If you have thought about making art, here is a big endorsement: it’s healthy for you and the world. The product doesn’t have to look pretty. Besides, much of so-called high art closely resembles toddler art. As doors remain closed to traditional live performance and protest signs capture our place in history, now seems like the ideal moment to reconsider the how and why of art.

Let’s start with a simple question.

How do you define art?

Nothing…

I’m still waiting.

It’s okay if you’re stuck on museum painting. Three act play? Something fancy? Most art is hard to define with words. I kind of like that. No amount of market driven sales, trends, or other-people’s values should cage the scope of what art can be. Think freedom of speech that’s language based and beyond…

Art is merely a reflection of our way of life. With chosen tools, there is an intent to communicate and there is an outcome. Art frames the world. Photographs display byte sizes of the universe. Classic trilogies span continents. Sound effects surface the natural and inanimate energy in between. Art captures the stuff that matters and the fluff that surrounds it.

Mindful Art frames the world just the way it is. This type of art might showcase stuff otherwise overlooked had artists not presented it. I’m talking about the point of view of toddlers or voices of dissent. Think of Peppa Pig’s muddy puddle fetish. Check out the brilliant line, “our art is our reality,” in Straight Outta Compton. That stuff matters too, even if history textbooks rarely spotlight it.

I’m grateful artists have gone there, serving us the underbelly, the preverbal impressions, asking audiences to stretch or twitch or act foolishly. Artistry is the constant. Yet, every artist has a unique angle informed by what they are aware of and how they express themselves. When we are aware and expressive, I refer to this as Mindful Art.

As a self-defined Mindful Artist, philosophy rather than color palette threads my portfolio together: compassionate to self, other, and the planet; highlighting things as they situate, rather than striving for an ideal; honoring the margins, left out of the box yet right on the mark.

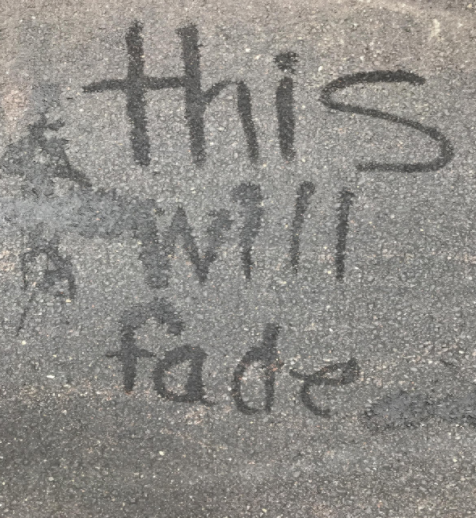

Here’s an example of my work, featured on my driveway for twenty-minutes, two years ago:

Some pitch art with the intention to someday be featured by The New York Times Style Section. I’m not dismissing that lofty goal. Sign me up. But then, their product becomes the next big trend. Maybe they are sought after and replicated, then mass produced. Mindful Art is an entirely different experience. Mindful art is the aesthetic of people, places, and things, precisely as they situate. Think Jean-Michel Basquiat’s graffiti across Lower Manhattan before he was referred to by last name only: Basquiat.

When I permit myself to pause long enough (from heavy days, these pandemic and acute-culture-clash days, as a psychotherapist in traditional health care), I acknowledge more beauty than not. I change the channel from the static that average twenty-first century standards perpetuate. I choose to pause. My favorite mode is art making. Such a powerful word, too often overlooked during these tumultuous times: pause. Pausing feels almost as out-of-grasp as art making. But I wish to challenge that belief.

“Pause, it’s a verb,” I like to tell my clients.

Tara Brach explains in her motivational masterpiece, Radical Acceptance, “In a pause, we simply discontinue whatever we are doing—thinking, talking, walking, writing, planning, worrying, eating— and become wholeheartedly present, attentive, and often physically still” (p.51). Demands, arbitrary expectations, and clutter swirl around us. Behind us, people may judge. Before us, some fear hangs heavy. And over there, that’s something we shoulda-coulda known if only we woulda remembered. Because of our biochemistry, we often crave the familiar over the healthy. Pausing might not be the automatic choice these days, and yet, it might be the most critical option we have.

We don’t have to enter an hour-long meditation to pause.

Yeah, who has time for that (even though we all could benefit)?

Have thirty seconds to spare?

Then, you have enough time to pause.

And inspire art making.

Join me. Find a tilted frame. Nearby, there is probably one. Don’t you dare straighten it. Don’t. You. Dare! Notice the frame. Honor how it situates, just as it is. Belief systems, memories, and lessons from someone else’s value system may have told you to straighten the frame. Please, do not react to those impulses.

Pause with me.

Let the frame be.

Instead, look a bit closer. Pay attention to the details, and perhaps a thing of beauty appears, otherwise missed in a moment of fix-it fixation. Pause a bit longer. Let the noted details be inspiration for letting go and showing up to a new moment with a Beginner’s Mind.

In Mindfulness, a way of maximizing the present moment’s influence by quieting the volume on past ideas or future dilemmas, we find a philosophy that trickles throughout world religions and sprinkles itself across spirituality. When we are in a Beginner’s Mind, we let go of preconceived thoughts, feelings, and sensations. We do not cling to previous circumstances or biases. We anchor in the sensory experience of now: sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound. Mindful art brews from a Beginner’s Mind.

I have found solace in tilted frames, a Beginner’s Mind, and Mindful Art making. Honoring the way things are, rather than should be, a healing process emerges based on authenticity. This healing extends to those I engage with through art and therapy; both, of the contemplative and not-easily-defined.

A few years ago, I organized a Mindful Art making group and titled it, “Reframe Your Artistry.” We evolved, transforming ordinary nature or objects into something at which to marvel. We repurposed non-recyclables and prioritized our share time as a nonjudgmental space to exchange ideas. The group took place, in the flesh, in a room no larger than what some would consider bathroom size. We placed materials upon an elephant decorated fabric from Thailand that previously served as a means for privacy when I provided therapy in homeless shelters. Crossing our legs around the fabric, we passed about materials and tips. With accessible items like dried flowers, toilet paper rolls, or scrap-paper, I wanted to create a safe space through art and allow art to begin a conversation for self plus community growth.

My office sits along a business strip of yogis, foodies, and healers. The group was offered to the entire community, a spot in Pennsylvania that intersects White suburban sprawl with a predominantly Black and Hispanic rural enclave west (way socially west of) Philadelphia’s Main Line. Only tweens and teens showed up. I refuse to call them kids. They’d find that demeaning, I suppose. Instead, I call them the Next Gen.

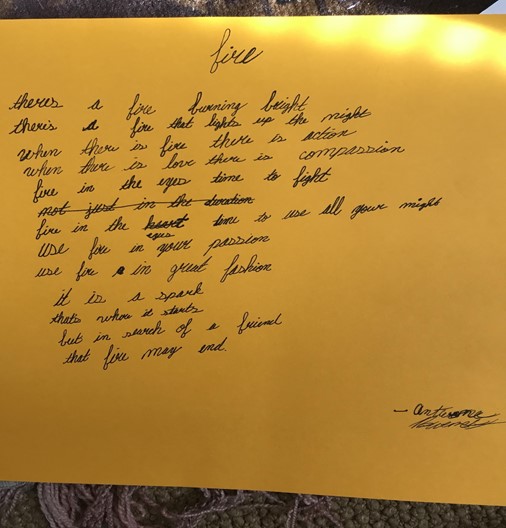

The last meeting before the pandemic hit, Antwone shared a poem. He asked that I feature it on the platform’s blog without typing it up. I said, “you’re an inspiration, a truly Mindful Artist.” We should all be struck by his authentic voice and his appreciation for something important, framed just as it situates.

Jessica Quinn Honig (they/them; she/her) resides in the Philadelphia region, practicing clinical social work at the micro, mesa, and macro level. She holds a graduate degree in Arts in Education from Harvard University, a social work degree from Smith College, and an undergraduate degree from Bryn Mawr College. At the micro level, she is a therapist and life coach with a passion for helping others face barriers related to Complex Post Traumatic Stress from lived experiences of chronic oppression and systemic ‘isms. She has also coined and treats Art Anxiety, as discussed in her 2019 book: Reframe Your Artistry, Mindful Tools for Art Making at Any Age. At the mesa level, Honig facilitates workshops to engage community in cross-cultural and intergenerational dialogue inspired by art making, repurposing non-recyclables, and the natural landscape. At the macro level, Honig wishes to grow her voice as a writer for survivors of complex trauma, psychoeducate on the often overlooked individual and sociological impact of complex trauma, as well as inspire future generations to live simply and compassionately while thinking critically about social constructions. To the latter point’s end – she is a curriculum designer and guest lecturer on Empathy in Design, for the Azusa Pacific University Graduate Program in UX/User Experience and she is Art Editor of the Pennsylvania Society for Clinical Social Work’s Journal – The Clinical Voice.

This blog originally appeared on HPHRxHealth Righters.org, an online collaboration of the Harvard Public Health Review, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Health Righters.

Health Righters is a multidisciplinary publication exploring the intersection of healthcare and human rights, led in part by Harvard College.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.