DiVito B, Payton C, Shanfeld G, Altshuler M, Scott K. A collaborative approach to promoting continuing care for refugees: philadelphia’s strategies and lessons learned. Harvard Public Health Review. Spring 2016;9.

Refugees arrive in the United States with medical and non-medical needs, many of which require collaborative support from multiple stakeholders. The Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative (PRHC) was developed through partnerships between resettlement agencies and health clinics to create an equitable and sustainable system to address these needs and improve resettlement success. By providing access to high-quality, community-centered health care, PRHC has successfully decreased the time to initial health screenings, connected refugees to a patient-centered medical home, and addressed complex medical needs of refugees, while improving the knowledge and capabilities of health care providers and community partners. These achievements have made the PRHC a model for providing continuing health care to newly arrived refugees, with a particular focus on those facing complex medical and social challenges.

A refugee is a person who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of their nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail him/herself of the protection of that country,” (Refugee Act of 1980; UN General Assembly, 1950). Often refugees have lived many years in refugee camps or urban environments with limited access to food, clean water, adequate shelter, and health care services. Many refugees arrive with significant medical conditions, including traumatic injuries from war, communicable diseases, and unmanaged chronic health conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Eager to begin anew but often struggling with limited English proficiency, refugees benefit from support navigating the often complex U.S. health care system. Moreover, developing capacity to interface with the health care system supports self-sufficiency among refugees, facilitates employment and school enrollment, and allows refugees to grow as individuals, families, and community-members who contribute to society.

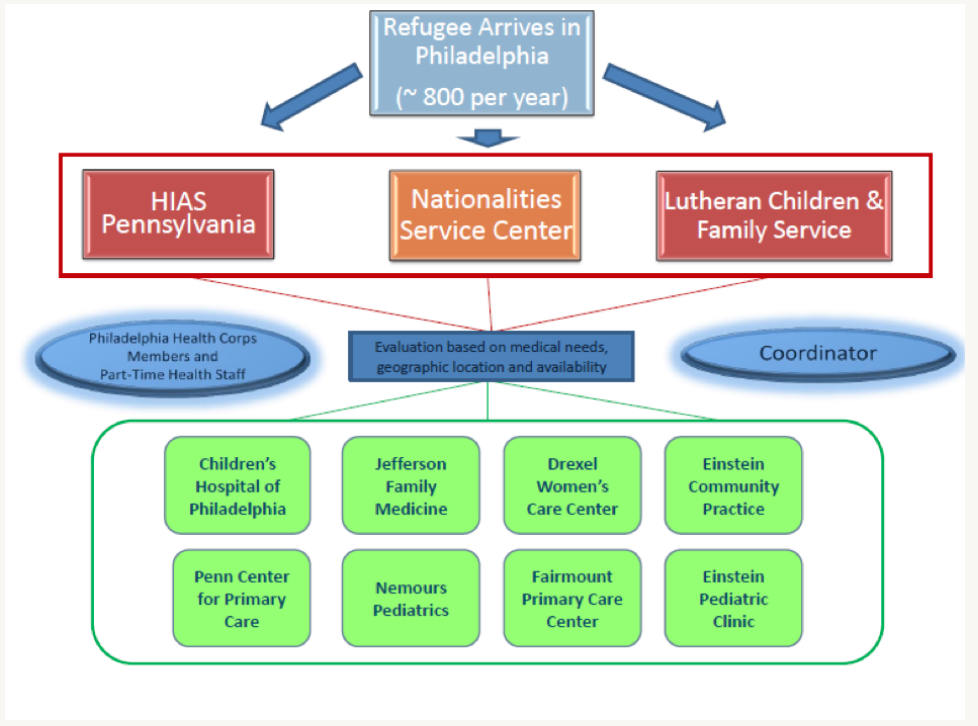

In recent years, the U.S. has accepted approximately 70,000 refugees per year, of which 2,700 settled in Pennsylvania and approximately 800 were placed in Philadelphia (Refugee Processing Center, 2015). Recently, most refugees in Philadelphia come from Bhutan, Burma (Myanmar), Iraq, Eritrea, and the Democratic Republic of Congo – a composition very similar to overall U.S. refugee population (Refugee Processing Center, 2015). In Philadelphia, refugees are resettled by one of three local non-profit resettlement agencies: Nationalities Service Center (NSC), Lutheran Children and Family Service – Southeastern Pennsylvania (LCFS), and Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society Pennsylvania (HIAS). The refugee resettlement agencies are responsible for the entire resettlement process, which includes ensuring safe and affordable housing, education, employment, health insurance, community orientation (including an orientation to the U.S. health care system), and an initial domestic health screening. When possible, resettlement agencies also support escorts to healthcare appointments.

For example, each year Nationalities Service Center (NSC) – a local affiliate of the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI) – provides educational, social, and legal services to approximately 400 refugees, as well as many other immigrants in the Philadelphia area. NSC has partnered with community health organizations to improve support for immigrants and refugees living in the Philadelphia area. Refugees with multiple medical conditions require greater coordination between health care providers and case managers working to facilitate housing, employment and education in addition to increased medical services (U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, 2015).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all refugees receive an orientation to the U.S. health care system and an initial domestic health screening within the first 30 days following arrival (CDC, 2012). Historically, resettlement agencies have created and developed their own orientation programs, while the Pennsylvania Refugee Health Program reimbursed healthcare providers for refugee health screenings based on the Participating Provider Agreements (PPAs). This model included health screenings (primarily focused on communicable diseases) for refugees and the results being reported back to the state. Several other states operate similar models that require specific providers to conduct screening appointments (CDC, 2013). Limitations to this approach include: (1) access to a limited pool of providers with an active PPA, (2) limitation of services to a specified menu of screening tests rather than more comprehensive (and longitudinal) primary and preventative care, and (3) inadequate financial support to facilitate evaluation and follow-up care for refugees with significant medical conditions (e.g., hepatitis B, latent tuberculosis, hypertension, cancer, depression).

While some states have developed state-run systems ensuring that refugees are referred to medical providers for refugee health screenings, other states – including Pennsylvania – have no established statewide screening system. In these areas, resettlement agencies assume the primary responsibility of ensuring that refugees receive screenings within 30 days of arrival. These resettlement agencies may struggle to find medical providers with adequate cultural and technical competence to provide high-quality screenings let alone follow-up care. Moreover, the standard barriers that many refugees face, including language access, accessing health insurance and navigating the U.S. healthcare system, may lead to further delays in obtaining the recommended screening within the first 30 days of arrival. Prior to the development of the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative (PRHC), none of the local resettlement agencies consistently ensured that the refugees they resettled had comprehensive orientations or timely initial domestic health screenings. Many of these agencies employed an ad-hoc system of referring refugees to local private physicians and public health centers; however, this model proved to have several system failures. Most public health centers are overburdened in many parts of the U.S. (including Philadelphia), leading to significant delays in obtaining an appointment. Without direct oversight from the resettlement agencies, language access and interpretation services, either through a live or telephonic interpreter, were often unreliable (CDC, 2013). Additionally in many states, including Pennsylvania, refugees screened at dedicated PPA sites often needed to transition to a different medical provider for follow-up and ongoing primary care. This disjointed practice may lead to poor continuity of care and preventive care for refugees.

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model can be especially beneficial for refugees because it allows clients to access a screening appointment by the same physician from whom they will continue to receive primary care (Silow-Carroll, Alteras, & Stepnick, 2006; Starfield & Shi, 2004; De Maeseneer, et al, 2003; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Expanding on the PCMH concept, community-centered health homes establish organizational practices, strengthen partnerships, identify community strategies, collect health data, and review health trends (Cantor, et al, 2011).

While the focus of the domestic refugee exam has historically focused more on infectious disease, refugees are also subject to the same health concerns and environmental impact as the broader U.S. population. Refugees should have access to the same primary care, preventative screenings, and immunizations as the rest of the U.S. population. Achieving this objective requires collaboration across professions, institutions, and community organizations. The PRHC is a model of collaboration between resettlement agencies and medical clinics to create an equitable and sustainable system for providing health care and social services to newly arrived refugees.

In 2007, the NSC and the Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) at Thomas Jefferson University piloted a refugee health clinic, creating a symbiotic partnership between a resettlement agency and medical providers. Following initial pilot testing and demonstrable success in terms of performance metrics, refugee community satisfaction, and provider engagement, this partnership model was replicated at numerous medical sites and the other two refugee resettlement agencies serving Philadelphia. Together, this network was formalized through the formation of the PRHC in 2010, which established initial goals of equity in health care access and care quality for all refugees resettled in Philadelphia.

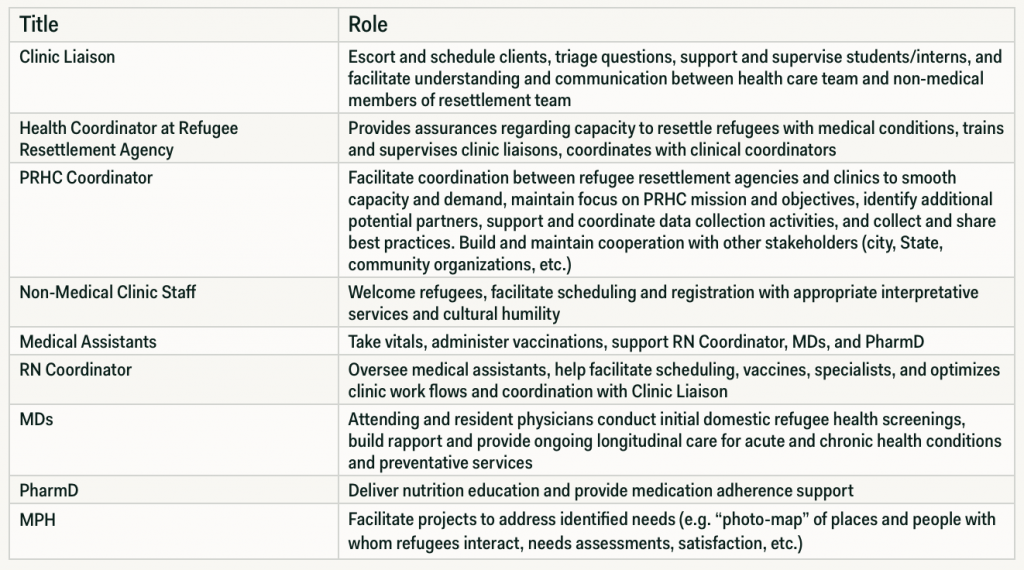

The collaborative has continued to expand and evolve since its inception. Collaborative efforts began with NSC sending an intern to escort patients to DFCM. This escort was critical in (1) ensuring patients navigated from NSC to DFCM, (2) obtaining recommended labs and x-rays, and (3) facilitating follow-up or specialist appointments. All of these efforts were also supported by a registered nurse at DFCM. Now as part of the PRHC model, each clinic is partnered with a resettlement agency staff member (Clinic Liaison) who is the primary point of contact between the clinic and resettlement agency (Table 1). This Clinic Liaison ensures clients receive quality care and communication that meets their needs. Specifically, the clinic liaison escorts clients to the first appointment and provides assistance with registration, filling prescriptions, scheduling testing, and scheduling follow up or specialist appointments. Although not all clinical sites have the capacity to dedicate a nurse to the refugee care effort, all sites offer complete access to all care coordination services (e.g., social work, case management, medical assistants, etc.) available to their non-refugee patients.

Based on provider and client feedback, the specific provider-resettlement agency partnership proved successful in community satisfaction, provider engagement, and decreasing time to initial appointments. However, it was recognized that other refugees continued to be dependent on ad-hoc referrals to community health centers in 2011. Therefore, NSC led efforts to move from a system of individual resettlement agency-affiliated clinic dyads to an open clinic network. By April 2012, all clinics began to accept regular referrals from the three Philadelphia resettlement agencies (Figure 1). Not only did this ensure more equitable access to care, it also improved the capacity of resettlement agencies and medical providers to better match service demand with capacity. What started with one resettlement agency and one clinic has now expanded to all three resettlement agencies and eight clinics. Combined, the existing eight clinics have a capacity to serve all existing refugees as well as approximately 24 new patients each week. As a result, PRHC can offer resettlement to individuals with complex medical conditions and now has capacity to expand medical evaluations to meet the growing demands of the U. S. refugee population.

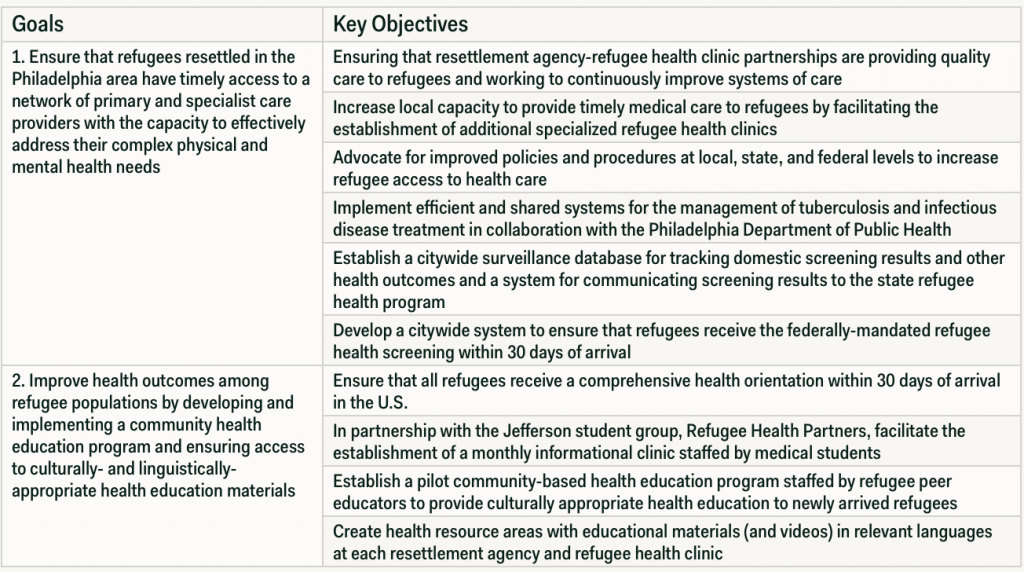

Early PRHC planning and coordination efforts were supported in part by funding from local foundations (the Barra Foundation and the Samuel Fels Foundation; see the Appendix for more comprehensive list). Funds were targeted to support a coordinator to facilitate quarterly meetings with all partners, coordinate refugee health staff at resettlement agencies, and communicate with the city Department of Public Health and the State Refugee Program and State’s Office of Equal Opportunity. In June 2013, with support from the Public Health Management Corporation and the United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey, the PRHC developed a 7 year (2013-2020) strategic plan, which included elements focused on partnership and training, care facilitation, best practice contribution and use, access-focused advocacy, and collective impact measurement (Table 2). Quarterly meetings among the collaborative include discussions on best practices, challenges, future opportunities, and successes. The collaborative does not provide any funding to clinicians. The only funding clinicians receive are Medicaid reimbursement payments for client health services.

With participants from academic medical practices and a federally-qualified health center, PRHC has also enhanced how associated hospital systems address the needs of medico-socially complex populations and individuals with limited English proficiency. PRHC provides opportunities for pediatric and primary care residents, nursing, medical, and occupational therapy students and other allied health professionals to learn and practice global health locally (Weissman, Morris, Ng, Pozzessere, Scott, & Altshuler, 2012). In addition, PRHC continues to form community-centered partnerships with other community organizations that are able to contribute to the needs and successes of refugee clients beyond the initial resettlement period.

In 2007, clinic capacity only allowed 250 new refugee patients per year. By 2012, PRHC coordinated access to primary and specialist health care for over 800 newly arrived refugees in Philadelphia. This more than two-fold increase in capacity now ensures access to care for all refugees resettled in Philadelphia. Having achieved equity of access by allowing all newly arrived refugees to receive quality healthcare, PRHC has been working to ensure consistently high standard of care for all refugees and improve health outcomes.

The PRHC model has also dramatically improved capacity to provide care for refugees with medical complexity (e.g., rheumatic heart disease, cancers, severe trauma, seizures). PRHC has never turned away a patient due to medical complexity, and the local resettlement agencies are recognized by their national affiliates as destinations of choice for refugees with challenging medical conditions (U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, 2015).

In response to stakeholder experiences and recommendations, PRHC has increased coordination with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health to provide health orientation to newly arrived refugees and follow up on infectious disease treatment including monitoring completion of treatment for latent tuberculosis in adults and children. This has allowed better monitoring of public health conditions through improved follow-up and reporting for these conditions. Indeed, one partner clinic has improved latent tuberculosis treatment completion rates to >95%, while others have doubled completion rates (Subedi, et al, 2015).

Implementation of the PRHC model in Philadelphia has improved tracking metrics for all refugees being screened. These metrics will continue to be used to better measure the improvement in health outcomes and overall resettlement success.

Prior to the formation of PRHC, refugees often waited up to 80 to 90 days for an initial screening appointment. Such delays in health care often caused other delays, including delayed entry into school, employment, or social security benefits, and negatively affected overall integration and resettlement success. Currently, newly arrived refugees to Philadelphia are seen on average in 29 days, with the capacity to obtain more urgent appointments (within 1-2 days) when necessary. It is important to note that a critical element of enabling such rapid evaluation has been the development of direct linkages between PRHC and the City benefits office which has led to enrollment in health insurance within 5 days of arrival.

Before PRHC, no specialists or preventative screenings were scheduled except in the case of an extremely serious or life-threatening condition. Now, at a single PRHC provider site, more than 7,980 primary care and 2,790 specialist appointments have been completed. The collaborative model has allowed for expedited preventative screening so that early cases of breast cancer and cervical cancer have been discovered and treated.

Clinics have demonstrated effective management of chronic health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, achieving process metrics and outcomes similar or superior to those demonstrated in their general population (Scott, Tepper, Payton, & Altshuler, 2014; Scott, Altshuler, Kasmari, Payton, & Stache, 2011). Overall, PRHC has improved the collaboration and mutual support between institutions and agencies and ensured that all refugees receive culturally competent medical care by meeting the medical needs of this very diverse population.

The PRHC model relies on clinical and resettlement agency champions, and has recognized the value of common mission, formal and informal communication, and mutual support to achieving shared goals and improved resettlement success. We have learned the importance of combining and sharing resources and training. This has enabled innovative non-competitive relationships with partners. Indeed, PRHC members routinely utilize the participation of other organizations/institutions in the collaborative to negotiate additional support from their own organizations and institutions. The PRHC approach to providing refugees with health care requires a significant investment of time from the refugee resettlement agencies and collaborating clinics. Funding is required for the positions that coordinate this collaborative approach and permit data collection and evaluation, including a coordinator of PRHC as well as support staff at all of the refugee clinic sites and refugee resettlement agencies. Each site needs champions to build the infrastructure needed for collaboration between resettlement agencies and clinical sites including ensuring reliable language access.

In order to meet staffing needs and stay within the budget, the PRHC has partnered with universities and service organizations. Internship and stipend programs are a vital component of this collaborative approach. NSC offers undergraduate and graduate students semester- and year-long internships, during which time the students assist with the health needs of our clients and gain valuable experience in global and public health. NSC also currently has a five-year partnership with AmeriCorps and the Philadelphia Health Corps to provide full-time service members to NSC for 10.5 months at low cost (~$15,000). Interns from the AmeriCorps and the Philadelphia Health Corps fill the Clinical Liaison position. AmeriCorps members have contributed to needs assessments and various other health-related projects to improve the process of refugee health. This has been mutually beneficial for the AmeriCorp members, providing them with unique career experiences.

The PRHC model also provides valuable training opportunities for medical residents. Medical residents at the PRHC receive not only training in primary care, but also exposure to the health needs specific to refugee patients. This exposure prepares them with knowledge and cultural competency related to working with refugees, as well as other individuals with limited English proficiency. Many residents have found this experience to be rewarding because it enables them to work with a global population with unique medical needs and cultural and linguistic differences (Weissman, Morris, Ng, Pozzessere, Scott, & Altshuler, 2012). This experience strengthens the residency program and prepares residents to take their new knowledge and skills to other locations in communities outside of this collaborative. For example, graduates from Thomas Jefferson University’s DFCM residency program have gone on to work in Federally Qualified Health Centers, academic medical centers and engaged in global health overseas. Others have contributed to both the literature on refugee health and the development of other global health and global health at home programs (Pickle, Altshuler & Scott, 2014; Careyva, LaNoue, Bangura, de la Paz, Gee, Patel, & Mills, 2015).

Most importantly, the PRHC has fostered strong relationships with its partners, engaging in research, networking, sharing of best practices between sites, and the development of the strategic plan. Clinics that normally compete with one another are now working together to improve the care of all clients by sharing resources and best practices on a continued basis. This collaboration has led to cross-networking and research collaborations across sites to increase the sample size of studies involving refugees.

The collaborative continues to attract additional partners, building capacity to respond to current and future challenges. Careful expansion has highlighted the strengths of the collaborative model and continued to increase community and organizational capacity. This model has been scaled successfully and may offer opportunities for replication in other communities seeking to improve access and care for local refugee resettlement, especially for those refugees with complex medical conditions.

Although states such as Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota may have similar elements, the PRHC model has not been duplicated or studied in any other areas outside of Philadelphia, and it is still unclear how this will translate in other regions of the country. While PRHC, the Pennsylvania Office of Health Equity, and the Pennsylvania Department of Health Refugee Health Program have worked together to share screening results, there is room to improve this effort. Evaluations of the collaborative and client outcomes are still in progress to better assess the strengths and opportunities for improvement. The results of these evaluations are likely to help further adapt the model to meet the needs of stakeholders. More direct recruitment of community leaders to function as community educators and to provide ongoing refinement of the PRHC model is still in progress.

Through collaborations among resettlement agencies and health clinics, PRHC model provides an effective means to ensure access to timely primary and specialist medical care for newly arrived refugees. The ability to meet the evolving health care needs of refugees with different models of care has the potential to improve health care outcomes for all refugees in the U.S. This collaborative approach is community-focused across agencies and institutions and non-competitive, which has led to faster screening appointments, improved health outcomes, and established medical homes. While there are challenges to overcome, this model has demonstrated success and scalability and offers opportunities for replication in other communities. PRHC members continue to learn and welcome input, recommendations, and contact from any interested parties.

Altshuler MJ, Scott KS, Bishop D, Mills G, Panzer J, & McManus P. (2011). Beyond Vaccines and Infectious Disease: A Comprehensive Approach to Caring for Refugees. The Journal of Family Practice.

Bishop D, Altshuler M, Scott K, Panzer J, Mills G, & McManus P. (2012). The refugee medical exam: What you need to do. The Journal of Family Practice, 61(12): 1-10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). General Refugee Health Guidelines. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/general-guidelines.html. Accessed May 18, 2015.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Refugee Health Guidelines. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/refugee-guidelines.html. Accessed March 1, 2015.

Cantor, J., Cohen, L., Mikkelsen, L., Pañares, R., Srikantharajah, J., & Valdovinos, E. (2011). Community-centered health homes: bridging the gap between health services and community prevention. The Prevention Institute, February.

Careyva B, LaNoue M, Bangura M, de la Paz A, Gee A, Patel N, & Mills G. (2015). The Effect of Living in the United States on Body Mass Index in Refugee Patients. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 26(2), 421-430.

De Maeseneer JM, De Prins L, Gosset C, et al. Provider continuity in family medicine: Does it make a difference for total health care costs? Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:144-8.

Hammoud MM, White CB, Fetters MD. (2005). Opening cultural doors: Providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American and American Muslim patients. Am J Obstetrics and Gynecology. 193: 1307–11.

Office of Refugee Resettlement. About Cash & Medical Assistance. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/programs/cma/about. Accessed May 18, 2015.

Pennsylvania Refugee Resettlement Program. (2015). Retrieved from: http://www.refugeesinpa.org.

Pickle S, Altshuler M, & Scott K. (2014). Cervical cancer screening outcomes in a refugee population. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 12(1): 1-8.

Refugee Act of 1980. Pub. L. 96-212. 94 Stat. 102. 17 March 1980. Print.

Refugee Processing Center, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.wrapsnet.org.

Scott K, Altshuler M, Kasmari A, Payton C, & Stache S. (2011, October). Management of Hypertension in Refugees within a Patient-Centered Medical Home. Poster presented at the AAFP Global Health Conference, San Diego, CA.

Scott K, Tepper J, Payton C, Altshuler M. (2014, Nov.). The Patient-Centered Medical Home as an Effective Framework for Treating Adult Refugee Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Oral presentation at the 2014 North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) Annual Meeting, New York, NY.

Silow-Carroll, S., Alteras, T., & Stepnick, L. (2006). Patient-centered Care for Underserved Populations: Definition and Best Practices (pp. 1-43). Economic and Social Research Institute.

Starfield B, Shi L. The medical home, access to care, and insurance. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 suppl):1493-8.

Subedi PK, Drezner K, Dogbey C, Newbern EC, Yun K, Scott K, Garland J, Altshuler M, & Johnson C. (2015). Evaluation of Latent Tuberculosis Infection and Treatment Completion for Refugees in Philadelphia, PA-2010-12. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 19(5): 565-9.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d.

United Nations General Assembly, Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 14 December 1950, A/RES/428(V), available at: http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c39e1.html[accessed 11 September 2015].

U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (2015). Study of domestic capacity to provide medical care for vulnerable refugees promoting refugee health and well-being. Retrieved from http://www.refugees.org/our-work/refugee-resettlement/reception-and-placement-rp/assets/health-study-full-report.pdf.

Weissman, G, Morris, R, Ng, C, Pozzessere, A, Scott, K, Altshuler, M. (2012). Global Health at Home: A Student-Run Community Health Initiative for Refugees. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23: 942–948.

Brittany DiVito MPH, BSN, RN is a Nurse Practitioner Specialist in Glendale, Arizona.

Colleen Payton MPH is a population health professional committed to examining the social determinants of health and advancing health equity.

Gretchen Shanfeld MPH currently serves as the Senior Director of Program Operations and Strategic Growth at Nationalities Service Center.

Marc Altshuler MD is a Family Medicine Specialist in Philadelphia, PA. He is affiliated with Thomas Jefferson University Hospital.

Kevin Scott MD is a Doctor of Medicine who specializes in Family Medicine at our Cheltenham health center in Philadelphia, PA

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.