McCosker L. Reflections on one of the world’s harshest COVID-19 lockdowns, and on the possibility of eliminating COVID-19 in Australia. HPHR. 2021; 29.

DOI:10.54111/0001/cc5

This cannot be more serious, and it’s not about anything other than being … absolutely straight up: if we don’t make these changes, then we’re not going to get through this.

Daniel Andrews, Premier of Victoria, Australia, announcing the Stage 4 COVID-19 lockdown on August 02, 2020 (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2020b) Tweet

The first case of COVID-19 in Australia was diagnosed on January 25, 2020 (Australian Government Department of Health, 2020), at about the same time as the first case in the US. Within a fortnight, the virus was present in at least three of Australia’s eight major states/territories, and community transmission was occurring (Liebig et al., 2020). By March 18, Australia had recorded a cumulative total of 567 COVID-19 cases and 5 deaths, and the federal government declared the virus to be a biosecurity emergency (COVID-19 Data, 2020; Our World in Data, 2020; Parliament of Australia, 2020a). All of Australia’s state/territory government subsequently implemented lockdowns, asking people to work and study from home, closing non-essential businesses, banning unnecessary travel, and prohibiting mass gatherings (Parliament of Australia, 2020b). Australia also implemented a variety of other responses – for example: vigorously tracing the contacts of known cases, forcibly isolating those contacts, limiting and quarantining international travelers, undertaking extensive testing (including of asymptomatic people), and limiting access to high-risk groups (including those in residential care settings). By the first week of April, we had effectively ‘flattened the curve’ (COVID-19 Data, 2020). Our COVID-19 response was celebrated as “among the most successful in the world” (Duckett & Stobart, 2020).

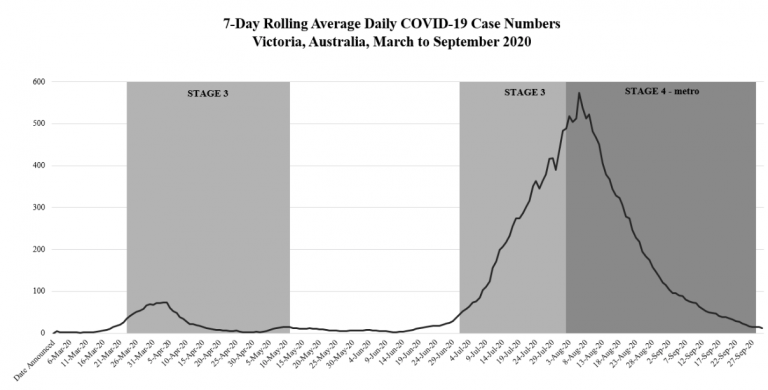

By the end of June 2020, however, Australia’s ‘second wave’ of COVID-19 was beginning (COVID-19 Data, 2020), after the virus escaped from a mismanaged hotel quarantine program in Victoria. There was a resurgence in COVID-19 community transmissions in Victoria and, from early July, a re-implementation of the earlier Stage 3 lockdown in ‘hotspot’ areas (Saul et al., 2020). By mid-July, the Stage 3 lockdown was extended across Victoria, but COVID-19 case numbers – including ‘mystery’ cases, where contact tracers were unable to identify a source – continued to surge (COVID-19 Data, 2020; Saul et al., 2020).

On August 02, 2020, a state of disaster was declared in Victoria, and Stage 4 lockdown was implemented for the approximately 5 million people in the state’s metropolitan areas (Parliament of Victoria, 2020). Stage 4 lockdown involved strategies such as limiting to one the number of people who could leave a residence per day to shop for essential supplies, limiting to one the number of times they could leave, restricting people’s movement to 5 kilometres (3 miles) from their residence, preventing gatherings of >2 people from different residences, applying an 8:00 pm—5:00 am curfew, and making face coverings mandatory in outdoor areas. These strategies were stringently enforced by the police and defense force personnel. Penalties for non-compliance included A$5,000 fines and, for repeat offenders, jail time.

According to Oxford University’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Victoria’s Stage 4 lockdown is among the toughest COVID-19 lockdowns seen to date (Butt, 2020). However, Australia is certainly not the only country to have implemented lockdowns in response to COVID 19; indeed, in the first half of 2020, 85% of US states/territories – in addition to at least 40 other countries globally – issued some type of COVID-19 lockdown (Chaudhry et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020; Moreland et al., 2020). In some cases, these lockdowns were strict. For example: Paris banned daytime outdoor exercise, and Milan prevented people traveling>200 metres from their residence (BBC News, 2020; Ren, 2020). In Santiago, people could leave their residence just twice per week (Al Jazeera News, 2020). In Manila, people aged <21 and >60 were not permitted to leave their residence at all (Mannix, 2020).

The basic aim of lockdown is to reduce human movement and interaction and, thus, to decelerate the spread of COVID-19 (Gollwitzer et al., 2020). This, in turn, prevents the collapse of healthcare systems due to an over-demand of the hospital – and, in particular, intensive care – services (Gollwitzer et al., 2020). Until a COVID-19 vaccine is developed, intermittent, regional lockdowns are likely to be the key public health strategy used to control COVID-19 in most countries. And there is evidence that lockdowns are highly effective – for example: one modeling study found that in the US, three weeks of lockdown resulted in a 48.6% reduction in COVID-19 cases and a 59.8% reduction in fatalities (Fowler et al., 2020). Another modeling study concluded that without lockdowns taking place in the US, COVID-19 case numbers may be 14 times higher (Hsiang et al., 2020). Similar positive results have been obtained from modeling studies applied to other countries significantly impacted by COVID-19 including China (Hsiang et al., 2020), Italy (Hsiang et al., 2020), Spain (Alves dos Santos Siqueira et al., 2020), France (Roques et al., 2020), and Germany (Flaxman et al., 2020). Analysis of historic data from the 1918-19 influenza pandemic – the most recent comparable in scale to the COVID-19 pandemic – shows a strong correlation between lockdowns and delayed peak mortality rates and reduced total mortality (Markel et al., 2007).

Indeed, Victoria’s Stage 4 lockdown was highly effective. Within 1 week of its commencement, COVID-19 case numbers began to fall. Within 6 weeks, 7-day rolling average daily COVID-19 case numbers were consistently <4, down from a peak of 573 (see Figure 1).

However, the major negative socioeconomic impacts of lockdowns must be acknowledged. A study conducted with nearly 14,000 Australians in April/May 2020, during the Stage 3 lockdowns, concluded that anxiety and depression were at least twice as prevalent as before the pandemic (Fisher et al., 2020). Similar results have been seen in studies from the US (Stijelja & Mishara, 2020). After three decades of economic growth, Australia entered a technical recession in March, and >300,000 jobs may be lost in Victoria in 2020 – although modeling suggests that no lockdown may have resulted in an even higher economic toll (City of Melbourne, 2020; Grafton et al., 2020; Reserve Bank of Australia, 2020).

Lockdowns also have a multitude of other impacts. They may cause paradoxical increases in preventable deaths due to avoidance of medical care, increases in substance abuse, domestic violence, and civil unrest, and the magnification of social inequalities (De Filippo et al., 2020; Khubchandani & Price, 2020; Metzler et al., 2020). As most COVID-19 deaths occur in people with limited life expectancy (Metzler et al., 2020), there are difficult questions about the value of saving these lives, and also questions about violations to civil liberty.

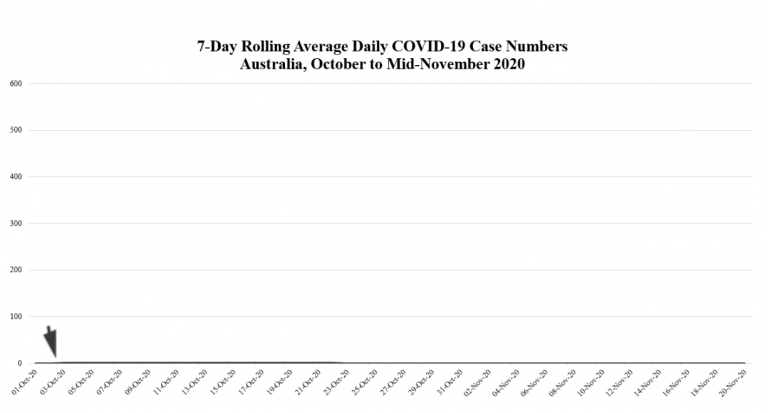

In Australia, however, the benefits of lockdown have far outweighed the detriments. For the past month (at November 23, 2020), our national 7-day rolling average daily COVID-19 case numbers have been <1.0, and for the past week they have been 0.0 (see Figure 2). There are suggestions that Australia might be on the cusp of eliminating COVID-19 entirely (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2020a, 2020c). ‘Elimination’ is not clearly defined in the literature, but it will likely involve a period of absence of COVID-19 infection of at least 28 days, twice the minimum 14-day COVID-19 incubation period (Baker et al., 2020). If Australia were to achieve this, we would join the small number of other nations which have reached ‘COVID-free status’, including our neighbour New Zealand (Lee et al., 2020).

There are a number of reasons why it may be possible to eliminate COVID-19 in Australia – and why elimination may be more complex in other countries, including in the US. Australia is an island nation divided into a small number of states/territories, and we have easily-controllable national and international borders. Our population is small and of a low-density, even in our urban centres. We have a well-funded public healthcare system, with a high rate of testing per capita and efficient communication, contact tracing, quarantine, and self-isolation systems. Our population is generally supportive of, and compliant with, harsh COVID-19 containment measures, as shown by recent landslide elections in Queensland and the Northern Territory. Support is bolstered by generous government financial aid.

But total elimination of COVID-19 is an immense task. In the month it has taken to compile this paper, there have been multiple events in Australia which challenge the likelihood of elimination: a new community outbreak of COVID-19 in South Australia (Government of South Australia, 2020), detection of ‘mystery’ COVID-19 fragments in wastewater in three other states (Victoria State Government, 2020b), and the publication of seroprevalence testing results which suggest COVID-19 rates in Australia may be twice as high as official reports, with extensive asymptomatic transmission (Hicks et al., 2020). It must also be remembered that New Zealand’s apparent ‘COVID-free status’ was broken at the end of August by a surprise COVID-19 cluster, with no known international links (Lee et al., 2020). In striving for elimination, we must avoid complacency which could lead to a ‘third wave’.

The use of lockdowns to control COVID-19 is complex, and elimination is a lofty goal. Lockdowns may not be suitable for all nations, or acceptable to all populations. In Australia, however, lockdowns have been a highly beneficial public health strategy. For many Australians, our social and economic lives are normalizing, albeit to a new ‘COVID-normal’.

Al Jazeera News. (2020). Chile tightens lockdowns as coronavirus cases surpass 200,000. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/6/17/chile-tightens-lockdowns-as-coronavirus-cases-surpass-200000

Alves dos Santos Siqueira, A., Nogueira Leite de Freitas, Y., de Camargo Cancela, M., Carvalho, M., Oliveras-Febregas, A., & Laeandro Bezerra de Souza, D. (2020). The effect of lockdown on the outcomes of COVID-19 in Spain: An ecological study. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236779

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2020a). Coronavirus could disappear in Australia if NSW and Victoria maintain control over next few weeks, experts say. Retrieved November 22, 2020 from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-07/coronavirus-could-be-eliminated-in-australia-epidemiologists-say/12851152

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2020b). State of disaster declared, new restrictions across Melbourne, including 8pm curfew – ABC News. Retrieved November 15, 2020 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkYfnfYwO8o

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2020c). Victoria moves closer to officially eliminating coronavirus after 24 days with no new cases. Retrieved November 23, 2020 from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-23/victoria-records-no-new-coronavirus-cases-and-no-deaths/12909854

Australian Government Department of Health. (2020). First confirmed case of novel coronavirus in Australia. Retrieved 06 July, 2020 from https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/first-confirmed-case-of-novel-coronavirus-in-australia

Baker, M., Kvalsvig, A., & Verrall, A. (2020). New Zealand’s COVID-19 elimination strategy. Medical Journal of Australia. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/new-zealands-covid-19-elimination-strategy

BBC News. (2020). Coronavirus: Paris bans daytime outdoor exercise. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52202700

Butt, C. (2020). COVID-19 government response tracker. Retrieved November 22, 2020 from https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/4093981/?utm_source=showcase&utm_campaign=visualisation/4093981

Chaudhry, R., Dranitsaris, G., Mubashir, T., Bartoszko, J., & Raisi, S. (2020). A country level analysis measuring the impact of government actions, country preparedness and socioeconomic factors on COVID-19 mortality and related health outcomes. EClinical Medicine, 25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100464

City of Melbourne. (2020). Economic impacts of COVID-19 on the City of Melbourne: Final report. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/economic-impacts-covid-19-report.pdf

COVID-19 Data. (2020). Cumulative view of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Australia. Retrieved November 23, 2020 from https://www.covid19data.com.au/states-and-territories

De Filippo, O., D’Ascenzo, F., Angelini, F., Bocchino, P., Conrotto, F., Saglietto, A., Secco, G., Campo, G., Gallone, G., verardi, R., LGaido, L., Iannacone, M., Galvani, M., Ugo, F., Barbero, U., Infantino, V., Olivotti, L., Mennuni, M., Gili, S., Infusino, F., Varcellino, M., Zucchetti, O., Casella, G., Giammaria, M., Boccuzzi, G., Tomomeo, P., Doronzo, B., Senatore, G., Grosso Marra, W., Rognoni, A., Trabattoni, D., Franchin, L., Borin, A., Bruno, F., Galluzzo, A., Gambino, A., Nicolino, A., Giachet, A., Sardella, G., Fedele, F., Monticone, S., Montefusco, A., Omede, P., Pennone, M., Patti, G., Mancone, M., & de Ferrari, G. (2020). Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during COVID-19 outbreak in northern Italy. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(1), 88-89. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2009166

Duckett, S., & Stobart, A. (2020). 4 ways Australia’s coronavirus response was a triumph, and 4 ways it fell short. Retrieved November 22, 2020 from https://theconversation.com/4-ways-australias-coronavirus-response-was-a-triumph-and-4-ways-it-fell-short-139845

Fisher, J., Tran, T., Hammarberg, K., Sastry, J., Nguyen, H., Rowe, H., Popplestone, S., Stocker, R., Stubber, C., & Kirkman, M. (2020). Mental health of people in Australia in the first month of COVID-19 restrictions: A national survey. Medial Journal of Australia. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/mental-health-people-australia-first-month-covid-19-restrictions-national-survey

Flaxman, S., Misra, S., Gandy, A., Unwin, H., Mellan, T., Coupland, H., Whittaker, C., Zhu, H., Berah, T., Eaton, J., Monod, M., Ghani, A., Donnelly, C., Riley, S., Vollmer, M., Ferguson, N., Okell, L., & Bhatt, S. (2020). Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature, 584, 257-261. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7

Fowler, J. H., Hill, S. J., Obradovich, N., & Levin, R. (2020). The effect of stay-at-home orders on COVID-19 cases and fatalities in the United States. MedRXIV. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.13.20063628

Gollwitzer, M., Platzer, C., Zwarg, C., & Goritz, A. (2020). Public acceptance of COVID‐19 lockdown scenarios. International Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12721

Government of South Australia. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Update #25. Retrieved November 22, 2020 from https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/public+health/alerts/health+alerts/coronavirus+disease+%28covid-19%29+update+25

Grafton, Q., Kompas, T., Parslow, J., Glass, K., Banks, E., & Lokuge, K. (2020). Health and economic effects of COVID-19 control in Australia: Modelling and quantifying the payoffs of hard versus soft lockdown. MedRXIV. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.31.20185587

Han, E., Tan, M., Turk, E., Sridhar, D., Leung, G., Shibuya, K., Asgari, N., Oh, J., Garcia-Bastieiro, A., Hanefeld, J., Cook, A., Hsu, L., Teo, Y., Heymann, D., Clark, H., McKee, M., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2020). Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: An analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. The Lancet, 396(10261), 1525-1534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32007-9

Hicks, S., Pohl, K., Neeman, T., McNamara, H., Parsons, K., He, J., Ali, S., Nazir, S., Rowntree, L., T, N., Kedzierska, K., Doolan, D., Vinuesa, C., Cook, M., Coatsworth, N., Myles, P., Kurth, F., Sander, L., Gruen, R., Mann, G., George, A., Gardiner, E., & Cockburn, I. (2020). A dual antigen ELISA allows the assessment of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in a low transmission setting. MedRXIV. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa623

Hsiang, S., Allen, D., Annan-Phan, S., Bell, K., Bolliger, I., Chong, T., Druckenmiller, H., Yue Huang, L., Hultgren, A., Krasovich, E., Lau, P., Lee, J., Rolf, E., Tseng, J., & Wu, T. (2020). The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature, 584, 262-267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8

Khubchandani, J., & Price, J. (2020). Public perspectives on firearm sales in the United States during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12293

Lee, A., Thornley, S., Morris, A., & Sundborn, G. (2020). Should countries aim for elimination in the COVID-19 pandemic? BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3410

Liebig, J., Jurdak, R., El Shoghri, A., & Paini, D. (2020). The current state of COVID-19 in Australia: Importation and spread. MedRXIV. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.25.20043877v1.full.pdf

Mannix, L. (2020). The world’s longest COVID-19 lockdowns: How Victoria compares. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/the-world-s-longest-covid-19-lockdowns-how-victoria-compares-20200907-p55t7q.html

Markel, H., Lipman, H., Navarro, J., Sloan, A., Michalsen, J., Stern, A., & Cetron, M. (2007). Non-pharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298, 644-654. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.6.644

Metzler, B., Siostrzonek, P., Binder, R., Bauer, A., & Reinstadler, S. (2020). Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: The pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32297932/

Moreland, A., Herlihy, C., Tynan, M. A., Sunshine, G., McCord, R. F., Hilton, C., Poovey, J., Werner, A. K., Jones, C. D., Fulmer, E. B., Gundlapalli, A. V., Strosnider, H., Potvien, A., Garcia, M. C., Honeycutt, S., & Baldwin, G. (2020). Timing of state and territorial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and changes in population movement – United States, March 1-May 31, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(35), 1198-1203. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935a2.htm

Our World in Data. (2020). Australia: What is the cumulative number of confirmed deaths? Retrieved November 23, 2020 from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/australia?country=~AUS

Parliament of Australia. (2020a). COVID-19 legislative response – Human biosecurity emergency declaration explainer. Retrieved 06 July, 2020 from https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2020/March/COVID-19_Biosecurity_Emergency_Declaration

Parliament of Australia. (2020b). COVID-19: A chronology of state and territory government announcements (up until 30 June 2020). Retrieved November 23, 2020 from https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2021/Chronologies/COVID-19StateTerritoryGovernmentAnnouncements

Parliament of Victoria. (2020). Emergency powers, public health and COVID-19. Retrieved November 22, 2020 from https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/publications/research-papers/download/36-research-papers/13962-emergency-powers-public-health-and-covid-19

Ren, X. (2020). Pandemic and lockdown: A territorial approach to COVID-19 in China, Italy and the United States. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15387216.2020.1762103

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is causing significant strains in the global financial system. Retrieved November 23, 2020 from https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/fsr/2020/apr/overview.html

Roques, L., Klein, E., Papaix, J., Sa, A., & Soubeyrand, S. (2020). Impact of lockdown on the epidemic dynamics of COVID-19 in France. Frontiers in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00274

Saul, A., Scott, N., Crabb, B., Majundar, S., Coghlan, B., & Hellard, M. (2020). Victoria’s response to a resurgence of COVID-19 has averted 9,000-37,000 cases in July 2020. Medical Journal of Australia. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/victorias-response-resurgence-covid-19-has-averted-9000-37000-cases-july-2020

Stijelja, S., & Mishara, B. (2020). COVID-19 and psychological distress – Changes in internet searches for mental health issues in New York during the pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Association. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3271

Victoria State Government. (2020a). Victorian coronavirus (COVID-19) data. Retrieved November 15, 2020 from https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorian-coronavirus-covid-19-data

Victoria State Government. (2020b). Wastewater monitoring – Coronavirus (COVID-19). Retrieved November 22, 2020 from https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/wastewater-monitoring-covid-19

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.