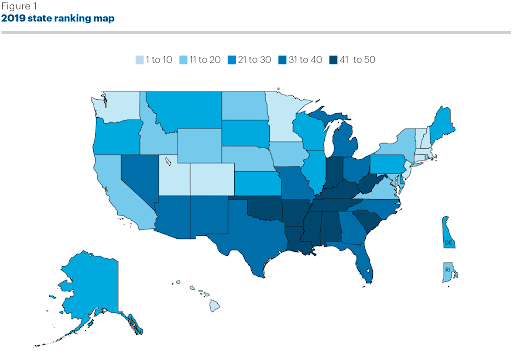

I call Arkansas my home; public health experts know it as the state ranked 48th in the nation for health outcomes. Louisiana, the state where I was born and where my grandma and her infamous gumbo reside, follows in 49th place. Mississippi, home to many of my friends and mentors, lands in 50th place.

These abysmal rankings are decided by an algorithm blending collective metrics of health behaviors, environmental factors, policy, clinical care, and, perhaps most important, the health outcomes of the citizens who live there.

Maps like Figure 2, taken from the 2019 Annual Health Ranking Report feel foreign to me: on the one hand, they highlight many of the struggles and challenges communities like my own often face. On the other, they cement the South as the objectively worst region for health in America, hiding the diverse and varied cultures, traditions, and individuals that call the region home. When I look at this data, I don’t see the nuanced and vibrant people I call my neighbors.

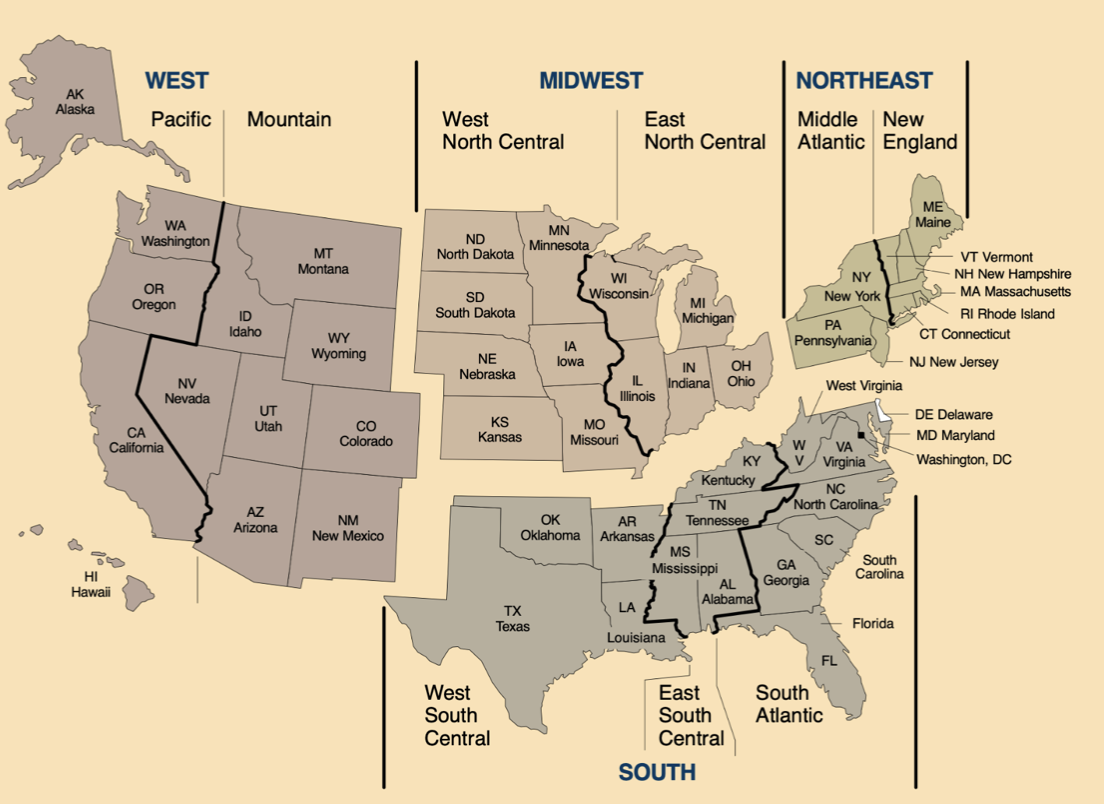

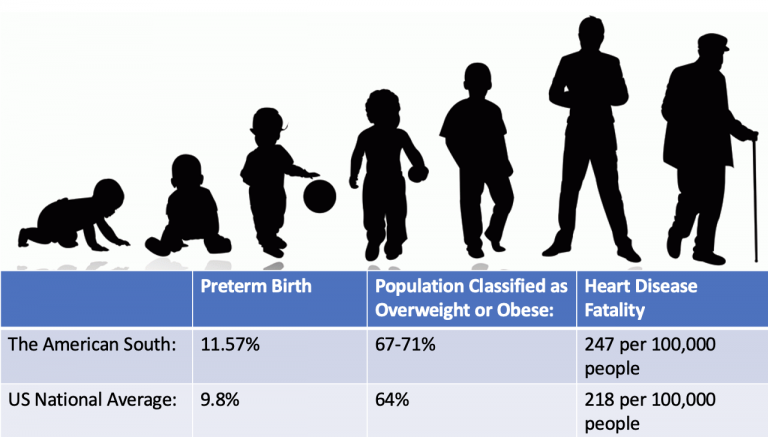

The American South, comprising the 17 states shown in Figure 3, has a notorious history of some of the worst health outcomes, year after year. The inequities begin before birth: preterm birth rates are as high as 14% in Mississippi and as high as 20% in some of Mississippi’s most under-resourced counties. They persist throughout a lifetime: being overweight or obese affects nearly 67-71% of the population in Southern states, and many Southern states possess the nation’s highest diabetes rates of up to 14%. And they continue to add up: often, these morbidities lead to a disproportionate rate of premature death due to cardiovascular disease and other chronic illnesses. These inequities are compounded by racial disparities, with Black Americans experiencing nearly all of these illnesses at a much higher rate due to a long history of racial inequity and pervasive injustice.

While these maps and statistics may make these inequities seem like a problems of the South, these glaring disparities serve as a microcosm of the larger inequalities facing America. Statistics and data also rarely tell the full story.

My favorite poem is Wislawa Szymborska’s A Word on Statistics. Studying linear regression, sampling, and survey methods in college, I have learned there are little limitations as to what statistics can measure. Rather, the more pressing question is what statistics should measure. What I love about Szymborska’s poem is its indictment of statistics when improperly applied. Statistics inform policymakers and the public of the most pressing problems, but they are ill-equipped to determine the worth of an individual or offer solutions to a community in need. Statistics also tend to be relayed flippantly; infographics are often flashed during lectures, as quips during a newscast, or as striking facts in a CNN alert on your phone. Rarely are they reported in their full context, with due consideration of all the causes, people, and consequences behind the scathing statistics. Statistics prey on the pernicious human tendency to organize and categorize. They show only the inferior health outcomes, missing, and even obscuring, the leaders, changemakers, and innovators that also reside there.

I find solace in the socio-ecological model of public health: a holistic approach that acknowledges the multitude of factors that contribute to health at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. To better inform interventions and preventative practices, the socio-ecological model requires an understanding of an individual’s positionality and health behaviors, the complex personal relationships that influence an individual, the communities in which individuals reside, and the broader societal factors underlying health, such as local economic and educational policies that contribute to inequality .

Public health encompasses more than statistics and symptoms; it is the stories and lived experiences of individuals, families, and communities.

Claire Bunn Tweet

To deepen my own understanding of public health, I will interview experts, including rural sociologists, community health workers, private sector healthcare workers, policymakers, and researchers. I hope to explore the stories beyond statistics and behind unique healthcare interventions within the American South. Innovation in the South could offer creative solutions to other regions in America and, eventually, other historically marginalized communities around the world.

Public health encompasses more than statistics and symptoms; it is the stories and lived experiences of individuals, families, and communities. Through this blog, I seek to explore and uncover those stories and the environmental and societal structures that shape health outcomes in Southern communities. There are many narratives of the American South, and I hope to provide an insider’s view of my journey to better understand my own and the forces that have shaped the communities that raised me.

2019 annual report | Ahr – America’s health rankings | Ahr. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2019-annual-report. Accessed September 10, 2021.

Basic Statistics: About Incidence, Prevalence, Morbidity, and Mortality – Statistics Teaching Tools – New York State Department of Health. (n.d.). Department of Health. Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/chronic/basicstat.htm.

Bureau USC. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed September 20, 2021.

Chapter 1: Models and frameworks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_models.html. Published June 25, 2015. Accessed September 10, 2021.

Stats of the states – preterm births. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/preterm_births/preterm.htm. Published February 9, 2021. Accessed September 10, 2021.

Samantha Artiga. Health and health coverage in the south: A Data Update. KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-and-health-coverage-in-the-south-a-data-update/. Published June 9, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2021.

Samantha Artiga. Advancing Opportunities, assessing challenges: Key themes from a roundtable discussion of health care and Health Equity in the South. KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/advancing-opportunities-assessing-challenges-key-themes-from-a-roundtable-discussion-of-health-care-and-health-equity-in-the-south/. Published June 19, 2014. Accessed September 10, 2021.

Szymborska W. A word on statistics. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2021/01/poem-wislawa-szymborska-word-statistics/617711/. Published January 17, 2021. Accessed September 18, 2021.

More from Claire Bunn here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.