Randolph E, Paturu T, Zhou J, Smith K. Where in the world? in search of the international medical traveler: a scoping review. HPHR. 2024. 87. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/IIII4

Patients who travel from foreign countries to the U.S. to receive medical care occupy a unique niche in the American healthcare system and require additional financial, cultural, and logistical consideration. Medical literature on this population is sparse, and primarily focused on descriptive, ethical, and economic perspectives rather than clinical outcomes. Vague language and a lack of consistent terminology make existing literature difficult to find.

Articles published in the English language on PubMed, Embase, OVID global health, and gray literature from the World Health Organization (WHO) relevant to the care of patients who travel to the U.S. for medical care were examined. Search terms included combinations of ‘international,’ ‘global,’ or ‘non-resident’ patients, ‘medical care abroad,’ ‘medical tourism,’ ‘international program,’ or ’global services.’ Data collected included study type, topic, and the terminology used to describe this patient population.

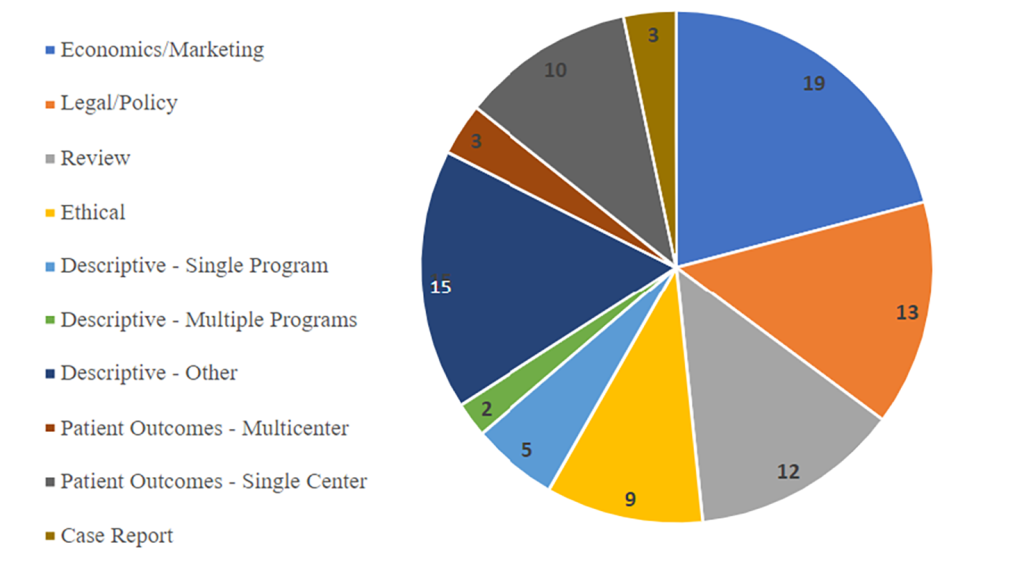

A total of 1564 unique works were identified and 92 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. 76 papers were identified as descriptive while 16 investigated patient outcomes. Descriptive articles were subdivided into economics/marketing (19), Legal/policy (13), Ethical (9), Reviews (12), single center (5) and multi center (2) perspectives, and other (16). A total of 16 investigated patient outcomes, including single-center (10), multi-center (3), and case reports (3). The most popular terminology included medical tourism (50), international patients (24), cross-border care (3), and foreign patients (3).

This scoping literature review offers insight on patients who leave their country of residence to obtain medical care in the U.S. Existing literature is skewed toward articles with a non-medical focus. Further research exploring patient outcomes is indicated. The wider use of clear, standardized terminology such as international medical travelers (IMTs) may help the collection and sharing of data to address gaps in knowledge.

International medical travelers (IMTs) have sought medical care in the U.S. since at least the 1970s, with a large network of U.S. international patient programs established by the 1990s1. The discussion of “international patients” and “medical tourism” is extremely broad, including patients who travel to or from developed countries for procedures that may be more timely or affordable, patients who travel to more developed countries for complex care, patients being studied remotely who do not travel at all, or patients who travel for fertility treatments, cosmetic treatments, and more.2

Most international patients who travel to the U.S. are doing so for services they believe are not available or not of the desired quality in their home country.3 This includes procedures such as complex surgery, comprehensive cancer care, and pediatric care. According to the 2023 report from The U.S. Cooperative for International Patient Programs (USCIPP), 60 unique U.S. organizations served 47,002 international patients and reported 2.1 billion dollars in gross revenue charges in one fiscal year.4

These patients often require additional resources to manage financial clearance, care coordination, and cultural needs, but also tend to bring more revenue to hospitals through payment sources other than domestic insurance.5,6 While a fair amount of research has focused on international healthcare trends and medical tourism, little research has been done on the population of patients who travel specifically from foreign countries to the U.S. for medical care.7,8 Due to the unique niche these patients occupy, data can be difficult to collect. Medical records from these patients’ home countries may be sparse or require translation, and institutions can be financially incentivized not to share information on these patients as they compete for their patronage.9 This deficit in information and scientific inquiry is only magnified among the pediatric subset of this population.10 As the number of international patients traveling to the U.S. for medical care continues to increase, it is necessary to develop terminology and data standards that allow this population to be identified in scientific literature.

This study aims to characterize existing literature and terminology for patients who travel from foreign countries to the U.S. for necessary health care, with the goal of describing this population, their healthcare needs, the quality of outcomes, as well as identify terminology most frequently used and the most effective nomenclature to describe this patient population.

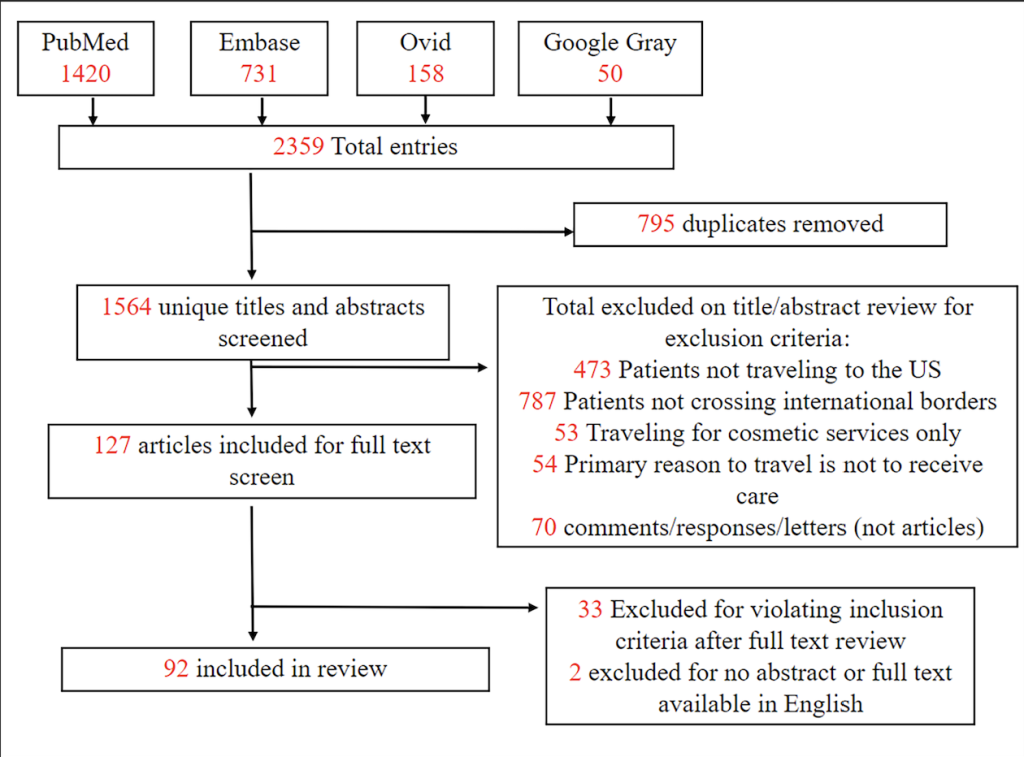

Literature published from January 1950 through May 2023 related to patients who leave their country of residence to travel to the U.S. for medical care was examined. The search was conducted between May 1, 2023, and May 31, 2023, and therefore only includes articles available on these platforms during this period. A total of four scientific databases were searched for literature specific to this patient population, including PubMed, Embase, and Ovid global health, and an additional gray literature search was performed through google to screen for reports from the WHO, ensuring that similar criteria were used for each database with adjustments necessary for the natural language that is supported on each platform. The search terms include ‘medical tourism,’ ‘international patients,’ ‘medical care abroad,’ ‘health tourism,’ ‘international programs, ‘non-resident patients,’ ‘non-citizen patient,’ or ‘international referral’. PRISMA criteria for scoping reviews were followed while collecting and screening articles. Duplicate reports were identified via PMID or DOI and removed in Microsoft Excel. Duplicates of articles were the only articles to be deleted, rather than excluded. After removal of duplicates, the search returned 1420 unique papers in PubMed, and an additional 68 unique papers in Embase, 68 in Ovid, and 8 from the google gray literature review for a total of 1564 unique articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – PRISMA flow chart.

Titles and abstracts were screened with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: Inclusion criteria was defined as articles including patients who leave their home country to seek non-cosmetic medical care, patients whose travel is motivated primarily to receive medical treatment, and patients who seek care in the U.S. Exclusion criteria was defined as: patients who did not travel from their home country, patients whose destination country was specifically stated as not the U.S., patients whose primary motivation to travel was not medical care, literature focused exclusively on cosmetic treatments, search results that were comments or letters instead of articles, or articles not available in full text or with an English translation. Following the title and abstract screening, full articles were screened for inclusion and exclusion independently by two reviewers (Figure 1). As part of full text analysis, reviewers noted terminology used to describe the target population and each article was categorized based on study design and topic. In case of a discrepancy, a third reviewer screened the article to break the tie. After screening for inclusion and exclusion, 127 articles were included for a full text screen.

Article Categorization: To understand the scope of literature available, articles were assigned one main category based on study design and topic. Assignments were based on keywords in the title, abstract, search tags, title of the publishing journal, and full text review. In the event that these presented conflicting themes, titles, abstract, journal, and search keywords were given priority in that order. Categories included patient outcomes (multicenter), patient outcomes (single center), case reports, quality improvement, clinical trials, and descriptive literature. The descriptive literature category was further characterized into subcategories: single program, multi-institutional programs, ethical, legal/policy, economics/marketing, review, and other. Articles were assigned independently by two reviewers. In case of a discrepancy, a third reviewer screened the article to break the tie.

Terminology: The target population, patients traveling to the U.S. specifically for non-cosmetic medical care, are describing using diverse terminology. A single “primary” and unlimited “secondary” descriptors were recorded for each article based on the terminology used to describe this patient population. The “primary” descriptor was identified by inclusion in the title/abstract, by appearing as the first descriptor used within the text, or by specific mention in article keywords or search terms. The “secondary” descriptors included any other unique words or phrases used to identify the patient population within the body of the text.

Of 1564 articles that were included in the review, less than 6% were relevant to the target population. Our exclusion process involved removing papers focusing on patients who did not travel out of their country of residence (50.3%), traveling for cosmetic services only (3.4%), traveling for reasons other than receiving care (3.5%), and those who traveled to countries other than the U.S. (27.9%)

Of the 127 papers included for full text review, 35 were excluded after full-text review for violating inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 76 papers were identified as descriptive, broken down into those that focused on economics/marketing (19), legal/policy (13), ethical (9), reviews (12), single- center (5) and multi- center (2) perspectives, and other (16) (Figure 2). Respective categories are defined below.

Figure 2 – Distribution of Articles by Topic

Literature was considered within the category of economics/marketing if main objective was to explore the ways in which medical travel affects the dynamics of supply, demand, and allocation of resources, as well as strategies employed by groups to promote the medical tourism field.

The majority of articles explored entrepreneurship opportunities in the overarching field of medical tourism and were concerned with factors that drive patient decision making. Early articles from the 1980s identify the market as having the potential to be lucrative, but postulate drawbacks may outweigh the potential benefits for hospitals seeking to enter this business. In the 1990s, researchers highlighted a shift in care practices as hospitals began to compete for international patronage and discussed the development of dedicated international programs. Articles from the early 2000s describe medical tourism as a promising and lucrative market and describe the development of tailored services for international patients by domestic hospitals. Many also discussed allocation of resources, reporting that libertarianism and consumer-oriented attitudes are prevalent, and conclude that the market will allocate healthcare resources efficiently, but not always in an ethical manner.11

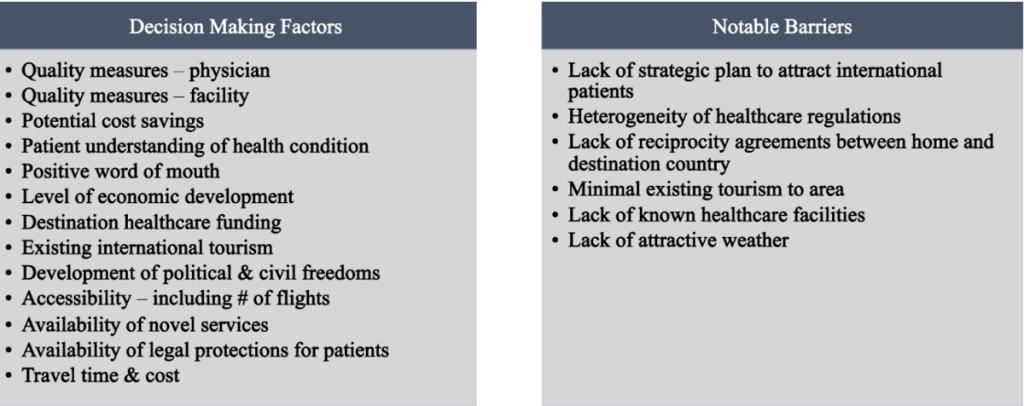

The decision-making process that determines where patients seek care was of particular interest. While these choices are overall very personal and complex, studies found significant relationships between where patients chose to travel and the perceived risk of care in that location.12,13 Other important factors that reportedly affect this decision are detailed in table 1.14–16

Table 1: Factors Affecting Decisions to Travel

More recently, an article written during the COVID-19 pandemic predicted that an uncoordinated public health response to the pandemic may deter future inbound medical travel. Articles also speculated that reforms to the U.S. healthcare system and insurance plans would influence inbound and outbound medical tourism, potentially causing U.S.-based providers to explore new and innovative ways of connecting with international patients.17 Reports raise concerns regarding the effect of global economic instability on tourism markets, health spending in the U.S., and quality of care. Overall, short-term changes in individual markets seem to have minimal effect on the overall state of the global health tourism market, and current literature recommends that spending be informed by long-term development goals instead of acute fluctuations. It was also emphasized that providers, payers, vendors, and other healthcare stakeholders who can efficiently and effectively respond to the crises of the time will be successful in engaging with international populations.18,19

Literature was considered within the category of legal/policy if the purpose of the article was to discuss or explore current or potential laws, regulations, or policies surrounding international medical travel.

While describing legal policy in detail is outside the scope of this review, a bibliometric analysis in 2020 concluded that only a small proportion of medical tourism research explicitly addresses policy issues and that these articles are skewed towards specific policy areas such as reproductive and transplant tourism. However, they neglect broader applications such as holistic governance and specific health system considerations.20 Many articles discuss challenges related to establishing legal jurisdiction, enforcement, and limitation in the accreditation of international facilities and note that patients often shoulder the full legal burden. It has been suggested that regulation may be best achieved by home country governments and that patients who rely on insurance are often easier to regulate than patients paying out-of-pocket.21 However, overly cumbersome legal requirements, such as barriers to obtaining visas for travel can lead to delayed treatment and worse patient outcomes.22 Additionally, these barriers are magnified for individuals hailing from low-income countries with limited resources to navigate cumbersome U.S. immigration policies, who otherwise lack access to what may be necessary and life-saving care.

Healthcare globalization creates opportunities for patients and physicians, from both the giving and receiving health systems, but also creates concerns for biosecurity in terms of disease transmission, healthcare access, and assumed legal risk.23 Currently, there is a lack of uniform regulations addressing patient, provider, charitable, non-governmental organization, or institution liability, scope of confidentiality, and follow- up care. The U.S. does offer an increased degree of protection for inbound patients because our system does offer avenues for patients to seek legal recourse for medical harms, which many other countries do not provide. International accreditation standards such as those from the Joint Commission International create a good foundation but indicate much work for the future.

Literature was considered within the category of legal/policy if the purpose of the article was to discuss or explore current or potential laws, regulations, or policies surrounding international medical travel.

While describing legal policy in detail is outside the scope of this review, a bibliometric analysis in 2020 concluded that only a small proportion of medical tourism research explicitly addresses policy issues and that these articles are skewed towards specific policy areas such as reproductive and transplant tourism. However, they neglect broader applications such as holistic governance and specific health system considerations.20 Many articles discuss challenges related to establishing legal jurisdiction, enforcement, and limitation in the accreditation of international facilities and note that patients often shoulder the full legal burden. It has been suggested that regulation may be best achieved by home country governments and that patients who rely on insurance are often easier to regulate than patients paying out-of-pocket.21 However, overly cumbersome legal requirements, such as barriers to obtaining visas for travel can lead to delayed treatment and worse patient outcomes.22 Additionally, these barriers are magnified for individuals hailing from low-income countries with limited resources to navigate cumbersome U.S. immigration policies, who otherwise lack access to what may be necessary and life-saving care.

Healthcare globalization creates opportunities for patients and physicians, from both the giving and receiving health systems, but also creates concerns for biosecurity in terms of disease transmission, healthcare access, and assumed legal risk.23 Currently, there is a lack of uniform regulations addressing patient, provider, charitable, non-governmental organization, or institution liability, scope of confidentiality, and follow- up care. The U.S. does offer an increased degree of protection for inbound patients because our system does offer avenues for patients to seek legal recourse for medical harms, which many other countries do not provide. International accreditation standards such as those from the Joint Commission International create a good foundation but indicate much work for the future.

Some degree of overlap is appreciated between the ethical and legal/policy space. Literature was considered to fall under the ethical category if the main discussion focused on moral or ethical dilemmas concerning international medical travel.

Ethical discussions include the practice of “circumvention” tourism, in which patients travel to access services not legal in their home country, as well as transplant tourism and broader discussions related to equitable allocation of resources and justice for local communities.24 Discussions relating to circumvention tourism echo tensions between conservative and progressive ideals, as patients travel from more restrictive countries to those with more social freedoms to receive services like IVF or abortion, as well as the potential for patients who travel for such services to face punitive action after returning home. Discussions of transplant tourism change focus depending on country income status, detailing the potential for patients in low-income countries to be taken advantage of in the organ trade to provide organs for wealthy tourist-consumers. In more developed countries, ethical considerations are focused on equitable distribution of resources, as entering medical travelers consume resources from the limited organ donation pool as well as appointments, materials, imaging, and time with medical staff, but also provide resources by bringing significant financial support to hospitals that rely on full-paying customers to fund other care that benefits the local community. An article from 2011 describes a social responsibility of the traveling patient in their new community and the duty of the incoming tourist to use health resources efficiently and engage in activities that promote the health of that receiving community in return.25 Others call for an allocation system to reconcile supply and demand regarding international pediatric organ transplant to capture the impact that international patients may have on the local system,24 as well as improvements in the current framework regarding informed consent discussions with IMTs to address medical tourism.26 Suggestions are provided to caregivers in regard to performing ethical and values-based patient- centered care when interacting with international patients. This includes particular attention to the patient’s personal values instead of making assumptions based on ethnicity or religion, as well as realigning expectations, identifying ethical conflict, acknowledging moral distress, and improving coordination of care through existing hospital resources, including relevant embassies.9

Year after year, reviews identify similar deficits in our knowledge base, seeking more information about who these patients are, what drives their decision-making, where they get their information, how they impact our healthcare system, and data on patient outcomes.27,28 Since 2010, we have seen some reviews and individual studies contribute to our understanding of population demographics, patient motivations for travel and decision- making, as previously discussed. We also appreciate the beginning of efforts to understand the role of the internet and media in this decision-making process, as well as the dynamics of medical tourism between Europe and Asia, which is outside the scope of this review. One systematic review from 2019 included 43 publications on medical tourism, with only a small minority addressing patients who travel to the U.S. for care. The U.S. was characterized as a leader in providing stem cell therapies and noted to have a significant increase in patients coming to the U.S. for reproductive care.29

Data on outcomes for medical tourist treatments is limited. Some suggest the creation of a common regulatory platform and reporting system to establish a consistent method to assess quality and allow for comparison and accreditation. Two reviews discuss the conceptual ambiguity facing “medical tourism” more in- depth. Both propose similar definitions for “health tourism,” which involves traveling to enhance wellness, and “medical tourism” which specifically includes the receipt of healthcare while abroad. They identify a difference between medical tourists who travel for elective or cosmetic procedures and those who travel for necessary care, but do not apply specific terminology to delineate these two populations.30,31

Literature was considered to fall under the category of single and multi-center perspectives if the main discussion detailed perspectives and guidance from institution-based international and global services programs. Early works include descriptions of early pioneering international programs at destination academic centers.32 Newer works share updates to the workflow of an international patient’s journey from intake to treatment and home-country follow-up. Key infrastructure includes thorough intake before the patient is approved to engage in travel, development of service menus and financial estimates, care coordination, translation, logistical support, relationships with the patient’s companions and caregivers, partnerships with international payors and embassies, and methods of obtaining follow-up care after return to the home country. There has also been interest in sharing successes and challenges encountered when caring for international patients, including considerations related to cultural competency, security, companions and caregivers, and logistics.33

Challenges for international medical travelers include isolation from their normal support system, language and cultural barriers, intake and obtaining records, wait times and transportation to distant facilities, culturally sensitive examinations, volume challenges in an already limited system, continuity of care and transition home, and follow-up care.5,7

The reported benefits of providing care for international patients include expanded medical and cultural knowledge, the value of providing access to those previously unable to receive necessary care, increased patient volumes, relationships with international facilities and embassies, increased reimbursement rates compared to local insurance, and is often described as rewarding and fulfilling by interdisciplinary care teams.

Outcomes literature includes scientific investigation of a population of patients focusing on clinical interventions and outcomes. A total of 16 articles investigated patient outcomes, including single-center studies (10), multi-center studies (3), and case reports (3). No articles were identified as quality improvement initiatives or clinical trials. Literature on patient outcomes covered a broad range of topics including infectious disease (4), radiation therapy (2), cardiac surgery, reproductive travel, transplant medicine, hematology/oncology, burn care, diabetes, end of life care and multiple sclerosis. Sample size for these studies ranged from 4 to 1237.

There is particular interest in the infectious risk associated with cross-border healthcare. One review assessed 49 articles on medical tourism-related infections relating to cosmetic surgery and organ transplantation and included a mix of low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Wound and blood-borne infections were most common with a prevalence of mycobacteria pathogens. The authors caution that choices of medical tourists could not only impact the patients themselves but also the public health of their home countries.34 Other articles also reported increased prevalence of colonization with multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae amongst IMTs, and toxoplasmosis,35 and provided guidance on antibiotic selection for international burn transfers.36 A second article on burn wounds found that high voltage burns in international patients were generally more severe than those in domestic patients, were associated with much longer lengths of stay, and had increased risk of infectious complication. Burns in international patients were commonly attributed to poor education and infrastructure, and investigators identified a need for improved electrical safety regulation to decrease occurrence of these severe but very avoidable burns.37 A 2011 retrospective case-control study investigated the relationship between length of stay and payment source for both IMTs coming to the U.S. and domestic patients. Overall, international patients were staying longer than domestic patients, with complex international patients having substantially longer length of stay than their domestic counterparts. However, there was no observed difference in length of stay based on the IMT’s payment source (self-pay vs. Insurance types).38 Two oncologic studies found that changes to radiation therapy protocol made to accommodate international patients’ tighter timelines were efficacious and safe,39 and that allowing minor delays in access to proton beam therapy for children with medulloblastoma to undergo rigorous pre-travel intake did not affect patient outcomes and validated appropriateness of traveling for such treatments.40 These investigations highlight the value of clinical outcomes research that focuses on medical travelers or international transfers, as takeaways can extend beyond care delivered within U.S. borders and also identify opportunities for interventions abroad.

“Other” descriptive literature consisted mainly of individual patient (3) and professional (7) perspectives on current issues in the field, discussions related to terminology (2), the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on the industry (2), as well as commentary on the role of websites and media and further discussions related to patient decision making.

The most popular primary descriptors were medical tourism (50), international patients (24), cross-border care (3), and foreign patients (3). The most popular secondary descriptors were international patient(s) (19), medical tourism (17), medical tourist (9), foreign patients (10), international medical traveler (5), health tourism (4), circumvention tourism (4), international healthcare (3), international services (3). Other, less frequently used descriptors are also detailed in table 2.

Table 2 – Primary and secondary terms to describe the target population of patients traveling to the U.S. for non-cosmetic medical care.

Primary Terms | # articles |

| Secondary Terms | # articles |

medical tourism | 40 |

| international patient(s) | 19 |

international patients | 23 |

| medical tourism | 17 |

medical tourist(s) | 10 |

| foreign patients | 10 |

cross-border (care, treatment) | 3 |

| medical tourist(s) | 9 |

foreign patients | 2 |

| international medical traveler(s) | 5 |

healthcare travelers | 2 |

| circumvention tourism | 4 |

international medical traveler(s) | 2 |

| health tourism | 4 |

reproductive travelers | 2 |

| international healthcare | 3 |

transplant tourism | 2 |

| international services | 3 |

health tourism | 1 |

| transplant tourism | 2 |

transnational healthcare | 1 |

| circumvention tourist(s) | 1 |

travel medicine | 1 |

| cross-border care | 1 |

medical travelers | 1 |

| international healthcare | 1 |

|

|

| international inpatients | 1 |

|

|

| reproductive travelers | 1 |

|

|

| vaccine tourist | 1 |

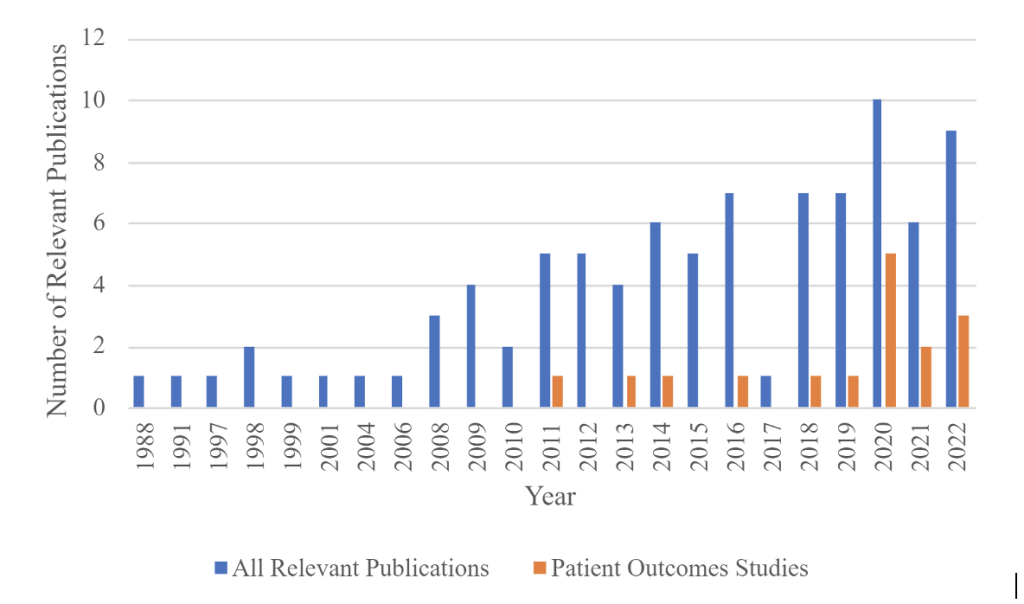

The number of articles published by year was also recorded. The first included article was published in 1988, and the first article relevant to patient outcomes was published in 2011. Please refer to Figure 3 to review the scope of relevant publications.

Figure 3 – Publications by Year

This scoping review aimed to characterize existing literature that addresses patients who travel from foreign countries to the U.S. for necessary health care, to determine the focus and distribution of topics covered by these articles, and to identify the array of terminology used to describe this patient population. Our study revealed that much of the existing literature focuses on descriptive analysis addressing economics, public policy, and ethics, and there is a lack of investigation into clinical process and outcomes. This echoes the gaps described 15 years earlier,27 though the steady rise in publications about IMTs overall since 2011, and clinical outcomes over the last 3 years, indicates increased interest in the field.

Our inquiry reveals that existing literature is difficult to access with the terms currently accepted to describe this patient population. The most popular, currently being “medical tourism,” “international patients,” and “foreign patients,” are nonspecific and more aptly describe unrelated activities such as travel for elective cosmetic procedures or patients who live abroad but do not engage in travel. The term “medical tourism” often describes patients who travel to pursue decreased costs or waiting time, and often involves movement from a more developed health system to a less developed one. The terms “international patients” and “foreign patients” are often used to describe a remote analysis performed on patients who reside in another country but do not engage in travel. The word tourism itself inherently implies travel for “pleasure” or “relaxation” which is referenced in many dictionary definitions, and these descriptors are not accurate to describe our target population for whom travel is motivated primarily by medically necessary healthcare.

Searches were further complicated by the database Medical Subject Headings (MESH) thesaurus which is used for cataloging search terms that may be used to index articles, as it does not officially recognize many of the terms to appropriately address this population. We used search terms based on our research, as well as from those in the articles we identified not flagged as official search terms. MESH did not return results for “international patient,” “foreign patient,” “IMT,” or “medical traveler.” “Medical tourism” is an official term that is linked to subcategories of economics, ethics, history, legislation and jurisprudence, organization and administration, psychology, standards, statistics and numerical data, and trends. It is officially linked to “health tourism,” “surgical tourism,” and “medical tourist.” These terms still fall under the misnomer of “tourism,” which is inappropriate to describe IMTs as they travel specifically for medically necessary care. MESH also includes the keyword “international agency,” which refers to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Red Cross and the United Nations (UNS), and “international education exchange.” MESH, however, does not mention international travel specifically for healthcare or agencies that facilitate this kind of care.

We focused specifically on literature referring to patients who travel to the U.S. under the assumption that motivations or patient outcomes may differ when traveling to other countries or with different motivations. Many patients and professionals alike believe that few countries can compete with the quality of innovative and complex care provided in the U.S.41 This highlights existing disparities in global healthcare access that may both result from and perpetuate historical inequities. Ethical and policy discussions reveal two distinct responsibilities regarding IMTs. Firstly, providers and the U.S. health system have a responsibility to ensure the best possible care for patients who currently travel to the U.S. This goal is unachievable without data to investigate clinical outcomes, which cannot be appropriately collected without clearly defining this patient population. The second layer of responsibility involves furthering equitable access to healthcare locally and globally. While caring for IMTs provides necessary care they would otherwise lack, current structures favor access to patients who have the means to fund themselves or are supported by governments who can fund travel for care. This disadvantages patients from low to middle income countries, who may experience significant barriers related to cost and medical or political literacy and may be vulnerable to predatory practices by incoming travelers or non-governmental organizations. This also raises questions about the appropriate distribution of resources between local and visiting patients. Many existing discussions address this population of patients as a larger group combined with medical tourists though they have distinctly different characteristics, needs, and vulnerabilities. Creating the infrastructure to further develop this field, starting by appropriately defining this population, would lay the groundwork to more deeply explore questions related to patient outcomes, social justice, and equity in medical travel.

Three articles have identified similar challenges and proposed terms for this population of patients, including “movements for healthcare,”42 “medical travelers,”43 and “international medical travel.”2 We have demonstrated that without a standard definition for this population, researchers, providers, international agencies, and others face challenges in collecting and sharing data about patients seeking care abroad. These circumstances create significant barriers to understanding industry changes and monitoring patient outcomes.44 “International medical travel” was first proposed as an alternative to medical tourism by Horowitz and Rosenweig in 2008, but the original article did not appear in the search conducted above or independently on PubMed, Ovid, or Embase at the time of this article. Few articles have adopted this term over “medical tourism” or “international patients,” however the authors of this study see the value in the phrase “international medical travelers” (IMT) as being appropriately separated from the idea of “tourism,” while still emphasizing the nature of travel motivated by necessary care and involving cross-border movements.

The objective of this study highlights the limitations related to identifying articles that address international medical travelers. While we have attempted to conduct an exhaustive search, it is possible that additional papers addressing this population using nonspecific language or terms outside our search may have been missed.

As volumes of international medical travelers coming to the U.S. increase, we anticipate a continued economic and academic interest in this patient population. There has been significant growth of international programs to treat IMTs due to both profitability of programs and increasing global interconnectedness.9,10 Existing articles have proven that the study of clinical outcomes for this population is both possible and valuable, but also revealed gaps in data that are exacerbated by ambiguous terminology used both by investigators and search engines. Further inquiry into patient outcomes, improved data collection, and a needed understanding of equitable access to care and social justice implications depend on the more universal understanding of the definition of this patient population and its distinction from medical tourism. A more universal use of specific terminology, such as international medical travelers, would greatly benefit this growing field and the patients who travel thousands of miles for care.

Thank you to the University of South Florida RISE office for their non-financial support and mentorship in the development of this project.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Ellie M Randolph, BA is a Graduate Student at the University of South Florida. Her research areas of interest include international medical travel, global health, and surgery. She received her undergraduate education at Princeton University and is receiving medical education at the University of South Florida College of Medicine.

Dr. Karen Smith MD, MEd is the medical director of Global Services at Children’s National Hospital and associate professor of pediatrics at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. Dr. Smith is board certified in pediatrics and pediatric hospital medicine. Her career began as an army nurse at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Her service as an officer in the U.S. Army earned her several awards including the Army Commendation and Meritorious Service Medals. She received her formal training at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Children’s National Hospital. She is a master teacher and obtained her Master’s in Education from The George Washington University. At graduation she was awarded the Nadler Leadership Award. Throughout her career she has held many leadership positions to include chief medical officer at The HSC Pediatric Center, chair of the District of Columbia Children with Special Healthcare Needs Advisory Board, medical director of School-Based Telehealth Programs, chief of Hospital Medicine and president of the medical staff at Children’s National Hospital. In honor of her contributions to hospital medicine she was awarded the 2020 Excellence Award in Clinical Leadership by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Tejasvi Paturu, BS is a Graduate Student at the University of South Florida. Her research areas of interest include global health and ophthalmology. She received her undergraduate education at Rice University and is receiving medical education at the University of South Florida College of Medicine.

Jennifer Zhou, B.S. is a Graduate Student at the University of South Florida. Her research areas of interest include global health, anesthesia, and radiation oncology. She received her undergraduate education at UCLA and is receiving medical education at the University of South Florida College of Medicine.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.