Liu A, Pinkney J, Ruiz F. Bridging the gap: culturally competent care in Alzhiemer’s disease and relate Dementias. HPHR. 2024. 82. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/DDDD2

In the United States, Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minorities. Underlying drivers for the disparities in ADRD burden include limited access to healthcare, barriers to research engagement, and cultural competency gaps. Addressing these disparities is crucial for both ethical and financial reasons, necessitating collaboration among stakeholders like the Alzheimer’s Association, the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Association of Community Health Centers. This paper outlines three policy solutions to address disparities in ADRD: 1) designating at least one mobile health unit for the provision of ADRD-related care in minority communities in each state; 2) increasing diversity in clinical trials; and 3) creating culturally sensitive ADRD diagnostic and awareness tools and materials. These strategies aim to bridge healthcare system gaps, ensuring accessible and community-tailored resources for ADRD.

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) are a group of progressive neurological conditions characterized by a decline in cognitive abilities.1 Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent form of dementia, results from the accumulation of abnormal proteins in the brain, leading to memory loss, impaired thinking, and difficulty in performing everyday tasks.1 Dementias, a broader category, encompass various disorders like vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia, each with its unique underlying causes and symptoms. These conditions share the common feature of cognitive decline, affecting memory, language, reasoning, and overall functioning, often challenging individuals and their families.1 ADRD disproportionately affects marginalized communities, making it a critical social justice and equity issue.

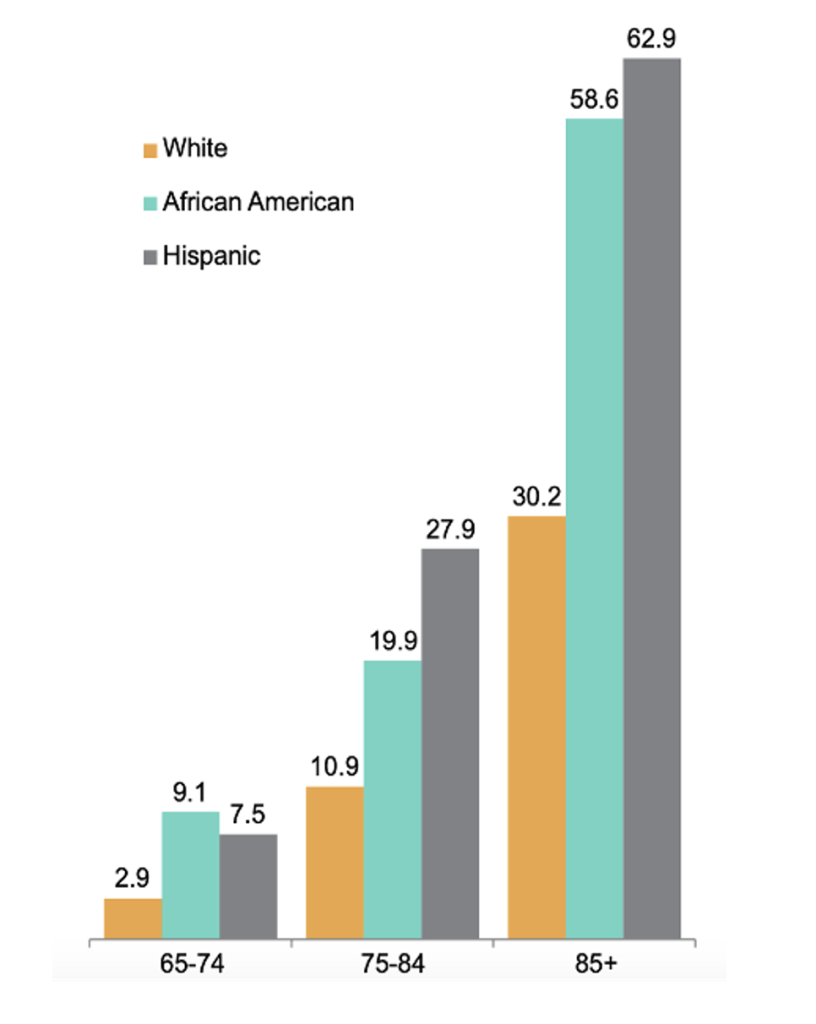

While the majority of the over 5 million people in the U.S. with Alzheimer’s disease are of white ethnicity, studies indicate that minority populations face a significantly higher risk of developing ADRD.1 For example, African American/Black populations are approximately twice as likely as whites to be affected by these cognitive conditions, while Hispanics are about one and a half times more likely than their white counterparts to experience ADRD (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of People Age 65+ with Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias. Source: Reference 1.

Several theoretical frameworks elucidate the relationship between minority status and cognitive reserve deficits over time. Nancy Krieger’s ecosocial theory introduces the construct of embodiment, which emphasizes that differences in disease patterns across populations often serves as a embodied reflection of their “stories” or lived experiences—such as socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, and exposure to discrimination— that they “may be unable, forbidden, or choose not to tell.”.2 Minority individuals often face socioeconomic disadvantages and racism, which can negatively affect cognitive reserve—the brain’s ability to withstand neuropathological damage—over time.3 Encounters with both subtle and overt racial discrimination are linked to depression, anxiety, and decreased sleep quality, all factors connected to cognitive decline.4

David Williams has extensively researched the link between perceived racism and cognitive, mental, and physical health outcomes.5,6,7,8 His work highlights how these stress responses can lead to allostatic load, the cumulative wear and tear on the body from chronic stress, resulting in poorer health over time. Building on this, Ilan Meyer’s minority stress model examines the chronic stress experienced by LGBT individuals, positing that discrimination and social exclusion contribute to higher allostatic load. This increased load is associated with adverse health outcomes, including cognitive decline.9 Transgender and nonbinary older adults with subjective cognitive decline were more likely to report facing discrimination in medical environments.10 Those who experienced such discrimination were 4.5 times more likely to experience memory deterioration and 7.5 times more likely to have poor or fair memory.11

Despite minority populations having a higher incidence of ADRD compared to whites, they are less likely to receive a formal diagnosis for these conditions. For example, African Americans are only 34% more likely to have an official diagnosis. Similarly, Hispanics have an 18% higher likelihood of receiving a diagnosis.1 The lower likelihood of diagnosis among racial and ethnic minorities for ADRD stems from a lack of access to healthcare services. Systemic barriers such as socioeconomic disparities, geographic limitations, and inadequate insurance coverage hinder these communities’ ability to seek and receive timely medical attention.16 Additionally, cultural stigmas surrounding mental health and cognitive decline persist in many minority communities, which can lead to underreporting of symptoms and reluctance to pursue diagnosis and treatment.17 These stigmas often arise from a combination of fear, misinformation, and cultural beliefs about aging and mental health, further compounding the challenges faced in effectively diagnosing and managing ADRD in these populations.1

This underdiagnosis is problematic in communities with early and aggressive onset of ADRD because it delays critical interventions and access to resources that can help manage the disease.12 Minority patients tend to receive their diagnoses during the later stages of the disease when they experience more significant cognitive and physical impairments, necessitating a higher level of medical care. Delays in diagnosing dementia significantly impact the long-term survival and quality of life of minority patients.11 These patients often face more severe symptoms and complications due to the late stage at which their condition is identified. The delay in diagnosis can lead to faster cognitive decline, greater functional impairment, and reduced overall well-being.12

Additionally, minority patients frequently present with comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.13 These comorbidities exacerbate the progression of dementia and complicate its management. For instance, a study found that individuals with dementia and comorbidities tend to experience higher rates of hospitalization and longer hospital stays, which further diminishes their quality of life and increases caregiver burden.14 Furthermore, the interaction between dementia and these chronic conditions often leads to increased healthcare costs and more complex treatment regimens, which can contribute to poorer outcomes.14

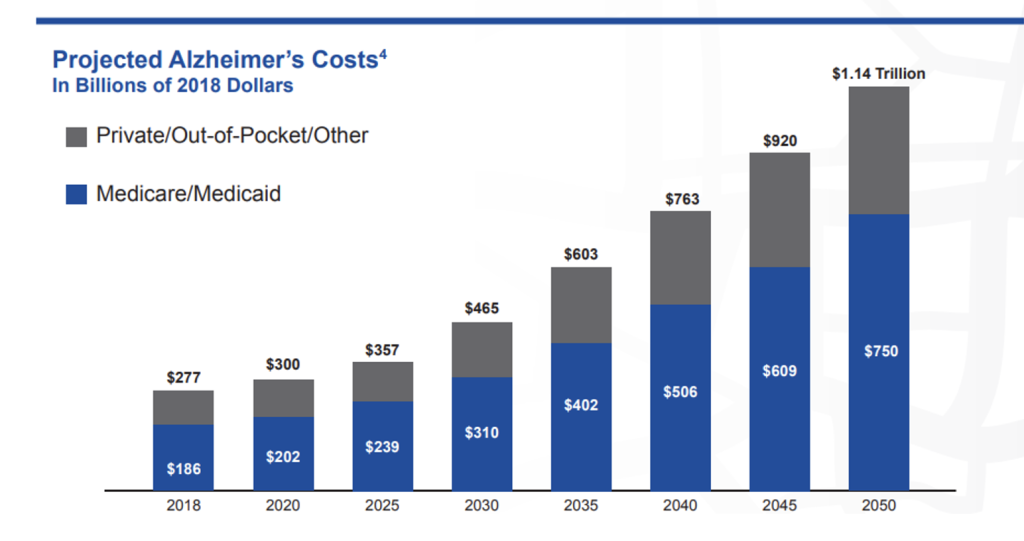

Consequently, minority patients require significantly more hospital, physician, and home health services, leading to substantially higher healthcare costs compared to their white counterparts with the same condition. The rising cost of ADRD care, projected to reach $1.14 trillion by 2050 (Figure 2), is significantly driven by such disparities. The estimated annual medical care and caregiving costs associated with dementia among Hispanic and Black individuals are $20,000 higher than for their White counterparts.15 Cognitive health disparities in minority communities result in substantial opportunity costs, such as early retirement, lost income, and increased caregiver burden, leading to broader economic disparities. Beyond individual and familial impact, these disparities strain the healthcare system and society.

Figure 2: Projected Cost of Alzheimer’s Care. Source: Reference 15.

These statistics highlight several critical needs in the field of ADRD:

First, there is a need for improved healthcare access to ensure that individuals in minority communities receive the appropriate support and care for cognitive health issues. Social inequities, rooted in historical injustices and structural racism, create barriers to healthcare access for minority communities. For example, Black and Hispanic populations often face economic disadvantages, limited healthcare resources, and lack of health insurance, which hinder timely medical consultations and screenings for cognitive issues.18 Early diagnosis and timely interventions are crucial for managing ADRD. Moreover, early detection and intervention mitigates the burden on the U.S. healthcare system.18

Second, medical research plays a role in addressing disparities related to cognitive health. Clinical trials and research studies have been disproportionately conducted on non-minority populations, which does not fully represent the diverse range of individuals affected by cognitive conditions.19 Research institutions often prioritize funding for populations where higher rates of ADRD are observed, which leads to disproportionate focus on white populations.19 Furthermore, a historical legacy of medical abuses, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, has fostered deep-seated mistrust in medical institutions among Black and brown communities.20 This mistrust is compounded by the underrepresentation of people of color in the clinical workforce, making it less likely for minority patients to find culturally aligned care providers with whom they feel comfortable and understood.20 Nearly two-thirds of Black Americans (62%) believe that medical research is biased against people of color — a view shared by substantial numbers of Asian Americans (45%), Native Americans (40%) and Hispanic Americans (36%).21 A more inclusive approach to medical research is needed to understand how cognitive health conditions manifest across different racial and ethnic groups, as well as to develop treatments and interventions that are effective for everyone.

Third, there is a need for better understanding of minority populations’ ethnic, racial, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds and experiences. Fewer than half of Black (48%) and Native Americans (47%) feel confident they have access to providers who understand their ethnic or racial background, and only about 3 in 5 Asian Americans (63%) and Hispanics (59%) likewise feel confident.1 Language differences can create communication challenges between healthcare providers and minority patients. This can hinder the exchange of critical information and make it harder for patients to access care and support. Most of the testing done to diagnose dementia is very subjective and not particularly reliable with lots of sources of variance, making it even more difficult to assess in patients with significant language barriers.

Addressing this issue requires collaboration across various stakeholders, encompassing healthcare professionals, organizations, and policymakers. Key players include the Alzheimer’s Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). The Alzheimer’s Association is a leading authority on ADRD, providing critical support services and advocacy efforts.1 The CDC’s role in data collection and public health initiatives makes it instrumental in addressing disparities.22 Meanwhile, the NACHC represents community health centers that serve as vital healthcare access points for underserved populations, positioning them as essential partners in delivering culturally competent ADRD care.23

The Alzheimer’s Association and CDC led the Healthy Brain Initiative’s (HBI) State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia Road Map, which outlines 4 key pillars: (1) Strengthen partnerships and policies; (2) Measure, evaluate and utilize data; (3) Build a diverse and skilled workforce; and (4) Engage and educate the public. Equity is highlighted as an objective for each of the 4 pillars.24 This initiative has been accelerated by passage of the Building Our Largest Dementia Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act (BOLD Act) (Public Law 155-406) in 2018.25 This act has been allocated $50 million dollars per year according to the Congressional Budget Office. Section 2 (B) (vi) of the act stipulates that grant funding be allocated to projects that reduce disparities related to the care and support of individuals with ADRD. This existing funding can be leveraged. Alongside these essential organizations, it is also imperative to engage directly with patients, geriatricians, community health workers, and local communities. HBI incorporates plans for partnerships across the community, including faith communities, small businesses, and civic and social justice organizations.24 This holistic approach integrates the expertise of healthcare professionals and the lived experiences of patients and communities. This collaboration is crucial for developing and implementing culturally congruent resources and comprehensive care strategies that bridge the gap between diverse communities and healthcare systems.24

Three key policy recommendations are outlined with the aim of reducing disparities in dementia care within minority communities. The proposals include (1) the deployment of mobile health units in underserved minority communities across the country, (2) initiatives to increase minority participation in clinical trials, and (3) the development of culturally congruent ADRD awareness campaigns and diagnostic tools.

Section 2 (B) (c) of the 2018 BOLD Act amended Section 398 (A) of the Public Health Service Act to stipulate “improved coordination for activities and programs related to dementia …that do not unnecessarily duplicate activities and programs of other agencies and offices within the Department of Health and Human Services.”.24 In addition, Section P-2 of HBI calls for state and local health departments to utilize community-clinical linkages to improve equitable access to community-based chronic disease prevention, dementia support, and healthy aging programs.24 The goals of these policies can be combined with the goals of the Mobile Health Care Act and NACHC to ensure increased access to dementia screening and care using mobile health center units. Specifically, a policy that consolidates these multi-sector efforts should be used to establish regulations at the state and local level. Public health departments should stipulate that at least one such mobile unit in each state provides annual screening, prevention, and treatment services for individuals at high risk of ADRD in predominantly minority communities.24

Pharmaceutical companies and research institutions should include diverse populations in clinical trials, focusing on achieving participant proportions that mirror the disease burden. The implementation plan encompasses legislative changes that make diversity in clinical trials a mandatory requirement, bolstered by incentives to encourage compliance. Furthermore, the policy involves the launch of nationwide awareness campaigns designed to educate both the public and researchers on the significance of diversified clinical trial participation. This strategy also calls for the engagement of study investigators from underrepresented populations in leadership roles within the research teams, enhancing the design and execution of diversified clinical trials. While specific examples of clinical trials with study investigators from underrepresented populations in leadership roles have not been documented, efforts to promote diversity in research leadership are gaining recognition within the scientific community. The FDA’s Diversity in Clinical Trials Initiative encourages pharmaceutical companies, research institutions, and clinical trial sponsors to prioritize diversity in all aspects of clinical research, including leadership roles.26

The development of culturally and linguistically congruent diagnostic tools and awareness campaigns aims to close the gap in ADRD care by tailoring services to meet the specific needs of minority communities across the country. For the implementation of this policy recommendation, the agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should provide coordination and support. The policy involves updating the National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards to include transcreation, which ensures that materials reflect the nuances of language and culture.27 The National CLAS Standards, established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, comprise 15 guidelines organized into three themes: culturally competent care, language access services, and organizational supports for cultural competence.27 These standards aim to ensure that healthcare organizations and providers deliver respectful, understandable, and effective care to individuals from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. They emphasize the importance of healthcare providers understanding and respecting the cultural beliefs and practices of their patients, providing language assistance services for individuals with limited English proficiency, and integrating cultural competence and language access into organizational governance and quality improvement activities.27

Transcreation of current cognitive screening tools for dementia involves adapting these assessments to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness while maintaining their validity. This process includes modifying questions, tasks, and language to reflect the cultural beliefs and linguistic preferences of diverse populations. Linguistic validation, cognitive equivalence testing, and cultural sensitivity considerations are essential to ensure that the transcreated tools accurately measure cognitive function across different language and cultural groups.

The culturally and linguistically congruent diagnostic tools and awareness campaigns developed under this policy recommendation will be made available through various channels to ensure broad access. They will be disseminated through healthcare organizations, community health centers, public health departments, and online platforms managed by the Department of HHS. These resources will be targeted towards healthcare providers, empowering them with the knowledge and tools to deliver culturally competent care and conduct dementia screenings tailored to the needs of minority communities. Additionally, materials will also be designed for patients and their families to use independently or in collaboration with their healthcare providers, providing educational resources and guidance on navigating the healthcare system.

Community engagement is a pivotal cornerstone within this policy, and community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) plays a crucial role in informing the development, implementation, and evaluation of interventions.28 Community stakeholders, such as individuals affected by ADRD, caregivers, community leaders, healthcare providers, and representatives from civic and social organizations, contribute valuable insights and expertise to ensure that policies are culturally responsive, relevant, and effective. For instance, CBPAR helps identify the unique cultural beliefs, values, and preferences of minoritized communities regarding brain health and aging. Additionally, stakeholders provide input on the cultural and linguistic congruency of materials, including format, content, and language. Moreover, CBPAR facilitates the identification of barriers and facilitators to participation in support groups and other interventions, enabling tailored strategies to overcome obstacles and enhance engagement. This process, which includes cultural sensitivity assessments, cognitive testing, and feedback from focus groups or community consultations, ensures that materials resonate with the target audience. By fostering connections that bridge disparities in dementia care through community engagement, the policy sets a path toward a healthcare system that meets the unique needs of minority communities.

The three proposals outlined have significant implications for addressing disparities in ADRD care within minority communities, particularly when viewed through the lens of theoretical frameworks such as Nancy Krieger’s ecosocial theory. These frameworks help elucidate the relationship between minority status and health disparities, providing a comprehensive understanding of how social determinants of health and chronic stress contribute to cognitive decline.

First, deploying mobile health units in underserved minority communities addresses a critical need for increased access to dementia screening and care. Krieger’s ecosocial theory emphasizes how the embodiment of social inequalities—such as limited access to healthcare—impacts health outcomes. By bringing healthcare services directly to communities with significant barriers to access, mobile health units can increase healthcare access and improve health outcomes in underserved populations.

Second, initiatives to increase minority participation in clinical trials represent a critical step towards ensuring that medical research reflects the diversity of individuals affected by cognitive health conditions. By promoting diversity in clinical trials and engaging study investigators from underrepresented populations, the policy aims to enhance the relevance and effectiveness of research findings for minority communities.

Last, developing culturally and linguistically congruent diagnostic tools and awareness campaigns addresses the need for healthcare services that are effective for individuals from diverse backgrounds. Krieger’s theory underscores the role of lived experiences, including cultural and linguistic factors, in shaping health outcomes. By updating the National CLAS standards to include transcreation of materials, this policy ensures that diagnostic tools and awareness campaigns are tailored to the cultural and linguistic needs of minority communities. This approach not only fosters trust but also empowers individuals to engage in their healthcare, as supported by studies demonstrating the effectiveness of culturally appropriate care in improving health outcomes.29

Incorporating theoretical frameworks into the proposed policies provides a robust foundation for addressing the multifaceted nature of health disparities in ADRD care. By acknowledging and targeting the social determinants of health and chronic stressors specific to minority populations, these approaches hold significant promise for mitigating the impact of minority stress on cognitive health.

Altogether, the three policies aim to bridge the gap between minority communities and the healthcare system, ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their racial or ethnic background, have access to appropriate, culturally sensitive resources and support for ADRD. One strength of the proposals lies in their comprehensive approach, which encompasses both preventive measures and targeted interventions to address disparities at multiple levels. By targeting access to care, representation in research, and the cultural responsiveness of healthcare services, these proposals address key barriers to equitable ADRD care within minority communities. Additionally, the emphasis on community engagement and stakeholder involvement enhances the relevance and acceptability of these initiatives, fostering trust and empowering individuals to take an active role in their healthcare decisions.

However, several challenges should be acknowledged. First, the implementation of these proposals may face logistical and resource constraints, particularly in areas with limited healthcare infrastructure and funding. The success of mobile health units, for example, relies on sustained investment and coordination among multiple stakeholders, which may be challenging to achieve. Second, efforts to increase minority participation in clinical trials face historical mistrust and structural barriers within research settings, requiring comprehensive strategies to build trust and address systemic inequities. Furthermore, while developing culturally and linguistically congruent diagnostic tools and awareness campaigns is crucial, ensuring their accuracy and effectiveness demands ongoing commitment to cultural competence training among healthcare providers and robust quality assurance mechanisms.

Despite these challenges, the proposals offer valuable opportunities for advancing equity in ADRD care and promoting the well-being of minority communities. By addressing systemic barriers, promoting diversity in research, and fostering cultural responsiveness in healthcare delivery, these initiatives have the potential to reduce disparities and improve outcomes for individuals affected by ADRD across diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds.

Alice Liu is a medical student at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth in Hanover, NH.

Jodian Pinkney is an infectious disease physician at the Mass General Brigham in Boston, MA.

Francisco Ruiz serves as the Director of the White House Office of National AIDS Policy. He is a doctoral of public health candidate at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston, MA.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.