Migrant workers in low-to-middle income countries, including the Philippines, are considered significant contributors to host countries’ gross domestic product and other economic indicators.

However, these workers are also known to have limited access to mental health services in their adopted homes. Worse, they are at heightened risk of experiencing mental health problems in unfamiliar environments, where their legal and health care options may be significantly limited.

Studies on migrant workers have demonstrated their vulnerability and that adverse mental health outcomes are linked with combinations of stress, marginalization, discrimination, and/or abuse. For example, overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) in China were reported to have experienced mental health conditions due to relationship issues with their family in their home country, while facing cultural barriers in their host country. Such conditions can also lead to the inability to perform their duties within their respective workplaces, and thus, can compromise their livelihoods.

At the height of COVID-19, mental health problems concerning migrant workers became and continue to be even more apparent. However, seeking professional help and other interventions related to mental health remains out of reach of many, with some deterred by fear of contract termination, discrimination from their community, or, at worst, repatriation.

This situation reflects the existing stigma surrounding help-seeking behavior, on top of other prevailing systematic problems (e.g., lack of available psychological assistance and services, lack of awareness of available services for migrant workers, etc.).

Most of the time, migrant workers feel alienated while navigating their host country’s health system — and this is all the more so true when it comes to seeking care for their mental health. While it is crucial to foster a safer — decent, supportive, and humane — environment, much of the necessary system-level changes and improvements require policy reform. To rethink migrant workers’ mental health means shifting the paradigm from a medicine-centric view on mental health to a broader systems-level approach.

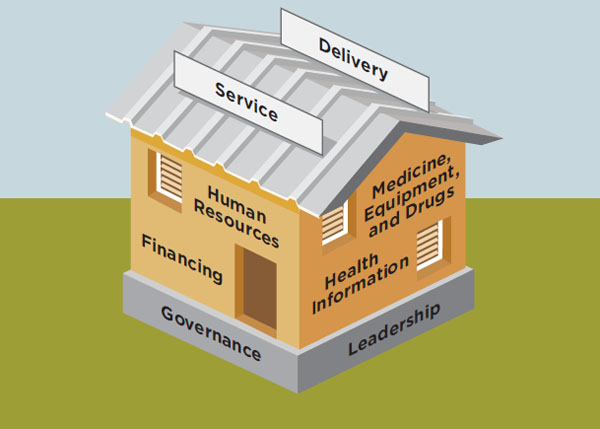

The policy analysis of Silva et al. (2020) highlighted the need to introduce specific interventions for OFWs, based on the identified policy gaps across the entire process of worker migration. Such solutions can be clustered based on the World Health Organization’s health system building blocks. Some of the recommendations include, but are not limited to:

It is high time to rethink how our governments prioritize the mental health of migrant workers. As vital contributors to nations’ economies, migrant workers only deserve to be treated co-equal with other citizens and to be given the same entitlement to a full range of health care and mental healthcare benefits.

While COVID-19 may have hampered numerous health programs, the best measure of an effective and resilient health system is how inclusive it is for vulnerable and marginalized populations, such as migrant workers in this modern-day diaspora.

As the pandemic rages on and we hopefully move into a new phase of rebuilding and recovery, there is no doubt that migrant workers will be even more essential. Let us hope the lasting memory of the contribution of migrant workers drives our societies and political systems to properly value and reward their contribution

Claire Kumar, ODI Tweet

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.