Wright R. Analyzing water conditions and educating community healtth workers in a rural community in the Dominican Republic. HPHR. 2024. 84. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/FFFF1

El Chacuey is a small rural community in the Dominican Republic. Drought is a common occurrence in this area and many families struggle to access water from the nearby river, resulting in several cases of water-related diseases and loss of opportunities to pursue socioeconomic activities. In 2018, El Chacuey expressed interest in planning the implementation of a new water supply system that emphasized water quality and quantity.

Household surveys were created to determine El Chacuey’s unmet water needs, current water usage, and plans to maintain a future water system. Local water committee members were trained on project and financial management, as well as educated community health workers on Aedes aegypti mosquito control methods in the local clinic.

A total of 73 household surveys were administered in a two-week timespan. Among respondents, 22% reporting receiving adequate water regularly from the current gravity-fed water system. All participants stated that the water supply is unreliable and that a better water system needs to be implemented. Additionally, the water committee meeting and the Zika virus educational training were successfully implemented.

A new water system would greatly benefit the community. To pursue a sustainable rural water infrastructure, it is important to coordinate actions between all stakeholders. This includes the water committee, which will be responsible for the long-term maintenance of the water system. Addressing the community’s water-related needs can guide decision-making processes related to water infrastructure development and can ensure that water resources are managed sustainably and equitably. Moreover, community health workers’ knowledge of Zika virus transmission can play a crucial role in implementing preventive measures within the community, empowering families to take appropriate preventive actions.

A new water supply system should be built in El Chacuey.

Clean water is vital for health, food production, and economic development yet over two billion people worldwide lack access to safe water.1 This is known as water insecurity – the inability to access adequate, reliable, and safe water for a healthy life.2 The World Health Organization and UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene has documented improvements to clean water access in rural areas within the Dominican Republic where 16% of the population inhabit, stating that 97.1% of the rural communities have seen an improvement in water quality in 2019, up from 85.9% in 2014.3-4 Baum et al. (2014) however, contends that the perceived improvement in water quality may be overstated due to the absence of microbial quality assessments in current water quality evaluations.5 Nonetheless, improvements have been made and may be partially due to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that have helped rural communities improve existing water supply infrastructure. Though improvements may have been made to access water, many rural communities still face water shortages and insufficient access to clean water. Studies have shown that a lack of clean water is associated with several negative health outcomes, including diarrheal disease, dehydration, and poor perceived health.6-10 It therefore remains imperative to improve water supply infrastructure to improve overall public health within these communities.

El Chacuey is a small rural community of around 400 individuals located in the province of Dajabon in the northwest of the Dominican Republic. Drought is a common occurrence in this area, especially during the dry season. International NGOs have attempted to mitigate the impact of drought in this region. For example, in 1999, Prolino, a European nonprofit organization, built a water distribution system in El Chacuey on the outskirts of the community that consisted of a 30,000-gallon storage tank connected to the Rio de Chacuey. Although the NGO had the good intention of providing access to clean water, to my knowledge, the NGO did not consult the community in building the water system nor was there any associated trainings or funding to maintain the water system. The lack of communication and engagement between the NGO and the community shows the element of paternalistic behavior, causing a power imbalance between the two parties. Nearly 20 years later, in January 2018, REDDOM, a non-governmental organization that deals with rural economic development, examined the water system and determined that the outdated gravity-fed water system was unable to supply water to all households in El Chacuey. The difficulty in accessing water from the Rio de Chacuey over the past decade has resulted in several cases of water-related diseases and loss of opportunities to pursue socioeconomic activities.

In 2018, El Chacuey expressed interest in installing an updated water supply system that could provide clean, safe water. The delay in a water system building project reflected the community leaders’ struggle to find the necessary financial and technical resources to build such a system. A water committee was formed as a strategic approach to engage community leaders and other stakeholders, to identify needs and priorities, collaborate with technical experts, and access funding. The water committee consisted of 13 members, 38% of whom were women. All members were responsible for the management of the water system once built.

The research team observed that many families had installed private water tanks that were open and exposed to the elements. These water tanks presented a significant threat to public health, having become a breeding source for the Yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti), which lays its eggs in the internal walls of the tanks above the water level.11 These mosquitos help spread viruses, notably Zika, dengue, and chikungunya among the population.12 Zika can be particularly devastating, since it can cause significant birth defects, such as microcephaly and other severe fetal brain defects.12 Beginning in 2015, Zika virus was spreading throughout the Americas and a causal link between Zika virus and congenital malformations was confirmed.13-15 To reduce the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases, community health workers were educated on the relationship between exposure to stored water and increased risk of Zika virus transmission. This education is important because the knowledge attained can empower women to take preventive measures to reduce their risk of infection.

The objectives of this study were 1) to determine El Chacuey’s unmet water needs, current water usage, and plans to maintain a future water system, and 2) to educate the community through its community health workers on the prevention methods to control the transmission of Zika virus.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in El Chacuey, Dominican Republic between January 2019 and March 2019.

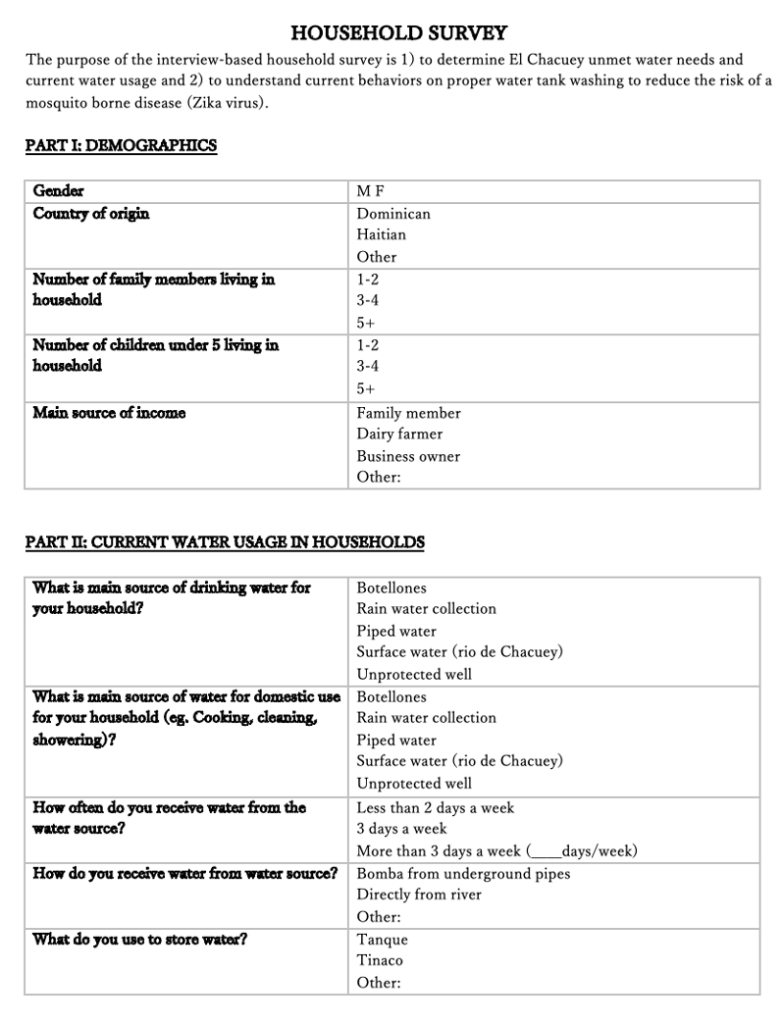

Household Survey

Household surveys consisting of 20 closed-ended questions addressing four broad topics, household demographics, current water usage in households, building a water system, and knowledge of the Zika virus (Appendix A), were administered by a research staff person fluent in Spanish. Survey items were tailored to the local context, but not drawn from validated measures; a local interpreter was not hired due to financial reasons. Participants were selected through criterion-based, purposive sampling, which ensured we identified a diverse range of voices within the community. Incentives were not provided. The data collected from the household surveys were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Of note, the local physician and water committee members were not interviewed individually due to lack of time and funds. A separate, qualitative study can be conducted to further explore these topics.

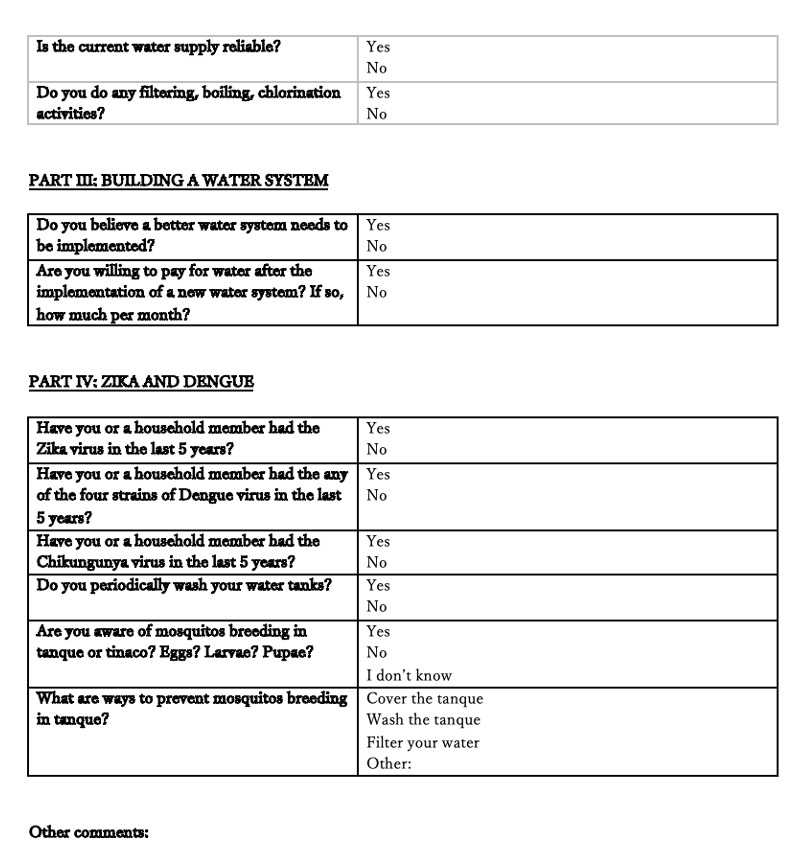

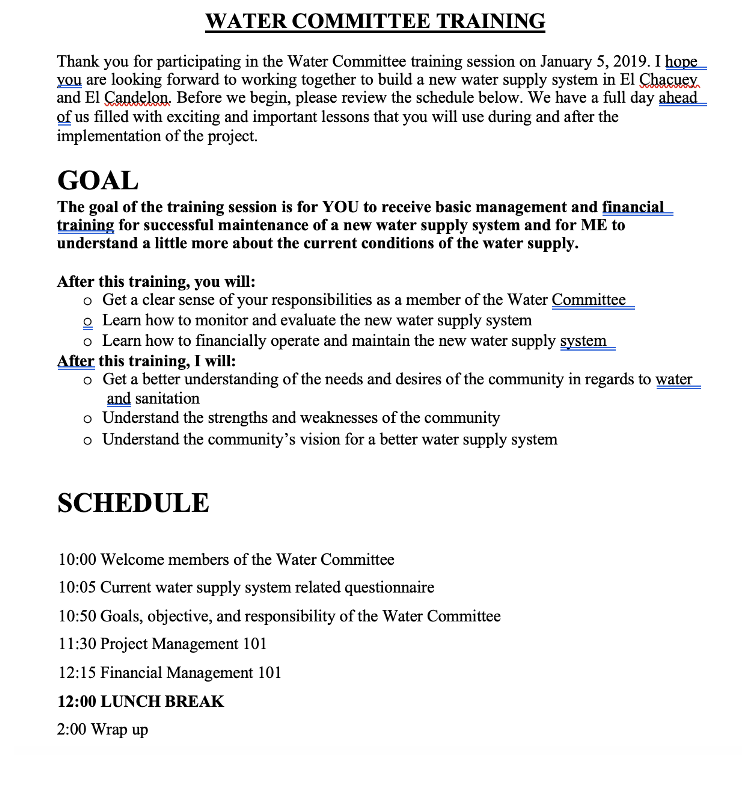

Water Committee Training

The water committee training consisted of four sections, held on the same day (Appendix B). The goal of the training session was for the committee members to receive basic management and financial training to support the maintenance of a new water supply system, and improve understanding of the current conditions of the water supply. The first section involved a questionnaire similar to the household surveys. The questionnaire was divided into three sections: 1) understanding current unmet water needs, 2) learning about the community, and 3) the water committee’s involvement in the water project. The next section described the responsibilities of each water committee member. Each member was asked to share their understanding of their role. The third section detailed the operation and maintenance training once a new water system was built. The last section discussed financial management.

Zika Virus Educational Training

The last tool consisted of educating four community health workers on two topics: 1) the relationship between exposure to stored water and increased risk of Zika virus transmission and 2) the transmission of Zika virus from mother to fetus and its associated consequences. The training was divided into four sections. The first section provided a broad overview of the Aedes aegypti mosquito and its life cycle. The second section gave the community health workers the opportunity to visit three different households to learn how to check for Aedes aegypti eggs affixed to the wall of water storage containers. In the third section, the community’s resident physician demonstrated how to properly clean the water storage tanks using the optimal ratio of chlorine and detergent. The physician based this ratio on their own experiences with cleaning tanks. The fourth section, also taught by the resident physician, addressed the adverse relationship between the Zika virus and pregnancy, and the steps pregnant women can take to reduce their risk of getting bitten by infected mosquitos. The physician was a Dominican woman who provided primary care services to the community including prenatal care and family planning services. At the end of the training, a culturally-relevant brochure was given to the community health workers that discussed the relationship between Zika virus and pregnancy. A brochure was created drawing on staff experience living and working in the neighboring community as a Peace Corps volunteer. Community health workers were instructed to distribute the brochure to local women who plan to participate in future trainings. At the end of the training, a five-question quiz on the topics discussed during the training was administered to measure retention of the information provided.

A total of 73 household surveys were administered in a two-week timespan; 77% of survey participants were women, 97% were Dominican, and 3% were Haitian. Among all households surveyed, 30% had four or more family members living together. 96% of women who were interviewed were homemakers and established their financial security either through their husbands who worked as dairy farmers or through their children.

In terms of water usage, only 22% of participants mentioned that their household received water regularly from the current gravity-fed water system (Figure 1A-C). All participants stated that the water supply is unreliable and that a better water system needs to be implemented. Most said they would be willing to pay a monthly fee for clean water after the construction of the water system. All participants reported using surface water from the nearby river for domestic use, while 58% stored water in tanques (household water tanks). Among those who used tanques, 59% said they cleaned them over seven times-a-month with water and bleach; 60% covered their tanques with metal sheets, plastic covers, or sacos (plastic bags) when not in use. Almost all families drank water from botellones (5-gallon water jugs). Water from the botellones is filtered in the nearby town of Dajabon, in a processing facility called Agua Beller, and are transported by the water company to various rural communities in the Dajabon region once or twice a week.

The last section of the household survey provided information on mosquito-borne diseases. In the last five years, 35% of participants reported having dengue and 2% had chikungunya. No one reported having Zika. Most believed that the best way to prevent mosquito breeding in tanques was to cover the tanques (68%) and wash them (29%). Many participants were unable to detect mosquitoes breeding in their tanques (93%).

Figure 1. Water-related pictures in El Chacuey, Dominican Republic

Legend: A-C shows different ways families collect and store water. D shows the clinic where the Zika training took place. E shows a discussion during the water committee training session.

A five-hour long water committee training session was held on January 5, 2019 (Figure 1D). The training component allowed the members of the water committee to get a clear sense of their responsibilities. Additionally, all participants learned how to monitor, evaluate, and financially operate and maintain a new water supply system.

Four community health workers received training on the Zika virus in the local clinic on March 18, 2019 (Figure 1E). Two community health workers had good knowledge of the Aedes aegypti mosquito and its life cycle. All community health workers were able to check for Aedes aegypti eggs affixed to the wall of water containers and properly clean the water tanks using the right ratio of chlorine and detergent. A total of three cleaning demonstrations were done: one in a household near the clinic and two in two community health workers’ homes. The local physician led the fourth section of the training session regarding the relationship between the Zika virus and pregnancy. The session was a review for all involved. A brochure on the relationship between Zika and pregnancy was handed out and explained to everyone. The community health workers were expected to transmit the information acquired from the training to all households in El Chacuey at a later stage. At the end of the training, the community health workers received a five-question quiz. Three of the four community health workers received 100% on their quiz and one received 80%.

It was clear that many households face water insecurity and that a new water system would greatly benefit the community. To pursue a sustainable and scalable rural water infrastructure, it is important to coordinate actions between households in El Chacuey, technical experts, and international financial donors. Joined efforts from all stakeholders can satisfy all parties’ requests and requirements. Furthermore, by amplifying the community members’ voices, we can equalize the power dynamics among all stakeholders and reduce paternalistic tendencies. This approach can lead to sustainable outcomes, ultimately improving the health and the well-being of the community. Ignoring or disregarding community member input could lead to conflict and resistance, potentially hindering the process of the water project.

After the water committee training session, all members understood their obligations towards the water system. They discussed potential major and minor problems that can arise with a new water supply system, identified local engineers who would be able to help with any damages, and provided the community with information about the potential health benefits of the improved water supply system. One area of concern was the water committee’s ability to financially manage the new water system; due to limited financial reserves and the distance of the community from Santo Domingo, the country’s capital, some components of the new water system may be difficult to obtain or too expensive to purchase. The quality of the materials will have a major impact on the sustainability of the project; therefore, materials should be selectively chosen to appropriately care for the new system. Another area of concern pertained to the involvement of women as members of the water committee. Despite their understanding of the training they received, it was apparent that women would be unable to utilize their newly acquired knowledge due to gender inequality. These women would be excluded from involvement in construction, educational, and financial decision-making processes. This situation leads to a notable absence of representation and engagement from women.

Lastly, it was observed that the physician and the community health workers knew the basic concepts of Zika virus and birth defects. However, this knowledge was not provided to young women in the community. Consequently, the women did not fully know the connection between Zika and birth defects nor the methods on how to reduce this risk. The community health workers need to create an intervention that discusses prevention methods to reduce the risk of mosquito-borne diseases among these women. This will continue to be important because water storage tanks will be used even after the construction of the new water supply system.

The findings of this study contribute to the limited body of research on water quality and mosquito-borne virus transmission education in rural communities in the Dominican Republic, filling a gap int heliterature. It also emphasizes the importance of community engagement; it is essential for NGOs to avoid paternalistic approaches in project design. Instead, NGOs should actively listen to the community and collaborate to develop sustainable projects.

The study also had some limitations, notably a language barrier between research staff and the participants. While one research staff person possessed advanced skills in spoken Spanish, they were not a Spanish speaker, which created some risk that some information regarding current water usage and practices may not have been interpreted correctly. Second, this study was conducted in one small community in the Dominican Republic and should not be generalized to other rural communities in different countries. The study methods should be adapted as needed to different settings. Third, although it was found that there was no incidence of Zika virus within the community, it is still important to take precautions. The household surveys relied on self-reported information and many participants were unaware of the distinction between different mosquito-borne viruses. This can be attributed to limited education and knowledge. The preferred method of diagnosis to verify whether a participant had a particular mosquito-borne virus is through NAAT assay, which was not performed due to lack of funding.

Two recommendations and research ideas are presented in this section. First, it is important to incorporate women in all water, sanitation, and health interventions. Only 38% of the water committee members were women. These women held symbolic rather than substantive roles, giving them little to no responsibility or decision-making capacity. Moreover, many water-related activities are done without women. I recommend equal gender representation in all intervention programs. To pursue this, future research is needed to investigate gender roles and responsibilities of the water supply system as well as gender-focused training methodologies. Additionally, it is necessary to ensure that children are raised with a solid understanding that both women and men possess comparable capabilities in executing and developing projects. Second, the water committee should educate the community on water conservation techniques and monitor water usage in all households. Once a water system is built, water quantity will increase. As a result, household members may leave the water continuously running, causing wastage. This wastage can leave the community in the same situation pre-construction, with not enough available water for everyone. All households need to take responsibility for their water intake and be conscious of wasting the limited water supply.

The families in El Chacuey have poor access to the current water supply. Using the communities’ strengths and assets, a NGO should financially aid the community in building a water supply system. This new water supply system will allow families to do basic domestic activities without worrying about running out of water and will improve health outcomes. In terms of Zika virus transmission prevention, many families should receive education on mosquito-borne diseases from community health workers, regardless of the transmission rates. This information, if given appropriately, can potentially decrease the risk of contracting mosquito-borne viruses.

Appendix A. Surveys conducted with family members in El Chacuey, Dominican Republic

Appendix B. The water committee training schedule

I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Elli Leontsini for her support and involvement in my research project. I would also like to thank the Saint Cloud Rotary Club, specifically Dr. Gary Strandemo and Brian Hart, for giving me the opportunity to be involved in such a wonderful project. It truly was a wonderful experience and I could not have done it without his professional guidance and partnership. Lastly, I would like to thank the entire El Chacuey community for letting me into their homes and sharing their lovely stories with me.

This study was supported by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health MPH Field Experience Fund Award awarded to Rosemary Wright. No competing financial interests exist. The author confirms that this work is original, has not been commissioned, and has not been published elsewhere.

Rosemary Wright is currently a third-year medical student at Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine. She received her Master of Public Health from Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health in 2019.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.