Welcome to my blog on “Advancing Black Feminism in Public Health.” My goal is to move black feminism from the margins to the center of public health by applying 10 key principles as legitimate and comprehensive frameworks for adequately addressing health threats and related social and structural determinants of health in the lives of black women and girls.

Dr. Quinn M. Gentry

In this blog, I highlight the significance of principle no. 4 (of 10): Engage Women in Multiple Settings to Address Unique Experiences for advancing black feminism in public health. Among the many unique experiences that set black women apart is the unfortunate intersection of enslavement and rape, while attempting loving relationships with enslaved men. This trauma manifests in modern day as economic exploitation of black women’s reproductive health, and the continued politicization of black women’s love relationships. These traumatic experiences have shaped generations of black women’s sexual health vulnerabilities, beliefs, and behaviors. However, diverse coping mechanisms among black women necessitates further analysis to understand and identify appropriate implications and interventions in physical, mental, sexual, reproductive, and maternal health.

“We must ‘level- up’ public health interventions and engage women in dynamic and different settings to maximize opportunities to optimize health."

Dr. Quinn, Intellectual Influencer Tweet

Public health approaches to addressing black women’s unique, traumatic sexual and violent histories can be empowering or oppressing.

Opportunities for empowerment and authentic engagement is linked to selecting the most appropriate interventions for diverse sub-groups of black women and girls. For example, discussing HIV/AIDS in a group setting among peers may not feel safe for some girls to freely engage in conversations about sexuality and sexual risk-taking. Furthermore, if she has been sexually molested, exploited, or raped, she may shut down altogether in a group setting. In both scenarios, program participants might benefit from one-on-one sessions prior to or intertwined with group sessions.

Closely related, women experiencing intimate partner turmoil or violence may be prohibited by partners from attending women’s health events. Still, other women may opt out of some interventions based on the social construction of stigma and bias towards public discussions of sexual health. These latter examples justify community, medical, and structural interventions as paramount to reach vulnerable women typically out of reach of traditional public health initiatives.

In blog 1, I introduced principle 1 (Respect Individuals’ Right to Self-Definition/Self Valuation) for advancing black feminism in public health. Succinctly, I highlighted how ethnographic interviews and direct observations of sex workers engaging middle class married men raised my consciousness about HIV risks among unsuspecting middle-class black women. In blog 2 (principle 2 on addressing controlling images), I elaborated on my dilemma of identifying appropriate levels of intervention for suburban black women who perceived themselves to be in monogamous heterosexual relationships. Initially, I faced some backlash about the purpose and intent of “raising issues that needed to be addressed as private matters”, which was a recurring response primarily from black women- and girls-serving organizations’ gatekeepers, whose own biases about sex and sexuality blocked access to larger groups of black women and girls. Engaging these leaders with a spirit of cultural humility resulted in aggregable strategies for including “mainstream black women” into evidence-based sexual health discussions under the theme of “healthy intimate partner relationships.” A glimpse of my approach to creative collaborations is highlighted below in practical point 3 for addressing unique experiences.

I selected frameworks applicable to a sociological perspective in public health conducive for connecting “the general and the particular” in operationalizing principle 4: Engaging Women in Multiple Settings to Address Unique Experiences. Each theoretical and research paradigm summarized below prioritizes unique experiences as core to addressing broader public health issues.

It is not enough to study black women because they are invisible. Rather it is incumbent that we examine and interpret their experiences.

Dr. Darlene Clark Hine Tweet

In this quote, Dr. Hine is challenging scholars to humanize their research on black women. In accepting this challenge, I adapted evidence-informed interventions on sexual risks to be less stigmatizing and more inclusive of elements comprising “healthy relationships”. This led to opportunities to engage unique sub-groups of black women and girls through partnerships with diverse black women- and girls-serving organizations, including churches, community, civic, and collegiate settings. While the content of these engagements remained science-based, the delivery included music from different genres and generations, about various phases of love relationships.

I have added the links to some songs I used for this community-level approach; however please note that I deconstruct song lyrics as ‘teachable moments’ to address unequal gender norms and roles, toxic aspects of relationships, and best practices in healthy relationships. I acknowledge that these songs are “old-school”. As you peruse my playlist, recall that this collaborative strategy was implemented between 2007 – 2017, and the goal was to engage intergenerational audiences. While the songs resonated with those 30 and up, a common practice was to ask younger participants for song suggestions to fit various relationship stages and improvise a discussion around an audience-driven playlist.

THE CONNECTION STAGE

You Don’t Know My Name (Alicia Keys)

If I Were Your Woman (Gladys Knight & The Pips)

Dilemma (Nelly ft. Kelly Rowland)

THE COURTSHIP STAGE

How Will I Know (Whitney Houston)

THE COMMITMENT STAGE

THE CONFLICT STAGE

Bust Your Windows (Jazmine Sullivan)

THE COMPROMISE STAGE

And I am Telling you I’m not Going (Jennifer Holiday)

THE CONCLUSION STAGE

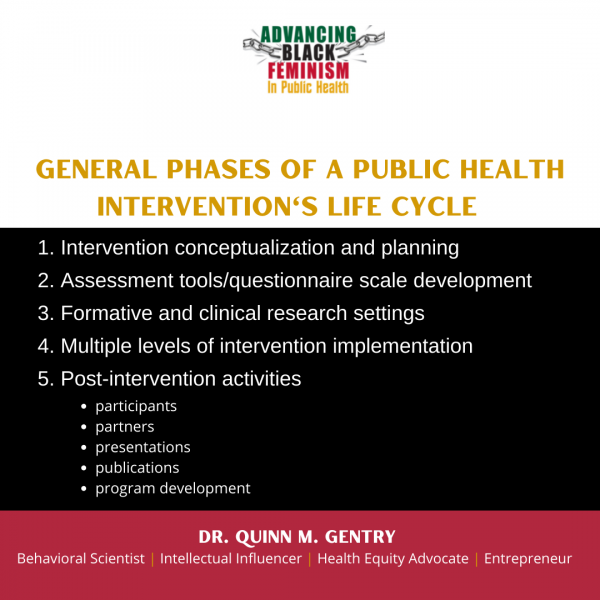

This blog provides guidance for multiple level interventions for advancing black feminism in public health. While I focused on addressing one aspect, it is imperative that public health practitioners value black women’s unique experiences in all phases of a public health intervention life cycle.

More by Dr. Quinn M. Gentry here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.