As I have deepened my own understanding of public health, I have looked to the socio-ecological model. To explore the connections between sociology, the community, and health outcomes, I interviewed Dr. Mary M. Wesley, an epidemiologist who has focused her attention on maternal and child health and advancing public health research and education in Mississippi. I hope you find her answers as informative and illuminating as I did.

Claire: Could you tell me a little bit about yourself as a resident in Mississippi, and how that shaped your career interests?

Dr. Wesley: I was born and raised in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Growing up in Mississippi and the South, I had an interest in health, because of — what I didn’t know at the time were called — health disparities.

I saw differences in health experiences and health outcomes within my family and within my community. And one thing I’ve shared with students is that, I didn’t know at the time that these were things that could be changed with research and with policy, and I just sort of accepted them as a matter of fact — but I was bothered by it.

That’s where my interest in being in the field of health came. I saw very clear needs and I saw different experiences by different populations, and I wanted to help but I didn’t understand the broader impact of the environment and social determinants of health. That’s what got me interested, was seeing my experience and the experience of my community, and wanting to somehow help change things.

Claire: Could you tell me a little bit about your journey as a researcher and how you got involved in the work you’re doing now?

Dr. Wesley: Advancing from that awareness and desire to be a part of positive change, I decided to pursue health-related professions. I focused on life sciences in undergrad and went to Prairie View A&M, where I got interested in research through summer programs — which is why I’m so passionate about working with students now.

I decided to do a post-bac program at Tufts Medical Center and did lyme disease research. But it was there that I switched from basic science to more clinical research, and I spent two years there. During that time, I had a friend who was in epidemiology research. She was looking at depression symptoms among immigrants and the changes in diet that affected depression. And I was like, “woah, my world is changing.”

For me, I saw a practical application, and I saw a population I could serve. I saw her project, I talked with her, and that’s how I got interested in epidemiology. From there, I decided to do a Master’s in Public Health degree at University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) focusing on epidemiology. After staying at UAB for a year and working there, I taught science for two years.

The pitstop in education was really helpful for me because being a teacher (it was middle school, 7th grade), I really saw firsthand the impact of the social determinants of health. It was there. There was no denying it, and understanding all the different things that were impacting the kids and their abilities to perform — but also to just live good lives. That was a real eye-opener for me. It wasn’t that I hadn’t seen poverty or understood poverty, but I saw it population-wide, being in Mississippi and working in minority communities for Jackson public schools.

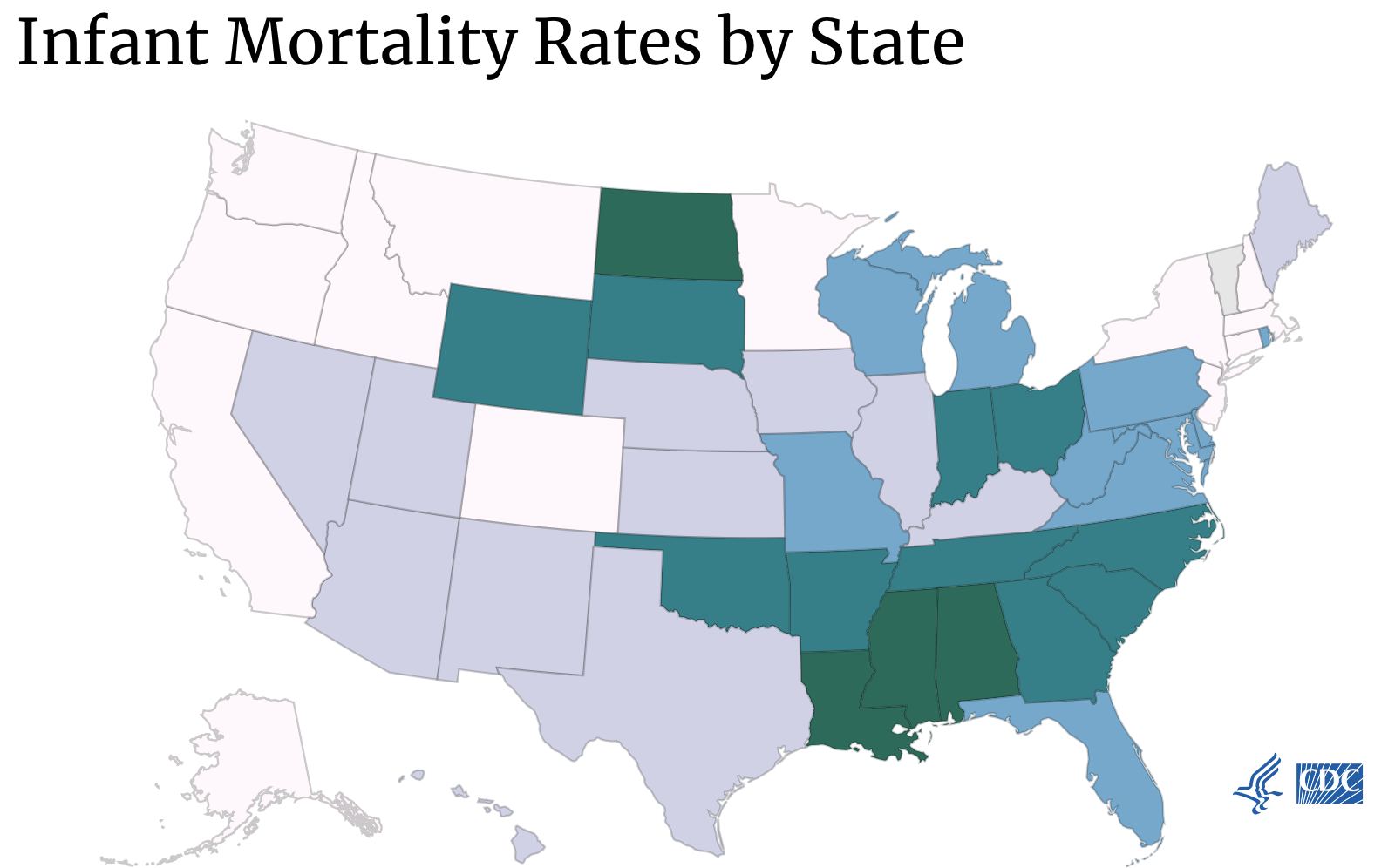

When I went to the health department and started working in Maternal and Child Health (MCH), that was a whole new field for me. I started doing the surveillance reports for MCH with PRAMS and birth outcomes, and I had no idea the disparities in infant mortality. A black baby is twice as likely to die in the first year of life compared to a white baby.

And I was like, “That makes absolutely no sense,” but I had already seen later on in social development as a teacher, all of the social determinants of health that were affecting the families and the communities around me. When I was then doing the surveillance reports at the health department looking at MCH, infant mortality really bothered me the most. That was the impetus for me getting the DrPH and moving on past the health department.

There was work being done, a lot of good work being done, and I wanted to be a part of that work. That’s why I wanted to pursue additional training and the DrPH. Within that, working at the health department, I saw a lot of good people doing a lot of good work with a lot of barriers, societal and structural, as well as a lack of resources. I don’t think people understand how much good work is being done in the state and in the region if they’re just looking at the outcomes and not understanding the input or the context for the problem.

That was a really nice understanding for me to take to the DrPH program and get the training in leadership to drive public health change. So I did that for four years and came back and ran PRAMS and data collection for the Title V MCH Block Grant. I did that for a year, and then this fellowship position (the Delta Scholars in Public Health Teaching Fellow) opened up.

Claire: You’ve done a lot of work with communities in the South on Maternal and Child Health. What are some of the unique challenges faced by these communities?

Dr. Wesley: Most of my work with the state Department of Health has been in Jackson and Mississippi. I think access to quality care: but by access I mean, thinking about all the factors that facilitate health-seeking behaviors of individuals, and the public health resources that are available.

With COVID, I would say maybe the one positive thing has been the attention on the importance of public health as a field, but also on public health infrastructure. When public health is done really well, it’s not at the forefront. Public health should be in the background providing infrastructure and support, but with the pandemic that we’ve been living through, it’s been at the forefront.

Claire: What are some of the unique challenges facing mothers and children?

Dr. Wesley: We know that disparities exist. One of the unique challenges is, because we’ve had disparities that have existed for such a long time, people can become complacent or just, sort of, lose confidence that things can change. I think part of it is due to burnout. I’ve seen this in the professional workplace, but also in the community. It’s really easy to be so over-burdened by everything that’s going on.

Historically, this has been what’s going on, but with COVID, there has been an understanding of the importance of public health and what’s going on. There’s been an energizing advocacy of people demanding change.

The other challenge is, there is a lot that’s known about health disparities and there’s a lot of good work being done, but there is so much more research that needs to be done to understand why the disparities exist, and why there are differences in infant mortality and in preterm birth, and the institutional and systems changes that can occur. This could be clinical research in a lab but also policy research. I just feel there’s a huge need for people to make an investment in public health research.

Dr. Mary M. Wesley is a proud native of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and currently is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Epidemiology at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

In this position, she serves as the Delta Scholars in Public Health Teaching Fellow. Dr. Wesley works with students, faculty, and organizations in the Mississippi Delta region and in the Harvard community to advance public health research, education, and practice in Mississippi.

Chapter 1: Models and frameworks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_models.html. Published June 25, 2015. Accessed September 10, 2021.

Stats of the states – infant mortality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/infant_mortality_rates/infant_mortality.htm. Published March 12, 2021. Accessed December 15, 2021.

More from Claire Bunn here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.