Ratna H. The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted a severe healthcare staffing shortage. HPHR. 2021; 33.

DOI:10.54111/0001/GG8

The COVID-19 pandemic has successfully highlighted the shortcomings within the U.S. healthcare system.

To address healthcare staffing shortages. If no attempt to address healthcare staffing issues is made, then the U.S. healthcare system risks collapse when it faces its next pandemic.

By 2025 the United States will face a shortage of 446,300 home health aides; 98,700 medical laboratory technologists and technicians, 95,000 nursing assistants, and 29,400 nurses.2 There will be a projected physician shortage between 46,900 and 121,900 physicians by 2032.

The federal government should strongly consider subsidizing the cost of healthcare education to alleviate the cost burden placed onto the students and incentivize a career in healthcare.

The federal government should finance more residency training positions so that more medical applicants can be placed.

The COVID-19 pandemic has successfully highlighted the shortcomings within the U.S. healthcare system. It highlights people’s lack of access to care and the need for universal insurance coverage. It highlights the need for supply chain contingencies so that disruptions in supply delivery do not lead to inopportune shortages. However, I would like to address healthcare staffing shortages.

Even prior to experiencing a pandemic looming overhead, our healthcare system did not employ staff in the numbers required to meet the demand. An indicator for the strong demand for healthcare workers, as tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS), is the increasing gap between filled healthcare positions and available healthcare positions. Since 2014, there has been a rise in job openings that healthcare systems have struggled to fill. This can be attributed to many factors, including the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the retirement of Baby Boomer healthcare practitioners as well as an aging population with an increased prevalence of chronic diseases. For the period of 2016-2026, the U.S. BLS projects an additional 1.26 million total healthcare job openings per year. This figure includes 624,000 healthcare practitioners and technical staff openings per year and spans a wide range of training plus salary levels.1

According to a 2018 report by the healthcare staffing consultancy group, Mercer, by 2025 the United States will face a shortage of: 446,300 home health aides; 98,700 medical laboratory technologists and technicians, 95,000 nursing assistants, and 29,400 nurses.2 In addition to this, based on 2019 data published by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), there will be a projected physician shortage between 46,900 and 121,900 physicians by 2032.3

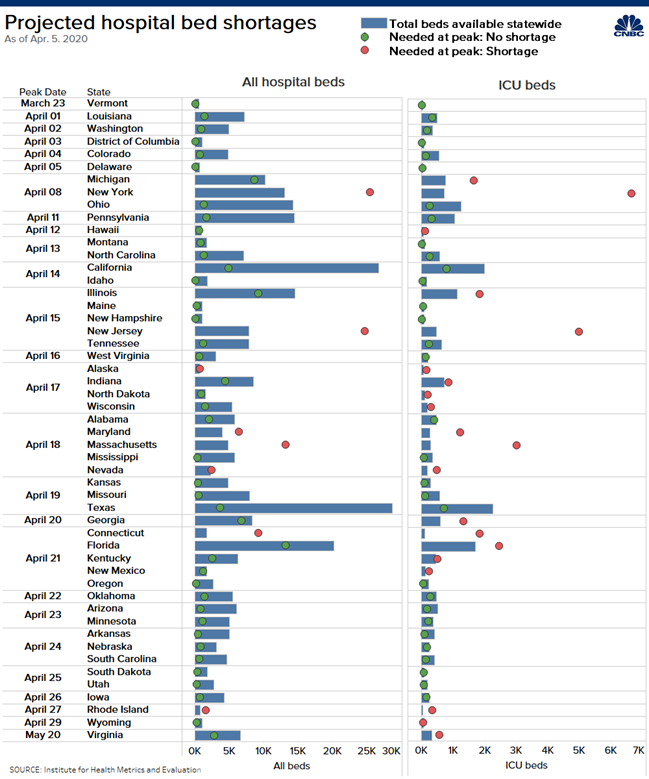

The acute onset of COVID-19 exponentially heightens this demand. Practices such as “social distancing” are meant to slow down the spread of the virus to avoid overburdening the healthcare system within a short period of time. However, methods to “flatten the curve” are not foolproof and are only as strong as the public’s adherence to mitigation recommendations. If the number of patients increases yet the number of providers stays the same, then each provider will be forced to take on more patients. And as the ratio of patient-to-provider increases, less time will be dedicated to each patient and the quality of patient care will suffer. The figure below highlights total hospital bed shortages and ICU bed shortages per state as of April 5, 2020.

Because of staffing shortages, healthcare workers must work longer hours and forgo more vacation days than virtually any other industry. Some reports have even shown that healthcare workers have been required to use their sick leave if they were needed to self-quarantine due to coronavirus exposure.5 However, if workers do not have sick leave saved up, they are forced to show up to work. Consequently, they will potentially expose their colleagues and patients to the infection.

If forced to burn the candle at both ends, workers will become exhausted and commit lapses in inpatient care. In 2018, the hours worked by healthcare workers reached a record high from the time data began being tracked in 1990. Hospital workers reached an average high of 37.1 hours worked weekly between February to June 2018.6 This value is likely to only have increased since the COVID-19 pandemic onset due to the aforementioned increasing patient-to-provider ratios.

A 2019 study published in The Journal of Nursing Administration linked nurse understaffing to an increased risk of healthcare-acquired infections.7 These infections would traditionally include pathogens such as Methicillin Resistant Staph Aureus (MRSA), Clostridium Difficile, and Pseudomonas. However, in a ward housing Coronavirus patients, the risk of Coronavirus spread is a cause for concern as well.

Exhaustion will also lead to avoidable healthcare spending. An analysis published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimates the cost of physician burnout to be $4.6 billion. This is a conservative estimate that includes:

The study did not include measures such as:

The COVID-19 pandemic has likely only heightened issues of healthcare worker burnout.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire need for increased healthcare staffing to meet the demand of the U.S. population. There needs to be a greater push to train new healthcare workers. The most expedient way to increase enrollment in healthcare schooling would be to alleviate the cost burden placed on the students. Getting a healthcare education quite often requires students to take out several hundred thousand dollars in debt in order to finance it. The federal government should strongly consider subsidizing the cost of healthcare education. Employment as a healthcare provider should be analogous to how the government treats military service because it is the first line of defense against public health threats. Consequently, healthcare providers need something analogous to the GI Bill (Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944) to help finance their education.

The threat of COVID-19 infection might deter people from seeking a career in healthcare. In addition to the aforementioned cost incentives, the federal government must address supply chain issues as well in order to ensure that the healthcare workforce does not face future shortages in personal protective equipment. The threat of infection is less concerning once healthcare workers are able to take adequate precautions.

Hospital systems must also re-evaluate their traditional staffing ratios and hire more staff. This may require a pay cut in order to accommodate more staff on the payroll. Staff should be encouraged to unionize and engage in collective bargaining in order to reach reasonable solutions with management. Staff is likely to resist any form of a pay cut so management should be prepared to bring adequate incentives to the negotiating table.

Hospital networks have tried many short-term fixes to address staffing concerns. One fix is to hire more non-physician practitioners (namely nurses and physician assistants) in order to compensate for the lack of physicians on staff. There is nothing particularly wrong with this strategy as long as there is a physician supervising the care provided by these non-physician practitioners. Unfortunately, this practice can also serve as a double-edged sword and can be exploited by management as a cost-cutting maneuver. If hospital networks rely on this practice too heavily to cut costs, there is the potential to undermine patient care provision.

A short-term fix that originated during this current COVID-19 pandemic is the practice of graduating medical students early and having them begin their residency training early. This practice is hardly foolproof either. Graduating medical students early ensures that they do not finish their curriculum in its entirety and poses a patient care risk. Adding more bodies to intercept patients doesn’t mean a whole lot if they’re under-prepared to meet the task.

A better move would be for the federal government to finance more residency training positions so that more medical applicants can be placed. During the 2020 residency match cycle, while 93.7% of American medical graduates were placed in residency training slots, only 61.1% of international medical graduates (a number that includes U.S. citizens) were placed in residency training slots.9 Unlike the early graduates, these applicants have fully completed their medical curriculums. However, their talents have been squandered, and have been left with no recourse but to apply again next year.

Our healthcare system isn’t static and contains many moving pieces. Even if fixes are implemented at one end, problems are likely to arise at another. For example, expanding healthcare access will only heighten the demand for additional healthcare workers. However, this doesn’t change the fact that healthcare access and healthcare staffing still need to be addressed.

In New York State alone, more than 40,000 healthcare workers have volunteered to be part of the state’s surge healthcare force. The COVID-19 pandemic has truly showcased the passion and dedication of the U.S. health workforce. However, the U.S. cannot hope to maintain a sustainable system on retirees and students alone. If no attempt to address healthcare staffing issues is made, then the U.S. healthcare system risks collapse when it faces its next pandemic.

Table 1: Projected Hospital Bed Shortages

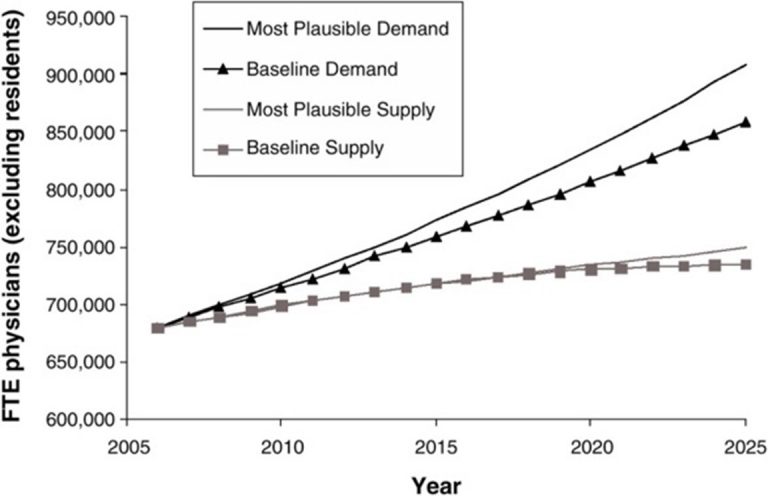

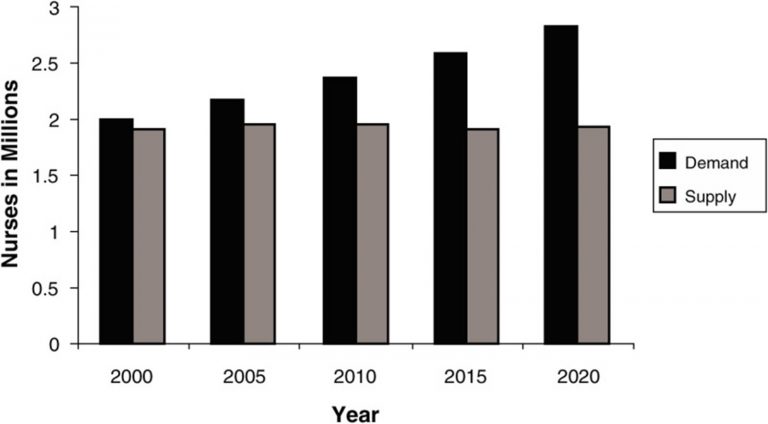

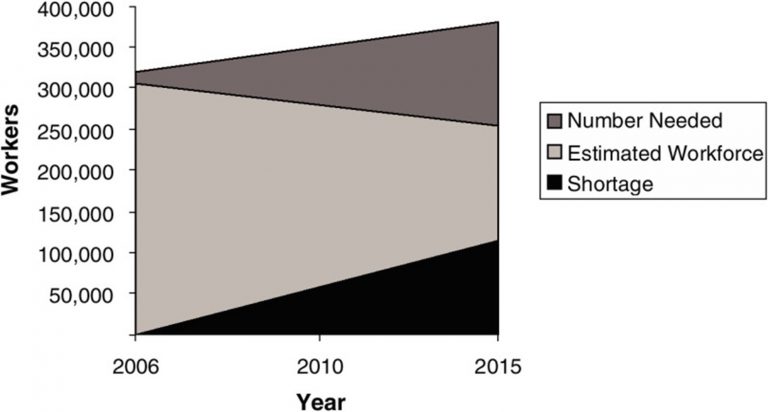

The following figures are sourced from “Ensuring Quality Cancer Care through the Oncology Workforce Sustaining Care in the 21st Century; Workshop Summary.”4

Haran Ratna, MD, MPH is a second year internal medicine resident at James J Peters Bronx Veteran’s Affairs. Ratna is the author of the piece, “The Importance of Effective Communication in Healthcare Practice,” which appeared in HPHR, Edition 23, 2019.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.