Lin L, Ruggieri D. A Framework for public health crisis: How America has used public health to justify exclusionary immigration laws (and where we go from here). HPHR. 2022;37. 10.54111/0001/KK4

Over 1.6 million non-citizens have been expelled from America’s land borders between March 2020 and January 2022 under Title 42. For 22 years between 1988-2010, HIV-positive immigrants were deemed ineligible and had their applications for immigration denied after their immigrant medical exam. In the face of public health challenges, America has historically decided to enact strict immigration laws and used the protection of public health as the justification of such exclusionary practices. These laws, however, are often enforced without serving a true public health need. Further, they remain stagnant as they fail to be amended with new research or medical advancement.

Using 1963-2020 immigration applicant denial data from the Immigrant Visa Control and Reporting Division of the United States Department of State, we analyzed trends in immigration ineligibility. We also used data from the Department of Homeland Security to study Title 42 expulsion from 2020 to 2022. These trends were then investigated through lenses of significant policies and Presidential administration.

Policies and presidential administrations have an impact on the immigration denials and approvals. Looking at communicable diseases, required vaccination, and Title 42 we can see how trends over lay with policy and administration.

We developed a framework based on prevention, transmissibility, and severity characteristics of future communicable disease crises. The framework and policy recommendations will help create a more ethical and public health informed immigration response to crises, allowing for law and policy to change as new developments are made in science and medicine.

In times of public health crises driven by communicable and infectious diseases, immigration policies are frequently enforced as a means of controlling the spread of disease, as we showed with HIV and COVID-19. Acknowledging this history and the impact of health justified immigration policy will make America more prepared to tackle the next public health crisis.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. in March 2020, over 1.6 million migrants at the Mexican border have been expelled under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Title 42 regulation, which permits refusal of non-citizens to protect public health.1,2 Though the agency initially refused to implement Title 42 during COVID due to a lack of “valid public health reason,” CDC officials eventually bowed to political pressure from the Trump administration. While Title 42 expulsions publicly were implemented to protect the public from “serious danger of the introduction of” COVID-19,”3,4 most individuals expelled were asylum seekers. Yet the Title 42’s does not represent the first time public health measures have been leveraged to justify restrictive immigration policies in the U.S.

Immigrants historically been stigmatized as disease carriers.5 The Immigrant Act of 1882 introduced Federal health-related grounds of ineligibility (HRGIs) to limit immigration.6 At first, Public Health Service officers conducted medical inspections upon entry at locations like Ellis Island.7 Today, U.S. Civil Surgeons and foreign Panel Physicians conduct medical exams before immigration approval. At the turn of last century, a diagnosis of tuberculosis and other diseases could result in immediate deportation, while from 1987 to 2009, HIV was classified as a communicable disease by the CDC. Persons with HIV were barred from the U.S., preventing HIV research and advocacy from occurring in the U.S.8 During that time, SARS, MERS, and H1N1 also become HRGIs.9,10 Most recently, in 2021 COVID-19 vaccination became a requirement for both travel and immigrant visas.

In each case, regulations meant to safeguard the country’s public health were informed by discrimination rather than evidence, codifying fear and hate.5,11,12 Furthermore, these policies, most recently those around HIV immigration bans and COVID-19 Title 42 expulsions, provided precedence to justify future public health-justified immigration policies.

All immigrants are required to take a medical exam to demonstrate their health eligibility.13 Currently, they can be deemed inadmissible under sixty-seven grounds for refusal under the Immigration and Nationality Act, four of which are HRGIs.14,15 These HRGIs include testing positive for designated communicable or quarantinable diseases, lacking required vaccinations, having a physical or mental disability, or having a substance use disorder.16 Some immigrants may qualify for a waiver if denied for specific HRGIs. These health-related immigration policies often create fear among U.S. immigrants and can impact their health outcomes.17 Although a few articles have reviewed the development and impact of America’s HIV bans, no study has analyzed annual HRGIs data trends or explored its connection to health justified immigration policies for the current COVID-19 pandemic expulsions.18,19

Our work addresses gaps in the literature on HRGIs, specifically of communicable and quarantinable diseases. Using HIV immigration ineligibility and Title 42 in COVID-19 as case studies, this project seeks to improve understanding of how health-related immigration policies are created. This data abstraction may help us not only to understand how public health-based immigration policy has been shaped, but also how it is currently being applied in the COVID-19 pandemic, and how it may continue to shape immigration policies in future public health crises.

The primary statistical data used in this project are the 1963-2020 immigration applicant ineligibility data from the Immigrant Visa Control and Reporting Division of the U.S. Department of State. The data included the number of immigrants excluded for HRGIs and the total number of ineligibilities found each year amongst all 60+ reasons for ineligibility over the 57 year period. We used the Yearbooks of Immigration Statistics from the Department of Homeland Security for statistics on annual immigrant visas granted and collected data from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection for statistics on Title 42 enforcements from March 2020 to January 2022. To contextualize our data, we conducted grey literature searches relevant to historical immigration policy, HIV, Title 42 expulsions, among other relevant policies.

We graphed ineligibility data and analyzed them by presidential administrations and immigration policy changes. We also individually evaluated HRGIs as a proportion of the number of immigration applications reviewed that year. The number of application reviews was calculated by combining the total number of visa approvals with the number of ineligibilities determined each year. Trends were analyzed by yearly percentages for HRGIs and by monthly counts for Title 42 Expulsions. (See Table 1 and 2 for immigration policies relevant to HIV and COVID-19).

We created policy recommendations and developed a framework for future public health-justified immigration policies. Variables were selected and examples from past public health crises were used to demonstrate possibilities for future public health response.

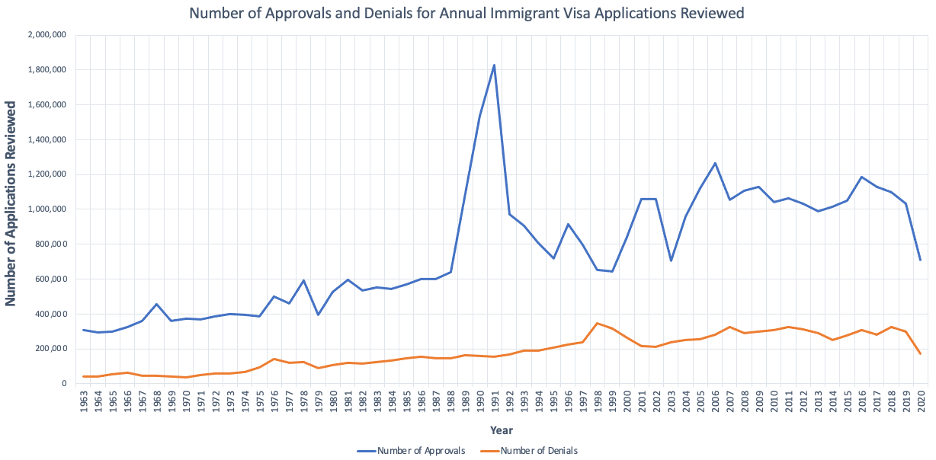

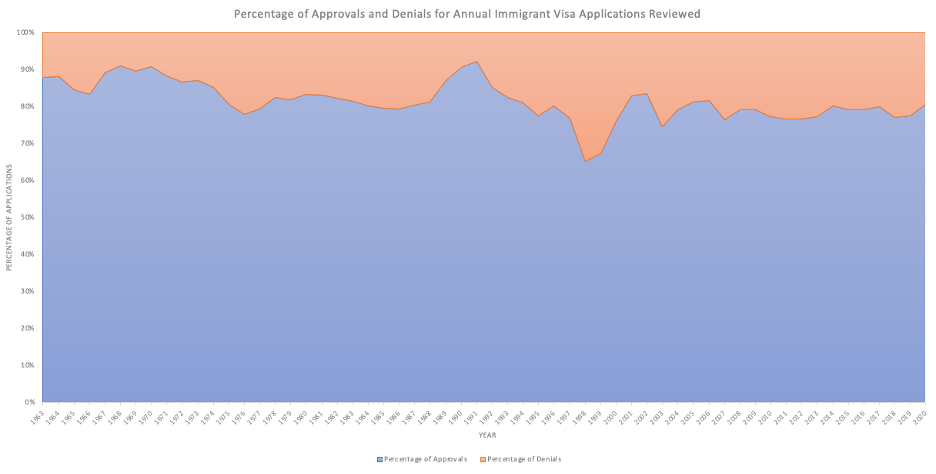

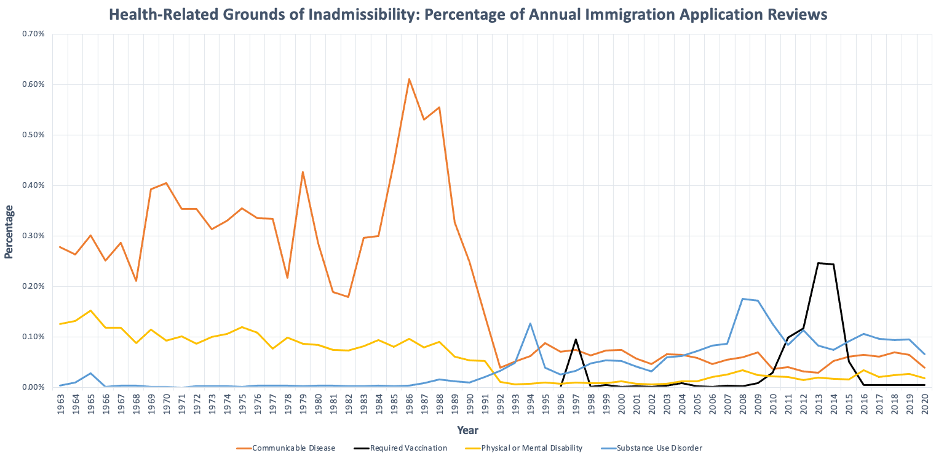

We analyzed the four HRGIs and used percentages to control for changes in the number of immigration applications reviewed each year (See Figures 1 and 2 for annual reviews, approvals, and denials). These HRGIs make up a small proportion of the total number of applications reviewed (see Figure 3 of all HRGIs). Each year, 8.88% to 34.67% (median=19.21%) of immigrant applications reviewed were denied immigration status approval for one of the 60+ ineligibilities. Between 0.34% and 5.4% (median=1.62%) of the total ineligibles were due to health-related reasons. In the graphs mentioned below, red shading represents a Republican President and blue shading represents a Democratic President.

Graph 1. Number Approvals and Denials for Annual Immigrant Visa Applications Reviewed

Graph 2. Percentage of Approvals and Denials for Annual Immigrant Visa Applications Reviewed

Graph 3. Health-Related Grounds of Inadmissibility: Percentage of Annual Immigration Application Reviews

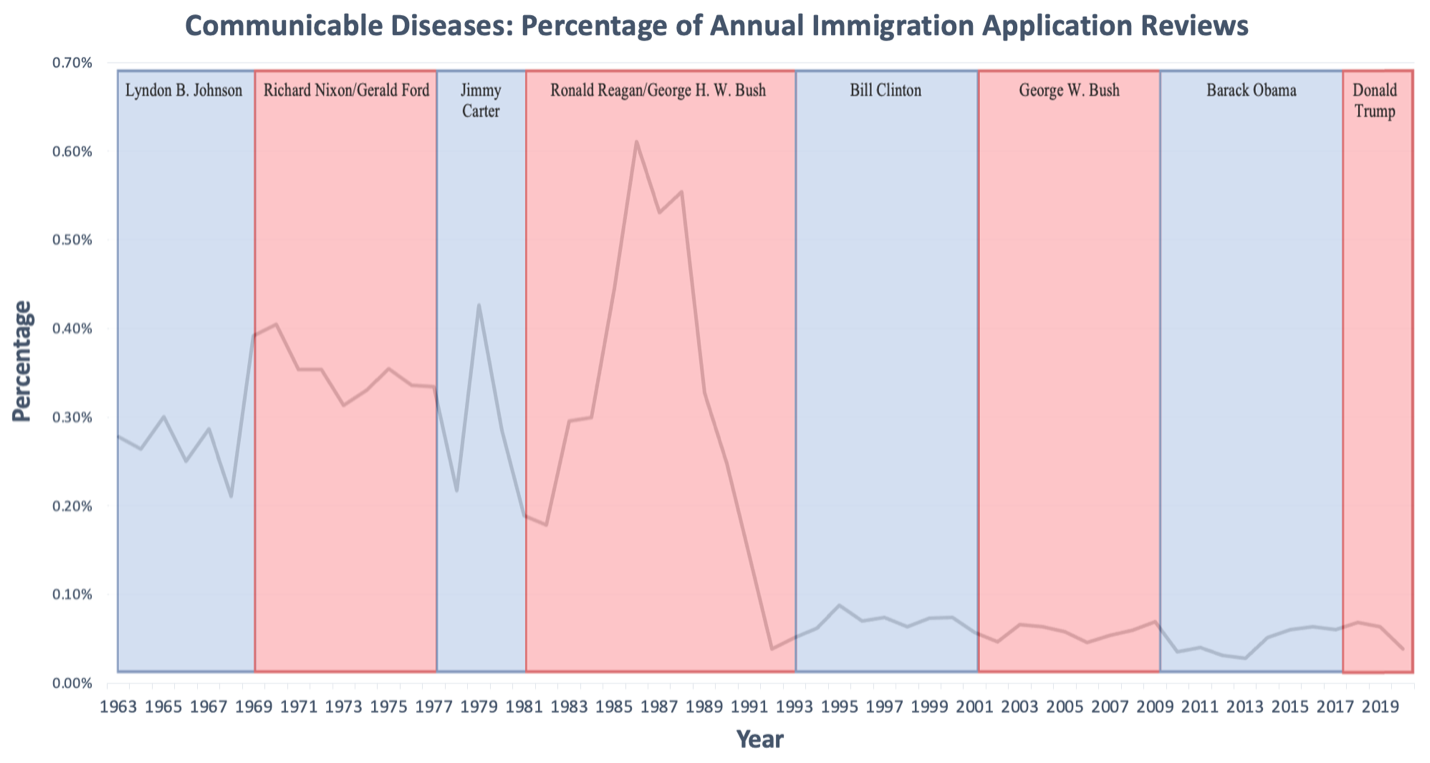

Denials for a communicable disease of public health significance ranged from 0.03% to 0.61% a year (median=.12%) (Figure 4). Between 1963 and 1981, there was no linear trend in ineligibilities, fluctuating between 0.21% and 0.43% with spikes in 1969 and 1979 and a drop in 1981. From 1981-1992 there was the largest rise and fall. There was a dramatic rise from .18% in 1982 (1,157 immigrants) to 0.61% in 1986 (4614 immigrants). There was another drop from 1986 to 1992 when only 0.04% of immigrants (440 immigrants) were denied for communicable disease. Ever since 1992, the number of immigrants denied for a communicable disease remained below 0.10%.

Graph 4. Communicable Diseases: Percentage of Annual Immigration Application Reviews

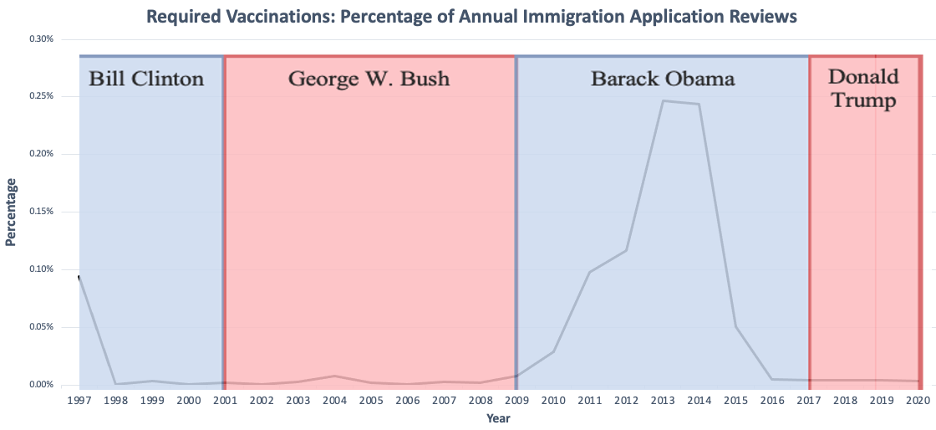

After being enacted as a HRGI in 1997, vaccination-based denials have ranged from <0.01% to 0.25% (median=0.005%) (Figure 5). The first year, 0.09% of immigrant applications were found ineligible (978 immigrants) for vaccination records. From 1998-2008 the percentage remained below 0.01% (<100 immigrants). Between 2009 and 2014, however, it rose to 0.25% (3153 immigrants) before dropping to 0.05 in 2015 (676 immigrants). It has remained below 0.01% ever since.

Graph 5. Required Vaccinations: Percentage of Annual Immigration Application Reviews

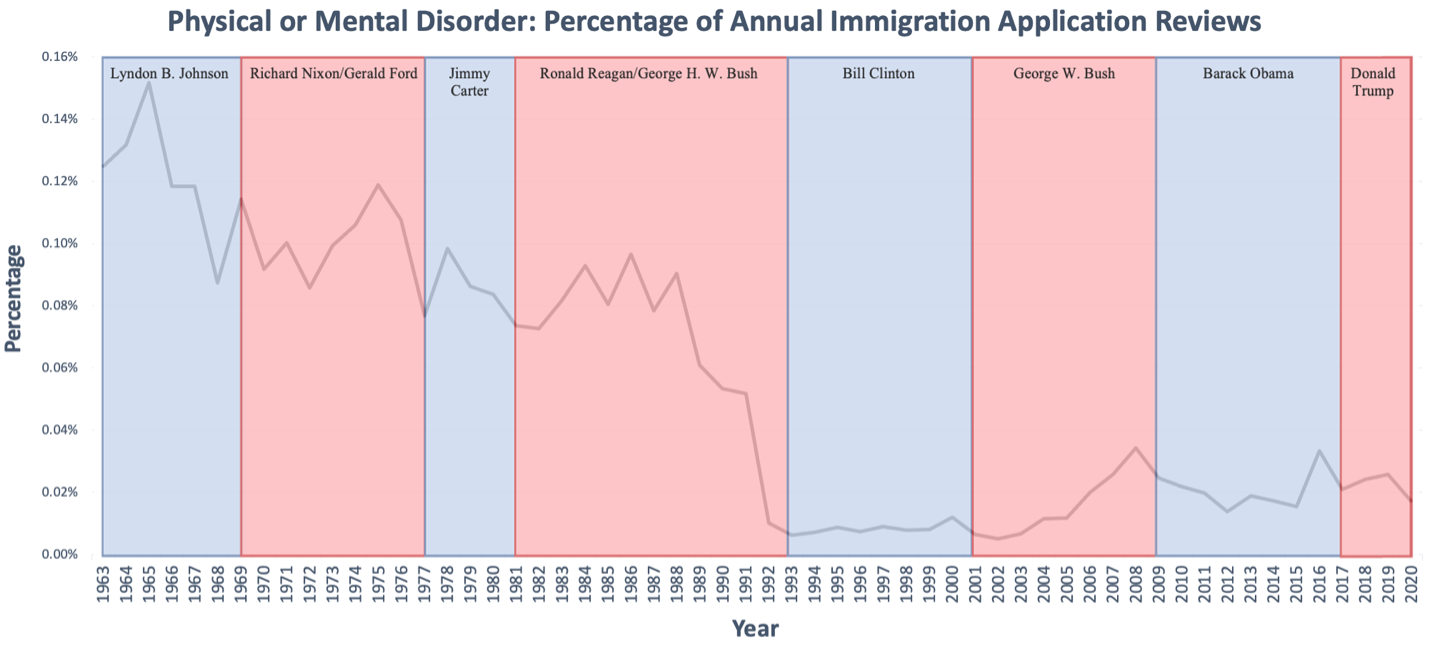

Denials based on physical or mental disabilities ranged from <0.01% to 0.15% of the annual number of application (median=.04%) (Figure 6). Since 1965 there has been a general decline in disability-based denials and dropped to 0.01% (114 immigrants) in 1992. While there was a small rise in denials between 2006 and 2020, it has stayed at or below 0.04% for the last 30 years.

Graph 6. Physical or Mental Disorder: Percentage of Annual Immigration Application Reviews

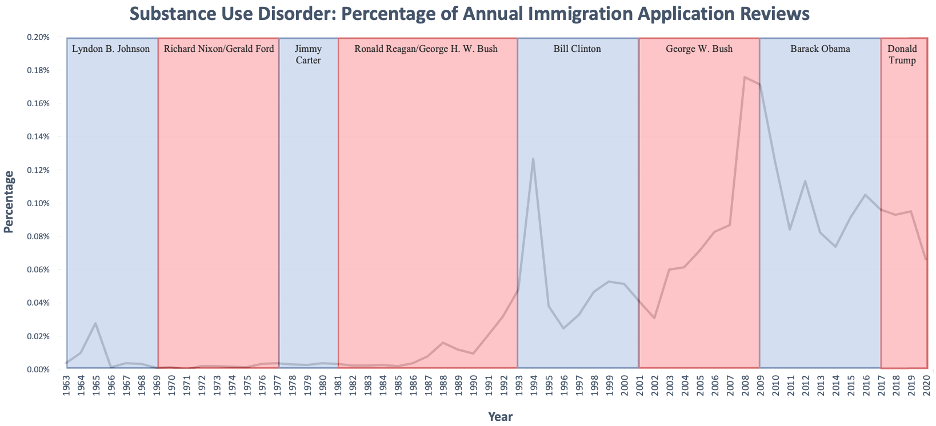

The percentage of people denied due to a substance use disorder has ranged from <0.01% to 0.18%, (median=.03%) (Figure 7). The percentage of denials largely stayed below 0.01% (<100 immigrants) between 1963 and 1987. However, from 1988 on there has been a general rise from 0.02% to 0.07% (125 to 579) in 2020, with spikes in 1994 at 0.13% (1256) and in 2008 at 0.18% (2457).

Graph 7. Substance Use Disorder: Percentage of Annual Immigration Application Reviews

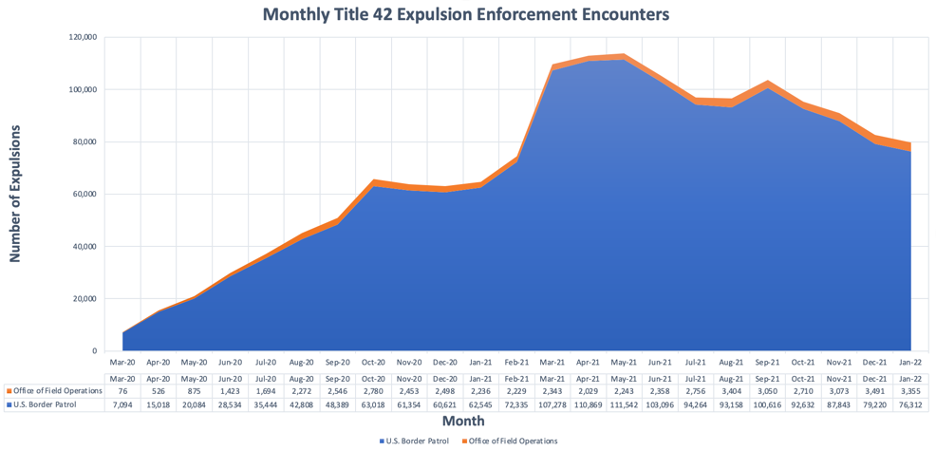

Between March 2020 and January 2022, U.S. Customs and Border Protections (USCBP) carried out 1,626,474 Title 42 expulsions. As of February 2022, migrants and asylum seekers can be expelled by the U.S. Border Patrol (96.89%) or in an USCBP Office of Field Operations (3.11%). Title 42 expulsions increased from March 2020 until May 2021, after which they began a gradual decline (Figure 8). Under the Trump Administration from March 2020 to late January 2021, 464,288 people were expelled. Under the Biden Administration, 1,162,206 people have been expelled. Different socio-political circumstances both in the United States and in other countries immigrants are coming from, have led to changes in immigration flow. We have also seen an increase in migrants from Haiti and other Central American and African nations since January 2021. For example, in May 2021, the number of undocumented migrant encounters at the Southern border hit its highest peak since April 2000, two decades earlier. While monthly expulsions and enforcements are now on the decline, every month since March 2021 USCBP has consistently had more encounters (peaking at 213,593 encounters in July 2021) than any month under the Trump administration (which peaked at 144,116 encounters in May 2019). 20,21 This can potentially indicate a perception that the Biden administration has more favorable immigration policies as compared to the years under the Trump administration, which leads to more migrants and is a sign of that there were other factors association with migration.

Graph 8. Monthly Title 42 Expulsion Enforcement Encounters

In 1987, President Reagan pressured the Public Health Service (PHS) to add HIV to the list of dangerous and contagious diseases, barred HIV-positive immigrants from establishing legal permanent resident status, and prevented HIV-positive visitors from entering the U.S.22 PHS officials pushed back against the proposed measure, citing the lack of public health threat: “AIDS is not spread by casual contact, which is the usual public concept of contagious.”23 In July 1987, Congress passed the Helms AIDS Amendments and legislatively added HIV to the ineligibility list. While the PHS had already added HIV to the list of deniable communicable diseases and maintains the full list of ineligibilities, in the coming two decades, it was argued that only Congress could authorize the removal of HIV. The ban made international news and led to a global boycott against the 1990 International Conference on AIDS in San Francisco. The IAS wasn’t hosted in the US until 2012, after the HIV ban was ended in 2010. 23

The HIV travel and immigration ban was cemented into law through the National Institutes of Health Reauthorization Act of 1993 via the Nichols Amendment. Senator Nichols argued that removing the ban “would have contributed to the spread of a deadly disease … and cost hundreds of millions of dollars at a time when we are already struggling to contain health care costs.”24 The law also removed the “suspension of deportation” clause. As a result, non-citizen immigrants were required to prove that both they and a family member would experience hardship to prevent a deportation. This especially affected LGBTQ+ HIV-positive individuals because the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act mandated that non-citizens could not claim domestic partners and same sex spouses for legal immigration purposes. (See Table 1 for a timeline of select relevant HIV immigration ban policies).

During the HIV epidemic that started in the 1980s, there was a rise and drop in the number of communicable disease denials. Interestingly, the peak was in 1986, two years before the enactment of the HIV ban in 1988. In 1992, the number of communicable disease denials fell to its lowest in this study’s timeframe, the year before the HIV ban was codified into law by Congress. Between 1982 and 1988, when there was not a HIV ban instituted, the rise in communicable disease denials could have been due to TB ineligibilities because as HIV spread, there was a strain of active TB that impacted HIV-positive individuals more than others. The comorbidity further targets gay and persons of color where HIV and TB were endemic. Communicable disease denials remained level below 0.10% during the 22-year HIV ban, this lower overall number does should not be overlook as the lower-income, LGBTQ+, communities of color are the ones disparately represented. This does not mean that people with HIV were not denied, but rather likely means that immigrants who were HIV-positive decided not to apply for immigration, knowing they would be denied. In fact, previous research has established that immigrants in the U.S. and other countries feared deportation if they tested positive for HIV.25–27 The criminalization and stigmatization of HIV functionally contributes to legalized homophobia and racism. Our results showing low application denials support this theory that fear could have contributed to fewer applications for citizenship. Research on the HIV ban related to refugees has similarly assessed that the ban disproportionally impacted non-white immigrants from underdeveloped countries.28 While there were periodic attempts to revoke the HIV immigration ban, it remained in place for 22 years until January 4th, 2010. There were no changes to the policy even after research demonstrated that HIV could not be transmitted through casual contact or following the introduction of successful HIV antiretroviral therapy treatments.

Table 1. Timeline of Select Relevant HIV Immigration Ban Policies and History42–44

Timeline of Select Relevant HIV Immigration Ban Policies and History | |

April 23, 1986 | HHS Secretary Otis Bowen proposed that the PHS add AIDS to the list of dangerous contagious diseases. |

June 8, 1987

| HHS published a proposal to include AIDS as a dangerous contagious disease. |

July 11, 1987

| Congress added HIV to the list of Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) specified contagious diseases. |

August 28, 1987 | HHS issued final regulations to include HIV in the list of communicable diseases of public health significance. |

January 23, 1991 | The CDC published a proposed rule to remove all diseases from the list of communicable diseases, including HIV infection, except for infectious tuberculosis. The public comment period opened. |

May 31, 1991 | After comments and protests from those like the Republican Party in Congress, the HHS published an interim final rule keeping the list, including HIV. |

1992 | Presidential candidate Bill Clinton promised to remove the HIV ban if elected. |

June 8, 1993 | After 20 months of detention, Federal Judge Sterling Johnson Jr, ordered Attorney General Janet Reno to immediately release 158 Haitian Refugees detained at an “HIV Prison Camp” at Guantanamo Bay. |

June 10, 1993 | Congress amended the INA to include “infection with the etiologic agent for acquired immune deficiency syndrome” as a communicable disease of public health significance. This legislatively made HIV a grounds for ineligibility. With veto-proof majorities in Congress, President Clinton signed the bill into law. |

July 30, 2008 | Congress amended the INA and removed “which shall include… infection with the etiologic agent for acquired immune deficiency syndrome.” The Secretary of HHS now was authorized to decide HIV should be a communicable disease of public health significance. |

July 2, 2009 | The CDC published a Notice of Proposed Rule Making to removal HIV infection from list of communicable disease of public health significance and to remove the requirement for medical exams to test for HIV. |

January 4, 2010 | HIV is officially removed from the list of communicable diseases of public health significance. |

As the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, the World Health Organization “advise[d] against the application of travel or trade restrictions to countries experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks.”29 However, the U.S. and other countries enacted travel restrictions, including Title 42 of the Public Health Service Act on March 20, 2020. The order halted all asylum processing at the U.S. land borders of Mexico and Canada, stripping individuals of their right to asylum. The order was justified to limit spread of COVID-19 in detention centers, however, no alternatives to expulsion, such as expedited processing or community-based management to protect public health, were implemented.

Title 42, like the HIV immigration ban, faced tremendous pushback and allowed the Trump Administration to weaponize COVID-19 to support racist immigration policies. CDC officials initially refused the Trump administration’s directive due to the lack of public health evidence. Ultimately, Vice President Pence called CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield,28 who used his emergency powers to issue Title 42 Expulsion ostensibly to stop the “introduction” of persons from “Coronavirus Impacted Areas.” This gave Custom and Border Patrol the ability to expel non-citizens arriving at the border. Citizens and other lawfully permanent residents were not barred from entry into the United States even if they were coming from “Coronavirus impacted areas.” Former CDC officials claimed, “they forced us…it is either do it or get fired.”30 (See Table 2 for a timeline of select relevant Title 42 enforcement)

Recently published research on Title 42, detailed the negative impact that Title 42 and other policies like the Remain in Mexico Policy had on asylum seekers, particularly those at Matamoros refugee camp. They too support the notion of potential weaponization of COVID-19 to advance political motives within the asylum system. Title 42 has had a direct impact on the number of Customs and Border Protection apprehensions—as more people were expelled, the number of people entering detention plummeted.31 Together, our studies showcase the impact that Title 42 public-health driven immigration policies can have and the need for further research.

Title 42 has face continued opposition on public health grounds. In May 2020, 57 public health experts wrote a letter to the Trump administration asking for the order to be revoked, stating it “fails to protect public health” and that “there is no public health rationale for denying admission to individuals based on legal status.” 32 Immigration and COVID-19 continues to be a politicized issue today. Most recently in October 2021, a Kaiser Family Foundation Poll found that 55% of Republicans and 40% of unvaccinated U.S. adults believe that immigrants are a major reason for America’s surge in COVID-19 cases during the Delta Variant Wave. Dr. Anthony Fauci responded to the polling by saying “the problem is within our own country. Certainly immigrants can get infected, but they’re not the driving force of this. Let’s face reality here.”33 And in relation to Title 42 he said, “My feeling has always been that focusing on immigrants, expelling them…is not the solution to an outbreak.”

While many hoped Biden would revoke Title 42, the administration has continued its enforcement. Court decisions have since allowed unaccompanied minors to enter, but all others have been expelled. Rather than implement alternative options, the Biden administration has reaffirmed Title 42’s validity as public health policy and more migrants have been expelled under Biden than have under Trump. On February 4th, after its third 60-day review, the CDC decided to maintain Title 42 cementing its use for at least two years. 34 This along with the recent short-lived travel bans enforced on Southern African nations during the start of the Omicron variant wave of COVID-19 further exemplify the need for better evidence-based immigration and travel policies over reactionary policies. 35

Table 2 Timeline of Select Relevant Title 42 Enforcement Policies and COVID-19 History45–48

Timeline of Select Relevant HIV Immigration Ban Policies and History | |

July 1, 1944 | Title 42 is codified into law in the 1944 Public Health Service Act. |

March 20, 2020, | Department of Health and Human Services issued an emergency interim regulation of Section 265 of U.S. Code Title 42. This code allowed the CDC Director to “prohibit the introduction” of people into the U.S. if “there is serious danger of the introduction of [a communicable] disease into the United States.” |

September 11, 2020 | HHS published the final version of the March interim regulation |

October 1, 2020 | The CDC reissued the Title 42 order to continue the expulsions. |

November 18, 2020 | Judge Emmet Sullivan rules that unaccompanied children cannot be expelled under Title 42. The U.S. government successfully appeals. |

February 2, 2021

| Even though the government won its appeal, the CDC decided to issue a notice formally exempting unaccompanied children from expulsion. |

May 20, 2021 | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees condemned America’s use of Title 42, suggesting an infringement of the right to asylum. |

August 2, 2021

| The CDC issued a new order to replace the October 2020 order. This was an indefinite extension and would be reassessed every 60 days. |

September 16, 2021

| Judge Emmet Sullivan ruled that Title 42 cannot be used to expel migrant families, and says “Section 265 simply contains no mention of the word ‘expel’ — any synonyms thereof — within its text.” The Biden administration successfully appealed the ruling. |

October 1, 2021 | COVID-19 vaccination is added to the list of required vaccinations for documented immigrants. |

October 2, 2021 December 3, 2021 February 4, 2022 | CDC completes 60 day reviews and maintains Title 42 |

While not the focus of this study, required immunization ineligibility data also showed interesting trends. Required immunizations for immigrants include mumps, measles, rubella, polio, tetanus and diphtheria toxoids, pertussis, haemophilus influenzae type B, hepatitis B, and other vaccine-preventable diseases recommended by the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices.36 Most recently, COVID-19 was added as a required immunization on October 1, 2021. The data illustrate how administrations and politics can play a role in immigration eligibility. Since 1997, the only times when denials raised above .01% of all immigration reviews were under President Clinton and President Obama. Under President Bush and President Trump, the number of denials remained below 0.01%. There was a spike at the start of Obama’s presidency and a drop at the end of his presidency. Over this time, the Advisory Committee had added vaccines. On August 1, 2008, under the Bush administration, Rotavirus, Hepatitis A, Meningococcal, Herpes Zoster, and HPV vaccinations were added as required vaccinations.37 On December 13, 2009, under the Obama administration, the Herpes Zoster and HPV vaccination requirements were removed. These new requirements likely contributed to the rise in immigrant denials during Obama’s presidency. The stark differences, like the drop in vaccine ineligibility at the end of the Obama administration and during the Trump administration warrant more investigation to see if it was motivated by politics or public health. Furthermore, while research in the EU showed that measles outbreaks were linked to migration, the work illustrates the debate around the ethicality of vaccination requirements for less transmissible non-airborne diseases, such as HPV.38,39 The data help show how an administrations’ policies, interpretation of laws, and strictness of immigration enforcement can all impact immigration.

In discussing implications of our work, it is important to first acknowledge that it is not possible to fully isolate politics from public health given the role all three branches of government play in public health law. Our recommendations are therefore focused on working to ensure that policies are informed by quality science, medical research, and public health progress.

When possible, Federal public health authorities should have the ability to assess public health conditions and issue orders without political pressure. With both HIV and COVID-19 immigration restrictions, Presidential pressure pushed for the HIV ban and Title 42, even when officials at the Public Health Service and the CDC contended that there was not enough public health justification for these policies. Granting more authority to the Department of Health and Human Services and its public health officials to review health-related immigration policies may result in better public health policy. For example, there can be independent boards within HHS that serve the purpose like the Congressional Budget Office does for Congress in reviewing and reporting the potential results of rules and policies. The board can assess and provide recommendations for these health based immigration policies. The board should have the ability to include factors like human rights and dignity to their reviews to center the human lives that are impacted by these policies.

The CDC maintains the list of communicable diseases of public health significance and should have more authority to update the list of diseases without needing Congressional permission. In the case of HIV, because it was added to the list of ineligible health conditions both legislatively and administratively, it required Congressional authority to be remove. In the early 1990s, the CDC failed in their attempt to remove HIV and other diseases from the list. In 2008, Congress finally amended the Immigration and Nationality Act which included a provision to remove AIDS from the list of ineligibilities. It was only then that the CDC had clearance to repeal the ban themselves. Therefore, the CDC should have more authority as those with the most technical knowledge in maintaining and changing the list of diseases to decrease the amount of political influence from Congress.

Immigration and refugee policies should also align with non-immigrant traveler policies – if there are general travel restrictions, immigration and asylum policies should not be more restrictive than those non-immigrant travel policies. For example, on October 1, 2021, all immigrant applicants needed to be vaccinated for COVID-19; the same policy took effect on November 8, 2021 for non-immigrant travelers. However, asylum seekers are still expelled from the country without processing due to Title 42. COVID-19 does not spread biologically differently for an asylum seeker than from a non-immigrant traveler, yet instead withdrawing the implementation of Title 42 and creating a consistent vaccine requirement across the board, asylum seekers currently face more restrictive policies than other immigrants, indicating that the policies are in place for potential political, and not solely health, reasons. There will be a time where COVID-19 is not leading to Title-42 expulsion. There will also be a time where America is faced with another public health and global health challenge.

The subsequent sections of the paper focus on how America immigration policy and law can be better tailor to respond to public health crises. However, the data and historical analysis create additional opportunities future research. Our study has consolidated and graphed HRGI data. Now other work can be done to investigate specific time periods, looking at the health conditions at those time as well as the policy conversations happening in different branches and levels of government. Examples include the vaccine requirements denials during the Obama administration, Ebola related immigration ban proposals in congress, the impact of amnesty during the Reagan administration, the role of lower international movement during COVID-19, a deeper dive into individual years of the HIV crisis, and the drop in mental and physical disability denials in the early 1990s. While these were not the focus of this study, they are important studies relevant to the intersection of immigration and public health. Additionally, the analysis of immigration law was centered on American response, and additional work can be structure around the international perspectives. America is not alone in implementing health requirements and prerequisites for immigration. To this date some countries still have HIV immigration restrictions in play. A survey of immigration policies of other countries can be done to find best practices that could be transferable. An analysis of international laws, conventions, and treatises could be done to better understand its influence on American policy or bolster arguments for ending policies like Title 42. Finally, on the international front, future research can focus on the potential for collaborative international efforts to address asylum and health issues.

Travel and immigration restrictions have been enforced or advocated for during various public health crises. Whether to protect American citizen, to calm fears, or to gain political favor, these restrictions need to be subject to ethical reflection before enforcement. There are rights that need to be upheld and ethics that should be considered. For example, under Article 14 of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights people have the right to seek asylum from persecution.40 An immigrant’s health conditions, among other moral reasons, should not subject them to unreasonable requirements and bar them from exercising their international human rights. It is under these lenses that one can understand why activists fought against the HIV immigration ban in the 1980s and how Title 42 Expulsions violate the right to asylum migrants have at the border today. These laws ultimately target and stigmatize persons and communities. The -isms and -phobias of immigration law should not undermine valid public health guidance – the ableism in American disability ineligibility, homophobia in HIV bans, anti-Latinx/Asian/Black xenophobia and racism in targeted COVID-19 restrictions, and overarching nativism surrounding all immigration policy. A country cannot ban or deport a disease. That is why the WHO advised against closing borders at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic ,and continued to assert the approach’s unsustainability months into pandemic.41 Leaders need to think about these rights and moral consideration when faced with a public health crisis. If immigration bans are inevitable even after these considerations, then leaders can leverage the following framework. We created the framework to ensure immigration restrictions evidence-based and applied only when necessary. The restrictions should end when they are no longer necessary or transition to less restrictive requirements like testing when available.

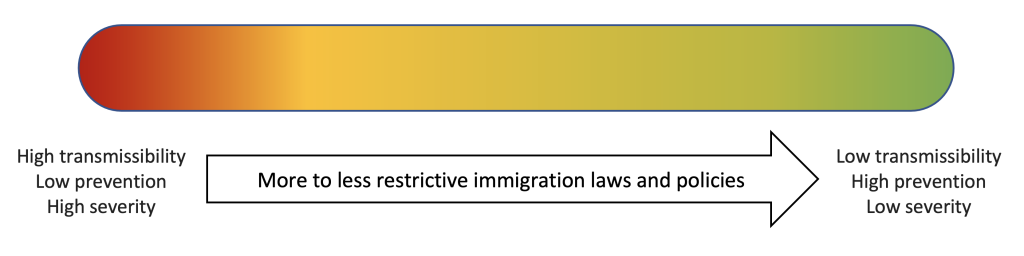

The data and discussion presented in this paper show that public health-justified restrictive immigration policies can have a direct impact on immigrant communities. American immigration response in public health crises often fit into rigid YES or NO categories: expel vs do not expel or ban vs do not ban. The HIV ban stayed unchanged for 22 years and the Title 42 Order has largely remained the same since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, when it comes to public health response, there should be a feedback loop of policy development. Policy making should follow an iterative process that responds to the scientific research, medical capacity, and characteristics of a public health crisis. To make immigration policy successful and ethical during public health crisis, we propose a framework for future response, based on lessons learned from historical policies and trends.

The following Public Health Informed Immigration Policy Framework as a way policy makers might determine how restrictive or relaxed immigration regulations should be when the country is faced with communicable diseases. Importantly, this framework allows for a spectrum of response efforts as opposed to the YES/NO dichotomies previously used by the government. Three categories of consideration for this framework are Transmissibility/Prevalence, Prevention, and Severity/Treatment, in no order of importance. Variables that can be used to determine the level of importance for each of the 3 categories are described here, but other variables of interest for specific public health crises can be added and irrelevant ones excluded. HIV, COVID-19, and other past health crises are used as examples to illustrate each variables’ use. This framework can be applied more generally regarding travel restriction considerations or more specifically with immigrant visas.

1. Transmissibility and Prevalence |

a. Mode of Transmission |

b. Basic Reproductive Number: How many people on average can one person infect? |

c. Prevalence and Incidence |

2. Prevention |

a. Testability |

b. Quarantine |

c. Vaccines |

3. Severity and Treatment |

a. Cure/Treatment/Medication |

b. Hospital/Medical Capacity |

c. Supply and Supply Chain Capacity |

Applying the framework variables to a spectrum of more restrictive to less/no restrictive immigration laws will allow for policymakers to better adapt policies to an evolving public health crisis related to communicable and infectious diseases. At the start of a communicable disease crisis, there is often little that is known about the contagion or virus. It is during these times when fears arise, and politicians may consider stricter immigration and travel restrictions. These reactions should not be driven by fear, as a quick response can lead to unintended or unethical consequences to immigrants and public health. If they are implemented, policymakers should use this framework to pull back on restrictions as new public health research and understanding is produced. These criteria in no way endorse enforcement of immigration restrictions, they only provide variables to consider in policy development.

The framework focuses on three categories of variables. Transmissibility and Prevalence encompass variables that impact how people, how many people, and how fast people are being infected. Prevention measures are critical to controlling new infectious diseases and variables include testing, quarantine, and vaccination. Finally, Severity and Treatment includes measures to determine how deadly a disease is, how treatable it is, and how prepared America is to take on the disease. (See Tables 3, 4, and 5 for the variables, explanations, and examples).

Table 3. Public Health Informed Immigration Policy Framework: Transmissibility and Prevalence49–51

| Variable | Description and examples |

Transmissibility and Prevalence | Mode of transmission | Communicable diseases can be spread through different means be it aerosols, droplets, sexually, animal vector borne, blood borne, among others. These modes of transmission may not be known at the start of an outbreak but once they are known, law should reflect the level of transmissibility. For example, air borne diseases are more likely to be spread than sexually transmitted diseases. HIV infection, a predominantly sexually transmitted illness, should not have been banned for 22 years if the justification was for public health protection given the lower likelihood of transmission. Whereas with airborne transmission diseases like COVID-19 where interpersonal transmission is more likely, it is comparatively more ethical to have restrictive policies, assuming preventative measures did not exist. |

Basic Reproductive Number | How many people on average can one person infect? This number based on infection producing contacts and the infectious period can be a guide for how transmissible a disease is. The higher the R0, the more ethical it could it is to have travel restrictions and as the R0 changes so should policies. Similarly, the higher the R0 the more ethical it is to implement immunization requirements, and when immunizations are accessible, immigration restrictions and bans should be repealed. This infectiousness should not be view in isolation, it should also be viewed with other factors like severity. Different policies may be decided when comparing a more infectious but less severe disease vs a less infectious but more server disease, as we saw with different variants during COVID-19. | |

Prevalence and Incidence | The prevalence of a disease is determined by the number of cases of the disease in the population. By considering disease prevalence, policymakers can better adjust immigration and travel restrictions. If America has a high prevalence, it would be more ethical to have travel and immigration restrictions. Whereas restrictions should be rolled back when the disease is under control and there is a lower prevalence. Furthermore, incidence rate of new cases can be considered in cases when an infection is more long lasting, like HIV, as well as with COVID-19 when data reporting modernization was accessible. |

Table 4: Public Health Informed Immigration Policy Framework: Prevention 52,53

Variable | Description and examples | |

Prevention | Testability | When tests for a disease or infection are created, it allows for a way to determine who is at risk of being a vector. Testing can be an important measure to end or avoid over encompassing immigration bans that apply to people who do not have the disease. Testing also is something that can be implemented as a pre-travel/immigration measure. For communicable diseases like COVID-19 where there is an end of the infectious period, an immigrant should be allowed to test again to show a negative test instead of being denied and forced to reapply for immigration. For viruses like HIV which are not curable, tests can be a means of informing an immigrant of their status and be a means of precaution or connection to care as opposed to a ban on immigration. |

Quarantine | For those who test positive and when a finite infectious period is known, quarantine is an option to protect public health while also not barring an immigrant all together. Instead of denying an immigration application for a positive test, quarantine or isolation can be required until a person is no longer infectious and then allow their immigration to be subsequently approved. This should not be a consideration for long-term infections where mandating long-term quarantine would violate a person’s rights. This was evident when hundreds of HIV-positive Haitians were quarantined at Guantanamo Bay for 20 months, and abuse of quarantine powers that was motivated by stigma and discrimination of Haitians at the time. | |

Vaccines | Vaccination requirements are already a part of the immigrant medical examination. If a vaccine is created for a disease, immigration bans should end and can transition to vaccination requirements. This can help protect public health and not prolong unnecessary restrictions. An immigrant should not be denied, however, due to their country’s lack of access to vaccination. Those requirements can be waived, and America should also offer vaccination to those people once they have arrived. Vaccinations should also not be burdensome and may not need to be required for less transmissible diseases like HPV that are not spread through casual contact. While that does not mean a vaccination isn’t beneficial, this requirement may be less ethical as it may not be in line with the goal of preventing highly communicable disease. |

Table 5: Public Health Informed Immigration Policy Framework: Severity and Treatment54,55

Variable | Description and examples | |

Severity and Treatment | Cure, Treatment, and Medication | Cures, treatments, and medicines are a milestone in disease and public health response. If this stage of medical progress is reached and people who are sick have a means of being cured or recovering from the infection, severity of the crisis may be markedly down, and travel restrictions should be rescinded. Treatment should also be offered to immigrants who are diagnosed with the illness so they can be cleared for immigration instead of being denied. Currently, Gonorrhea, Leprosy, and Syphilis are all communicable disease that can make an immigrant ineligible, yet treatments have been created for all three since the time they were added onto the list. These are examples of times when immigrants should be connected to treatment and these ineligibilities should be removed from the list. For certain illnesses, preventative medication may be created, like PrEP and PEP for HIV. When these medications are created, restrictions should also be relaxed. |

Hospital and Medical Capacity | COVID-19 has showcased hospital and medical capacity issues. Whether in the form of hospital staffing, bed availability, or medical equipment access, these can all play a role in America’s response to care and impact how severe a public health crisis is. If we have the capacity to care for immigrants who may become sick, then travel restrictions due to public health reasons may not be justified. Only when we are over capacity should it be ethical to use medical justifications for barring immigrants. | |

Supply and Supply Chain Capacity | Supply concerns are a broad category dealing with supplies/equipment and the means of getting those supplies for public health response. This can include masks, condoms, and even non-health related supplies. If trade is slowed, materials for production are low, or governmental stockpiles are used up, our response can be hindered and crisis severity may rise. Like hospital and medical capacity, these supply concerns may end up impacting immigration restrictions. Instead of barring immigrants during times of need, however, policies may be in place to pause visa reviews and can be reopened once capacity issues are addressed. This is important as capacity issues should not be the reason for an immigrant’s denial but rather it is more ethical to delay a review if it means the immigrant will have a honest review of their application. |

Health considerations laid out in the framework are helpful, but they also do not exist in a vacuum. It is a good guide but there are grey areas and other considerations. These following systemic and environmental considerations acknowledge other factors that impact immigration policies, though they should not be the only thing driving policy. Conditions of another country are an aspect of global health America cannot control. This includes the prevalence of a disease in a country, or the policies the country’s leaders implement. These considerations often impact immigration policies as restrictions are targeted at areas that are most at risk, for example Wuhan with COVID-19 or West Africa with Ebola. When possible, immigrants should not be categorically barred just due to their country of origin. If there are tests, for example, then tests should be administered to people from those affected countries to confirm individuals’ health status instead of a blanket ban for all people from that country. Additionally, the country selection should not be politically motivated as it has been with COVID-19, where Southern boarder migrants are getting one set of policies with Title 42 when other countries are not subject to the same policies, notable during a time with high anti-Latinx sentiment and racism.

Economic considerations are often a large debate during public health crises. Whether it be the shutting down of economies during lock down or the loss of the workforce due to sickness, leaders often look at economic impact when making policy decisions during public health crisis. While this is important, it should not supersede public health concerns and should not negatively impact the immigration process. Trade, commercial flights, and medical assistance can all be positive economic considerations to consider before travel and immigration restrictions.

Finally, politics underlie all these conditions when it comes to policy makers. Republican response to COVID-19 sentiment, re-election motivations of the 2014 midterms during Ebola, and anti-LGBTQ HIV politics are all examples of a history of politics impacting American public health response. Politicians must understand the lives that are impacted by their actions and should be held accountable for them. This paper has shown that leaders and policies impact immigration during public health crises, and while it is not possible to omit politics from public health entirely, better health informed politics is achievable.

There are also non-health factors that are not accounted for in fluctuations in immigration statistics. This includes amnesty for undocumented immigrants in the late 1980s which led to a rise in the number of immigrants in those years, push-and-pull factors of why immigrants decide to migrate, human rights violations, among other country conditions. We used percentages for ineligibility instead of pure counts of ineligibility to control for annual changes, however, it is not possible to control for every immigration factor. Secondly, communicable disease denial statistics do not specify which disease was found that led to the denials. This means we cannot know if denials were due to HIV or some other disease in the 1980s. However given the stigma and media coverage of HIV at the time, it is likely that HIV was a contributor to the denials. Third, the framework variables do not have an order of importance, so it is difficult to say if prevention measures are more important than transmissibility measures. Therefore, we did not rank the framework variables which set how restrictive policies should be and instead have kept the bar as a fluid measurement. Policymakers should consider the variables and make informed decisions themselves given the context of their public health crisis. Finally, because HRGIs and Title 42 are under different legal authorities, the generalization of the framework variables can vary. The legal authority and policies that policymakers decide to enact will all impact how immigration policy is shaped; therefore, the framework may be best used be used as a starting point. Just like how immigration policies should be flexible and dependent on the public health crisis, the applicability of the framework variables should also be flexible.

Through the analysis of Health-Related Grounds for Ineligibility, we found that policies and administrations can have an impact on the percentage of immigration denials. Our research provides policy recommendations and a framework to create public-health informed immigration policy. The compiled data also provide various opportunities for future research. By assessing variables of transmissibility, prevention, and severity, policy makers can more ethically make immigration policies that are flexible enough to change with scientific progress. In times of public health crises driven by communicable and infectious diseases, immigration policies are frequently enforced as a means of controlling the spread of disease, as we showed with HIV and COVID-19. Acknowledging this history and the impact of health justified immigration policy will make America more prepared to tackle the next public health crisis.

I would like to thank my mentors Michael Jones-Correa, PhD and Sherry Morgan, PhD, MLS, RN; the Department of State for providing the immigration data; and my Capstone classmates who helped make my capstone possible.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Louis Lin is a JD Candidate at Harvard Law School and Master of Public Health graduate from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is also the Caucus Director of the American Public Health Association’s Asian Pacific Islander Caucus. Before law school, he served as the Eviction Diversion Project Coordinator at Philadelphia Legal Assistance. His research areas are at the intersection of public health and immigration policy.

Dr. Dominique Ruggieri specializes in public health communication, education, research, and promotion. She is the Capstone Director and Core Teaching Faculty for the University of Pennsylvania’s Master of Public Health Program under the Perelman School of Medicine.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.