Armed conflict is a global health threat and has severe consequences on the health of affected populations. Health workers are key to an effective public health response, and their role becomes more critical in conflict settings.1 Despite their heroic work, their mental health and well-being is often overlooked.

This blog post is based on a conversation with Diana Rayes, MHS, an International Health PhD student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Q: What is the current political situation in Syria?

A: The political situation in Syria continues to be extremely dynamic and complex with a multitude of armed actors on the ground and shifting geographies. The conflict in Syria, which began after the Syrian government cracked down on popular uprisings in 2011, has resulted thus far in reported estimates of over 600,000 people dead or missing2, 6.6 million Syrian refugees worldwide, and 6.7 million internally displaced Syrians.3

Q: What is the structure of the healthcare system in Syria today?

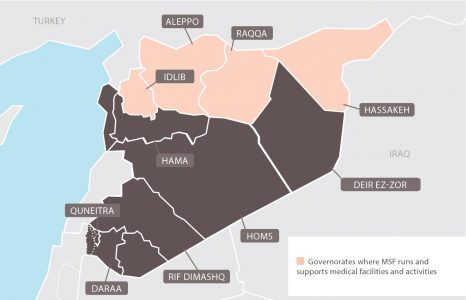

A: The healthcare system in Syria is fragmented, with roughly three separate systems operating today. There is one system in the northwest, one in the northeast, and a third in the rest of Syria controlled by the Syrian regime (See Figure 1 for a visualization). Coordination between these three systems is limited, and they rely almost entirely on humanitarian aid for their operations.

Q: How do you describe the mental health situation in Syria?

A: The mental health situation in Syria has always been challenging, even before the onset of the war. There are very few psychiatrists in the country, and mental health policy is practically non-existent.

Due to a lack of population-level data, it is difficult to identify the most common mental health conditions. However, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder have been reported among Syrians, both inside the country and among those who are displaced.

Part of the work that I do is to explore other culturally specific mental health conditions that are not based on these Western criteria. These include severe trauma and unexplainable forms of grief that are difficult to cope with. Examples include active and recurring trauma and feelings of hopelessness among people who have lost their entire families and homes.

Q: What are the main mental health issues facing health workers in Syria?

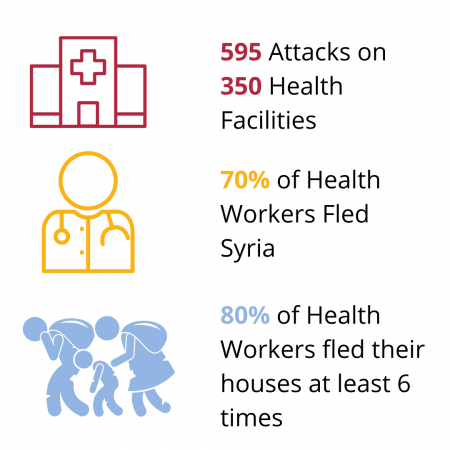

A: The regular and severe attacks on healthcare facilities in Syria cause health workers to live in constant stress, trauma, fear, and grief when losing colleagues or loved ones. The fleeing of thousands of health workers out of Syria has created an extra burden on the remaining health workers in the country. They often feel helpless and under-qualified, and some work up to 80 hours per week6.

Many days we can’t speak to our families when we get home, because of what we see [at work] … we can’t look at our children. We think, ‘What if this happens to them? ... We’re doctors but we’re also human.

Abulaman, a doctor working in Northern Syria during a WHO survey (7) Tweet

Q: Has there been any intervention to support health workers’ mental health in Syria?

A: As part of a study we did, we asked doctors if they are accessing mental health or psychosocial support through their respective organisations8. We found that there is limited specialised support being provided to them. This is mainly due to the lack of available specialists and lack of understanding of how these health workers can be supported.

Examples of coping mechanisms used by health workers include feeling grateful that they have families to spend time with after long and stressful workdays. Their spiritual beliefs also help them to keep going, whereby they rely on beliefs around fate and feelings of fulfillment that they are risking their lives to help others. Nonetheless, these are not long-term solutions and health workers require specialized mental health care.

Q: What are your recommendations for research, interventions, and policy?

A: Research priorities include large scale quantitative surveys to assess the mental health needs of health workers in Syria.

There is a critical need to increase specialised mental health and psychiatry trainings in Syria. Interventions such as trainings on self-help and peer support among health workers can be piloted in Syria. Such interventions must be needs-based and should involve health workers in the design and implementation processes.

On a policy level, strengthened coordination between the different healthcare systems is required. This includes increasing efforts through humanitarian policy and the critical role of NGOs and UN agencies in addressing mental health issues. It is also essential to address the underlying political determinants of mental health issues. Mental health of Syrians, including that of health workers, will continue to deteriorate if the war persists.

Diana Rayes is a Syrian-American PhD candidate at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health where she is researching the impact of conflict and displacement on refugee and migrant health. Diana is currently the qualitative research lead for the R2HC-funded project at the University of California, Berkeley on the impacts of attacks on healthcare in Syria. Diana was formerly a Non-Resident Fellow with the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, focusing on public health trends and refugee issues in the MENA region and has previous affiliations with the World Health Organization, the Syrian American Medical Society, and the Lancet Commission on Syria in her work on the humanitarian response in Syria.

More from Rasha Kaloti here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.