The menopause is a natural part of the female life cycle. But why do women become invisible after the menopause? Dr Jen Gunter answers my question 'Ain't I A Woman?"

Today, we will explore work and gender pay gaps through the lens of negotiation and reproductive wellbeing.

The conditions in which girls are born, grow up, live and work determine their health outcomes later in life. Work is good for our mental and physical well-being. But positive benefits of work are dependent on the nature, quality, and social context of working. We are all living longer and working for many more years than ever before. In 2019, women made up 39% of the global workforce; today women live up to 5 years longer than men, delay the onset of their first pregnancy, and will have 2 babies on average.

So women are having fewer children, living and working for longer, but are paid less than men.

There is no objective evidence that women are any less capable than men in the workplace, yet women are paid less than men for doing the same amount and type of work. The gap gets wider when you look at the effect of intersecting identities such as race, ethnicity, and ability.

Conditions that prevent women from entering and staying in the labor force — such as differential access to health, education, security, and political power — drive and maintain the gender pay gap.

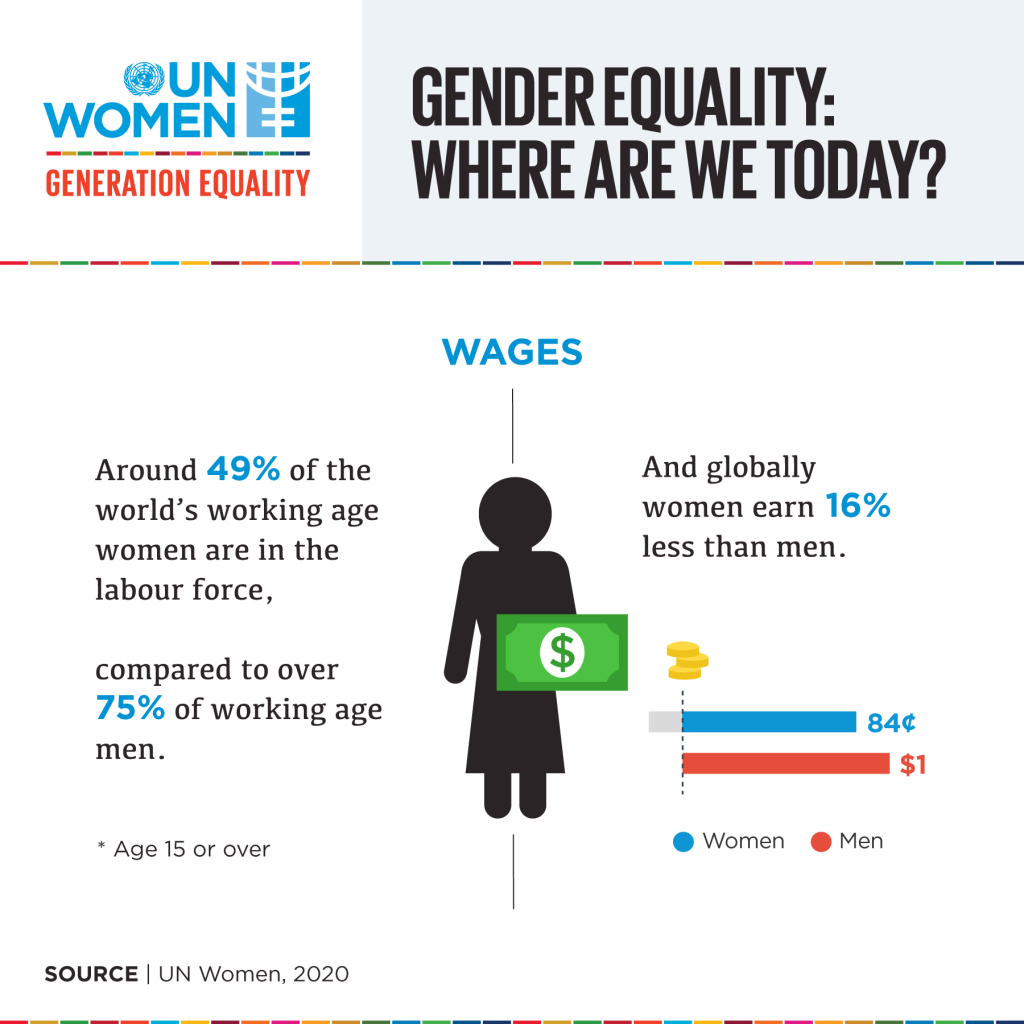

Due to underrepresentation in the paid labor market globally, only 49% of women of working age (15-64) are in the labor force, versus 75% of men in the same age group. Women spend twice as much time as men in unpaid work and bear the disproportionate burden of caretaking and household responsibilities. This is likely to be worsened following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite these depressing statistics, many of us believe in gender equity. When asked, 70% of women and 66% of men in 142 countries agreed that women should work in a paid job. 80% agreed that women should be paid equal to men for doing the same job.

Balancing work and family responsibilities was highlighted as the most significant barrier for women at work and gender equity.

Periods and pregnancy do not stop for pandemics. Reduced funding, service closures, and disruptions in the supply chains have affected women’s access to safe and timely sexually and reproductive health services such as contraception and abortion services.

The number of unintended pregnancies has increased in lower and middle-income countries, particularly amongst teenage girls.

(Caption for the left):

Society simultaneously values and punishes women for their ability to procreate. Women pay additional taxes for possessing ovaries in the form of the ‘pink tax’, unfavourable parental leave policies, out of pocket expenditure for accessing sexual and reproductive health services, etc.

The pink tax describes the illogical phenomenon whereby products such as tissues and razors with similar production costs are marketed to women at a higher price than to men.

Despite being one of the richest countries in the world, the USA is one of the few countries that does not mandate and enforce paid parental leave across all occupations. Financial protection and job support for all pregnant people and families, regardless of their pregnancy outcome, could be a game-changer in levelling the playing field.

Not all pregnancies end with a live baby. It is unfair that women who experience a miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or stillbirth are forced to return to work without financial support and a baby to show for it.

At work, you may be faced with negotiating a pay raise, promotion, or parental leave. Women are commonly wrongly stereotyped as being worse negotiators than men because they are not “assertive” or “tough enough”. Such stereotypes are propagated by research which frames abilities without analysing the environments which promote or hinder different negotiation outcomes.

We must recognise that majority of the research around gender and negotiation focuses on the experience of cis gendered heterosexual men and women. The literature and narrative are also predominantly informed from Westernised ‘individualistic’ cultures (e.g. USA, UK), which promote self-interest and competition. In contrast, in ‘collectivist cultures’ (e.g. Venezuela, South Korea), where concern for the group is prized, women are regarded as much fiercer negotiators. Gender alone is an unreliable predictor of negotiation outcome and behaviour. However, ‘gendered’ contexts, heightened ambiguity, and organisational culture have been shown to have the greatest impact on negotiation outcomes for women.

Asking for a pay raise is perceived as ‘masculine’ because money is status-linked and associated with occupying positions of authority, which are commonly male dominated. Women may be hesitant to negotiate a higher pay raise because of fear of social resistance and being labelled as bossy or aggressive. On the other hand, parental leave negotiations are perceived as ‘feminine’. Men may want to negotiate more flexible and family-friendly work arrangements, but they fear more backlash than women for doing that.

When men and women are given the same amount of information, they perform equally well in negotiations. Therefore, workplace policies which promote sharing of clear instructions about the promotional and hiring processes, pay structures, and behavioural norms of workplaces level the playing field.

Organizational culture influences the power dynamics at work. Diverse and inclusive environments are more likely to have balanced representations of multiple identities. Conversely, in homogenous work environments, certain identities may be associated with higher status and leverage. For example, in Engineering and Tech companies, which are male dominant, men report a higher psychological experience of power. This means they are more prone to negotiate, because they expect better terms and feel entitled to more.

Your identity can influence your information search whilst preparing for negotiations. In environments where men earn more than women, women enquiring within convenience networks made up of predominantly other women may obtain skewed information, which encourages them to aim lower when negotiating pay and promotion packages.

Creating diverse and truly inclusive work environments mitigates the effect of power dynamics being skewed in the direction of identities and social capital.

To move the dial on equalising pay, we need to de-bias systems, not people

Iris Bohnet, co-director of the Women and Public Policy Program at Harvard Kennedy School Tweet

In my pieces, I use the terms:

Girls, women, womxn, pregnant people, and birthing people to refer to some of the reproductive health experiences of individuals assigned female at birth. Not all women have cervixes, not all people who have cervixes identity as women.

Minoritised in place of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous & people of color), POC (people of color), BAME (Black, Asian & Minority Ethnic), and BME (Black & Minority Ethnic) to recognize that individuals and communities do not naturally exist as minorities; but instead have been assigned this identity in response to dominant socio-economic and political narratives. ‘Minoritised’ intentionally highlights contemporary power imbalances rooted in historical events of slavery, colonisation, and other systems of oppression.

What good is a right if it doesn’t guarantee you your freedom? Find out more in, “Reproductive Justice: Why We Police Women’s Uteruses”

The menopause is a natural part of the female life cycle. But why do women become invisible after the menopause? Dr Jen Gunter answers my question 'Ain't I A Woman?"

The menopause is a natural part of the female life cycle. But why do women become invisible after the menopause? Dr Naghat ARif answers my question " Ain't I A Woman?"

In this game of gonads, who decided that a testicle is worth more than an ovary?

To deputise a complete stranger to interfere with a woman’s health choice is constitutionally, medically, morally and ethically wrong. That's the end of my sentence.

Cervical cancer can be prevented. When detected early it can be treated and cured with surgery. As we mark the one year anniversary of the "Cervical Cancer Elimination Day of Action", I reflect on the role of surgical systems in eliminating cervical cancer.

Adolescents make up 16% of the population and straddle the sometimes uncomfortable gap between childhood and adulthood. Seeking out information on the internet makes sense but at what cost?

Periods don't have to cost us education, equity and the environment

We had no say in the decision of when, how, where and to whom we were born. Yet this was one of the most important decisions in our lives, which continues to impact us today.

More from Isioma Dianne Okolo here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.