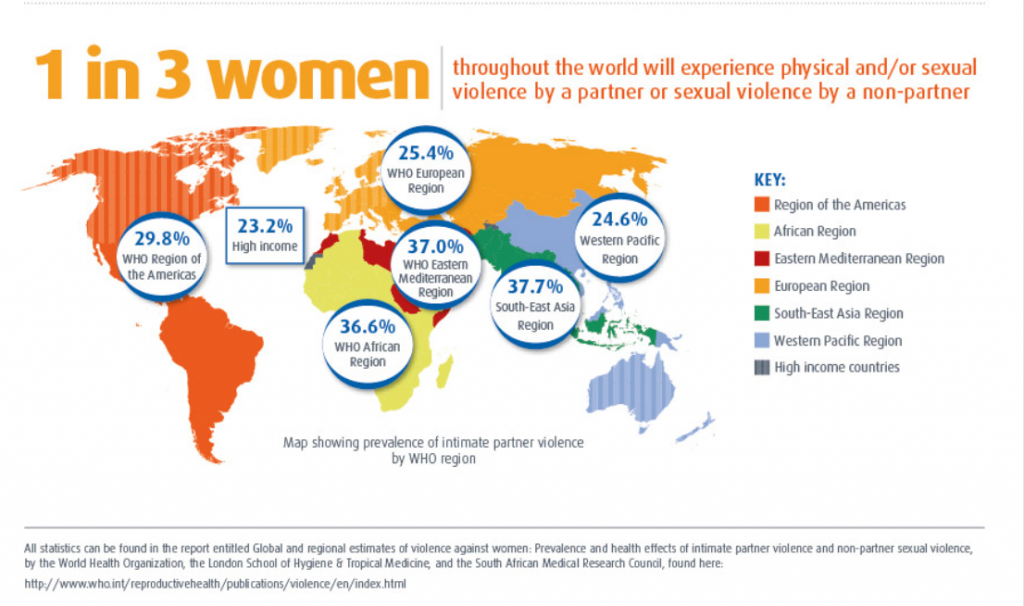

According to the World Health Organization, gender-based violence is any act of physical, sexual, or mental violence towards women that results in the suffering of women. Gender-based violence is also one of the biggest human rights violations.11 This type of violence impacts the health, autonomy, security, and dignity of women around the world. Globally, one in three women experience some form of physical and/or sexual violence in their life.7 There are several factors that increase the risk of violence such as gender inequality, violence- accepting attitudes, child maltreatment, substance abuse, and previous exposure to violence in family dynamics.11 Other factors include lack of empowerment, lack of access to health care, and societal factors that make women dependent on men.5

Cultural and social norms influence the standard of behaviors for individuals. These cultural and social norms govern what behaviors and interactions are acceptable or not acceptable. Culture and norms can increase the perpetuation of violence towards women. A cultural and societal norm that perpetuates violence is that female children are less valued in society than males, which influences social and economic environment.8

There are several consequences from gender-based violence, including physical consequences and psychological trauma. Injuries, fractures, bleeding, chronic pain, fatigue, reduced physical movements and body functions are some psychological consequences due to gender-based violence. Psychological trauma, due to gender-based violence, can involve physical inactivity, poor self-esteem, depression, anxiety, feelings of shame and guilt, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress.5

In the Southeast Asia Region, 37.7% of women face some form of physical and/or sexual violence. In the Western Pacific Region, 24.6% of women face some form of violence, which can include violence by a partner or non-partner.9 Beautification methods, such as Chinese foot binding and coiling the neck, are traditional cultural practices that can be seen as a form as gender-based violence. These practices immobilize women and hinder the women’s ability to participate within the community at the same level as men. These beautification methods are used to fit cultural norms of worth and beauty and are meant to change the body to be appealing to men.6 One such notion is the identity of the fragile female that is enforced through power dynamics, deforming and deactivating the body to elicit female subordination.6

The act of binding involved breaking all toes, except for the first one, on each foot. Afterwards, the foot is bound in cloth strips which are continually tightened. This process can begin for a girl as soon as when she is around three years old.3 A special shoe is used to decrease the foot size when the bandage is tightened. The young girl is then forced to walk on her feet to promote circulation. This process continues for two to three years and typically decreases the size of the foot to three or four inches.1

Folklore perpetuated the use of Chinese foot binding. A common folklore was an Empress in the Shang Dynasty had a clubfoot and demanded all court ladies to bind their feet as a result. Another folklore is that a prince of the Shang dynasty had a fetish with tiny feet so he made his concubine bind her feet.7 Also, it was said that the Sung dynasty ordered women to bind their feet to confine women to their homes to ensure chastity and restrict movement to prevent infidelity.1 Chinese foot bonding was tied to tourism due to European populations visiting in the late 1800’s and Europeans would buy special binding shoes for souvenirs. Also, Chinese foot binding helped prostitutes sell sexual services by marketing themselves as exotic to tourists.6 It was also believed the Chinese foot binding would tighten pelvic and vaginal muscles to give a tightness sensation during intercourse.1

There are several implications to Chinese foot binding that impact women’s overall well-being. During the process of binding, toes are lost due to the lack of circulation, and gangrene can occur due to infection.6 This deformity of the feet leaves women more prone to falls and difficulties in standing up, unable to squat, and hindered in carrying out daily activities. Women who have foot binding have lower hipbone density; fall risk then increases the likelihood of a hip fracture.3 Women also suffer from loss of stability, low femoral neck bone density, poor weight-bearing ability, and overall lack of mobility. The lack of ability to go outside can engender a deficiency in Vitamin D, which can lead to brittle bones.6 Other physical implications are pain, immobility, arthritis, and even death in some cases.7

Another traditional cultural practice — known as wearing brass neck coils — also perpetuates gender-based violence. This method is associated with the Padaung Tribe, which is originally from Burma, but now resides in Myanmar, Thailand because of political issues. There is a lack of documentation of when this practice started, but it is still done today. Folklore is that an evil spirit sent a plague of tigers to eat women. Women used these brass neck coils to protect themselves against the tigers attacking. Another folklore is that a long neck dragon became pregnant by the wind.2 The elongating of women’s necks with brass rings symbolised wealth, high status, marriageability, beauty, and the woman’s identity.2,6

Coils are one-third inch width and are constantly added during different stages of a female’s life. The process of coiling the neck begins with adding 9 hoops to the girl’s neck when she is about 5 to 9 years old. This process will continue until the girl is around 45 years old, at which point she will have accumulated about 32 coils.2 Often these women wear the same type of binding coils on their wrists and legs.6

The elongation of the neck is an illusion since it is the brass neck coils are weighted as to push down on her ribs and clavicles. Her ribs and clavicle will be weighted down to a 45-degree angle. There is constant stress on the brass neck coil wearer’s body. The brass neck coils reduce mobility in the head and neck of the women. Also, these coils limit the vertical mobility of the mandible or jaw.2 The lack of mobility also impacts the bone density of these women, which puts these women at higher risk of fractures.6 Removal of the rings is often used as punishment for adultery because of the belief that if the coils were removed the neck would not be stable and would suffocate the woman. In reality, if the rings are removed, the neck must be externally supported until the neck muscles develop appropriate intrinsic strength. In recent years, many Padaung tribe women have removed the rings when converting to Christianity. Just like the Chinese foot binding, Brass Neck Coils brings tourists to the area. These women are harassed by tourists and are leered at with a lack of sensitivity.4

These said forms of body modification are based on traditional cultural practices and social norms, but these practices have a negative impact on the women’s health in these cultures. One issue to point out is body modification methods were only done on women. These traditional cultural practices can also influence marriageability of the women, which impacts every aspect of their survival. Unfortunately, these practices make women a sideshow for tourism and source of financial profit. Some possible changes include:

1. Chan, L. M. V. (1970, April 1). Foot binding in Chinese women and its psycho-social implications. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 15(2), 229-232. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F070674377001500218

2. Chawanaputorn, D., Patanporn, V., Malikaew, P., & Reichart, P. A. (2007, May 1). Facial and dental characteristics of Padaung women (long-neck Karen) wearing brass neck coils in Mae Hong Son Province. Thailand. American Journal of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics, 131 (5), 639-645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.029

3. Cummings, S. R., Ling, X., & Stone, K. (1997, October). Consequences of foot binding among older women in Beijing, China. American Journal of Public Health, 87(10), 1677-1679. https://dx.doi.org/10.2105%2Fajph.87.10.1677

4. Mirante, E. T. (1990, March). Hostages to tourism. Cultural Survival Quarterly, 14(1), 35-38. Accessed from: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/hostages-tourism

5. Murthy, P., Upadhyay, U., & Nwadinobi, E. (2010). Violence against women and girls: A silent global pandemic. In P. Murphy & C. L. Smith (Eds.), Women’s Global Health and Human Rights (pp. 59-72). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett

6. Stone, P. K. (2012, November 13). Binding women: Ethnology, skeletal deformations, and violence against women. International Journal of Paleopathology, 2(2), 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2012.09.008

7. United Nations Population Fund (2021). Gender-based violence. http://www.unfpa.org/gender-based-violence

8. Wilson, A. M. (2012, May 11). How the methods used to eliminate foot binding in China can be employed to eradicate female genital mutilation. Journal of Gender Studies, 22(1), 17-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2012.681182

9. World Health Organization (2009). Violence Prevention the Evidence: Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/norms.pdf

10. World Health Organization (2010). Violence Against Women: Prevalence. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/VAW_Prevelance.jpeg?ua=1

11. World Health Organization (2017). Violence against women. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2024 BCPHR: An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal