15.7% of women cannot have children without medical intervention. An additional 14% are incapable of conceiving due to other medical conditions.

There is also a high prevalence of C-section surgery among women in Kashmir. Due to the financial incentive of performing a C-section, many doctors continue to perform it even when not needed. This method of delivering is known to cause several socioeconomic, psychological, and health problems. According to Lancet the use of Caesarean section has risen over the past 30 years around 10–15% in developing countries without significant maternal or perinatal benefits. In addition, the technique is associated with short and long-term health effects and healthcare costs, resulting in severe mortality among women and children. According to the French Research Institute Development (IRD), India documented a yearly excess of 18 lakh cesarean childbirths from 2010 through 2016.

Lack of respect and mistreatment of women in public hospitals and needless interventional procedures in private facilities is common. Telangana which had the highest rates of cesarean births in the country has decided to professionally train midwives to improve maternal and infant care. According to WHO data, 83% of pregnancy and childbirth-related deaths can be avoided if midwives are involved. There is growing evidence that midwives are as good as doctors in taking care of pregnant women.

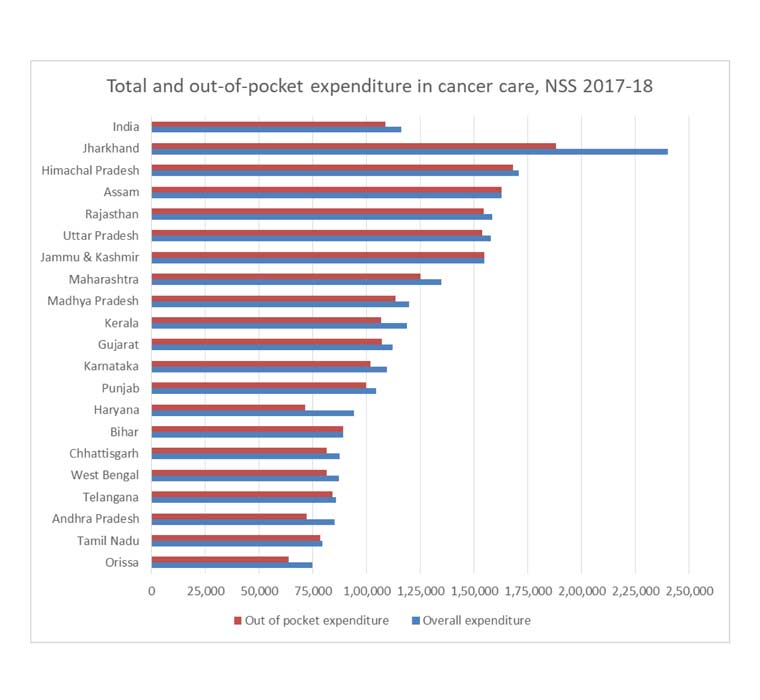

The number of cancer cases has also increased up to 87% since 2011—reportedly due to lifestyle changes. These trends in incidence are particularly worrying for breast cancer: women in Kashmir are mostly diagnosed at an advanced stage, resulting in a poor prognosis. In Jammu & Kashmir, most cancer expenses were met with high out-of-pocket expenses. Health costs also keep people poor and push those just above the poverty line back into poverty.

It is challenging to increase the quality and access to healthcare due to the lack of reliable data in Kashmir. However, the abrupt shift in the profile of diseases in Kashmir makes it urgent for the administration to improve programs that will improve healthcare in Kashmir.

*Dr. Rofadun Nisa is a Senior Resident in Ophthalmology at Government Medical College Srinagar Kashmir.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/dr-rofadun-nisa

Like what you read?

More from Javaid Iqbal here.