Hey there, thanks for dropping by. Whether today’s topic is new to you or something you are deeply passionate about, I hope my exploration will bring you new perspectives to ponder.

Feel free to listen to the blog’s recording below.

Long-term care (LTC) refers to services that provide support for someone unable to perform daily tasks independently and safely. According to the most recent data gathered in 2015 by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, over 1.3 million Americans reside in 15,600 nursing homes across the country. LTC services can also include hospice care, home support, and community services such as adult day centers, but for our time together, the term “long-term care” will solely be referring to nursing homes (US context) or long-term care centers (Canadian context).

The pandemic has had a devastating impact on LTC across North America. For a visual representation of the extent of the outbreaks, check out these two resources:

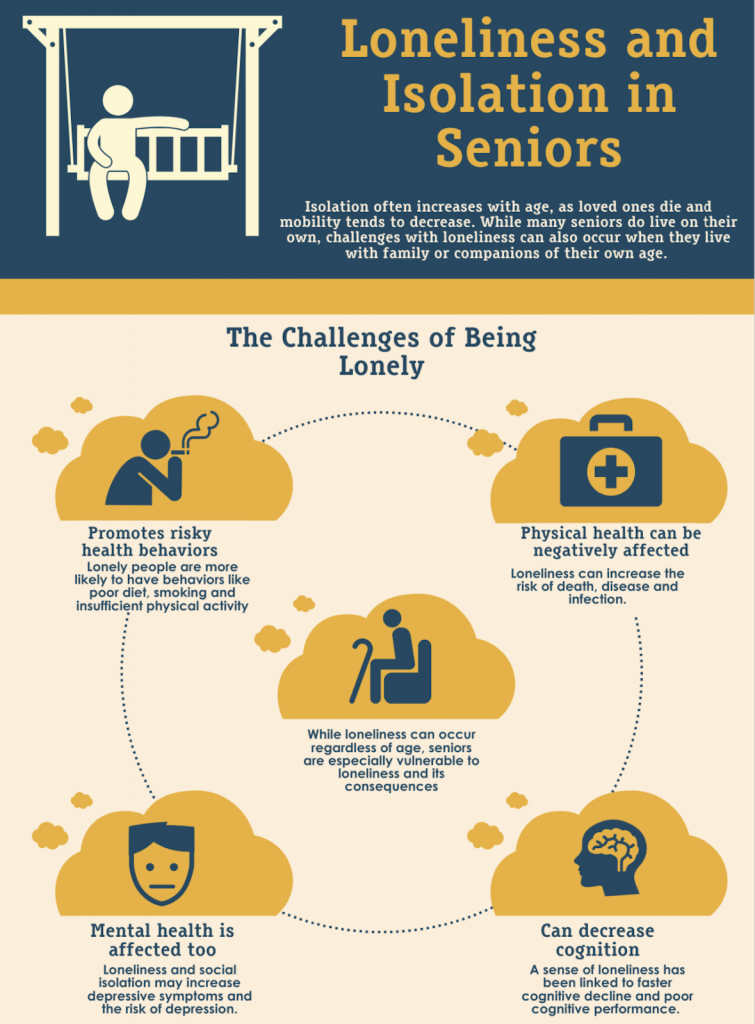

While physical distancing is an effective way to reduce the spread of COVID-19, it may have allowed a new epidemic to emerge, one that has been silently spreading for years – loneliness.

In 2017, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy cautioned of the dangers of loneliness. Today, Dr. Murthy’s warnings of how prolonged loneliness can trigger physical and psychological conditions among people of all ages continue to ring true.

Social connection has always been essential for survival. He argues while many aspects of our present-day have evolved since our hunter-gatherer times, “our nervous system…is very similar to what it was back then. And when we are separated from people, when we feel separated, regardless of how many people we have around us, we enter into a similar stress state.”

Multiple research studies conclude that social isolation is especially detrimental for older adults in LTC. Prolonged feelings of loneliness can increase the risk for the following –

Mental health

Physical health

Did you know, in America, LTCs are 8 times more likely to be found in zip codes with

a high percentage of older adults who live alone?

This first-of-its-kind geographic analysis of LTC confirms a much earlier study published in the 1980s that years of social isolation in the community may have contributed to some older adults requiring institutionalized care. The bidirectional relationship between social isolation and LTC remains complex and fluid.

To decrease the rate of COVID-19 transmission in LTC, public health officials implemented a ban on non-essential visitors (including families) across North America. In the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC) where I am from, this restriction lasted over 12 months. While public health measures are necessary to protect this high-risk population, isolation from loved ones fuels the loneliness epidemic.

By labeling families as non-essential, the system not only devalued the importance of their already unpaid labor but subsequently denied an integral part of the resident’s care team. At a time when the healthcare workforce is already stretched thin, family caregivers who can continue providing emotional support and basic care, in compliance with infection control protocols, can have positive effects on residents’ quality of life.

While providing outreach to LTC during the pandemic, I couldn’t help but notice the deafening silence inside some facilities. The social spaces that residents used to enjoy meals and activities now gathered boxes of masks and sanitizers.

I want to acknowledge the creativity that care teams have demonstrated to bridge social connection with limited time, resources, and public health guidance. Some leveraged technology such as video calls and others took advantage of available outdoor space for window visits. But for residents living with cognitive, visual, or auditory decline, communication through a barrier can be extremely challenging, sometimes even meaningless for engagement. Similarly, residents who are unable to communicate with staff in their preferred language are also less likely to transition to and benefit from alternative methods of connection.

The stories I have heard from care workers and administrative staff of their experience taking on the emotional burden and increased workload of fulfilling familial roles further highlight the cascading effect social isolation has on all those involved in the residents’ care. For some, it is a constant moral and ethical dilemma trying to enforce visitation policies (often at the risk of creating tension with families) while preventing the effects of increased loneliness and disconnection.

Social isolation has a dire impact on the physical and mental wellbeing of residents, puts pressure on care staff to take on additional burdens, and exacerbates the grief families feel for the time lost with loved ones. It is evident that no one is immune to the loneliness epidemic and our older adults in LTC continue to be the most at risk.

As Dr. Murthy alluded to, we can feel alone even if we are in a crowd. Public health must recognize the importance of residents’ preferred social network as a critical voice in the decision-making process for any future LTC policies.

Public health must recognize the importance of residents' preferred social network as a critical voice in the decision-making of any LTC policies.

Loneliness is an invisible threat that will linger beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, and continue to silently deteriorate the physical and emotional wellbeing of older adults if we do not pay attention to it now.

Before we part, I leave you with one final thought – if there is an important elder in your life, let this be your reminder to check in with them today.

Until next time!

Sherry

More from Sherry Wu here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.