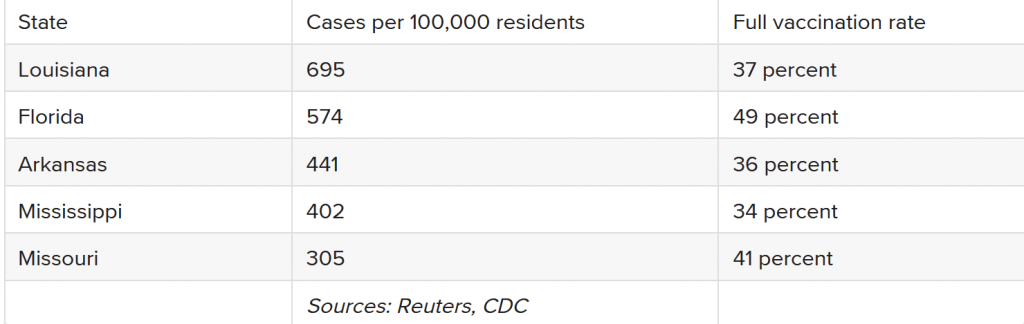

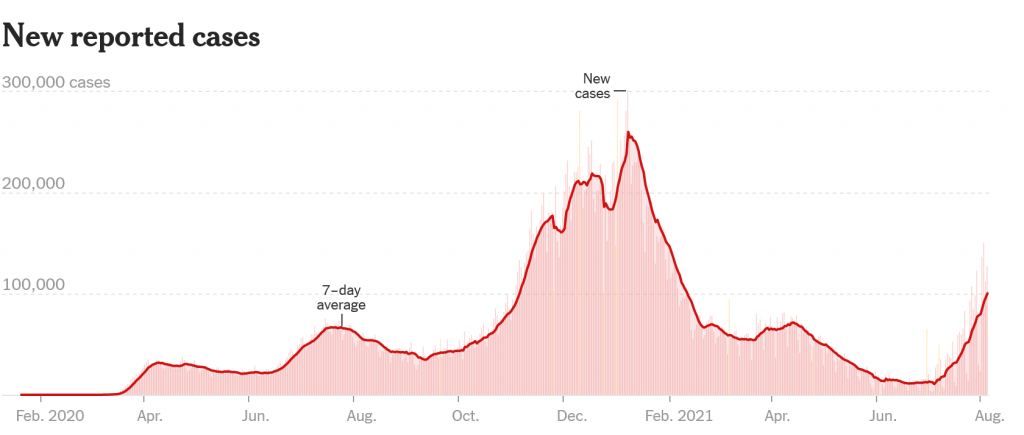

Covid cases are rising across the United States due to the transmission of the delta variant. The steepest increases have been in the South, where Florida, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina are dealing with the most extensive outbreaks in the nation. All of those states have rates of vaccinations below the United States average of 49.2%, with Mississippi and Louisiana being in the bottom five of the entire country. Experts are calling it the “pandemic of the unvaccinated.”

Source: New York Times

Vaccines are incredible scientific accomplishments that have significantly decreased rates of death and disease around the world. For example, the Pfizer vaccine is 88% effective at preventing severe illness with the COVID-19 virus caused by the delta variant. In addition, officials have made vaccines available at community health centers and pharmacies; some states are giving incentives to get more people vaccinated.

Yet, people do not want to take them even though the data are unequivocal about their effectiveness. For some people, it’s about choice and freedom to choose what goes inside their body, while others do not trust the government. Considering their effectiveness, governments should not have a problem getting people vaccinated in an ideal world, but we do not live in a perfect world. Data are not enough to change the behavior of people. A 2015 study found that when information was provided to people that refuted vaccine-autism linkage, it did not decrease anti-vaccination attitude. Our identities have become entangled with our opinions, which means we consider an attack on our views an attack on our belief system.

One of the reasons why conspiracy theories spring up with such regularity is our desire to impose structure on the world and incredible ability to recognize patterns. Indeed, a recent study showed a correlation between an individual’s need for structure and tendency to believe in a conspiracy theory. The decades-long decline in faith in the government and sharp rise in inequality has exacerbated the situation.

According to Yale Law School professor Dan Kahan, the views of people about ethics and the way society should be structured can strongly predict whom they would consider as a “legitimate” scientific expert. For example, in a classic 1979 experiment, pro and anti-death penalty advocates were exposed to two fake scientific studies. Comprehensive critiques of these studies were also given to the groups, yet advocates did not change their minds in either case.

Our value system is critical for our judgment. The way an argument is positioned can change our minds. If it aligns with our value system, we are more inclined to react positively. We can also call this “Confirmation bias,” which is the tendency to search for and favor evidence in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values.

People are more inclined to change their position about an issue when a message is delivered from someone within their social identity group. According to one recent study, Republicans who were initially hesitant about the vaccine were prepared to change their minds when receiving pro-vaccine messages from leading Republican figures. People are also likely to alter their opinion when they communicate with members of their social groups that have already changed their opinion about an issue.

Trust is one of the fundamental pillars when trying to convince an individual of something they do not believe. Unfortunately, when presented with data that undermines our beliefs, we stick with our beliefs and ignore the data. Social acceptance is vital for humans, and we have evolved to cooperate within our social groups, which makes us capable of justifying our beliefs. For that reason, fact-checking may not work, and people believe what politicians tell them. Research has shown it can backfire with people supporting these slips even stronger after fact-checking. The need to fit in a group was essential for our species. Without a group, a person would lose access to resources and protection. Acceptance in the group is more important to some than the accuracy of facts. Humans are social animals, and our status in society is much more important than being right. We continuously compare our actions with our contemporaries and alter them to fit in our place.

When we try to debate a person about an issue, our first instinct is to lecture about why our position is correct and accuse them of being wrong, but experiments show that prosecuting typically backfires, and in fact, it strengthens their beliefs. We need to keep communication simple. When trying to change people’s minds, using only data and knowledge may not be the best.

Aristotle identified the three critical elements of communicating thousands of years ago ethos, pathos, and logos. First, credibility, along with emotion and logic, helps people change behavior.

People can persuade someone to change their views by acknowledging the root of the argument and overcoming it before changing their minds. For example, in 1958, only 4% of white Americans endorsed black-white marriages; today, 87% of white Americans do. This highlights that our minds can change for the better.

As Lee McIntyre, in his 2015 book Respecting Truth: Willful Ignorance in the Internet Age, says: “The real enemy of the truth is not ignorance, doubt, or even disbelief,” he writes. “It is false knowledge.”

More from Javaid Iqbal here.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.