Ogunboye I, Zhang Z, Hollins A. The predictive socio-demographic factors for HIV testing among

the adult population in Mississippi. HPHR. 2024;88. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/JJJJ1

The screening of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a critical component of public health efforts to combat the spread of HIV and improve health outcomes for those living with the virus.1,2 In Mississippi, a state with unique socio-economic and healthcare challenges, understanding the factors associated with HIV testing among adults is essential for designing effective interventions and policies. Particularly, Mississippi of all the states in the United States, faces unique challenges related to HIV screening due to its demographic, socio-economic, and healthcare landscape.3

Mississippi is characterized by a population of low socioeconomic status and educational attainment, evidenced by high rates of poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, and uninsured individuals.4,18 In addition, there exist significant disparities in health, income, education, and access to healthcare in the state,16,18 and thereby impacting HIV-care services utilization.17 Furthermore, the predominantly rural population in Mississippi poses additional challenges, including limited access to healthcare services,18 further complicating HIV testing efforts.5,17 Individuals in rural Mississippi have additional barrier to access HIV care due to an inadequate public transportation system4,17 besides the shortage in the health workforce in the rural areas.18 Nonetheless, there have been notable efforts to increase HIV testing rates in the state. Public health campaigns, community outreach programs, and policy initiatives have been implemented to encourage testing and reduce the stigma associated with HIV.4 These efforts are critical in Mississippi where HIV prevalence and incidence rates, HIV-related morbidity, and mortality are relatively high, particularly among certain demographic groups such as African Americans and men who have sex with men (MSM).5

Several factors are believed to be associated with HIV testing among Mississippi adults. Among others are demographic variables such as age, gender, race, locality, education, and socio-economic status, as well as access to healthcare services and awareness of HIV-related information.5,6 These factors play crucial roles in shaping individuals’ likelihood to seek HIV testing. For instance, it is believed that young age, higher levels of education, and better access to healthcare are generally more likely to be associated with HIV testing.7 Conversely, stigma, lack of awareness, and limited healthcare access can significantly impede testing efforts.8

Further, policy interventions and community-based programs play a crucial role in molding HIV testing behaviors. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act, improved funding for HIV prevention and care services, and targeted outreach efforts by the Mississippi State Department of Health (MSDH), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), non-profit organizations, and other partners are capable of influencing HIV testing rates by providing free or subsidized testing services and conducting educational outreach to raise awareness on the importance of early HIV detection.5

The impacts of socio-demographic characteristics on HIV screening have been well documented in many parts of the United States, however, such contextual evidence is scarce for Mississippi. Therefore, this study will focus on examining the relationships between socio-demographic factors and HIV screening to provide valuable insights into the strategic changes needed to more effectively combat the HIV epidemic in Mississippi. We will utilize the most recent BRFSS data to identify the key socio-demographic drivers of HIV testing behaviors among the adult population and highlight areas for improvement. Our goal is to contribute to the ongoing public health efforts to enhance HIV testing rates, reduce new HIV infections, and improve the overall health outcomes for people living with HIV in Mississippi.

Our analysis was based on secondary data, therefore, there was a limited number of socio-demographic variables that could be examined for correlation with HIV testing. Similarly, BRFSS data were collected on the telephone as self-reported, which might potentially introduce some level of respondent bias in the results of this study. Hence, results must be interpreted with caution.

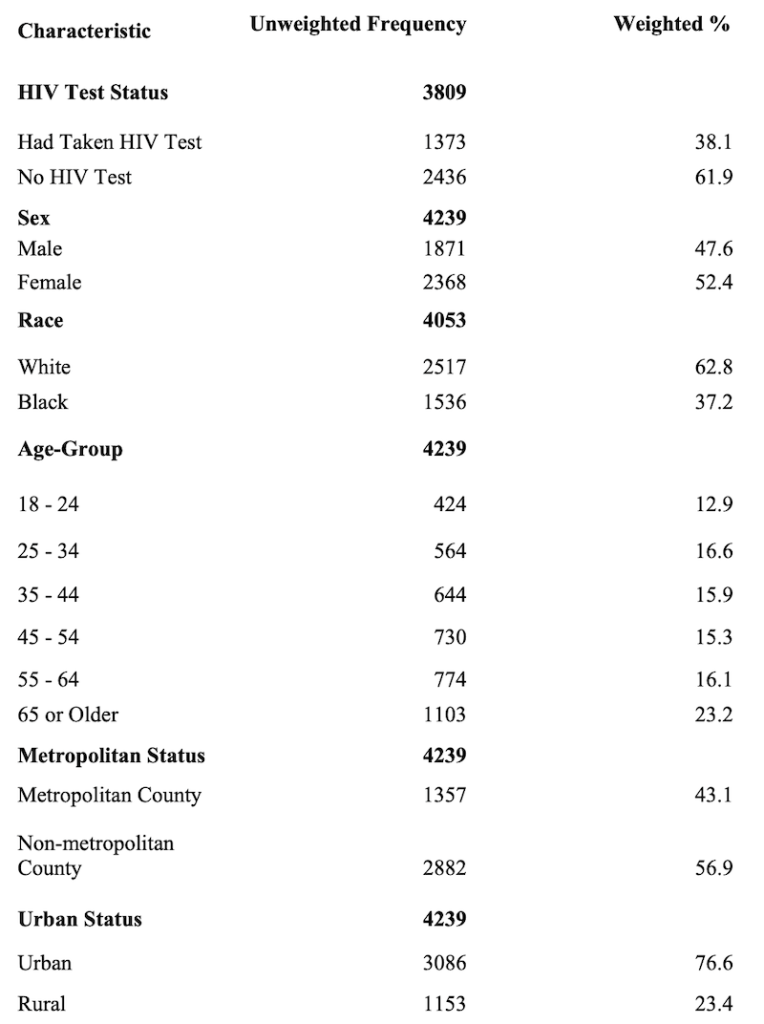

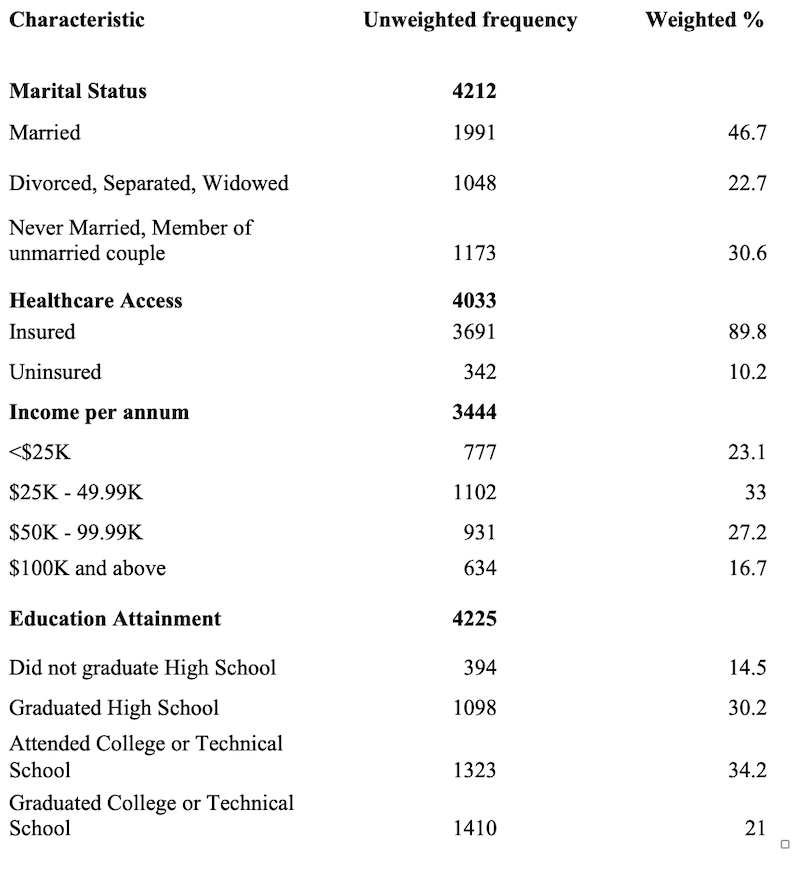

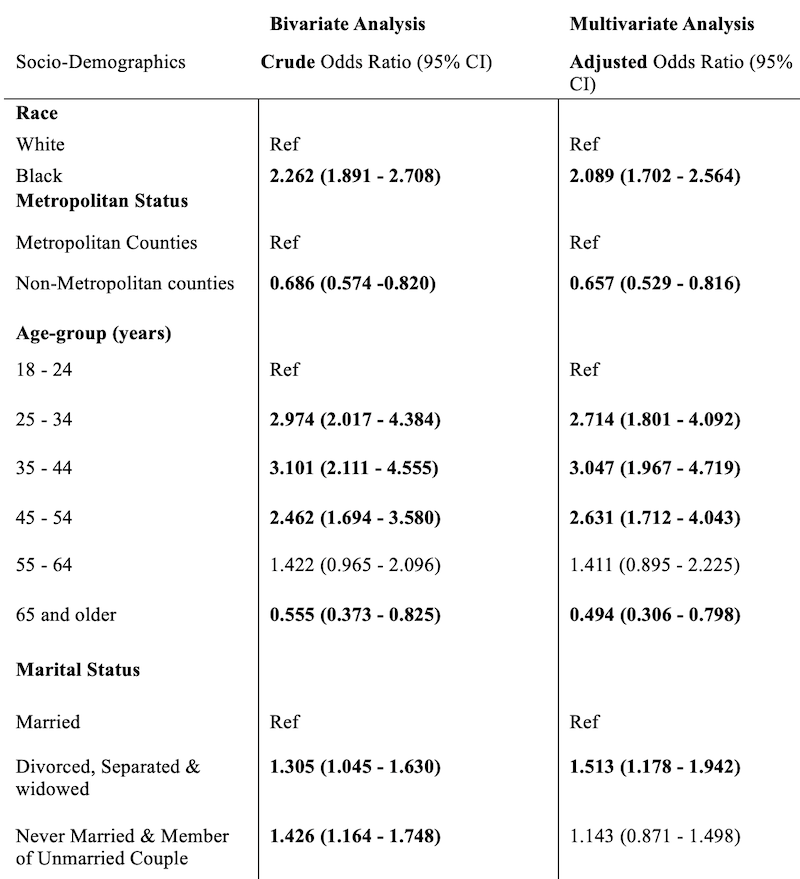

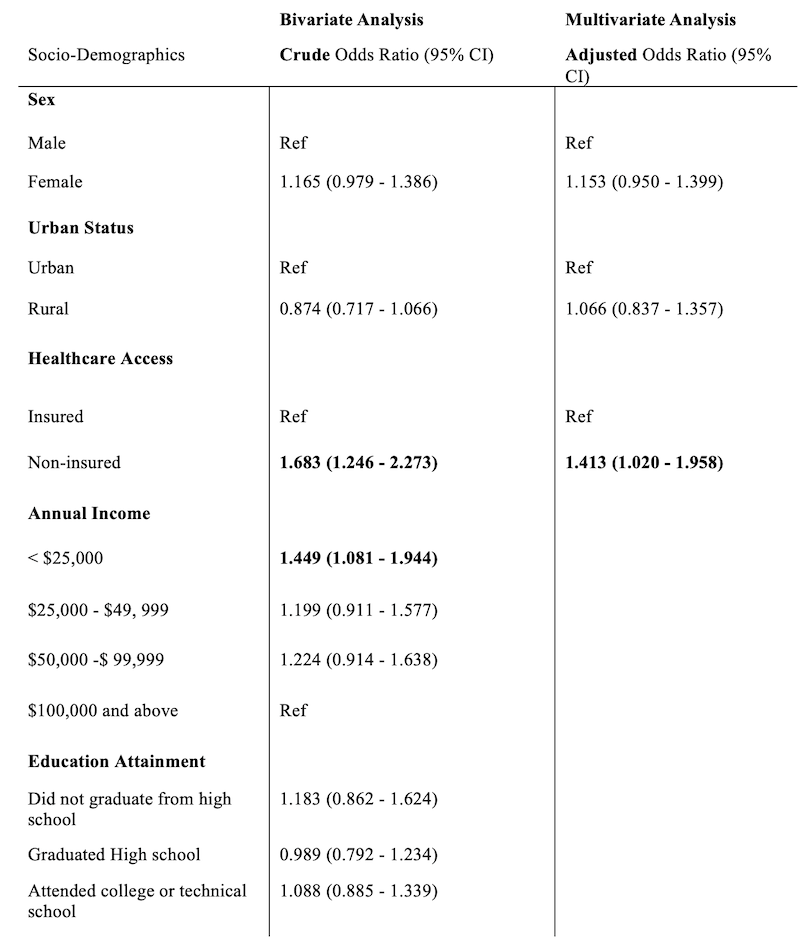

The propensity to have been screened for HIV exhibits a significant positive association with certain demographic factors within the adult population of Mississippi. Notably, these factors are African American race, age within the 25-54 range, metropolitan residency, lack of health insurance, and marital status characterized as divorced, separated, or widowed. These findings emphasize the importance of integrating demographic factors into the design of public health strategies aimed at increasing the uptake of HIV screening services in Mississippi. Tailored interventions are essential, especially in rural areas, to effectively address the lower testing rates among married and unmarried individuals, those with health insurance, the elderly, and the Caucasian demographic. Such targeted approaches are crucial for enhancing HIV prevention and control efforts.

Dr. Igbekele Ogunboye is a graduate student in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Jackson State University. His research areas include epidemiology of chronic diseases, infectious diseases and cost-effectiveness modeling. He received his formal training as medical doctor at University of Benin, Nigeria, and MSc in Health Planning, Policy and Financing at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and London School of Economic and Political Science, UK.

Dr. Zhen Zhang is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Jackson State University. Dr. Zhang’s research interests include applications of machine learning techniques in epidemiological studies; Predictive modeling; Small area estimation methodologies; Complex sampling survey data analysis, etc.

Ms. Ashley Hollins, MS is an esteemed professional currently serving at the Mississippi Department of Health and pursuing a Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) degree with a focus on Epidemiology at Jackson State University. She holds a bachelor’s degree in microbiology from Mississippi State University and a master’s degree in biology, Medical Sciences from Mississippi College. Balancing her work and academic commitments, Ms. Hollins is deeply invested in research, with interests in infectious diseases and the healthcare landscape of Mississippi.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.