Griner S, Farris A, Johnsohn K, Akpan I, Alkhatib S, Chirayil A, Dewitt H, Neelamegam M. Confidence in sexual health communication by gender identity and sexual orientation among college students. HPHR. 2024;82. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/DDDD7

College-aged individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors associated with negative health outcomes, such as inconsistent condom use and having multiple concurrent sexual partners. Communication about sexual health topics with partners has been shown to predict safer sex practices in heterosexual students, yet few studies have examined sexual health communication skills by other demographic factors. This study examined differences in sexual health communication confidence among college students by gender identity and sexual orientation.

Data were collected via an online survey at a large southeastern university (n=812). Items assessing confidence in communicating with sexual partners regarding seven topics, including condom use, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and unplanned pregnancies, were analyzed. Kruskal-Wallis tests and post-hoc Mann-Whitney tests with Bonferroni adjustment were conducted.

Significant differences in confidence were found across gender identity and talking about what they want during sex (p=0.031) and STIs (p=0.007) and across sexual orientation and talking about sex with partners (p=0.002), saying no to sex (p=0.010), and talking about what they want during sex (p=0.031).

Higher education institutions should emphasize communication skills when providing sexual health information and education to students, specifically regarding STI screening and prevention, consent communication, and discussions about sexual pleasure with partners. Furthermore, sexual health information should be tailored based on gender identity and sexual orientation to improve communication confidence between partners.

These results suggest that there are specific areas of communication to be addressed in sexual health programming on college campuses. Future studies should examine the qualitative differences in communication and the specific barriers and facilitators to each topic.

To explore sexual health communication confidence among college students, data were collected via convenience sampling through the student organization portal of a large southeastern university. Inclusion criteria to participate in this study were: (1) current enrollment in the specified college and (2) over the age of 18 years old. The survey was distributed to a total of 803 student organizations via the portal. During administration, 1,212 students began the survey, and 1,195 students completed the survey. However, 80 observations were not included due to missing responses for gender identity, 21 observations were missing other demographic variables, and 282 missing communication confidence questions; thus, the final analytic sample size was 812 students.

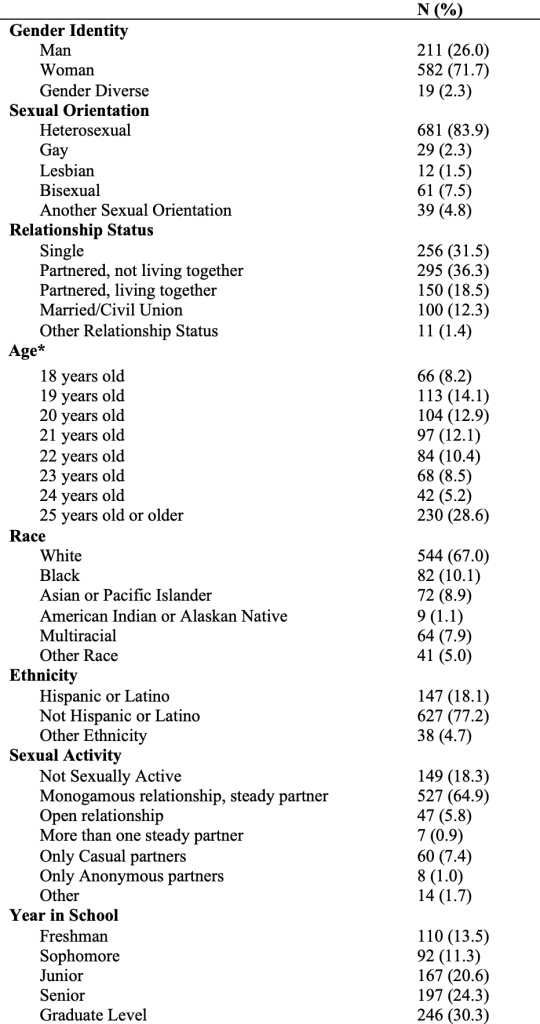

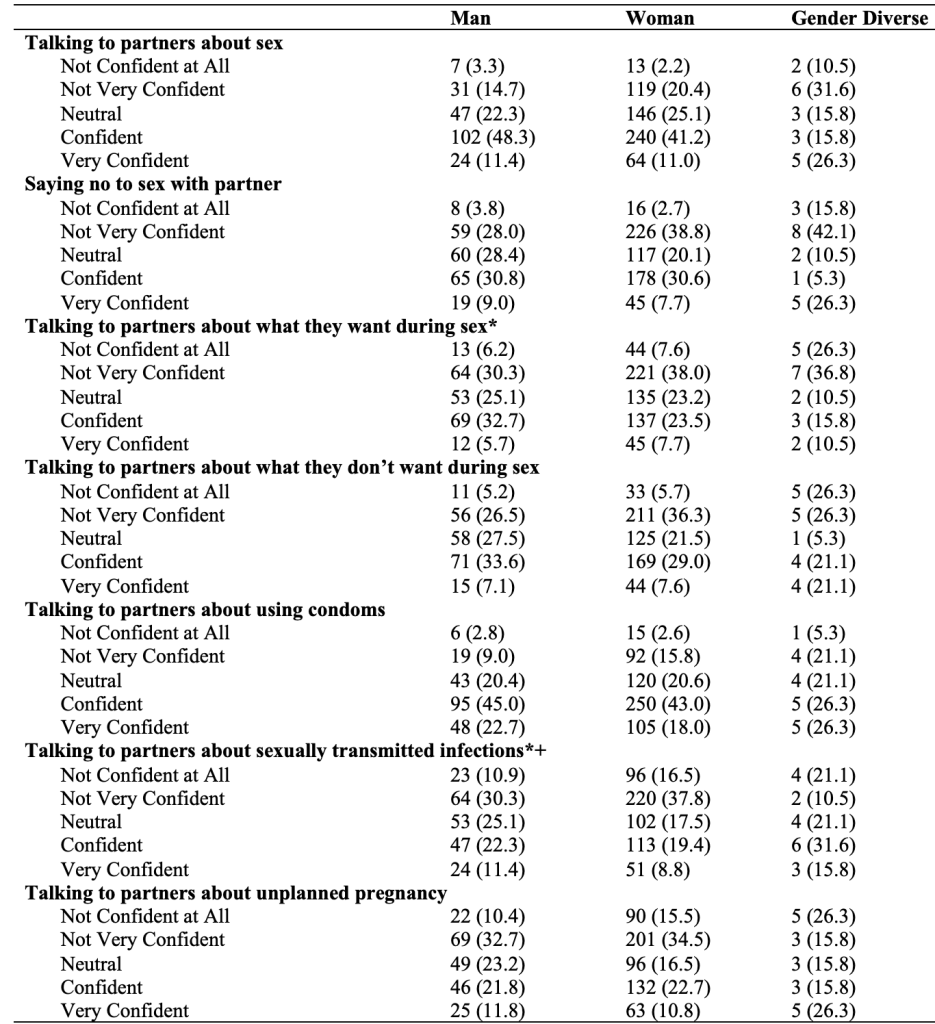

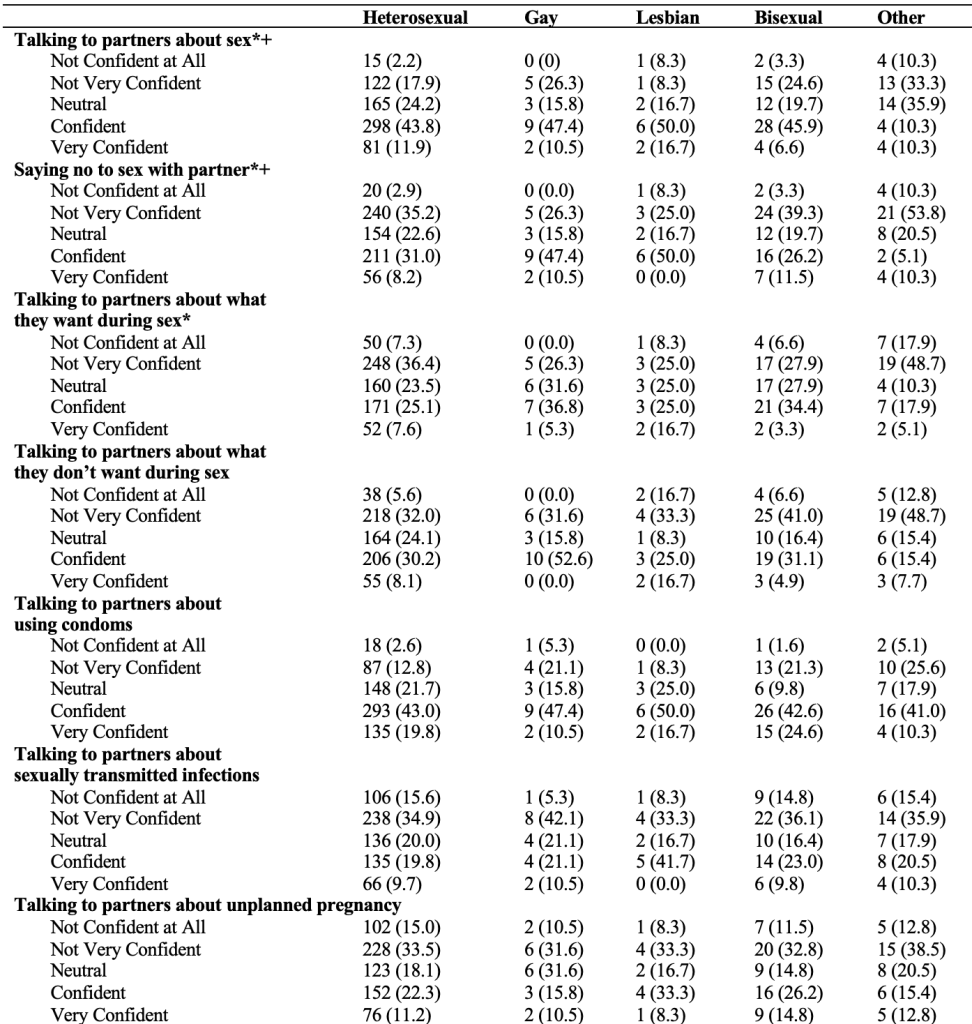

Demographics measured included gender identity, sexual orientation, relationship status, sexual activity, age, race, ethnicity, and year in school. Gender identity was measured with an item asking, “How do you identify your gender?” Response options were man, woman, transgender (assigned male at birth), transgender (assigned female at birth), and another identity with a write-in option. However, due to a small number of students identifying as transgender, the last three categories were combined into a gender-diverse category. For the item measuring sexual orientation, participants were given response options of straight/heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, or another identity with a write-in option. Relationship status included response options of single, partnered but not living together, partnered and living together, married or civil union, and other. Sexual activity was measured by asking, “Who are you currently sexually active with? This means vaginal, anal, oral sex, or mutual masturbation. Check all that apply.” Response options included: Not sexually active, steady partner (monogamous relationship), steady partner (open relationship), more than one steady partner, only casual partners, only anonymous partners, and something else with a write-in option. Year in school ranged from freshman to graduate level. Race was measured by response options of Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, white, multiracial, or another identity; ethnicity included response options of Hispanic/Latino, not Hispanic/Latino, and other.

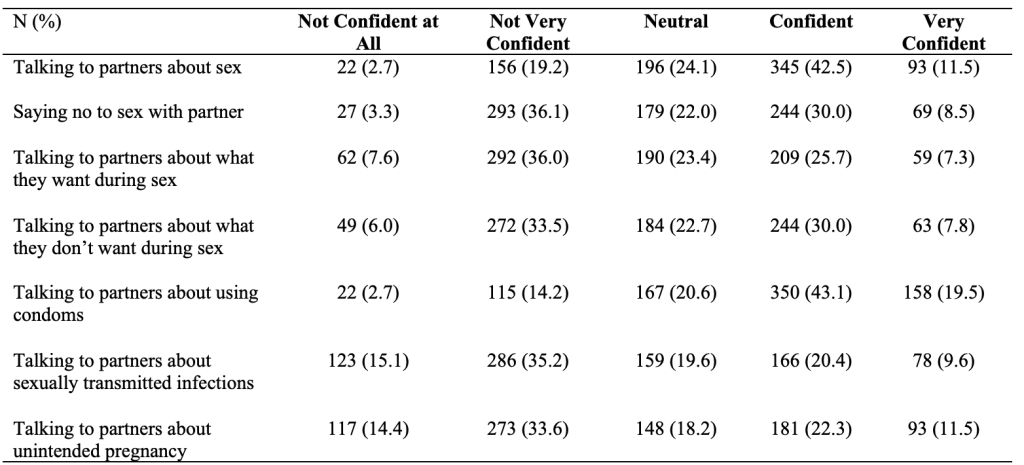

Items assessing communication confidence with sexual partners regarding seven topics were analyzed. Item stem was “How confident do you think college students feel about: Talking to their sexual partners about sex?; Saying no to sex with their partner?; Talking to their partners about what they want during sex?; Talking to their partners about what they don’t want during sex?; Talking to their partners about using condoms?; Talking to their partners about sexually transmitted infections?; Talking to their partners about unplanned pregnancy?” Response options for these items were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from not at all confident to very confident.

Frequencies were conducted for all demographic variables. Bivariate statistics were used to describe the association between communication confidence and gender identity, sexual orientation, and relationship status, respectively. Due to the small number of responses by some groups, Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to determine independence of demographics and communication confidence. Post-hoc Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the groups, controlling for Type I error across tests by using the Bonferroni approach. Adjusted p values for each analysis indicating significance are reported. All analyses were performed in SPSS.

Overall, the majority of study participants (n=812) identified as women (72%), heterosexual (84%), partnered and not living together (36%), were in a monogamous relationship (65%), white (67%), and enrolled in a graduate program (30%). Over 28% of students were aged 25 or older.

The majority of students in this sample reported feeling Not Very Confident, Neutral, or Confident about sexual health communication with their partner. Most students felt Confident in taking to their partners about sex (43%) and about condom use (43%). Students felt Not Very Confident in talking to their partners about saying no to sex (36%), what they want during sex (36%), what they do not want during sex (34%), STIs (35%), and unintended pregnancies (34%).

Kruskal Wallis tests showed differences in communication confidence by gender identity with talking to partners about what they want during sex (Kruskal Wallis [KW], X2 = 6.94, df = 2, p = 0.031) and talking to partners about STIs (KW, X2 = 9.93, df = 2, p = 0.007). The results of the post-hoc Mann-Whitney tests with Bonferroni Adjustment (adjusted p value <0.017) found that men (p = 0.004) reported significantly higher confidence in talking to partners about STIs than women. However, no significant differences were found in communication confidence between men and gender diverse people (p = 0.041) or women and gender diverse people (p = 0.497). The five remaining topics of communication were not significantly different by gender identity.

Significant differences in confidence were found in the topics of talking about sex with partners (KW, X2 = 17.56, df = 4, p = 0.002), saying no to sex with partners (KW, X2 = 13.17, df = 4, p = 0.010), and telling partners what they want during sex (KW, X2 = 10.64, df = 4, p = 0.031). Ten post-hoc Mann-Whitney tests with Bonferroni Adjustment (adjusted p value <0.005) were conducted and found that students who identified as straight/heterosexual were more confident in talking to partners about sex (p < 0.000) and saying no to sex with partners (p = 0.001) than those in the “another identity” sexual orientation group. Additionally, the students who identified as gay (p = 0.003) were more confident in saying no to sex with partners than students in the “another identity” category. However, telling partners what they want during sex was not significantly different between groups, and no other significant pairwise comparisons were found among sexual orientation.

In summary, this study found that gender identity and sexual orientation impact sexual health communication confidence among college students. Higher education institutions are prime targets for intervention and are essential in providing resources related to sexual health communication to improve sexual health equity among this population. When providing sexual health information and education to students, colleges should emphasize communication information and skills, specifically regarding sex and condom negotiation, STI screening and prevention, and sexual desires. Moreover, to improve health communication, sexual health information should be tailored based on gender identity and sexual orientation to improve communication confidence and skills among all college students, including those who do not identify within a binary gender category.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest

Dr. Stacey Griner is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Alexandra Farris is a Project Coordinator in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Kaeli Johnson is a PhD student and graduate research assistant in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Idara Akpan is a PhD candidate and graduate research assistant in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Sarah Alkhatib is a PhD student and graduate research assistant in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Ann Chirayil is an OMS-II student in the Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Holly Dewitt is an OMS-II student in the Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Dr. Malinee Neelamegam is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.