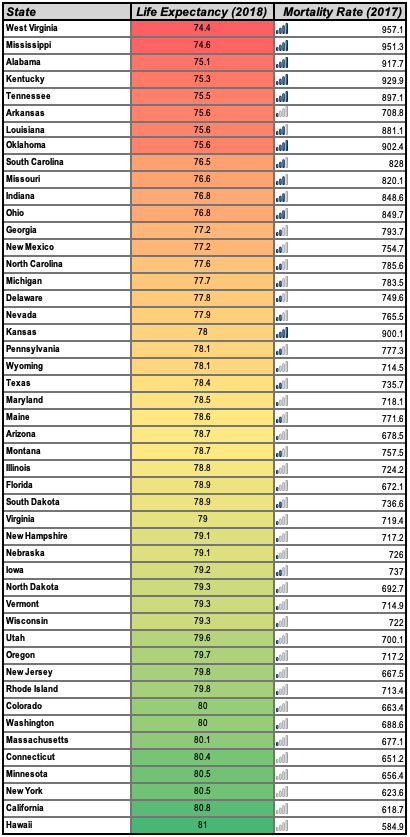

The role of public health in state outcomes is literally a matter of (longer) life or (early) deaths. For example, in 2013 the life expectancy for the average resident of Hawaii was 81 years.1 In Mississippi, the average resident could expect to live only 75 years.2 This 6-year difference in life expectancy is a health disparity that can also be seen in other forms such as mortality rates (Death rates per 100,000 people in Hawaii are below the national average at 584.93. Down in Mississippi, death rates are on the opposite end of the spectrum and above the national average at 951 deaths per 100,000 people4). In recent years (2018), at the last recording of life expectancy pre-pandemic, Hawaii remains at the top of the list for highest life expectancy at 81 years, while West Virginia moves to the bottom at 74.4 years (see table below).

This table shows life expectancy and mortality rates sourced from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. The color-coding highlights states with lower life expectancy ages in red and higher ages in green. The bar graphs accompanying mortality rate numbers give a pictorial comparison of states with more deaths per 100,000 people (more blue bars) compared with states with fewer deaths per 100,000 people.

Tempting as it may be to attribute the difference in mortality rates and life expectancy to the beaches of Hawaii or Aloha spirit, the different geographic locations (and associated regional cultures or stereotypes), or the weather, it is not that simple. Take Rhode Island and Oregon for example. Rhode Island and Oregon have similar life expectancy numbers (79.8 and 79.7 years respectively);5 and mortality rates (713.4 and 717.2 respectively).6 Yet, the two states could not be more different: they are located on opposite coasts and do not share similarities in geography, population size, or weather. The statistics of certain states are so disparate, however, as highlighted by Hawaii versus Mississippi, (or West Virginia, or Alabama) for example, that it raises many questions, the most important being: why are some states healthier than others?

We look to public health to explore this question. So what is public health? Public health is what a community does to establish conditions that allow its members to lead long and healthy lives.7 It is primarily concerned with situations where large numbers of people die for preventable reasons or suffer from preventable causes.8

Our quest would not be complete without looking at state laws. Law is widely used for ordering, permitting and forbidding action,9 which invariably establishes the conditions in which we live as members of society. Public health law, more specifically, is concerned with the structural and rights-based limitations on the powers of the government to act in the interest of communal health.

There is no uniform code for public health across the US. States have thus independently created their health laws and amended them over time, creating a patchwork of differing mandates and permissible actions across the nation. This provides the best lens through which to study possible causes of health disparities.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt is credited with saying that “The success or failure of any government in the final analysis must be measured by the well-being of its citizens. Nothing can be more important to a state than its public health; the state’s paramount concern should be the health of its people.”

With this in mind, over the next few weeks we will look at specific topics one would expect to find in state health legislation, and observe how and if any particular issues correlate with states showing higher life expectancy and lower mortality rates.

The life expectancy and mortality rates of certain states are so disparate that it raises many questions, the most important being – why are some states healthier than others?

Ifedolapo A. Bamikole Tweet

[1] Kristen Lewis & Sarah Burd-Sharps, The Measure of America 2013-2014, MEASURE OF AMERICA (June 19, 2013), https://mk0moaorgidkh7gsb4pe.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/MOA-III.pdf.

[2] Id.

[3] Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Number of Deaths per 100,000 Population, KFF (May 15, 2019), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/death-rate-per-100000/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[4] Id.

[5] Kristen Lewis & Sarah Burd-Sharps, Supra note 1.

[6] Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Supra note 3.

[7] Lawrence O. Gostin & Lindsey F. Wiley, Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint 4 (2016).

[8] Lenny Bernstein, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy Wants to Move U.S. Health Care Toward a “Prevention-based Society”, Washington Post (April 23, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2015/04/23/surgeon-general-vivek-murthy-wants-to-move-u-s-health-care-toward-a-prevention-based-society/?utm_term=.3e9b06d9dfaf .

[9] Law, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

More from Ifedolapo A. Bamikole here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.