Hummel C, Kham F, Nguyen-Truong C, Hoeksel R. Culturally inclusive and gender sensitive menstrual health education: nursing and immigrant and refugee community organizational partnership. HPHR. 2024. 87. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/IIII2

Corresponding Author: Dr. Connie K Y Nguyen-Truong, [email protected]

Worldwide period poverty results in gynecological infections and poor outcomes increased menorrhagia, or infections (candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis). Immigrants and refugees have minimal menstrual health education due to cultural taboos, inability to afford feminine hygiene products, and inappropriate use of menstrual reusable products or previous sanitization teachings. The Immigrant & Refugee Community Organization (IRCO) needed evidence-based interventions to reduce period poverty via a culturally sensitive, and gender-affirming menstrual health hygiene program. The purpose of the menstrual health dignity scholarly project intervention was to increase knowledge, comfort, and confidence of community health staff educators (CHSEs) to provide effective client teaching

The Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory, Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Model, and popular education interactive strategies guided the academic-community scholarly project partnership. Developed a cross-sectoral academic-community team partnership with CHSEs buy in; modified teaching in 2 PDSA cycles (100% attendance of at least 2 sessions); and used Power Points for lesson content, case studies, and technology to reinforce learning and menstrual cup and health brochure to increase CHSEs’ knowledge.

Questionnaire scores showed increases of: knowledge (96% in at least 3 categories), confidence (100%) with increased capacity to provide appropriate menstrual health hygiene teaching, products, handouts, and guidance based on appropriate assessments. The results showed 92.3% overall positive comments about the menstrual health education provided including expressing enthusiasm for teaching menstrual health to all genders. Overall, 85.7% of people agreed they would use the information learned in this project for future work and found the education valuable.

The addition of menstrual health trainings with interactive popular education increased CHSEs’ knowledge, comfort, and confidence. Sustainability efforts included recorded lesson content education and encouragement to provide the menstrual cup and health brochure to refugee families upon agency admission.

Overcoming barriers to period poverty includes access to clean water and sanitization hygiene (WASH) facilities, access to private toilets, feeling safe in toilets to change menstrual products, ability to afford menstrual products, access to hormone contraception and relief of anxiety related menstruation.1-4 In Oregon, the Menstrual Dignity Act addresses period poverty due to four out of five students missing class time or knowing someone who did because of little access to menstrual products. Proper menstrual hygiene/health and menstrual cups can reduce infections (bacterial vaginosis [BV], urinary tract infections [UTI], vaginal candidiasis, and toxic shock syndrome [TSS]); therefore, reducing poor health outcomes.5-8 The Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization (IRCO) identified a need for evidence-based interventions to reduce period poverty via a culturally sensitive, and gender-affirming menstrual health hygiene program. IRCO is located in the United States Pacific Northwest and is a non-profit organization striving to provide resources to displaced families and individuals. IRCO provides advocacy and cultural and linguistic needs to persons in over 50 different languages. The public Washington State University (WSU) College of Nursing and IRCO partnership was developed in response to a need to meet the Menstrual Dignity Act and develop training due to poor refugee and immigrant outcomes such as increased BV rates, UTI, and TSS.

At the time of the scholarly project, the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Family Nurse Practitioner (first author) was a Student Scholar who led the academic-community partnership with the overall purpose to provide evidence-based interventions to reduce period poverty and poor menstrual health related outcomes by way of a culturally sensitive, gender-affirming menstrual health education program at IRCO. The goal was to reduce poor menstrual health-related outcomes in the multi-racial population served by increasing the knowledge, comfort, and capacity of the organization’s immigrant and refugee community health staff educators (CHSEs) about the Menstrual Dignity Act HB3294,9 culturally sensitive menstrual hygiene care, menstrual cup use, and recognition of the indications for gynecological referral.

We expected attendance would increase capacity of the CHSEs to provide appropriate menstrual health hygiene teaching, products, handouts, and guidance based on appropriate assessments. Our team partnership’s project aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including goals 1) no poverty, 3) good health and well-being, 4) quality education, 5) gender equality, 6) clean water and sanitation, 10) reduced inequalities, and 12) responsible consumption and production.10

The methods for implementing the menstrual health project included use of the Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory to guide in-person and video conferencing (i.e., online) learning sessions that were integrated with technology features and interactive case studies. The implementation of learning proliferated over time with use of Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory where leaders emerged throughout case studies. This theory utilizes new products and ideas or behaviors to integrate within a social system or human behavior.11 The theory is spread (i.e., diffused) with key ideas, including adopting new innovation as more purposeful than the piece it replaces, compatibility to meet the needs of the adopters, complexity such as product use, triability, and observability (e.g, tangible results).11Inovation has the following 5 categories: the innovators (risk takers), early adopters (leaders of the new innovation), early majority (willing to adopt after evidence shows success), late majority (only try after proven successful), and laggards (skeptical and traditional and can lead to adoption only after people besides themselves have tested the innovation).11 Interaction and emphasis of menstrual health had a rippling effect throughout CHSEs.11 The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Model was adopted from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and guided the scholarly project implementation for 2 PDSA cycles. Each PDSA cycle was implemented in 4 steps as a way to test a change.12 The duration needs to be brief to learn what is working or not and to refine each cycle for a better change.12 In the Plan step, “Describe objective, change being tested, and predictions. Need to breakdown into action steps. Plan for data collection.”12 In the Do step, “Run the test. Describe what happens. Collect data.”12 In the Study step, “Analyze data. Compare outcomes to predictions. Standardize what learned.”12 In the Act step, “Decide what is next. Make changes and start another cycle.”12

At WSU College of Nursing, there are formal project guidelines with participation with any agency that undergoes an ethical review with approval by the WSU College of Nursing DNP Faculty Program Director. The scholarly project was approved according to this formal process. The IRCO Community Health Worker Coordinator (second author) obtained all consent from CHSE participants for project sustainability and recorded content

The scholarly project is a cross-sectoral partnership that consisted of the DNP Student Scholar (project leader and first author), IRCO agency mentor (second author), secondary nursing and community participatory specialist mentor (third author and senior author), nursing faculty mentor (fourth author and senior author), and two to three additional IRCO community health leaders meeting weekly and/or monthly. We used Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory, PDSA Model, and popular education interactive strategies for project implementation. The project team partnership met bi-monthly until implementation of PDSA cycle 1 progressing to monthly meetings. Concerns were addressed throughout the team partnership meetings and teaching refined via feedback in an encouraging and supportive environment for further exploration on topics and teachings. The team partnership planned, developed, implemented, and evaluated a culturally sensitive, gender-affirming menstrual health hygiene education program that included menstrual health training implemented over 2 PDSA cycles (up to 19 in-person participants on October 3rd, 5th, and 7th of 2022). The PDSA cycle 2 was modified with video conferencing (zoom; up to 35 participants, January 25th of 2023) to decrease transportation and childcare barriers.

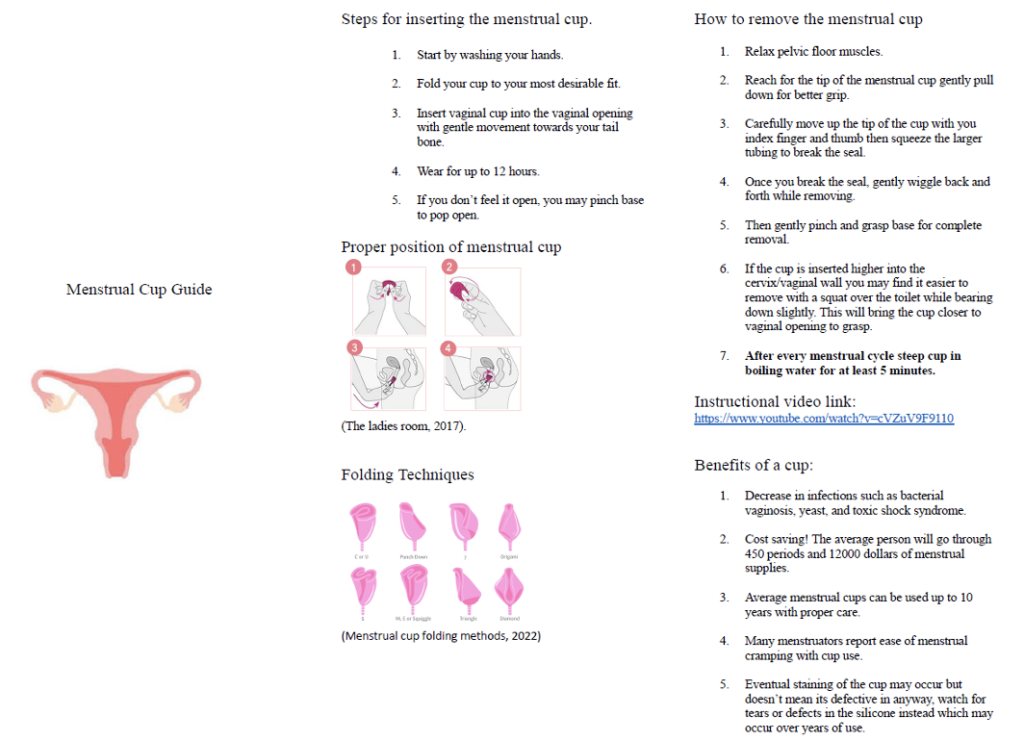

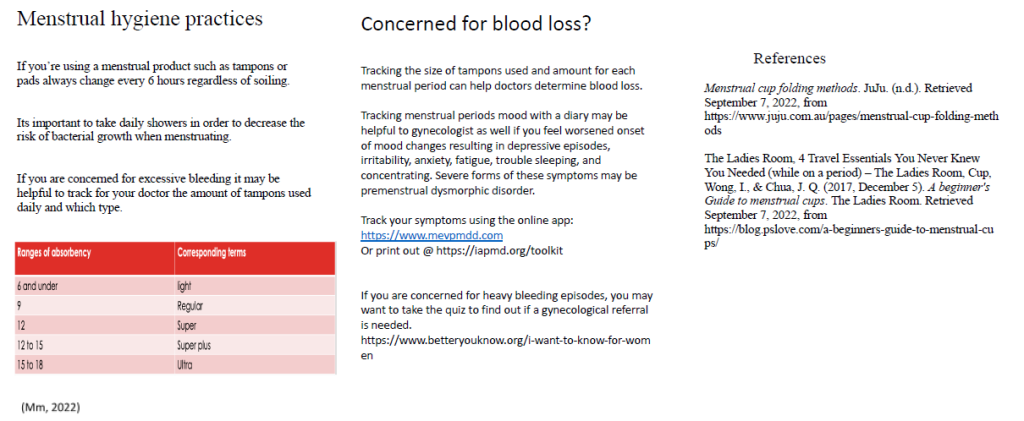

The education was designed with Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory, including consideration of health care literacy, alternative synonyms to minimize language barriers, and popular education interactive strategies tailored to IRCO adult learners. Refer to Table 1 for the Series of 3 Menstrual Health Training Sessions: Learning Objectives, Topics, and Resources. Small discussion groups and case studies were CHSE-led with DNP Student Scholar input. (Refer to Textbox 1 Menstrual Dignity Act Case Study 1, Textbox 2 Assessing Menses’ Case Study 2, and Textbox 3 Gender Affirming Case Study 3. The menstrual cup and health brochure with education video links were developed in response to IRCO CHSEs request within the first two teaching sessions. Refer to Figure 1. Menstrual Cup and Health Brochure. The lesson menstrual health content Power Point teaching developed by the DNP Student Scholar was shared briefly then interactive platform education was implemented for the adult learners to help increase CHSEs’ knowledge, comfort, and confidence. The academic-community project team partnership that included nursing faculty experts and immigrant and refugee community health experts reviewed the content for utility.

Table 1. Series of 3 Menstrual Health Training Sessions: Learning Objectives, Topics, and Resources

Menstrual Health Training Sessions

| Learning Objectives and Topics |

Session I: New Law in Oregon Driving These Lessons and Introduction to the Menstrual Dignity Act

| Learning Objectives:

Topics:

Resource References Hennegan J, Winkler IT, Bobel C, Keiser D, Hampton J, et al. Menstrual health: a definition for policy, practice, and research. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2021;29(1):1911618. doi:10.1080/26410397.2021.1911618

|

Session II:

Update on Products and Practices with Introduction to the Menstrual Cup

| Learning Objectives:

Topics:

Resource References:

|

Session III:

Review of Changing Ideas of Menstrual Health and Gender Affirming Care Practices

| Learning Objectives:

Topics:

Resource References: National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. LGBTQIA+ glossary of terms for health care teams ” LGBTQIA+ health education center. LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. 2020. Accessed February 29, 2022. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/publication/lgbtqia-glossary-of-terms-for-health-care-teams/

|

Textbox 1. Menstrual Dignity Act Case Study 1

The Menstrual Dignity Act was created to relieve period poverty (menstrual education, hygiene facilities, waste management, and access to menstrual products) and help decrease the gap in affording supplies. In Oregon, 1 in 4 young menstruators miss school, at least one day a month, due to menstrual related issues. The Dignity Act has required all schools to have gender neutral bathrooms with menstrual products available in all restrooms by 2023. As staff members, menstrual health education will help serve all families and cultures especially with changing bathroom conditions. Some clients will have questions such as elementary schools with menstrual supplies or the change in gender neutral bathroom signs.

|

Textbox 2. Assessing Menses’ Case Study 2

Enhancing self-efficacy, health literacy, and resiliency through the adaptation of structured There are many menstrual disorders that may need to be addressed and often not discussed. Frequently menstrual abnormalities are not discussed with health professional or within some cultures, further leading to lack of gynecological care. Up to 20% of refugees have endometriosis or other menstrual related disorders not diagnosed. Premenstrual Dysmorphic Disorder (PMDD), Endometriosis, Menorrhagia (excessive bleeding over 80 milliliters), BV, yeast, and urinary tract infections can be overcome with proper menstrual management. Proper menstrual management includes providing resources such as tampons or pads (must be changed every 6 hours), menstrual cup education, PMDD tracking, CDC assessment tools and guidance with gynecological referral. Part of menstrual health is educating families and others to overcome the taboo of menstruation. Not talking about menstruation leads to increased shame and false information often passed down from trustworthy peers or family members. Scenario 1: Mia is a 13-year-old female refugee, she just started her period.

|

Textbox 3. Gender Affirming Case Study 3

Purpose: The Menstrual Dignity Act requires menstrual products and dispensers must be installed in at least two student bathrooms by 2021-22 and in all school bathrooms by 2022-23. Products and dispensers must be provided in a safe, private, accessible, and gender-affirming manner. All people need diverse community guidance regarding access to menstrual supplies with intimate and complex conversations regarding supplies in every bathroom as a community leading the way for inclusion of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Ally (LGBTQIA+). Regardless of sexuality, gender, or identity, an individual can choose any bathroom: this can end period poverty by making supplies available to everyone. Questions for discussion:

Tip: During the conversation ask for pronouns to honor the individual wishes and preferences.

|

Figure 1. Menstrual Cup and Health Brochure (pages 1-2)

The first PDSA cycle consisted of 19 participants during October 3rd, 5th, and 7th of 2022 and was designed at a low level of health literacy to achieve integration of learning and address CHSEs’ language barriers. Session 1 consisted of in-person learning conducted over 2-hour time blocks, addressing the Menstrual Health Dignity Act (Law 3294), the use of the menstrual cups, measuring amount of menstrual blood loss, strategies for helping families and clients identify abnormal (i.e., unexpected) amounts of menstrual blood loss, and methods for providing inclusive language. The 2nd and 3rd session occurred both in-person and over zoom due to expressed socioeconomic barriers of transportation. The session addressed screening tools to help identify premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) including the CDC menstrual tool for menorrhagia and cup insertion techniques. The 3rd session consisted of the Menstrual Dignity Act gender affirming requirements, including inclusive bathrooms, and addressing gender affirming scenarios and questions in a non-biased way and language to create inclusion of all within the menstrual health movement.

The PDSA cycle was split into three sessions each including case studies, material review and online interactive technology with a quarter of the CHSEs attending. Eventually leaders emerged and the CHSEs’ attendance of sessions began to grow with 100% of CHSEs attending at least two sessions. The CHSEs were given pre- and post- menstrual health questionnaires via online through the WSU Qualtrics platform to evaluate increased knowledge of the menstrual health topics including menstrual cup use. DNP Student Scholar-developed menstrual health questionnaires were reviewed by the academic-community team partnership for clarity and utility (details are in the evaluation section). Interactive technology via online Kahoot was designed with game like features and included scores, multiple questions, true or false questions, and demonstrates outcomes for improved repetition, recite, and recall of overall learning topics.13 The overall feedback for implementation of the sessions with lesson content training, case study, and Kahoot group or individual learning resulted in 93% overall positive rates between 25 participants evaluated over 2 PDSA cycles. The results were analyzed using descriptive statistics with anonymous grouped responses to protect confidentiality and stored in a secure University platform.

The case studies included 3-10 questions focused on gender affirming language, menstrual health responses, and use of the menstrual cup. The first case study was developed on addressing barriers and stigma around menstrual periods including introduction of the Menstrual Dignity Act. The intention of the case study was to integrate education of refugees experiencing disproportional disparities including 20% undiagnosed endometriosis, PMDD, menorrhagia, BV, yeast, and urinary tract infections. The taboo of menstruation was addressed with educational scenarios addressing the sensitivity of the topic while empowering women to seek medical care or provide tools for acquiring gynecological care.14 The third case study focused on the requirement of all gender affirming bathrooms including LGBTQIA+ and gender diverse community guidance. The importance of ending period poverty was emphasized with all genders educated throughout the case studies. All case studies attempted to address overall barriers seen in culture including cultural taboo while educating on the Menstrual Dignity Act.

Furthermore, other teaching tools were provided including a brochure for menstrual cup instructions with estimates of blood loss, insertion techniques, benefits of menstrual cup use, and instructional videos. The brochure was designed to accompany the menstrual cup donation supplies to be disbursed by CHSEs to families. Additional tools included links addressed in the training session for the premenstrual symptom tracker utilizing ia-pmd Me-PMDD, a free tracking app or print out of daily record over 2 months for evaluation of PMDD severity.15

Techniques also included familiar key cultural learning concepts of popular education (i.e., empowerment education) were adopted into the sessions. The popular education interactive strategies were to acknowledge cultural practices and introduction within the group setting. CHSEs were asked prior to every session to introduce themselves using Naranja and Pina and Sea, Land, and Air. Naranja or Pina – a group activity for 6-40 participants, provides an icebreaker as a social learning activity also known as dinámicas for familiarity of names that included a designated leader that would introduce themselves with each person stating his/her/their+ name.16 Then the leader points to the person within the group circle stating the name to the left pina or right Naranja. If the person is unable to identify the name, they become the leader and move to the middle of the circle. Sea, Land, and Air helped to engage group participation, including 3-30 individuals in a circle with a ball, identifying a specific animal on the Sea, Land, or Air for the continent of the leader’s choice. If the participant is unable to identify a specific animal, he/she/they/+ becomes the leader. The introductory educational technique enabled better communication, encouraged collaboration, and engagement of all participants.

The PDSA cycle 2 occurred on January 25th, 2023 (up to 35 participants) that was modified to on-line training of the three sessions over one day due to CHSEs’ expression of childcare difficulty, and transportation. The course refined key concepts including detailed menstrual cup handouts, instructional video, menstrual cup and health brochure and provided 50 donated menstrual cups to CHSEs for distribution among clients.

The following were done in both the first and second PDSA cycle. All menstrual health training sessions involved the culturally informed interactive popular education case study and interactive learning games. The popular education strives to use familiar social engagement for introduction. All 3 case studies included familiar learning tools that took place in a collaborative approach to the adult learner setting allowing for individual and group participation. Each case study involved a subject to learn further health informed care such as avoiding menstrual taboo conversations or implementing gender affirming responses. Interactive learning games were developed from learned session material using Kahoot. The Kahoot had several benefits including online adult repetition for learning conceptualization and memory. Games were presented in both multiple choice, and true or false questions. Lastly, at the final PDSA cycle, a $10 gift card was awarded to the winner of the session as an incentive.

Project effectiveness was measured using questionnaires designed by the DNP student scholar with the academic-community project partnership review that included nursing faculty experts and immigrant and refugee community health experts. The questions were developed with mock survey presentations and refined with the team partnership addressing ease of use consisting of questionnaire scores or fill in the blank. The self-administered anonymous questionnaires were collected over two PDSA cycles with 54 participants, 25 short-term questionnaires, and 14 long-term questionnaires were returned by CHSEs and analyzed by the DNP student scholar. The short-term questionnaire data was collected at the end of each training in the two PDSA cycles and one long-term questionnaire occurred mid-February. The questionnaires’ assessed participant’s level of knowledge, comfort, and confidence in using gender-affirming language regarding menstrual hygiene and ability to teach clients. CHSEs were able to distribute the donated menstrual cups and utilized the menstrual health education. Also, the questionnaire provided CHSEs with an opportunity for feedback on education and likeliness in future work.

The project aimed to increase knowledge, comfort, and training satisfaction were evaluated via pre- and post- menstrual health questionnaires, using 11 response-type and 3 open-ended items. The data results were organized in a secure university data storage platform and reported as descriptive statistics. Overall, the CHSEs were able to achieve verbalization of increased knowledge with demonstrated ability in recall of menstrual health hygiene practices. The barriers to community immigrant and refugees can be addressed by developing buy in for the topic utilizing the team partnership integrated meetings to build leaders and learners of menstrual hygiene practices and utilizing lessons of mock scenarios addressed in case studies for health education topics. The overall integration of the menstrual health sessions was adopted with guidance of Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory where many leaders and adopters of change immerged. The training was adopted and modified based on CHSEs’ needs who were often refugees themselves, and the teachings were utilized around adoption of the facility learning styles. Implementation and adoption of practices such as case studies and popular education style along with introduction of Kahoot allowed for integrated learning and better overall outcomes. The overall goal was reached resulting in a change in knowledge, comfort, and confidence in the CHSEs at 85.7%.

The short-term project aims included 100% of invited CHSEs attended at least 2 sessions and reported 80% increase of knowledge growth; in the long-term, CHSEs incorporated the knowledge learned working with IRCO clients and reported confidence with subsequent menstrual hygiene health conversations. Overall, 39 CHSE participated in the pre- and post- training questionnaires. Post training scores showed increases of knowledge (96% in at least 3 categories) and confidence (100%) with increased capacity to provide menstrual health hygiene teaching, products, handouts, and guidance based on appropriate assessments. Long-term evaluation included successfully providing 50 donated menstrual cups distributed to CHSEs, opportunities for CHSEs to use training, teaching, and number of referrals to specialties. The success of the project was also apparent with CHSEs requesting a designed menstrual health brochure tailored to training clients and all menstruators. The results showed 92.3% overall positive comments about the menstrual health education and included expressed enthusiasm for teaching menstrual health to all genders. Overall, 85.7% of people agreed they would use the information learned in this project for future work and found the education valuable.

Moving forward, the CHSEs will be empowered to use several teaching tools and interactive techniques. The 35 CHSEs mostly had a refugee background with great insight into the need of project building and implementation. The project partnership was assembled and engaged 2 to 3 community leaders who were directly involved with clients. The process of identifying community leaders was vital and building buy in helped with clients’ adoption of the process or early and late majority per Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory. The repetition and adaption to overall techniques of CHSEs learning for a culturally integrated community helped solidify key concepts and conceptualization of important menstrual health topics.

CHSEs noted subjective feedback of feeling heard and listened to for their concerns during the sessions. Many cited economic barriers such as transportation or childcare and the ability to form adaptability and create equal learning pathways allowed for better knowledge and confidence outcomes. Several CHSEs were able to join on zoom and participate in the study steps with review of case study questions. The option for group learning and individual case study learning resulted in collaborative growth further emphasizing Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory and collaborative conceptualization. In response to requests for teaching tools and handouts, these were modified and designed with and for CHSEs and family guidance. Overall flexibility and accommodation were considered in all aspects of the learning topics that vastly contributed to better outcomes of increased knowledge and confidence.

Also addressing the topic of menstrual health within an immigrant and refugee setting allowed some women to be recognized as leaders and that may differ from how being viewed in their traditional culture. Women were encouraged to overcome taboos and discuss the need for educating all children. The delivery of the menstrual health training sessions gave many women tools to discuss the previously viewed taboo subject as a gateway to transform period poverty and educational deficits.

There were some limitations in the overall project. There was a 3-month interval between the 2 PDSA cycles due to management of schedules among the DNP Student Scholar and sessions with CHSEs. There was the nature of new leadership transitions, including new leadership within the community-based non-profit organization that may have limited integration of learning in the train the trainer format. While we were cognizant of the diverse adult learners, many CHSEs often had English as a second language and health literacy consideration can continue to be assessed in a holistic way. Another limitation included difficulty with technology application via an internet to a smart mobile phone or electronic device that was needed for the interactive Kahoot learning and questionnaire delivery.

Implications for programming and health and service practice can be expanded for a larger scale such as through the train the trainer format. This may increase the participation of diverse gender and provide leadership in action opportunities through a longitudinal approach. This can provide the timeframe, for example, for earlier identification of those who are in the laggers category and provide guidance and determine the frequency of reviews of the menstrual health training content. We recommend building upon where can track the extent of reach of CHSEs or leaders in the field such as to culturally diverse family or household clients and to also learn from clients about their experiences and perceptions about culturally inclusive and gender sensitive menstrual health education. This may help to further advance understanding of unique needs among different cultural/racial-ethnic communities and geographical areas and make improvements to address. Sustainability of efforts included recorded content education and encouragement to provide the menstrual cup and health brochure to all refugee families upon agency admission. This may mean changing in part a system infrastructure to support programming expansion for wide reach.

There are financial implications for consideration in the context of period poverty. The tangible benefits and intangible benefits of the project show a long-term benefit and savings for menstruators especially with early intervention for bleeding disorders and use of the menstrual cup. Cost includes labor: leader (15.75 dollars per hour) and 3 sessions (1 hour and 15 minutes each) totaling approximately 55 dollars annually per employee. Cost saving tangible benefits of 12,000 dollars/per menstruator with cup use and early identification of gynecological concerns for long term positive health effects. Intangible benefits include relief of stress and familiarity of menstruation, including knowledge of the Menstrual Dignity Act and relief of burden/reducing missed school days among children. Therefore, the projected benefits outweigh the minimal cost especially as the menstrual cups were donated to IRCO. We recommend consideration of finances regarding the menstrual cups for scaling to reach more cultural/racial-ethnic communities from a population health lens. This may include expanding the partnership, for example with the business not-for-profit sector and department of public health sector.

The addition of menstrual health trainings with popular education, familiar teaching styles, and interactive education increased CHSEs’ knowledge, comfort, and confidence with menstrual health teaching. CHSEs were taught additional tools for guidance including PMDD online app and CDC tools for gynecological referral. Sustainability efforts included recorded content education and encouragement to provide menstrual cup and health brochure to all refugee families upon agency admission to facilitate further discussion.

The following are individual contributions from authors who have contributed substantially to the work reported: conceptualization by CH (lead), FK (support), CKYN-T (support), and RH (support); data curation, FK (lead); formal analysis, CH (lead), FK (support), CKYN-T (support), and RH (support); funding acquisition, CKYN-T (lead); investigation, CH (lead), FK (support), CKYN-T (support), and RH (support); methodology, CH (lead), FK (support), CKYN-T (support), and RH (support); project administration, CH (lead), FK (lead), CKYN-T (support), and RH (support); resources, CH (lead), FK (support), CKYN-T (support); supervision, FK (lead) and RH (lead); validation, CH (lead), FK (support), CKYN-T (support), and RH (support); visualization, CH (lead) and CKYN-T (lead); writing – original draft, CH (lead); and writing – review & editing, CKYN-T (lead), CH (lead), RH (support), and FK (support).

The authors are appreciative of the following funding that supported in part the scholarly project dissemination: Washington State University Vancouver Nursing Faculty Development Fund (Dr. Connie KY Nguyen-Truong received). The authors are appreciative with gratitude for the contributions of Win Kyin, MB, BS, MPH, CCHW, Health Services Manager, Josephine Davie, Kahoot Technical Support, and Sokho Eath, JD, Director at the Pacific Islander & Asian Family Center of the Immigrant & Refugee Community Organization. The authors appreciate Dr. Kandy Robertson, PhD, Scholarly Professor and Coordinator, at the Washington State University Vancouver Writing Center for editing assistance on an earlier version. The authors are also appreciative of the anonymous peer reviewers and HPHR Journal Editorial Team for assistance.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Dr. Cassie Hummel (she/her) is an Alum of Washington State University, College of Nursing in Vancouver, and currently practicing as a family health practitioner serving the Native Tribal communities. She has been recognized by the Western Institute of Nursing for addressing menstrual health outcome health disparities. She has achieved and maintains application in the Sigma Delta Chi Chapter-at- Large, Washington State Nurses’ Associates, American Nurses Association, and Western Institute of Nursing. Dr. Hummel has a passion for holistic care, serving underserved communities, addressing health disparities, and improving health outcomes. Dr. Hummel received a Doctor of Nursing Practice and Family Nurse Practitioner degree.

Francis Kham is the Health Services Coordinator-3, including in the role as the Community Health Worker Coordinator at the time of the menstrual health scholarly project at the Immigrant & Refugee Community Organization and Pacific Islander & Asian Family Center.

Dr. Connie K Y Nguyen-Truong (she/her/they) is a tenured Associate Professor at Washington State University, Department of Nursing and Systems Science, College of Nursing in Vancouver. She is recognized as a Martin Luther King Jr. Community, Equity, and Social Justice Faculty Honoree. She is a Fellow of the National League for Nursing Academy of Nursing Education, American Academy of Nursing, and Coalition of Communities of Color Leaders Bridge – Asian Pacific Islander Community Leadership Institute. Her program of research is cross-sectoral and multidisciplinary, and with community and health organizations and leaders, community health workers, student scholars, and scientists. Areas include health promotion and health equity, culturally specific data and disaggregated; immigrants, refugees, and marginalized communities; community-based participatory/action research and community-engaged research; parent/caregiver leadership, disability leadership justice, and early learning; diversity and inclusion in health-assistive and technology research including adoption; cancer control and prevention, and anti-racism. Dr. Nguyen-Truong received her PhD in Nursing, including health disparities and education, and completed a Post-Doctoral Fellowship in the Individual and Family Symptom Management Center at Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing.

Dr. Renee Hoeksel is a Professor Emeritus at Washington State University, College of Nursing in Vancouver. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing, the National League for Nursing Academy for Nursing Education, and a Pro Tem member of the Washington State Board of Nursing. Dr. Hoeksel received her PhD in Nursing at the Oregon Health and Sciences University in Portland, Oregon.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.