Mariyam D, Govind S, Goswami K, Kapoor K, Chakraborty S. Mental Health Helplines in India during COVID-19: a population-based survey to determine the efficacy and accessibility among Indian youth. HPHR. 2022;62. 10.54111/0001/JJJ5

In early 2021, India faced the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to an alarming rise in COVID-19 cases and related deaths. The mass grief resulting from loss and death has had widespread, immediate and long-term impact on mental health across the age spectrum, disproportionately affecting the younger population.

The primary objective of our study was to determine the extent of accessibility to mental health helplines among young people across India. Age was divided into two categories, for the purpose of the survey: under 15 years, 16-24 years and 25-30 years. Secondary objectives were to determine the level of awareness of existing helplines, self-perceived challenges or barriers to accessing mental health services and also to analyze the factors affecting access, specifically among young Indian healthcare workers.

A cross-sectional, population-based survey method was adopted. The survey was advertised and circulated via two social media platforms frequented by Indian youth: WhatsApp→ and Instagram→. The questionnaire was divided into 4 sections to collect general demographic details, mental health helpline usage, and accessibility among the general Indian youth as well as in young healthcare workers.

We received a total of 1,172 responses, of which 405 were from healthcare workers.

60% of the respondents did not feel the need to approach a mental health professional for aid. A majority (87.7%) of young people had never consulted a mental health professional or service provider before the onset of the pandemic. 59% of respondents were informed about the existence of various mental health helplines via the internet/social media. Among the youth that had sought mental health helpline services, 13.5% used a national helpline, whereas 8.7% used state/regional level helplines. 64.9% of young healthcare workers denoted lack of time to be a major barrier to the access of mental health aid, despite the existence of helplines.

The findings from this study highlight the need to formulate more youth-inclusive policies which ensure the coverage of, and accessibility to equitable mental health services for young people not just in India, but also in other similar low-and-middle-income countries.

Acknowledgment of the burden of mental health-related illness has increased in India.¹ Dr. Brock Chisholm, the first Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), in 1954, emphasized that “without mental health, there can be no true physical health.” Opinions have not changed substantially since that time. As global healthcare systems work towards the advancement of mental health worldwide, it has become imperative to understand the current scenario in India. In 2017, 197.3 million Indians (14.3% of the total population) suffered from various mental illnesses. Of these, 45.7 million had depression and 44.9 million had an anxiety disorder¹. These numbers, however, do not include those unable to seek medical care due to the stigma associated with mental illness or the lack of available services. An alarming number of young people in India with mental health issues are in need of care. According to the National Mental Health Survey, there is an estimated 9.8 million adolescents aged between 13–17 years who need active mental health care intervention.2 This leads to discussion on the urgent need surrounding available and accessible mental healthcare services for the youth of India.

In 2021, India faced the second wave of the pandemic which led to an alarming rise in COVID-19 cases and related deaths. Several state governments reinstated stringent lockdowns. This was coupled with the mass grief of loss and death, which the majority of India, especially young India, continues to deal with even to date. Evidence from early literature shows that lockdown-associated difficulties and isolation have had widespread immediate and long term impacts across the age spectrum, disproportionately affecting younger populations. ³ This study also focuses on young people in the healthcare workforce. Nearly two-thirds of the healthcare workforce in India is below the age of 40, with 25% belonging to the below-30 age category.⁴. Since such a large population of the health sector in India is driven by young people under 30, working on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is essential to document their experiences with accessibility to mental health services.

Social isolation and COVID-19 related cognitive preoccupation, ⁵ worries and anxiety can lead to negative psychosocial consequences⁶ among young people. With social media, the Internet, and transition to majorly online platforms becoming increasingly common for Indian youth, for the purpose of education, productivity, and even humanitarian aid during the healthcare crisis of the second wave, there is wide scope for the use of telehealth and online mental health services for young people, especially in the form of mental health helplines. Anticipating a surge in mental health issues and suicides during the pandemic, the Government of India (GoI) launched ‘Kiran (nationwide toll-free contact: 1800−599-0019),⁷ the first multilingual, national, toll-free helpline to respond to mental health crises. Similar helpline numbers run by various institutions, not-for-profits, charities, non-governmental organizations, initiatives, and corporates exist⁸ and are being used widely in India. Although existent, there have been recent instances of helpline numbers being inactive and unresponsive, ⁹ which is extremely concerning, especially in cases of suicide prevention and situations of heightened distress. Hence, it becomes imperative to check the efficacy, accessibility, and legitimacy of such mental health helplines used by youth amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, in India.

A survey was launched in May 2021 to collect cross-sectional data from any young person

belonging to the age groups under 15, 16-24 and 25-30, by two youth-led not-for-profit organizations registered under the Indian Trusts Act of 1882 – the Youth Centre for Global Health Research (YCGHR) and South Indian Medical Students Association (SIMSA). It was an online, non-probability/non-random sampling, single-phase study. The survey remained open from May 10, 2021, until June 21, 2021, corresponding with the peak of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in India. The survey was circulated via telecommunication to a network of volunteers who verified and collected data through two social media platforms frequented by Indian youth i.e., WhatsApp and Instagram. All responses were collected by standard means via a Google form. The background of the form consisted of a brief description of the aim and objectives of the survey, the World Health Organization definition of “mental health” and notified responders to not perceive participation in the survey as any form of mental health advice/ diagnosis. Links to other resources in support of the conversation surrounding mental health during the pandemic were provided for participants to gain further context of this study. Results obtained were only accessible to the investigators and no data were shared with or distributed to any third parties. Participation in the survey was solely based on consent through the online form and all data obtained were deidentified.

The survey questions were independently developed by the authors and divided into various sub-themes with the aim to discern the overall impact of the pandemic on the mental health of young people, accessibility to mental health services and included questions specifically for young healthcare workers. The questionnaire was reviewed by two senior professionals with 15 years of experience working in mental health care in a tertiary setting. Revisions were made based on the feedback received, to improve the adequacy, relevance and adherence of the questionnaire to the ethical standards of data collection from minors. The senior professionals also ensured that the survey questions were generalized and not diagnostic for any specific mental health condition.

Our survey collected a total of 1,172 responses, from all the 4 regions of the Indian subcontinent.

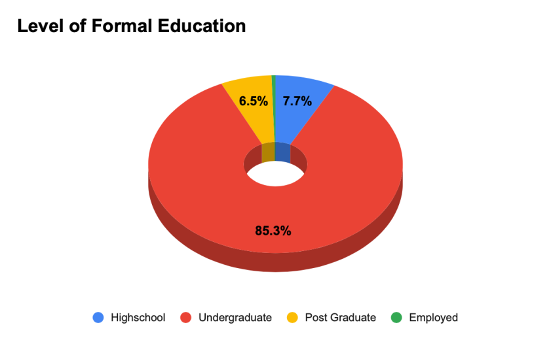

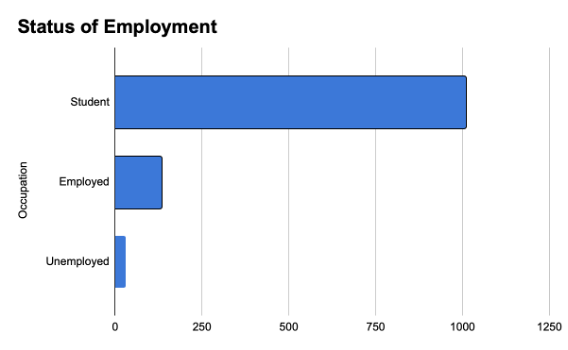

90% of the respondents belonged to the 15-24 age category. 8.7% respondents were aged between 24-30 and the remaining 1.3% represented the under 15 age group. 59.8% identified as females, 38.2% identified as males and 1.9% of the respondents preferred not to disclose their gender identity. 80.7% of those who took the survey had completed formal undergraduate education (bachelor’s degree). 6.4% of respondents were enrolled in some form of graduate study at the time of taking the survey, and 67. % were in high school. (Figure 1). Majority of our respondents were students (86.1%), 11.1% were employed and 2.1% were unemployed. (Figure 2)

Figure 1: Pie-chart distribution of the level of formal education (n=1172)

Figure 2: Occupation

Almost half our respondents (47.5%) believed that their mental health had deteriorated since the start of the pandemic, 21.9% disagreed, and 29.9% were undecided. When asked to self-report by rating their current mental state on a scale of 1-10 (with 1 being the worst score and 10 being the best), 20.3% (n=236) rated 8/10. This was followed by 19.3% (n=224) rating their mental state 7/10, 14.5% (n = 168) rating 5/10 and 14.3% (n=166) rating 6/10.

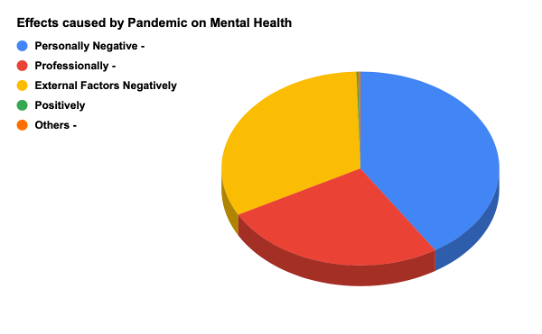

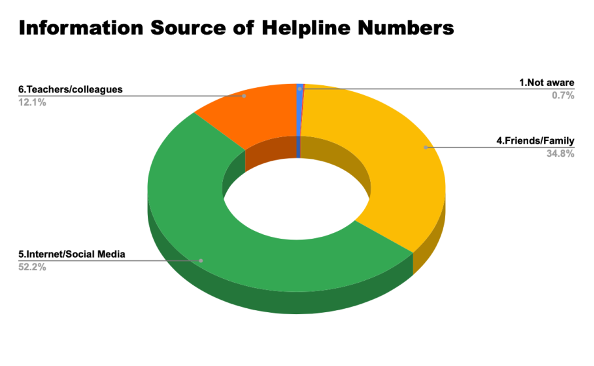

When asked what changes in their lifestyle the pandemic had brought forth, which might have an impact on mental health, 67.9% (n=777) respondents attributed it to increased stress due to academics, career and professional life. 65.6% (n=750) attributed it to reduced interaction with peers, 55.9% (n=640) attributed it to feeling of doom when concerned with the future and 30.2% respondents attributed it to the loss of a loved one, or their poor health. 52.2% (n=346) of the respondents had sourced helpline numbers from social media and the internet. Other significant factors described were financial instability (19.3%), being a caregiver for some with COVID-19 (14.2%) and domestic violence (4.5%). (Figure 3)

Figure 3. In what way(s) has this pandemic changed your lifestyle, that might be affecting your mental health?

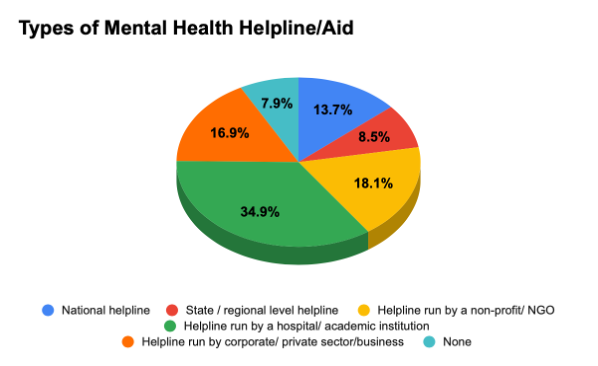

During the pandemic, 86.5% (n=1002) respondents never tried consulting a mental health professional or service provider through teleconsultation/ helplines. Only 118 (10.2%) respondents availed such services. Before the onset of the pandemic 87.7.% (n=1015) respondents had never tried consulting a mental health professional or service provider, whereas 9.9% (n=115) had, and 2.4% (n=28) preferred not to disclose this information. When asked whether they had ever felt the need to contact a mental health helpline for aid 66.7% (n=770) responded with ‘No’, 27.9% (n=322) responded with ‘Yes’ and 5.5% (n=63) preferred not to disclose. 70.1% (n=808) respondents were aware of the existence of helplines, 22.4% (n=258) were unaware and 7.5% (n=86) were unaware. Only 503 participants answered when asked what kind of mental health helpline/aid they had consulted with, out of which 34.2% (n=172) had used one run by a hospital/academic institution. This was followed by helplines run by a non-profit organization (17.9%) and helplines run by the corporate or private sector (14.9%). Only 13.5% (n=68) consulted with a national helpline. (Figure 4)

Figure 4. If yes, what kind of mental health helpline/aid have you consulted with?

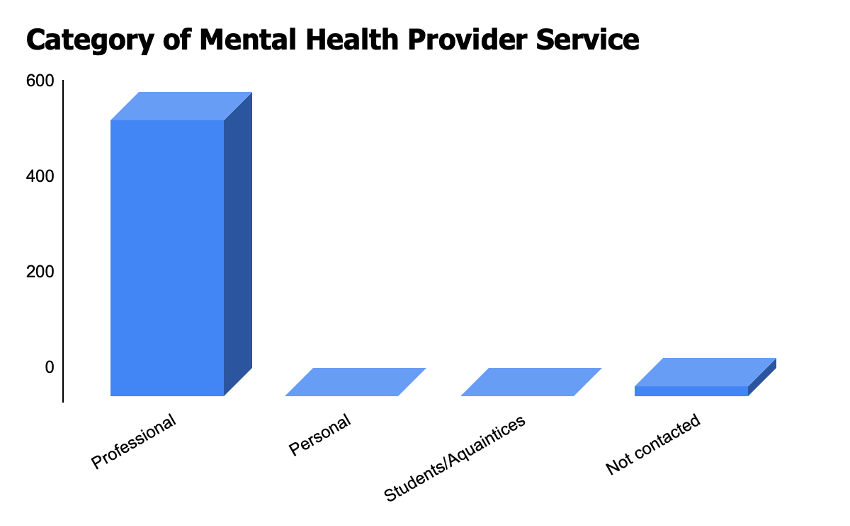

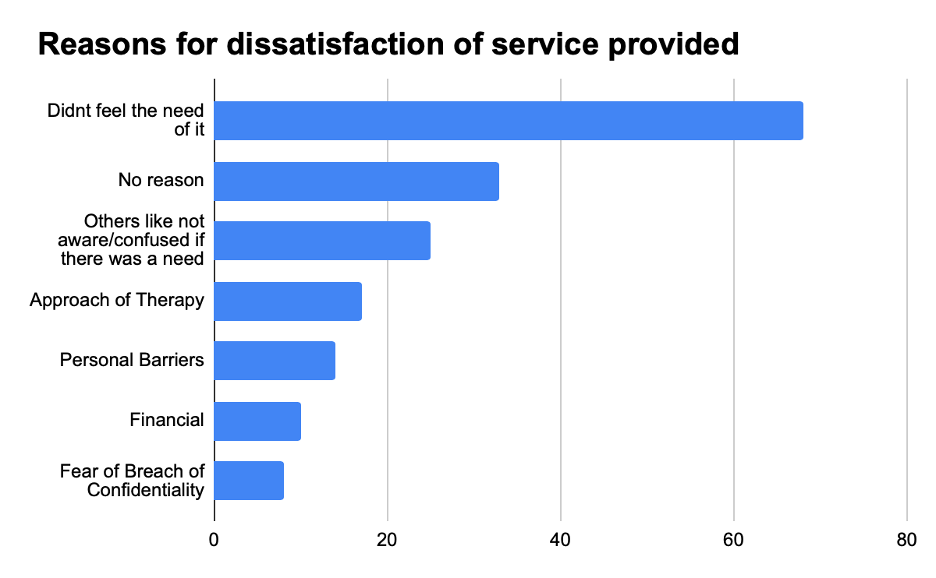

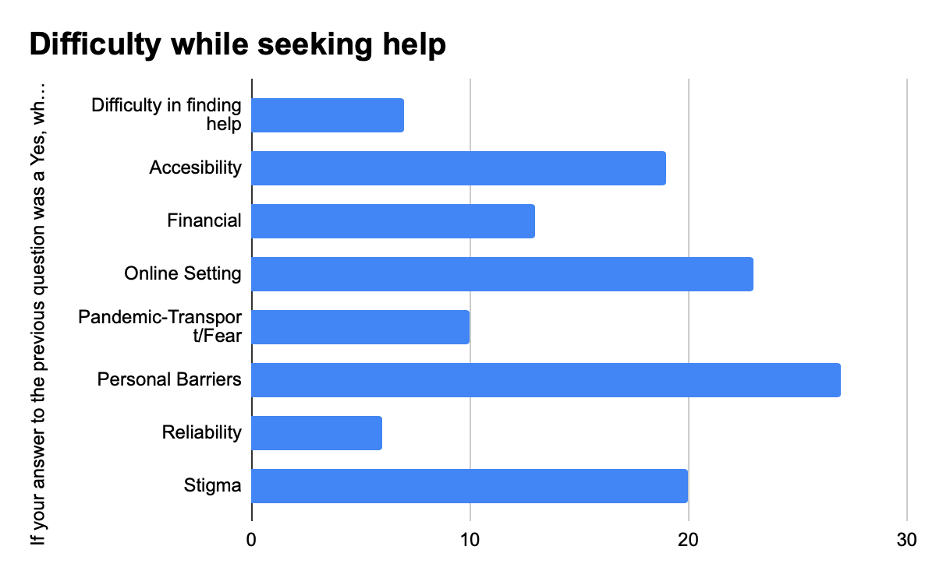

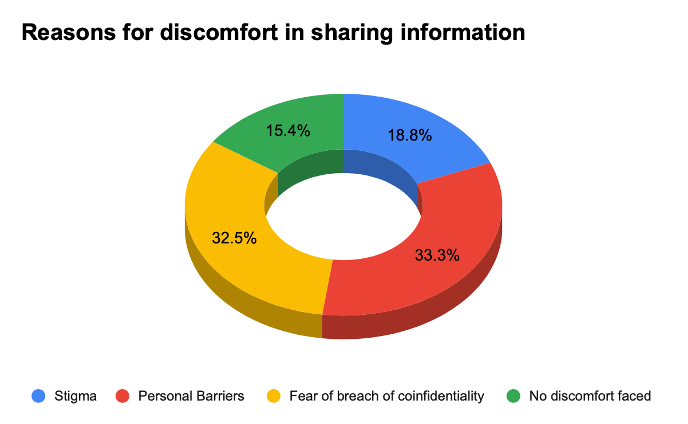

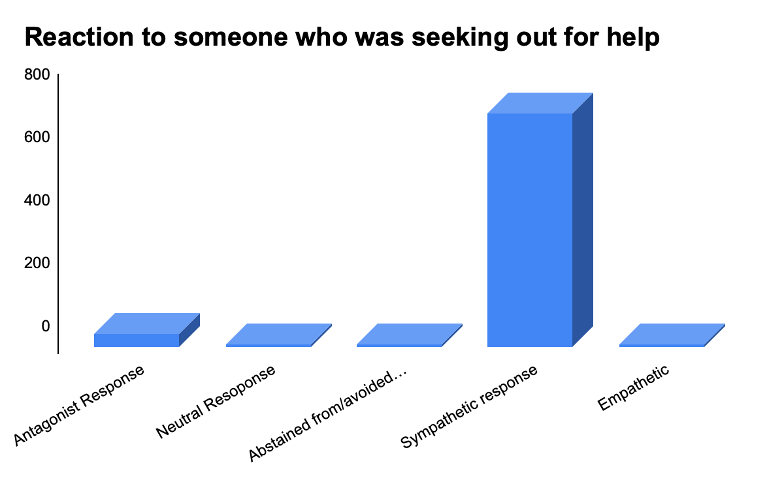

Out of 783 respondents, 59% (n=462) declared that their source of information regarding helplines was from the internet or social media, 36% (n=282) from friends and 22.6% (n=177) from digital/ print media. Only 599 participants responded to the question on what category of mental health professional they had contacted. (Figure 5). A majority (28.7%), had consulted with a counsellor, followed by psychiatrists (21%), psychologists (16.9%) and 16% from a therapist. 13.5% respondents had sought help from a professional but were unsure of what category they would fit under. (Figure 6). 525 participants responded to when asked whether they were satisfied with the help they had received. Out of which, 47.7% responded positively, 11.8% said no, 26.5% were unsure and 14.3% preferred not to disclose. (Figure 7). 62.9% (n=618/983) participants did not find it difficult to receive mental health aid amidst the pandemic, whereas 23% (n=226/983) found it difficult and 14.1% (n=139) preferred not to disclose. (Figure 8).1112 participants responded to whether their mental health had had an impact on their performance at the workplace or in their academic/ professional life. A majority (69.1%) believed that mental health issues had had an impact, whereas 17% were unsure and 12.6% denied. 63.5% (n=688/1084) respondents did not find it difficult to ask for help due to stigma, whereas 31% did, and 5.5% did not disclose. Respondents were asked to rate the extent of perceived support with mental health from their environment on a scale of 1-5 (with 1 being the least and 5 being the maximum level of support). Majority of the respondents (33.8%) rated their level of support to be 3/5. This was followed by 28.3% participants rating their level of support at 4/5 and 21.4% rated their support at 5/5. When asked to rate accessibility to cost-effective services for mental health needs on a scale of 1-5 (with 1 being the least cost-effective and 5 being the most), majority of the respondents (36.1%) rated 3/5. This was followed by 22.2% rating accessibility to cost-effective services 4/5. 68.1% (n=708/1040) respondents stated that they were comfortable sharing their identity with a mental health care provider, whereas 18.2% (n=182) were not, and 13.7% (n=143) preferred not to disclose. (Figure 9,10)

Figure 5. From where/what source(s) did you find out about the helpline?

Figure 6. If yes, which category would they fit best in

Figure 7. If yes, were you satisfied with the help you received? If your answer to the previous question was a No, kindly state the reason(s) below

Figure 8. If your answer to the previous question was a Yes, what is the major difficulty you’ve faced in receiving the aid?

Figure 9. If you answered no to the question above, kindly share the reasons for your feeling of discomfort. Note: These will be kept anonymous and confidential.

Figure 10. If Yes, how did you react to the situation? (when someone expressed the need to seek aid with mental health)

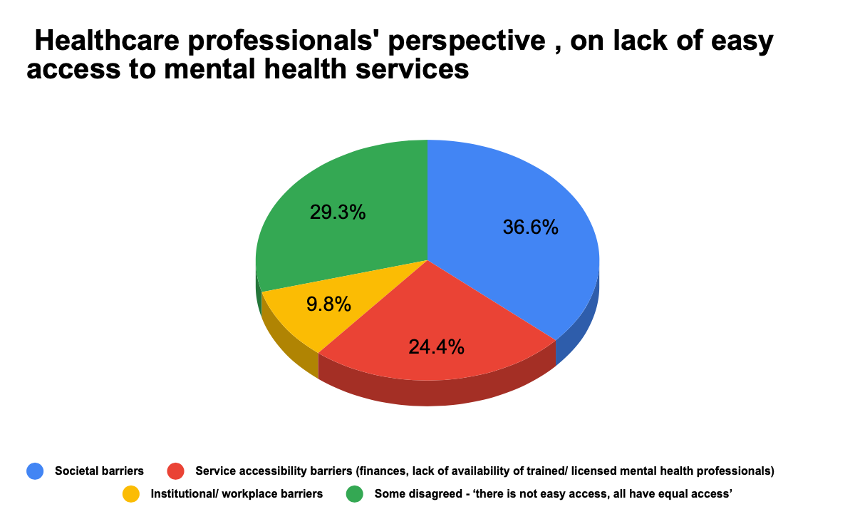

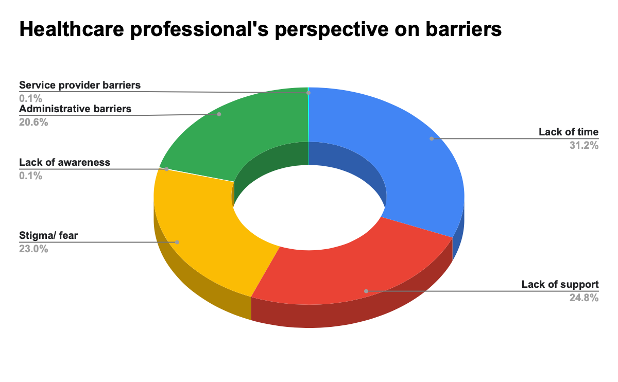

35.8% (n=420) of the participants surveyed were healthcare workers. A majority (73.1%) of healthcare workers stated that they had easier access to mental health services. 64.9% (n=259) frontline/ healthcare workers attributed to lack of time being the major barrier to using mental health services. (Figure 11). This was followed by lack of support (51.4%) and stigma (47.6%) being other major factors. (Figure 12)

Figure 11. If you answered no to the question above, why do you think that is? (mental health professionals having easy access to mental health services)

Figure 12. As a healthcare/ frontline worker, what according to you are the barriers faced by healthcare workers to accessing aid even though mental health helplines exist?

Mental health has always been placed at a low priority in health planning at the state and central levels in India, and this is well reflected in the quantity and quality of mental health service. There are only 0.75 psychiatrists per 100,000 population, a clear indicator of the country’s disinvestment in mental health service. ¹⁰

The majority of mental health services are concentrated in urban areas, and are primarily run by the private sector, creating an inevitable treatment gap. Past studies have addressed the exacerbated psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Indian population. Stigma remains is another factor which has also been heightened by the current crisis period. To address some of the treatment gaps, promising methods have been established, many of which include community-based, non-specialist, and tele-mental health programs. However, the pandemic has decelerated the efforts of mental health professionals, advocates, and several stakeholders involved in combating the inequalities and inefficiencies present in the adequate delivery of mental health services. ¹¹

Our results strongly suggest that the pandemic has had a significant negative impact on the mental health of young Indians, including young healthcare workers. The majority of survey respondents indicated lack confidence in mental health professionals and helplines, while others greatest barriers to the social inclusion of people with mental illness and delivery of treatment. Essential mental health services such as psychotherapy and clinical hypnotherapy sessions, usually done in-person, have been affected since the onset of the pandemic. This scenario has laid foundation for the delivery of mental health services via telehealth, which has resulted in poor rapport between the therapist and patient, problems with diagnosis, and lack of empathy. 11

Interestingly, from our study we found that the majority of young people intending to seek mental health services confided in helplines run by non-profit organizations, institutions or academic setups, over any national or state-wide helplines. This emphasizes the need for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) to work together with state governments and take effective steps towards increasing the visibility of government-run helplines among the youth. While young healthcare workers have comparatively better access to mental health aid, our survey suggests that they also face barriers to mental health care, including lack of time and stigma. Past studies have suggested several sociodemographic variables, including gender, profession, age, place of work, department of work, as well as psychological variables, such as poor social support, and self-efficacy are associated with increased stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms and insomnia in healthcare workers.12 COVID-19 poses as an independent stressor for healthcare and frontline workers who have had to, and continue to work for increased hours with high risk of exposure to the virus.

Our study found that a reasonably represented group of Indian youth when in need, will hesitate to seek advice from mental health professionals owing to stigma and societal barriers. The findings of our study resonate with the findings from a report published as part of the “Youth Bol: Making Youth Voices Count” campaign, supported by the Centre for Catalyzing Change (C3). This report published findings from 110,092 young people (aged 10-24) that were surveyed to understand their overall needs, right before the onset of the first wave of the pandemic. One relevant finding from the report was that young people, especially boys within 15 – 19 years, expressed the management, awareness and understanding of substance abuse and mental health to be a key area of concern. Mental health emerged as an imperative focus within the spectrum of health. Young people participating in the survey articulated an urgent need for access to more confidential, non-judgmental and affordable mental health services.¹³

With increasing need, we urgently require a sturdy plan of action to ensure methodical disposition of the existing and future helplines to provide more accessibility, whilst assuring the quality of service being provided. The stigma associated with seeking mental health services also needs to be addressed through initiatives, such as awareness campaigns. A few other probable solutions could be to utilize social media for health education through outreach programs. With around 518 million social media users in India, various platforms can be utilized to circulate resources for mental health, provided reliable and trustworthy information is disseminated.

This study has strengths and several limitations. To our knowledge, and based on the current literature, this is the first population-based survey focusing on young people and their experiences with access to mental health helplines. We highlight the experiences of often-overlooked young healthcare and frontline workers in the context of their usage of and access to essential mental health services/helplines. The population we surveyed is representative of various subcategories of age, gender, and geographical situation among the young demographic of India. Additionally, we contribute to the current literature by bringing out emergent themes that act as barriers to the accessibility of mental health helplines and services among the Indian youth. One of the major limitations of this study is that our sample size is small when compared to the entire demographic of Indian youth, and hence our results must be interpreted with caution, avoiding generalization. We have not statistically computed correlations between geographical location, educational qualification/status, and age or gender variables to factors hindering accessibility, which has significant scope for future research. Finally, our study does not use standardized outcome measures/ questionnaires for the evaluation of impact on mental health. It is merely a self-perceived assessment and hence is not a true indicator of any mental illness and/or psychiatric diagnosis among the Indian youth.

Lack of mental health care is widespread in India. A study¹ published in the Lancet reveals that in 2017, 14% of India’s populace suffered from mental health illnesses and with the lockdown, the current situation has only worsened. Mental health helplines offer a solution to what can now be called an emerging mental health epidemic in India.14

Young people can drive long-term and practical mental health investment solutions. World leaders must invest in mental health, and young people are key stakeholders who will drive such interests. They provide vital insight on the need for inexpensive, accessible services in primary health care through unified discussions on mental illness. Petitions and outreach programs in educational institutes and revising the curriculum to incorporate mental illnesses can help build a more open-minded foundation to tackle the stereotype revolving around mental health.

The author has no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Dr.Deena Mariyam is a fresh graduate, who is passionate about achieving Universal Health Coverage. She considers herself to be an advocate for various social issues like mental health, climate change and gender equity. Her passion drove her to actively participate in NGO functions and now she is an active member of YOUNGO and several other constituencies.

Dr. Srihari Govind is currently a fellow for the Global Consortium of Climate Change and Health Education, with interests in global health, climate change, Disaster Risk Reduction and medical anthropology. In a volunteer capacity he is also serving as the Director of the Youth Centre for Global Health Research, a youth-led global health think tank.

Dr. Katyayani Goswami is an honorary scholarship recipient at Madras Medical College. She is an intern doctor and an aspiring Neurosurgeon. She strongly advocates for refugee rights and peace, and has been working on several projects, including driving ahead a trans-national activity on disaster medicine and refugee rights.

Komal Kapoor is a graduate from Christian Medical College, Vellore in an allied health science field. She is a strong advocate for the cause of mental health and has been working with several national and international organizations where she has provided her insights and views on the same. She has worked as a frontline COVID-19 healthcare worker at CMC, Vellore in the past. She is also a country representative for India from HIFA (Healthcare Information for All) and was responsible for highlighting the importance of mental health services as a part of a global Covid project in collaboration with WHO. Currently, she is working as a summer intern with a healthcare start-up backed by IIT Madras.

Stuti Chakraborty is a PhD student at the University of Southern California. Her contributions to the field of healthcare are specifically centered around research, raising awareness, communication and advocacy. She was selected as one of the 3 young persons on behalf of the United Nations Major Group for Children and Youth to represent India at the Global Conference on Primary Healthcare, organized by the WHO and Ministry of Health of Kazakhstan, in 2018. She has represented her country at various occasions in the past, was one of the few people selected from India to attend the Harvard Medical School and MIT Healthcare Innovation boot camp in 2019 and is also currently a Harvard Public Health Review fellow for the 2021 cohort. Her major areas of work include raising awareness about the impact of disability on marginalized communities, young people and women. In the past, she has been an active contributing member of various youth-focused/youth-led organizations such as the Global Healthcare Workforce Network Youth Hub and Your Commonwealth

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.