Previously on Screen the Lungs!¸ we took a look at the deep disparities in lung cancer health and outcomes across the US that have persisted over time.

Lung cancer screening (LCS) using low-dose CT scans (LDCT) remains our best opportunity to address these issues and potentially prevent hundreds of thousands of needless cancer deaths.

However, we learned previously that LCS has and continues to be severely underused and itself sees serious disparities in rate of use and patient accessibility, leading to exacerbated inequalities in lung cancer health.

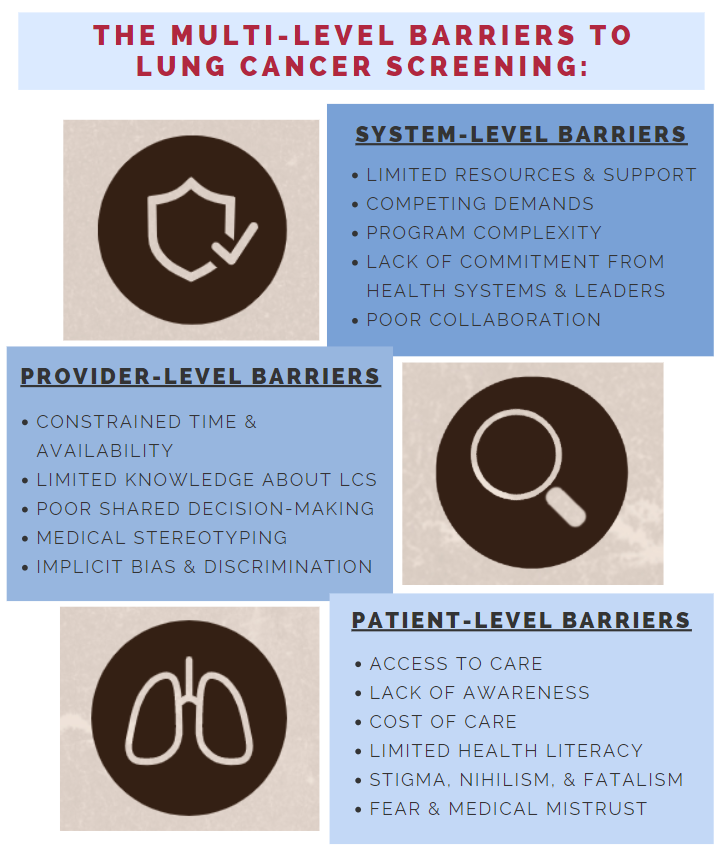

In this blog, we will take a broad look at the complex barriers – which exist at multiple levels of healthcare – that have challenged LCS implementation and prevented effective and equitable screening.

An informed decision to screen for lung cancer involves consideration of a diversity of factors including the risks and benefits of CT scans, follow-up procedures, false-positive rates, overdiagnosis, comorbidities, and patient preferences.

Limited health literacy and numeracy, especially among patients of lower educational background or SES, commonly challenge patient comprehension and informed decision-making.

These challenges are only exacerbated by the fact that the informational aids and resources for LCS that exist are highly inconsistent and, in many cases, inappropriate. The vast majority of patient-facing LCS resources are written for native English speakers and in more complex language than is recommended by the American Medical Association and National Institutes of Health, even further alienating many patients.

Geographic isolation and poor access to LCS-equipped health centers also serves as a barrier to many patients and creates sociodemographic disparities. Patients residing in rural communities are far less likely to have access to screening locations compared to patients in urban areas.

This geographic inverse care phenomenon is strikingly highlighted by the Southeastern US, which is one of the poorest regions of the nation, harbors a high concentration of Black Americans and other underserved minorities, and has the highest prevalence of smoking and incidence of lung cancer in the country. Yet, the region’s population has one of the lowest rates of access to equipped LCS services.

There also exist a diverse array of stigmas that are unique to lung cancer. Because of the direct association between smoking and lung cancer, many patients are likely to be blamed, or blame themselves, for their cancer. This presents a significant barrier to seeking screening services or treatment after diagnosis. Patients from minority populations are also very likely to face an exacerbated burden of stigma due to the other factors, marginalizing them even further.

Nihilism and fatalism among smokers and patients with a lung cancer diagnosis are also extremely prevalent. Many people see lung cancer as “death sentence”, which prevents them from engaging with the cancer care continuum. Furthermore, fear or mistrust of physicians and the healthcare system as a whole also poses a significant barrier to screening, especially among patient populations that have been medically marginalized throughout history.

Among the most influential patient-level barriers to LCS is cost of care. Because smoking is the most prevalent with Americans of low socioeconomic status, ensuring LCS to this population would actualize the most benefit out of screening. Yet, this obvious need is left overwhelmingly unaddressed. Over half of eligible patients are either uninsured or underinsured with state Medicaid programs, which are not required to cover LCS, and wide variations in coverage have persisted across the country.

Racial and ethnic minorities are even less likely to be adequately insured, and we have seen in these groups especially dramatic drops in screening rates when LDCT costs fell to the patient’s expense.

Because the considerations leading to a decision to screen are complex, physicians are expected to engage their patients in a shared-decision making process (SDM).

When utilized effectively, SDM is a very effective tool at increasing patient comprehension of the risks and benefits of screening, eliciting patient preferences, and reducing decisional regret. However, SDM has seen many challenges, particularly in the LCS process, that have created barriers to screening for many patients.

Only about 10% of Medicare patients undergoing LCS reported having been provided an SDM visit with their physician. Historically, the quality of most SDM visits for LCS has been revealed to be very poor. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that Black patients and other minorities are even less likely to be provided an appropriate SDM meeting than White patients.

Among the most cited barriers to SDM in the clinic include lack of time, misunderstanding of patient desires, lack of organizational support, and the fact that many provider are simply not aware of the option for or benefits of LCS.

Implicit bias and discrimination in racially or culturally discordant patient-provider interactions has been long demonstrated, including in oncology, and significantly compromises the cancer care process and alienates many patients already underserved in healthcare.

Stereotyping of patients that smoke by clinicians is also quite prevalent. Many providers today are too young to remember how common smoking was in previous generations, as smoking rates have declined dramatically in the past few decades. This disconnect between providers and patients compounds with similar issues of trust, perception, and stereotyping that alienate patients from care.

LDCT LCS is a very complex intervention at a high-throughput capacity. Thus, health systems can face significant burdens in building and maintaining a successful lung cancer screening program.

Given the high-touch trajectory from a decision to screen to clinical reporting and workup, strong and consistent multidisciplinary coordination across the health system is essential. Screening administration, analysis, work-up, data reporting, and other administrative demands require standardization and test health system infrastructures.

Such demands put an amplified strain on a health system when limited access to resources or competing demands within the system for funding start to crowd the table. CT scanners, specialists, IT infrastructure, and financial support are among the many factors that complicate program implementation, especially among smaller health systems and fledgling screening centers.

Indeed, smaller health systems and clinics designed to care for traditionally underserved communities, such as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Veterans Health Administrations (VAs), have consistently struggled to manage these many infrastructural and financial burdens of LCS. These challenges overall have widely discouraged and limited such clinics from committing to screening programs, leaving many American communities most vulnerable to lung cancer without preventive screening power.

The many diverse barriers that compound to challenge screening programs and patient access to care highlight the complexity of equitable LCS implementation, and explain the striking disparities that exist in screening, morbidity, and mortality for lung cancer.

Due to these challenges, many of the most vulnerable populations at risk for lung cancer have been largely alienated from LCS, augmenting the existing health disparities seen in marginalized groups of Americans.

It is paramount that accessibility and equity of LCS services must be prioritized as a primary pathway through which to lung cancer outcomes can be improved. Concerted and cooperative initiatives must be taken to address and overcome the many barriers to access that challenge equitable LCS.

Moving forward, Screen the Lungs! will take a much closer look at some of the most salient barriers across the patient, provider, and system levels that challenge LCS.

Leaning on the experiences of the people directly involved at each level and leveraging lessons learned from the implementation of other interventions, we will think about how we can act now to do better.

More from Brian Shim here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.