Johnson K, Alkhatib S, Kline N, and Griner S. The criminalization of abortion in America: the insidious effect on Black women. HPHR. 2024;82. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/DDDD9

The purpose of this paper is to examine the historical and contemporary impact of abortion laws in the United States, with a focus on the racial disparities affecting Black women. It explores how the criminalization of abortion can perpetuate racial inequities and uphold white supremacy.

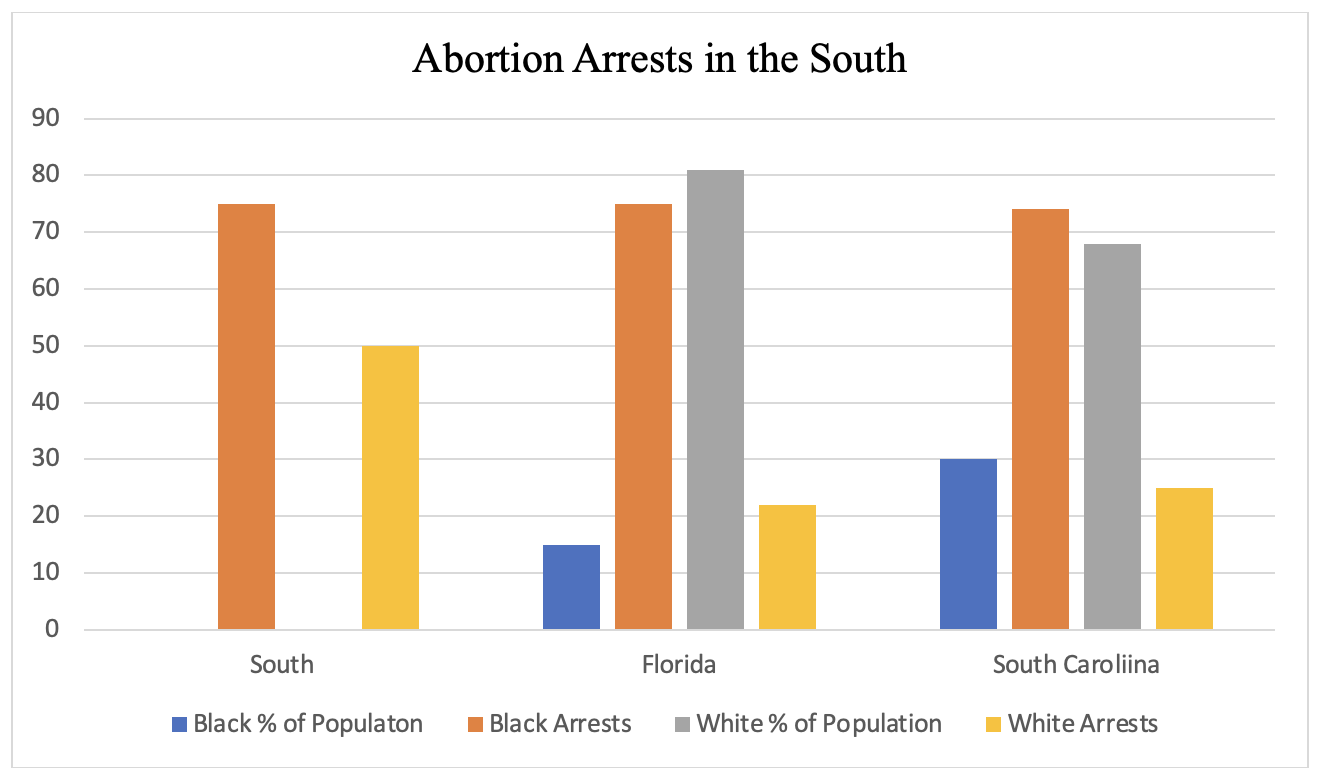

The review highlights that surgical and medication abortions are among the safest medical procedures. However, the criminalization of abortion led to increased maternal deaths and complications. Epidemiological data show that Black women have a higher rate and ratio of abortions compared to white women, and they are disproportionately criminalized for abortion-related offenses. Historical analysis reveals that reproductive control of Black women has roots in slavery and has evolved through various discriminatory practices, including gynecological experimentation and eugenics.

The criminalization of abortion disproportionately affects Black women, perpetuating health disparities and reinforcing systemic racism. The overturning of Roe v. Wade exacerbates these issues, highlighting the need for decriminalization and destigmatization of abortion. Advocacy for reproductive rights, particularly for marginalized groups, is essential.

Abortion in the United States is not a new subject. In the 15th century, abortion was practiced using herbs or medications and was viewed as socially unacceptable but not illegal.10,11 By the mid-1800s, a campaign, spearheaded by the American Medical Association, began to criminalize abortions and was referred to as the “century of criminalization.”10,12 They argued abortion was both immoral and dangerous due to the alleged “incompetence” of physicians that practiced abortions.10,12 Skilled Black midwives practicing obstetrics were viewed as a “threat” to white men entering the field and midwifery was called a “degrading means of obstetrical care” mostly because it was coming from Black women, specifically.10 Not only did it become a battle of abortion’s legality but also between the “elite” physician versus the “irregular” provider and white versus Black.10,13 As the face of obstetrics turned white and male, Black women were denied from being both doctors and patients of renowned hospitals.13 By the 1910s, abortion was illegal in every state; abortion bans had exceptions to save a patient’s life, however, this decision could only be made by physicians, who at the time, were principally men.12

Simultaneously, the U.S. was experiencing an influx of immigrants, which made legislators support abortion bans to force upper-class white women to have children.12 After abortion criminalization, each state passed its own statutes that indicated when a woman could seek an abortion, which created a highly volatile climate that led to more problems due to uncertainty surrounding the legality and availability of abortions depending on their locations and variations in law.10 Because of the uncertainty during this time, many women turned to illegal abortions – thus estimating about 1.2 million illegal abortions occurring in the pre-Roe era.10 Because of the illegality of abortions, they were performed through unsafe practices causing almost 18% of maternal deaths in 1930.12

Throughout the 1950s to 1970s there was national advocacy for abortion law reform, which led to some states repealing their abortion bans or expanding their abortion exceptions.12 In 1970, New York became the first state to legalize abortion and had the first free-standing abortion center.12 At the same time in 1970, Jane Roe filed a lawsuit against Henry Wade who at the time was the District Attorney in Dallas County.14 She challenged the Texas law that made abortion illegal except by doctor’s orders to save the mother’s life. In 1973 the Supreme Court ruled that the state laws were vague and negated her right to privacy protected by the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments.14 The Fourteenth Amendment upholds the individual right to privacy and a woman’s right to choose an abortion is protected under this amendment.14 Under this law the state could not regulate the abortion decision in the first trimester, regulations related to maternal health could be imposed in the second trimester, and in the third trimester once the fetus reaches “viability” a state can regulate or completely prohibit abortion.14

From 1992 to 2020 there were several Supreme Court cases that upheld the precedent of Roe v. Wade. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey upheld the Constitutional right to abortion however it introduced the “undue burden” framework that made it challenging to protest laws that were not an absolute prohibition of abortion.12 The undue burden framework says that challenges must prove that a law would completely hinder someone from receiving an abortion. After Casey, several states implemented medically unnecessary abortion restrictions because they do not contribute to “undue burden”.12 In 2007 the Supreme Court upheld the first federal legislation that criminalized abortion in the cases of Gonzales v. Carhart and Gonzales v. Planned Parenthood Federation of America.12 These cases allowed Congress to ban second-trimester abortion procedures and overruled a key component of Roe in that patient’s health had to be the greatest concern in restrictive abortion laws.12 In Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) and June Medical Services v. Russo (2020) the Supreme Court struck down medically unnecessary abortion restrictions that would cause abortions to be inaccessible in Texas and Louisiana.12

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution does not mention abortion and therefore does not grant abortion as a right.15 This overturned the previous precedent cases of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. By overturning Roe, the Supreme Court removed any federal abortion protections that disallowed states to prohibit abortions before viability.15 Because Roe recognized a fundamental right to privacy, the overturning of Roe also brings up questions of other rights, including the right to decide on partners and contraception, furthering the disparities among Black women by limiting their access to healthcare and autonomy over their sexual and reproductive choices.16,17

The biggest gap in the literature is the near impossibility of finding arrest statistics specifically pertaining to abortion. Criminal databases, such as the Bureau of Justice, include homicide as a category of arrest but do not delineate by type. Most records of abortion arrests are through public attention via media or published court opinions.3 Secondly, most abortion literature focuses on medical methods and the psychological effects of abortion. Little recent literature focuses on the effects of criminalization. There is an overall gap that forgets to address Black Women in the abortion and reproductive rights conversation, specifically in academic literature. Though it is 2024, conversations reminiscent of Sojourner Truth’s Ain’t I A Woman? speech and Kimberlé Crenshaw’s call for intersectionality still must be discussed as Black women’s reproductive rights are often forgotten.

Advocating to politicians to change repeal and asking elected officials and local candidates their standing on abortion rights is an important action in maintaining abortion rights. Voting in midterm elections for local officials that support abortion rights and reproductive choice is essential to keeping protections in place for states that currently have them; lobbying

Abortion and bail bond funds across the country also provide people access to abortions and bail people out of jail who have been arrested for abortions. Supporting these programs and advocating for sustainable funding can increase access to care and improve health equity.

Policymakers can advocate for federal laws that protect the right to abortion and advocate for state-level protections and enact laws that protect healthcare providers who provide abortions to their patients. Researchers should conduct studies on arrests made due to abortions from both the provider and patient sides. They should also study the barriers to receiving abortion since Roe has been overturned and how this affects different populations.

The US has a complex, negative past involving reproductive rights, specifically for Black women. From the rise of gynecology that experimented on Black women’s bodies to the present-day jailing of Black women exercising their reproductive autonomy, Black women have suffered most. Overall, the criminalization of abortion disproportionately affects Black women in the US and perpetuates white supremacy, racial capitalism, and social inequities that have been fought against for centuries. There is evidence that universal access to safe abortion is necessary,28 but many states have laws and statutes on abortions that directly oppose the health and well-being of women. The full decriminalization of abortion and access to affordable abortions would both decrease the number of women arrested for using their reproductive rights but also reduce the preventable deaths of women who are not allowed access to abortions. Currently, reproductive autonomy’s future in the United States looks bleak. However, there are grassroots organizers and community organizations actively fighting against the overturn of Roe v. Wade. The role of public health professionals is to advocate for racial and health equity, which is necessary in addressing the current abortion restrictions and criminalization of abortion for Black women.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

National Abortion Federation. Safety of Abortion. 2006.

Goldberg J. Roe v. Wade – Then and Now 2021 [Available from: https://reproductiverights.org/roe-v-wade-then-and-now/

Paltrow LM, Flavin J. Arrests of and Forced Interventions on Pregnant Women in the United States, 1973–2005: Implications for Women’s Legal Status and Public Health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2013;38(2):299-343.

Riley T, Zia Y, Samari G, Sharif MZ. Abortion Criminalization: A Public Health Crisis Rooted in White Supremacy. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(11):1662-7.

Shah SK, Perez-Cardona L, Helner K, Massey SH, Premkumar A, Edwards R, et al. How penalizing substance use in pregnancy affects treatment and research: a qualitative examination of researchers’ perspectives. J Law Biosci. 2023;10(2):lsad019.

Harp KLH, Bunting AM. The Racialized Nature of Child Welfare Policies and the Social Control of Black Bodies. Soc Polit. 2020;27(2):258-81.

Alang S, Hardeman R, Karbeah J, Akosionu O, McGuire C, Abdi H, et al. White Supremacy and the Core Functions of Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(5):815-9.

Harvey M. The Political Economy of Health: Revisiting Its Marxian Origins to Address 21st-Century Health Inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):293-300.

Melamed J. Racial Capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies. 2015;1(1):76-85.

Joffe C. Portraits of Three” Physicians of Conscience”: Abortion before Legalization in the United States. Journal of the History of Sexuality. 1991;2(1):46-67.

Acevedo Z. Abortion in Early America. Women & Health. 1979;4(2):159-67.

Planned Parenthood. Historical Abortion Law Timeline: 1850 to Today 2022 [Available from: https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/issues/abortion/abortion-central-history-reproductive-health-care-america/historical-abortion-law-timeline-1850-today

Goodwin M. The racist history of abortion and midwifery bans: News & commentary. 2020 [Available from: https://www.aclu.org/news/racial-justice/the-racist-history-of-abortion-and-midwifery-bans

Oyez. Roe v. Wade 1971 [cited 2024. Available from: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1971/70-18.

Harmon S. U.S. Supreme Court takes away the constitutional right to abortion. 2022 [Available from: https://reproductiverights.org/supreme-court-takes-away-right-to-abortion/

Paltrow LM, Harris LH, Marshall MF. Beyond Abortion: The Consequences of Overturning Roe. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2022;22(8):3-15.

Kavanaugh ML, Friedrich-Karnik A. Has the fall of Roe changed contraceptive access and use? New research from four US states offers critical insights. Health Affairs Scholar. 2024;2(2).

Kortsmit K, Mandel MG, J.A. R, Clark E, Pagano HP, Nguyen A, et al. Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2019. 2021.

Huss L, Diaz-Tello F, Samari G. Self-Care, Criminalized: August 2022 Preliminary Findings. 2022.

Thompson P, Turcios Cruz A. How an Oklahoma women’s miscarriage put a spotlight on racial disparities in prosecutions 2021 [Available from: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/woman-prosecuted-miscarriage-highlights-racial-disparity-similar-cases-rcna4583.

Carr Smyth J. A Black woman was criminally charged after a miscarriage. It shows the perils of pregnancy post-Roe 2023 [Available from: https://apnews.com/article/ohio-miscarriage-prosecution-brittany-watts-b8090abfb5994b8a23457b80cf3f27ce.

Klibanoff E. Texas woman charged with murder for self-induced abortion sues Starr County district attorney 2024 [Available from: https://www.texastribune.org/2024/03/30/texas-woman-sues-abotion-arrest-starr-county/#:~:text=When%20a%20Texas%20woman%20was,for%20bringing%20them%20at%20all.

Lenzen C. Facing higher teen pregnancy and maternal mortality rates, Black women will largely bear the brunt of abortion limits 2022 [Available from: https://www.texastribune.org/2022/06/30/texas-abortion-black-women/.

Goodwin M. How the Criminalization of Pregnancy Robs Women of Reproductive Autonomy. Hastings Center Report. 2017;47(S3):S19-S27.

Roberts D. Killing the Black Body1997.

Washington HA. ‘Medical apartheid'(Harriet A. Washington). New York Times Book Review. 2007:6-.

Coen-Sanchez K, Ebenso B, El-Mowafi IM, Berghs M, Idriss-Wheeler D, Yaya S. Repercussions of overturning Roe v. Wade for women across systems and beyond borders. Reproductive Health. 2022;19(1):184.

Berer M. Abortion Law and Policy Around the World: In Search of Decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13-27.

Kaeli C. Johnson, MS is a doctoral student in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. Her research focuses on maternal and child health, reproductive justice, and health equity, particularly among racial and gender minority populations.

Sarah A. Alkhatib, MPH is a doctoral student in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. Her research focuses on the intersection between immigrant health and women’s health and leveraging technological advances to bridge healthcare access and minority populations.

Dr. Nolan Kline is an associate professor in the College of Medicine at the University of Central Florida. His research focuses on social and political determinants of health with particular attention to Latinx im/migrant populations and individuals with intersecting racial and sexual and gender minority identities.

Dr. Stacey Griner is an assistant professor in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. Her research focuses on sexually transmitted infection screening, prevention, and control. She uses implementation science and patient-centered approaches to translate public health research into clinical practice.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.