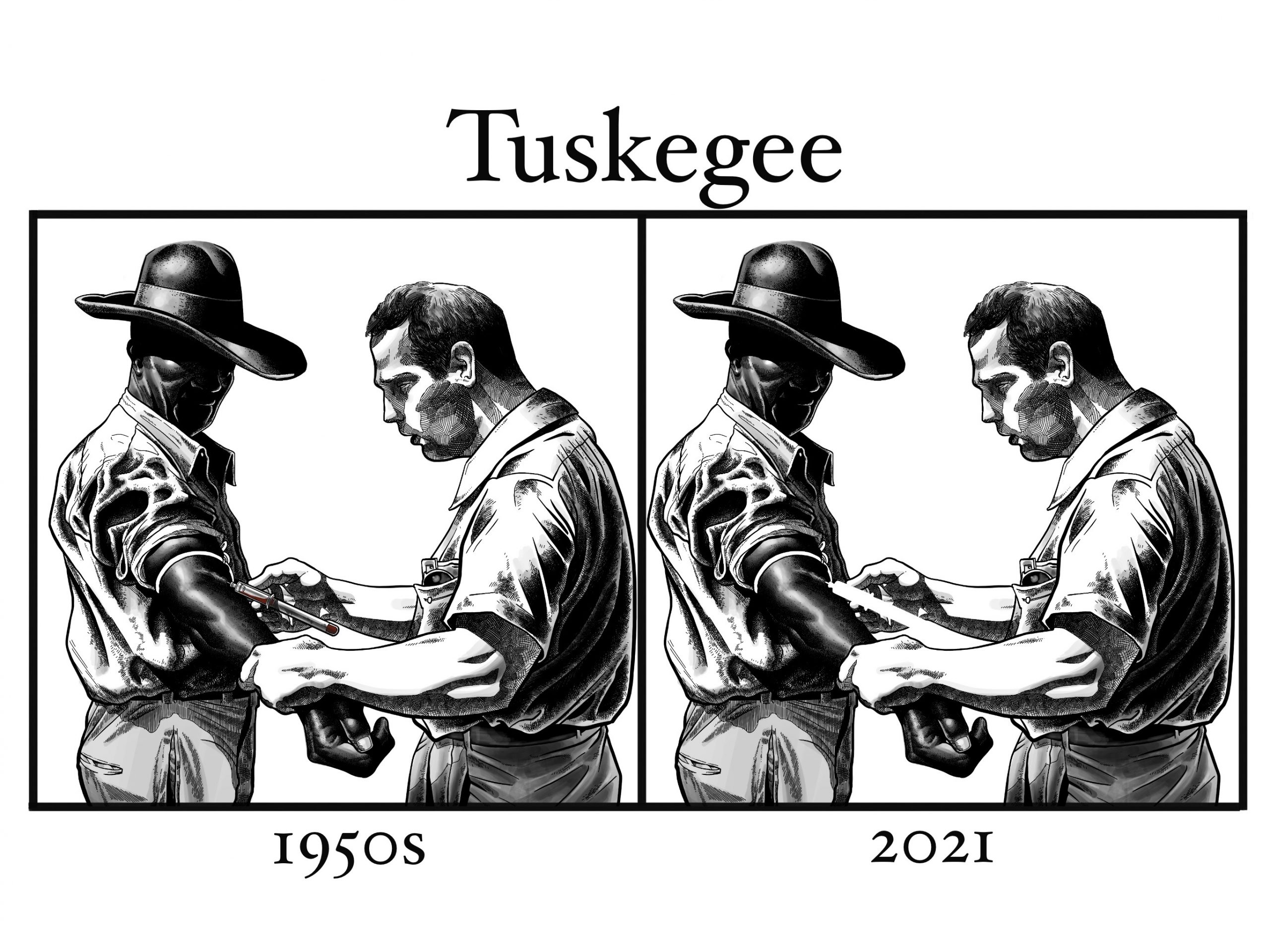

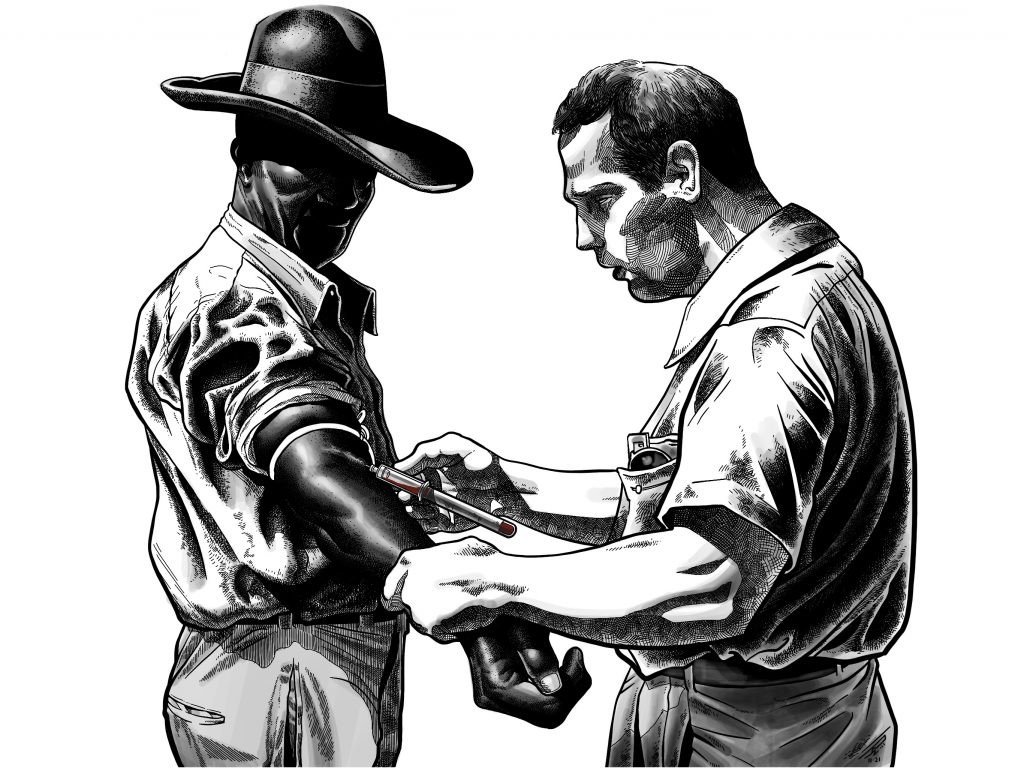

The illustration above is a study of a photograph from the National Archives of Atlanta. My former art teacher, the late great David Omar White, once taught me that the only way to spend enough time looking at a great photograph is to draw it. This illustration is my testament to spending time with this compelling, devastating picture. It is my chance to delve into its imagery, from the way the cast shadow anonymizes the person’s face on the left, to how tightly his wrist seems to be gripped by the person on the right. It is my way to think about the context of one of the darkest chapters in American Medical history, and look forward to when the name of a city will no longer be a one-word answer.

More from Dr. Ryan Montoya here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.