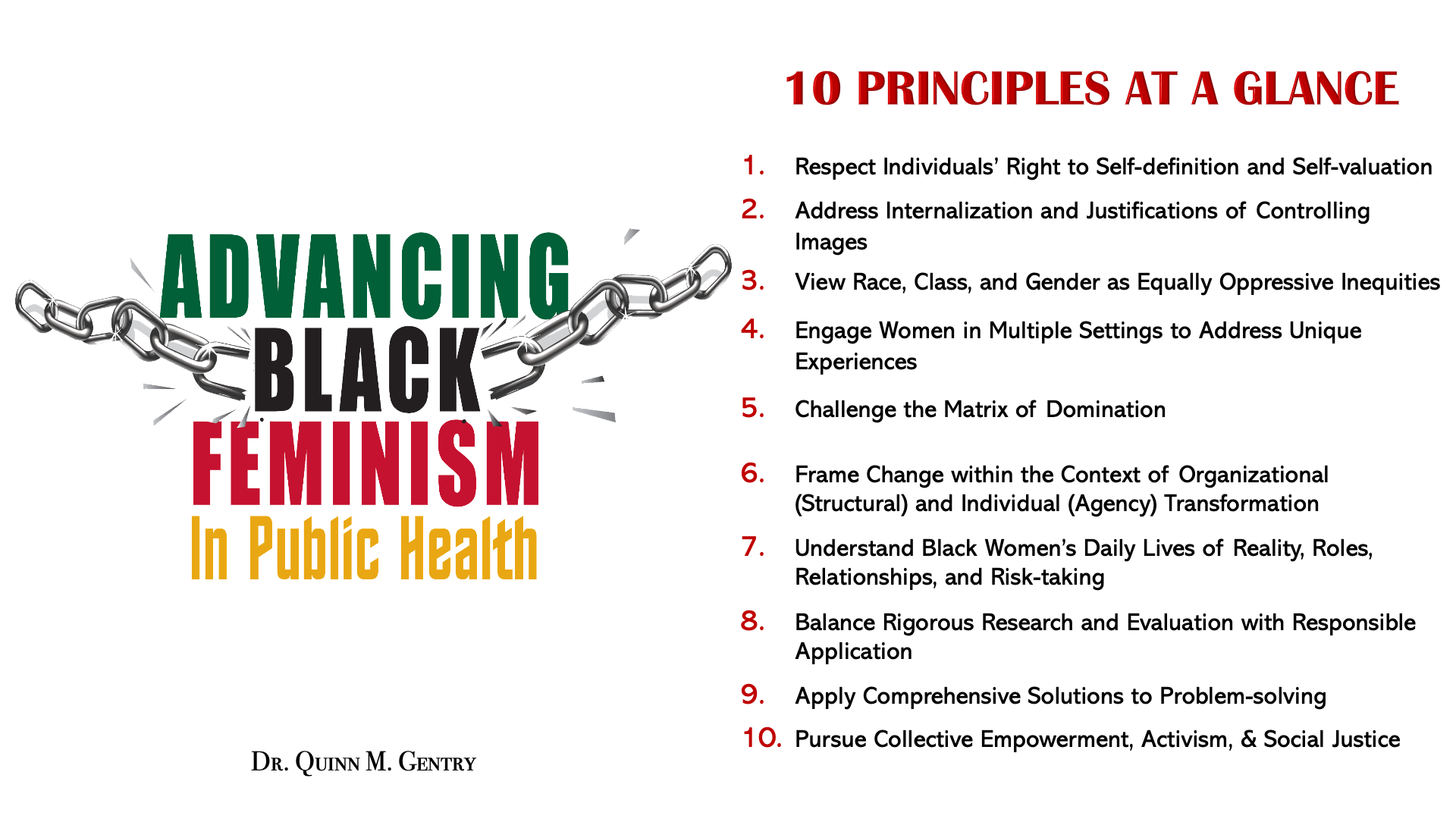

Welcome to my blog on “Advancing Black Feminism in Public Health.” My goal is to move black feminism from the margins to the center of public health by applying 10 key principles as legitimate and comprehensive frameworks for adequately addressing health threats and related social and structural determinants of health in the lives of black women and girls.

Dr. Quinn M. Gentry

In this blog, I highlight the significance of principle no. 1: Respect Individuals’ Right to Self-Definition/Self Valuation in advancing black feminism in public health. Definitively, self-definition/self-valuation is the power to name one’s own reality and identity. When applied in public health it permits black women to engage diverse representatives of the public health and medical systems with dignity and the courage to speak up for oneself. As public health embraces the spirit of health equity, the principle of self-definition/self-valuation allows for the potential for black women to emerge as experts of our health-related experiences, thereby leading to co-created health solutions.

The principle of self-definition/self-valuation became real for me in 2000, on the front lines of public health. I was working alongside Principal Investigator Dr. Claire Sterk (Emory University President Emeritus) on a multi-year National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) study when she gifted me a copy of Hill Collins’ Black Feminist Thought in preparation for my dissertation. I will never forget “Teresa”, a study participant in this NIDA-funded Health Intervention Project (HIP). In fact, I credit Teresa for my paradigm shift in bridging the gap between black feminism and public health. She insisted that I see her unique experiences as a woman at risk for HIV. After a few tense exchanges primarily around her disdain of my characterizing the neighborhood she grew up in as a ‘poor’ and ‘drug-infested’ community, I realized that “Teresa” was embodying Audre Lorde’s, self-health warrior quote:

"If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”

Audre Lorde, Black Feminist Tweet

Just as Lorde demanded that oncologists put more thought into creating an intervention uniquely designed for her, so too was “Teresa” fighting to be seen as a unique individual whose full life experiences, goals, dreams, hopes, strengths, and vulnerabilities must be considered when building an effective intervention.

Self-definition/self-valuation in public health helps us to understand how black women are objectified, as we are forced to fit our intersectional health threats into pre-determined intervention boxes. “Teresa” was a high-earning sex worker who leveraged her father’s entrepreneur status, as well as her own “Pretty Woman” persona — her beauty, body, and charm — to attract married, affluent men who work in the city and reside in the suburbs, similar to “Vivian” (Julia Roberts) in the movie Pretty Woman. This observation raised my consciousness about the HIV risks among middle-class black women residing in the suburbs. Later blogs explain my attempts to raise the consciousness about suburban black women’s risk factors for HIV. Imagine the uproar I caused in suggesting that suburban black women share the same men with “Teresa”!

Self-definition/self-valuation in public health is complementary to several existing theories and frameworks that should be moved from the margins to the center of problem-solving for black women and girls. In brief, these include:

I argue that the dismal health outcomes for black women of all classes is grounded in repeat patterns of blatant disrespect of self-definition/self-valuation in behavioral and medical interventions. Not only is this evident in HIV, it is even more pronounced in child and maternal health and cancer treatments.

Women’s studies scholars can be great collaborative partners for operationalizing self-definition/self-valuation via incorporating practices that address intersectionality, as originally conceptualized by Dr. Kimberle W. Crenshaw, into service delivery models to meet the multiple health needs among black women.

Self-definition/self-valuation can inform innovative approaches in public health by enhancing black women’s roles as “co-creators” in planning and evaluating evidence-based interventions.

Create safe spaces within scientific studies for black women to self-define/self-value as legitimate aspects of public health research and interventions. “Teresa” rejected being narrowly defined simply as a drug-addicted, HIV-positive, sex-worker. She insisted I see her as a prominent businessman’s daughter, the mother of five children adored by their grandmother, and a woman who completed two-years of college and runs a profitable business. Thank you “Teresa” for humanizing my research experience, as you forced me to respect your unique experiences — not as an outlier within traditional research, but as an opportunity to practice the principle of self-definition/self-valuation as core to implementation science. This opportunity is optimized when we advance black feminism in public health by putting our collective intellectual capacity to work for a change.

More from Dr. Quinn M. Gentry here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.