As I write this month’s blog, I am thinking of the 94 people who died in Oregon last weekend during Oregon’s abnormal heat wave. Ninety-four people from our community, with the majority in Multnomah county, and 12 in Marion county (where I live). In comparison, In comparison, Oregon has seen 12 people die in the winter months covering the period of 2017-2019. (see https://www.kgw.com/article/news/local/oregon-heat-wave-deaths-grow/283-15223f48-cf99-4b3d-9cce-304e84fc8aa5). According to the KGW news article, many who died had underlying health conditions and did not have an air conditioner or fan available. This is a sobering moment and reminder that we failed to protect our communities. We knew this heat wave was coming, yet we failed to enact procedures that could have reduced the total number of deaths. While not as horrible as the heatwave that killed over 700 people in Chicago in 1995, this means we lost nearly 100 lives (potentially more who are yet to be found and counted).

While the article reports that the majority who died lived in a dwelling that had no air conditioner or fan, it is harder to determine the total number who were homeless/unsheltered or without a home. It is a stark reminder that there is a long way to go – not only to support our community who do not have access to a cooling station, but also to our unsheltered who live and are exposed to the elements every day.

It is estimated that there are nearly 15,000 homeless people living in Oregon (Ellis, 2021). Once the eviction moratorium expires on July 31, 2021, it is expected that thousands more people will become homeless as they will be evicted for non-payment of rent and mortgage payments.

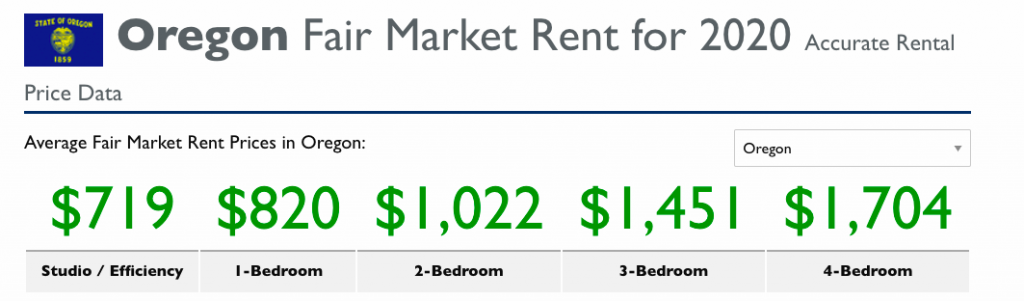

Right now, market rate is at least $800.00 for a one bedroom. For NEW one bedrooms, it may be closer to $900.00. This does not consider whether there are additional recreational uses such as an onsite gym, whether there are laundry hook ups or not, a swimming pool, or basketball court. For a three bedroom, the market rate is $1,450.00/month. This is not acceptable for households where minimum wage (in Oregon) starts at $12.00/hour. The cost of income is not meeting the cost of inflation.

If homelessness a public health crisis, why has more not been done? Why are we continuing to see the rise in homelessness?

Homelessness does not start off with the stereotypically ‘lazy’ or ‘drug addicts’ narrative often thrown around. In fact, homeless could have started as an injury or perhaps an illness that began as a health condition. Overtime, that injury or illness affects employment, which in turn, leading to inability to pay bills, eventually resulting in eviction and being forced out onto the streets (National Healthcare for the Homeless Council, 2019). Overtime, additional health issues result from living on the streets – from addictions that may develop (in the words of a homeless addict I used to work with, “I take drugs not because I want to, but because it helps me stay warm when I am really cold”), to worsening current health conditions, to the development of new health conditions from living on the street (e.g. not being able to maintain a healthy diet, injuries that will not heal, etc).

To address homelessness requires more than providing healthcare and social services. It starts with offering a roof over their head, and not transitional shelters or temporary shelters where at any moment, they may lose it. Some homeless shelters have hard rules – most notably, being a ‘dry’ shelter. It means not having alcohol or doing drugs. Due to the trauma that people have experienced, no alcohol or drugs may not be possible. Then there are others who stayed at shelters, who were attacked, and suffer from the trauma associated with shelters. Others have mental health conditions that prevent them from staying at a home or shelter on their own, because they may attack others, themselves, or scream into the night, disrupting or triggering others who are struggling with mental health trauma as well.

The solution? Stable housing is one way to begin addressing this need; yet the other parts, from social services and intensive programs, must also be ready to go to support the community. A program called, “Housing First” has been implemented in several states, from Utah (see https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-homelessness-housing/once-a-national-model-utah-struggles-with-homelessness-idUSKCN1P41EQ) to Oregon (see https://corvallishousingfirst.org/). However, the success of each program requires continued time, dedication, attention, and most important, money. In the above article, Utah had reduced homelessness by 91%; yet the number of homeless Utahians have now increased in the past 6 years. The Housing First model works; yet with factors that may affect the program, such as not building new housing to accommodate the continued need, lack of attention to healthcare needs of the homeless community, to coordination of services, we will continue to see the homeless population increase.

As a former professor of mine used to say, when public health works, we do not see it. Yet, the moment the system breaks down, all hell breaks loose. We need to do better. We need to focus on our communities to ensure our most vulnerable are taken care of.

More from Jackie Leung here.

Ellis, R. (2021, March 19). Federal analysis shows Oregon’s homeless population in decline prior to pandemic. OPB. https://www.opb.org/article/2021/03/19/federal-analysis-shows-oregons-homeless-population-in-decline-prior-to-pandemic/

National Healthcare for the Homeless Council. (2019, February). Homelessness and Health. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.