Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a form of domestic violence that can include “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression by a current or former intimate partner.”1 Experiences of discrimination, homophobia, biphobia, and stigma due to gender stereotypes compound this burden and can specifically impact sexual minority women (SMW)’s decisions or ability to seek help and support for their experiences of IPV.2 Using intersectionality and the minority stress model as frameworks, we researched and summarized these factors, and others, to provide an overview of the current knowledge of IPV in our key population that is available in the literature.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016/2017 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults in the U.S. experience “a disproportionately high burden of violence victimization relative to their heterosexual peers.”3 Specifically, the survey found a higher prevalence of lifetime intimate partner-perpetuated contact sexual violence, physical violence, intimate-partner-perpetuated psychological aggression, and/or stalking among lesbian and bisexual women (in all types of relationships) compared to heterosexual women and men, gay men, and bisexual men.3 Approximately one-half of lesbian and bisexual women reported experiencing negative long-term impacts and trauma of IPV, including PTSD symptoms, feeling fearful or unsafe, and needing medical care.3

Beyond the disproportionate effects of IPV experienced by SMW, the effects of stigma around IPV perpetuated by women against partners who are women also have important implications for public health.2 One study interviewed lesbian and bisexual mothers about their decisions to seek help and support after experiencing IPV.2 They found that some mothers received disparaging remarks from police officers they contacted for help, and others were even threatened with loss of custody of their children, which caused many mothers, especially in the latter case, to avoid contacting law enforcement for help.2 Additionally, some of these mothers felt they needed to be covert when reaching out for help or support due to stigma and discrimination, including one mother who said she felt “embarrassed” at the idea of reporting abuse by a female partner.2 Although there are important health disparities and needs of SMW in the context of IPV, there remains a lack of published literature on this topic. Thus, our study objective was to identify the root causes of IPV among SMW.

We have conducted a non-systematic review of the literature (NSRL) on determinants of IPV among SMW in same-sex relationships. Generally, NSRLs are effective in their ability to illustrate health issues through their informative (yet not all-encompassing) review of the literature. We have chosen this approach due to the flexibility and exploratory nature of NSRLs. Since the topic of IPV among SMW is a diverse and broadly defined topic, an NSRL would allow us to include diverse sources and types of literature that might not fit into a systematic review framework. We have included studies that address the prevalence of IPV within same-sex couples in contrast to opposite-sex couples, and both qualitative and quantitative studies of female same-sex couples. Preliminary research led us to search key terms to identify potential determinants of IPV including but not limited to: substance use, previous experiences of IPV, intergenerational violence, minority stress, psychological abuse, depression, isolation, and internalized homophobia. To include a diverse array of literature, not all of the studies we included were specific to SMW in same-sex relationships; some studies included all lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) people. Our review included academic peer-reviewed articles, grey literature (data published for non-academic purposes), and technical reports. In total, we included 23 articles, which is typically the size of the small NSRL.

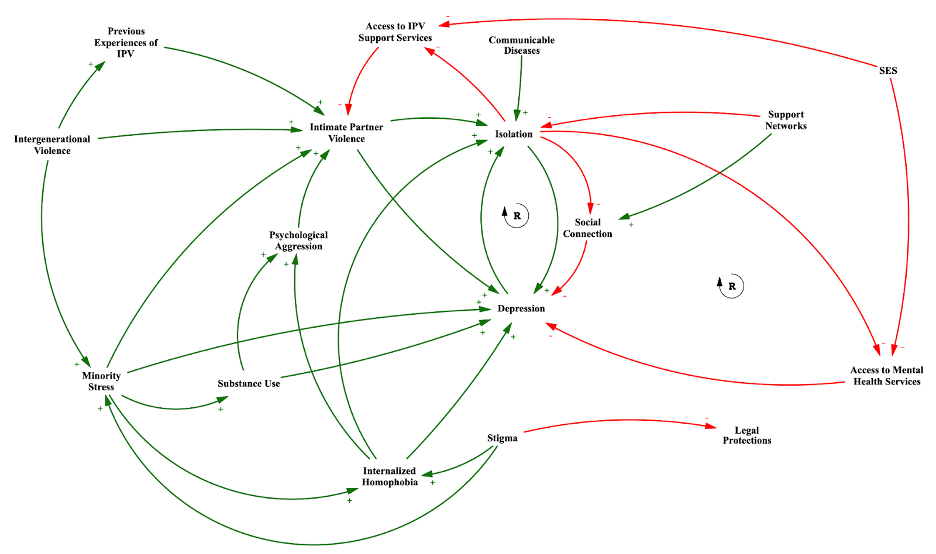

We then developed a causal loop diagram (CLD) to visualize the factors using the Vensim Software.4 CLDs are tools to visualize potential causal relationships between multiple determinants and outcomes.5 These are very beneficial for health systems research and exploring syndemic factors, or the co-occurrence of several health challenges which can exacerbate existing health issues. The development of CLDs does not necessitate a formal systematic review or meta-analysis and often leverages NSRLs or through focus groups.

At the community level, stigma was identified as a determinant of IPV among SMW in same-sex relationships. One study by Wasarhaley et al. found that perceived gender stereotypes of men and women by undergraduate university students affected the way the students viewed cases of IPV with a female perpetrator and female victim; i.e., stereotypes that women are inherently nurturing in relationships and do not pose a physical threat to their partners affected the legal treatment of these cases by the university students.6 Male participants showed more anger towards masculine defendants assaulting feminine victims compared to feminine defendants assaulting feminine victims.6 Likewise, both genders were less likely to mention a defendant’s violent history for guilty verdicts in feminine same-sex couples.6 This research sheds light on how external perceptions and stigma influence IPV among women in same-sex relationships, supporting the inclusion of stigma as a determinant in developing our CLD.

Furthermore, there is existing literature from an intersectional perspective that shows that lesbian and bisexual women have uniquely different IPV experiences due to stigma and stereotypes deriving from monosexism and biphobia. In one study that used vignettes to examine the inner power dynamics of IPV in SMW, monosexism, and bi-negativity were introduced as variables when comparing and contrasting the prevalence of IPV within lesbian and bisexual couples. In particular, findings indicate that bisexual women evaluated vignettes depicting psychological IPV with more negative sentiment than lesbian women.7,8 This corresponds with earlier studies of bisexual victims of IPV, which identified fear of contributing to biphobic societal attitudes if abuse was discussed with peers/social networks.9 As a result, bisexual victims tend to receive less social support and experience poorer mental health compared to their monosexual peers, due to the effects of minority stress.9 Likewise, partner biphobia also contributed to increasing controlling behaviors and violation of sexual boundaries of victims, with perpetrators using biphobic stereotypes, such as non-monogamy, to justify their abuse.9

In SMW, experiencing IPV is associated with adverse mental health outcomes such as depression, and substance use (especially alcohol use) was identified as a determinant of IPV linked to mental health characteristics such as psychological aggression.10,11 Many studies included in this systematic review explore the interplay between alcohol use among lesbian women and their same-sex partners, relationship satisfaction, and instances of psychological and physical aggression.12,13 In particular, Kelley et al. examine the implications of alcohol consumption and poorer relationship adjustment, which is correlated with higher rates of psychological and physical aggression.12 Likewise, the study also notes higher rates of alcohol use, binge drinking, and alcohol dependence for lesbian women in comparison to heterosexual women.7

The specific dynamics of internalized homophobia and its effects on female same-sex relationships have been studied qualitatively.14 Internalized homophobia plays a role in the isolation of victims from support systems, either familial or within the lesbian community.15 A qualitative study that included narratives of IPV victims within lesbian couples found that homophobia contributed to not only the isolation and lack of support for victims but also the denial of IPV prevalence within the lesbian community in general.15 From an intersectional perspective, higher levels of internalized heterosexism (and consequently psychological IPV perpetration) may result from living in a collectivist culture, where the central importance of family helps perpetuate heterosexist ideologies in society.8 Legal and institutional framework also plays a role. For instance, one study found that there is comparatively lower IPV perpetuation in Denmark, which the authors attribute to legal and institutional recognition by the national government, which in turn results in less internalized heterosexism and consequently less IPV perpetration amongst lesbian and bisexual women.8 Since legal recognition leads to improved trust in authorities, this could lower the threshold for reporting IPV to governmental institutions.8

The minority stress model, developed by Ilan Meyer, proposes that individuals identified as part of a stigmatized minority group (such as the LGBTQ+ community) experience unique, ongoing stressors that affect their mental health, including their encounters with discrimination and prejudice, expectations of rejection, concealment of identity, and internalized stigma.9,16 In recent literature, the increased prevalence of IPV within LGBTQ+ individuals has been commonly attributed to this chronic stress factor.9 We aimed to analyze the literature we reviewed through an intersectional lens, considering factors such as socioeconomic status (SES) and race. Seeking mental health or other support services can have a large financial burden on victims of IPV, compounded by lost productivity both in their homes and in their place(s) of work.17 We thus concluded that having a lower SES is negatively correlated with access to IPV support services and mental health services that many victims of IPV are in dire need of. Intersectionally, the highest rates of IPV occur among sexual and gender minorities who are persons of color.8 Additionally, internalized homophobia and biphobia are associated with an increased risk of experiencing IPV in LGBTQ+ individuals.9

We developed a CLD to summarize our NSRL findings on the determinants of IPV in SMW in same-sex relationships (Figure 1). IPV in our key population is directly linked (in positive associations) with both isolation and depression. Isolation was also tied to other factors, including communicable disease (with which it has a positive relationship) and support networks (with which it has a negative relationship). Based on a study that showed that among IPV survivors in their current relationship, nearly one in five experienced an increase in IPV frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the physical confines and mental stressors of living in quarantine, we theorize that communicable disease of any kind that can cause the need to physically self-isolate may compound the feelings of isolation in victims of IPV.10 The desire for support among those experiencing IPV informed our connection between support networks and social connection (with supportive and non-judgmental individuals) as well as between support networks and isolation.2

We identified a reinforcing loop between the variables of isolation, social connection, and depression. We theorized that isolation reduces social connection, and reduced social connection contributes to depression. A larger reinforcing loop is formed when we consider the variable of access to mental health support services; isolation, whether by a partner, the self, or the requirements of a quarantine, was theorized to have a negative relationship with access to IPV support services and access to mental health services. Access to mental health services then in turn is negatively associated with depression, and depression is positively associated with isolation.

Another key variable we included in our CLD was legal protections; Hardesty et al. discussed stigma and homophobia and how some lesbian and bisexual mothers experiencing IPV feared losing custody of their children or not having access to marriage-specific IPV protections due to their lack of marriage rights or unmarried status.2 We theorize that stigma is negatively associated with legal protections for same-sex couples; due to the stigma surrounding LGBTQ+ identities, victims of IPV in female same-sex couples may experience discrimination or disbelief from law enforcement or the judiciary system due to societal attitudes toward their sexual orientation and the dynamics of a female-same-sex relationship.2

Other interlinked factors include substance use, which is linked to increased psychological aggression, as is internalized homophobia (though the latter is not as clear of an association in the literature as of yet).13,14 Internalized homophobia and substance use are also both linked to depression, especially in LGBTQ+ individuals experiencing homophobia and abuse.18 Intergenerational violence and previous experiences of IPV have also been found to be linked to experiencing IPV later in life in our key population.14

We also included minority stress as a variable in our CLD. In SMW, social stigma and discrimination contribute to minority stress, and this then leads to higher levels of internalized homophobia.9,19 Other literature also found that minority stress also contributes to substance use and adverse mental health outcomes such as depressive symptoms in SMW.20,21 We theorize, then, that stigma and intergenerational violence have positive causal links with the minority stress variable, and that minority stress has positive causal links with IPV, substance use, internalized homophobia, and depression.

Although IPV interventions geared at heterosexual couples may be beneficial, the existing literature suggests that the heterosexual model can only be a starting point for treatments and that same-sex couples deserve interventions based on their own particular experiences and needs.22 Likewise, studies have shown that SMW victims of IPV reported heterosexism, discrimination, stigma, ridicule, disbelief, additional abuse, and hostility from IPV services and operators.22

In particular, research conducted surrounding lesbian women highlighted the usage of heterosexist language adopted by legal services and healthcare providers, and that services for LGBTQ+ people were rarely accessible.22 This is also why lesbian and bisexual female victims of IPV minimally use macro-system interventions. Instead, Turell and Herrmann found that victims of IPV wanted peer support within the LGBTQ+ community from fellow queer individuals.23 Likewise, they also understood that not all service providers would be LGBTQ+, but still inclined to LGBTQ+ providers.23 This inclination is due to fear of homophobic reactions “during a time when they did not have the time, energy, or desire to educate a provider about their lesbianism.”23

The creation of new, and care for existing queer third spaces may be key in minimizing the effects of heterosexism. A third space is an accessible social environment outside of one’s home (“the first place”) and workplace (“the second place”) where individuals can meet and connect with others in their community.24 Our CLD stresses the importance of social connection, support, and community because they have been protective of LGBTQ+ people. A well-resourced, queer third space, where sexual minority individuals are open and understood in their identities can serve as a point of intervention for both victims and perpetrators of IPV. Queer third spaces could allow for same-sex IPV intervention to take place in a trusted environment with a community the individual knows and that can provide compassionate care and resources. However, third spaces do not erase the need for larger-level intervention, as they do not completely or legally guarantee the safety of both parties.

Therefore, to implement macro-system changes that orient with the stances of the victims, an important intervention is for legal services, crisis hotlines, healthcare providers, and traditional IPV support services to be well-trained in LGBTQ+ issues that may impact a domestic violence situation. The impacts of communicable diseases and periods of mandated isolation should also be taken into consideration in developing interventions, as the COVID-19 pandemic was a factor that posed a significant burden on LGBTQ+ victims of IPV.10 As we have seen recently with the mpox pandemic, social isolation may continue to pose a significant risk to mental health due to mandatory quarantines for sexual minority individuals.25

This NSRL has limitations that warrant attention. One main limitation is that the studies concerning bisexual IPV victims may include experiences of IPV within relationships with men, which is not the focus of this review. As mentioned before, violence perpetrated by men against women is frequently studied by domestic violence researchers, who often link violent behavior to masculine gender roles and hegemonic masculinity socialization.26 Likewise, masculinity is a common trait in power resources theories that define the power dynamics between partners due to gender, sexual behavior (measured by the sexual and romantic relationships one has with others), and sexual identity.26 For bisexual women, relationship dynamics can change depending on sexual practices.

This indicates that bisexual women experience unique stressors when in relationships with men that are different than the determinants we have identified in our CLD.26 One example is that bisexual women report more pressure to conform to heterosexist ideal beauty norms when in different-sex relationships, which could be a source of psychological abuse.26 Another gap in the literature not included in this NSRL is the consideration of non-binary lesbians, trans femme lesbians, and similar identities. As with the previous discussion on power dynamics, gender identity is a significant determinant that we have not explored in this study due to the scarcity of available literature. Additionally, varying and evolving definitions of the term “sexual minority women” in the literature may have influenced our interpretations.

This review advocates for the need to address IPV within same-sex relationships, particularly among SMW. Throughout this paper, we’ve evaluated previous studies to elucidate the principal determinants contributing to the dynamics of IPV and found that social stigma, depression, substance use, and internalized homophobia are likely factors that contribute to experiences of IPV in SMW.

Our review illuminates possible causal relationships leading to IPV within same-sex relationships. Using a CLD, we offer a visual representation of these complex relationships, emphasizing the necessity to study IPV dynamics within sexual minority populations further. We highlighted obstacles encountered by lesbian and bisexual women in accessing requisite legal protections and support services, often compounded by discrimination and/or systemic barriers. Tailored interventions that are sensitive to the unique needs of SMW are necessary for lesbian and bisexual women in same-sex relationships experiencing IPV.

Looking forward, sustained research, policy, and advocacy initiatives are needed to illuminate and address IPV within same-sex relationships comprehensively. Such initiatives should champion initiatives that address the prevalence of substance use and mental health diagnoses in LGBTQ+ populations. Furthermore, our review points to a need for continued efforts that combat stigma and discrimination within legal institutions, policies, and processes, which would make laws on IPV and domestic violence more inclusive for SMW. Finally, investment in resources and third spaces for sexually minoritized communities should be accessible throughout times of crisis, as it will be crucial in combating the social isolation and the increased IPV that has been associated with a lack of access to community and support networks.

On the whole, this research highlights the needs of sexual minority individuals experiencing IPV among other forms of intersectional stigma and discrimination. We encourage future research to test and validate the relationships hypothesized in this NSLR to better understand the interplay of the factors contributing to IPV in SMW. With more awareness and research into this area, we can better advocate for improved policies and practices for SMW and other marginalized communities to reduce health disparities.

![]()