This post draws heavily from review papers by Ebi et al. (2021), Xu et al. (2020), and Jaffe et al. (2020). Due to the broad agreement between these papers, my in-text citations are only for the more unusual points.

***

Smoke from California wildfires, pushing east.

— CIRA (@CIRA_CSU) August 6, 2021

This morning's view from above. pic.twitter.com/hhxAvgEjkq

The last handful of years have seen megafires raging across North America, Australia, and Brazil. Smoke from these fires can result in terrible air pollution in places that are mostly clear. For example, in early August, Denver, Colorado (the capital of my home state) had the highest air pollution of any city in the world due to fires in California.

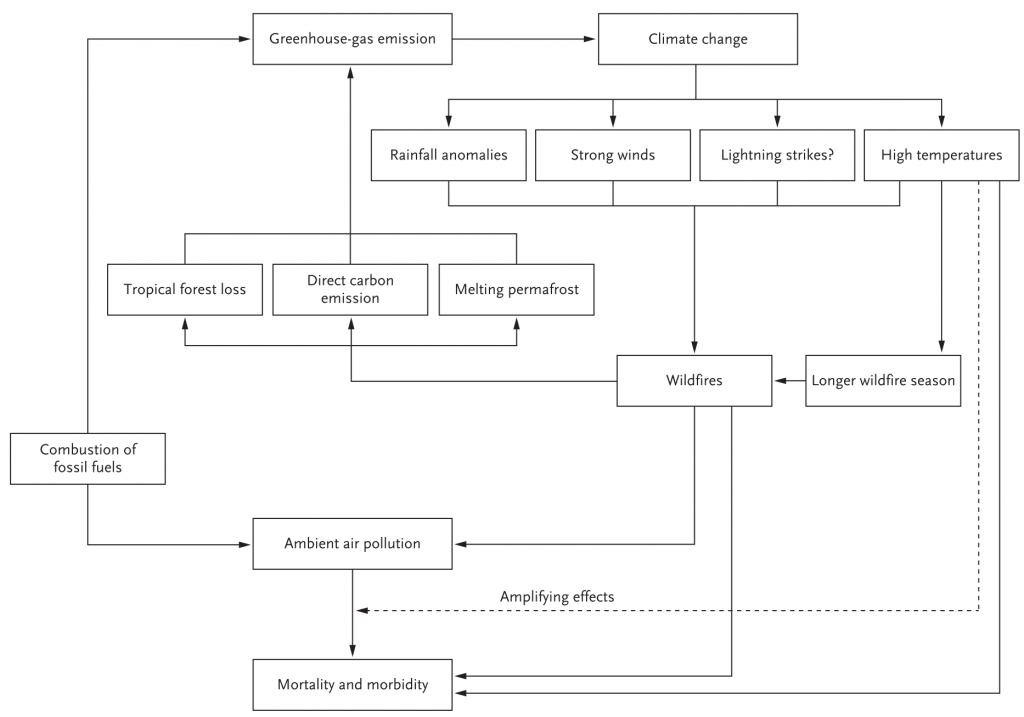

In 2012, the global mortality burden from wildfire smoke was estimated to be between 260,000 and 600,000; however, given the increases in both population and extreme wildfires in the years since then, these numbers have likely grown substantially. In addition to historical wildfire suppression (resulting in overly-dense forests), climate change has been implicated as a major contributor to increases in wildfire season length and acres burned. Thus, the burden of wildfires is projected to continue increasing, and this may result in a positive feedback loop, as wildfires themselves release greenhouse gases (80–90% of the emissions by mass from biomass fires are CO2). The figure below illustrates the interconnectedness of these processes, as well as how air pollution from wildfires impacts our health.

Xu et al., 2020, Figure 1: Potential reinforcing feedback loop of climate change, wildfires, and health risks. Note: the dashed line indicates that high temperatures could amplify, or enhance, the effects of ambient air pollution on mortality and morbidity.

Of course, there are other health concerns due to wildfires not directly related to air quality, including contamination of drinking water with toxic ash, exposure to flames, and intense stress, but this blog will focus on the air pollution aspect.

In contrast to other kinds of air pollution (e.g. air pollution usually found in urban areas as a result of automobile exhaust or industrial processes), wildfire smoke concentrations are significantly higher and the pollution contains different compounds. Especially as human populations continue spreading out (expanding the “wildland-urban interface”), more wildfires end up burning human structures and cars. In addition to being more expensive and traumatic for residents of areas affected, this burning releases more toxic emissions. Some of the compounds in wildfire smoke tend to stay localized, of concern primarily for firefighters, but other compounds can be transported much farther, of concern for the population at large.

The strongest evidence we have for wildfire smoke affecting health is from studying adverse respiratory health events, such as hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and respiratory infections. Specifically for asthma-related events, researchers have found that wildfire particulate matter increases the health risk more than urban particulate matter. In addition to containing potentially more toxic compounds, wildfire particulate matter also tends to be of smaller size (so the particles can more deeply penetrate systems of the body) and occur contemporaneously with increased ozone and temperature, which may amplify the health risks. There is also some evidence of increased risk of cardiovascular health events such as out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

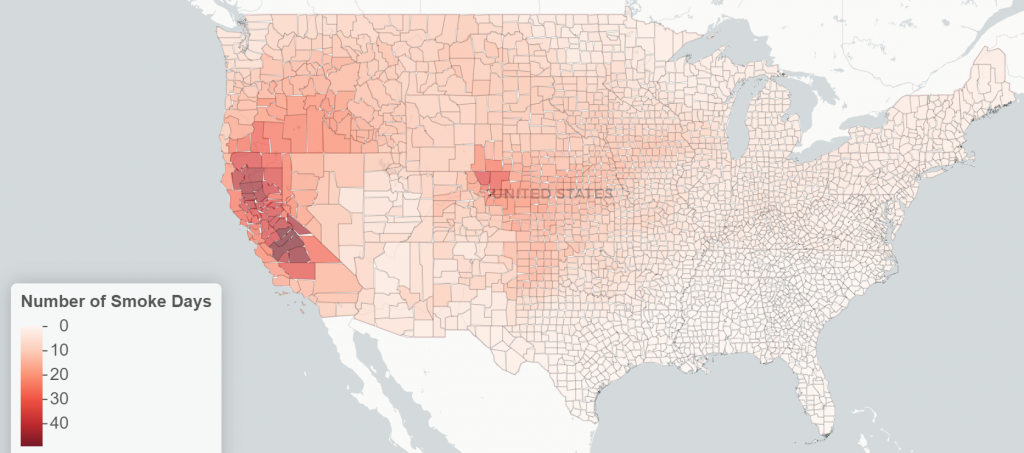

Other health risks associated with wildfire smoke include low birth weights for babies in gestation during a wildfire, eye irritation and corneal abrasions from smoke particles, and increased rates of infectious diseases, such as influenza and COVID-19. A paper published in August found strong evidence that smoke from wildfires in 2020 led to more cases and deaths from COVID-19. For context, here is a map of the number of heavy smoke days over the US in 2020, obtained from this interactive visualization.

Identifying demographics who are especially vulnerable to wildfire air pollution is critical to informing public health strategies. Groups that are highly exposed to intense smoke events include outdoor workers and the homeless, as well as residents of homes that are not well sealed to ambient air. People with increased health risks during smoke events include those with pre-existing respiratory or cardiac conditions, older adults, and individuals with low socioeconomic status; however, the latter requires more study (in contrast to urban air pollution, there have been few epidemiological investigations of differential risk from wildfire air pollution).

Other prominent gaps in scientific evidence are the long-term health impacts of exposure to wildfire smoke and the health impacts of prescribed fires. Long-term health concerns relate to the effects of repeated exposures across fires or fire seasons as well as to the unique characteristics of wildfire smoke, on health aspects such as childhood development and progression of chronic disease.

Prescribed burning is used to maintain ecosystems that depend on fire and to prevent larger wildfires, a natural consequence of fuel buildup, from wreaking havoc. Prescribed fires typically generate less smoke than wildfires, but as of the writing of this blog, there have been no epidemiological studies quantifying the health impacts of prescribed fire-specific air pollution. This kind of research is needed to evaluate the health and economic benefits of prescribed burning. One factor complicating land management decisions is that prescribed burning often occurs in more rural areas, where air quality monitoring and management is more limited; in some regions, this poses an environmental justice problem.

To protect ourselves from wildfire smoke, actions can be taken both prior to and during wildfire events, at both the societal and individual levels.

At the societal level, in addition to forest management practices (such as prescribed burning) to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires, hospitals and other community facilities can prepare for wildfire season (e.g. by acquiring / maintaining air filters), officials can emphasize the health risks of smoke across multiple channels of communication (focusing on vulnerable sub-populations), and, with a longer-term view, public and private sector entities can invest in decarbonization to mitigate climate change (advocated in my seventh blog).

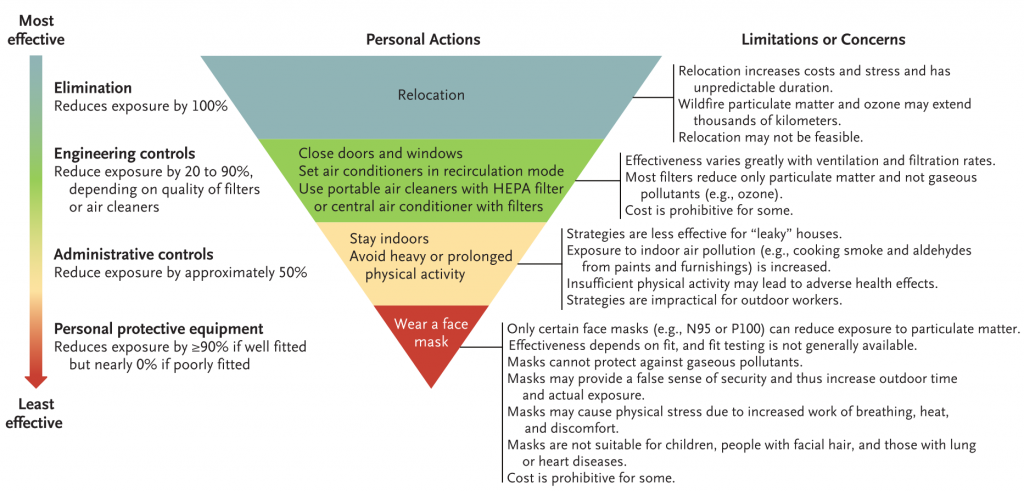

The figure below describes actions that can be taken at the individual level and highlights some of the limitations of these approaches.

Xu et al., Figure 2: Main actions that individual people can take to reduce exposure to wildfire smoke and its health risks. Note: The use of N95 or P100 face masks certified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) or their potential equivalents (e.g. KN95 or P95 masks) is recommended. Recommendations regarding the use of face masks, air conditioning, and air cleaners can be found here.

Other recommendations include driving carefully when smoke reduces visibility and keeping children away from ash (which may contain toxic chemicals). For more information on real-time air quality and protective measures, check out the resources in the following section.

***

Recommended reading / listening / exploring:

More on Ellen Considine here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.