Farris A, Griner S. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on the life course: a case study using “The Haunting of Hill House” (2018). HPHR. 2024;78. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/ZZZ3

Life course theory posits that early-life experiences that take place during sensitive developmental time periods can influence health behaviors into adulthood. Children who have been exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are often predisposed to many health issues across their lifespan. With the power to impact brain development as well as lifelong health and function, ACEs can fundamentally alter the adults they grow up to be, likely leading them down paths they would not have taken otherwise. Almost 40% of children have experienced at least one ACE, and multiple studies have confirmed the link between ACEs and future chronic health issues, mental health conditions, alcohol and substance use disorders, increased health risk behaviors, and premature death. Using a life course perspective lens, this case study sought to explore the impact of ACEs on the life course by analyzing a popular psychological horror series, The Haunting of Hill House (2018).

Alternating between flashbacks and present-day life, themes and concepts aligned with life course theory are presented throughout the series to further illustrate how early-life traumatic experiences can make children vulnerable to negative health outcomes in the future. This includes examples of life course constructs such as developmental risk and protection, linked lives, trajectories, transitions, and major life events.

This paper uses a case study to apply and provide examples of life course theory concepts, which are often abstract and difficult to understand. Aside from telling a compelling story about the impacts of trauma and grief on health, The Haunting of Hill House (2018) is the epitome of how early-life experiences and presence of a reliable support system can impact one’s path towards adulthood, further reinforcing how necessary it is to protect, nurture, and advocate for children during such sensitive developmental periods in the life course.

To interrupt the cycle of childhood adversity and ensure that all children are positioned to achieve health equity, it is imperative to understand the impact of early adversity across the life course.1 The purpose of this case study is to provide an overview of life course theory and delve deeper into the effects of adverse childhood experiences on adulthood by presenting a case study application of life course theory to a television series, The Haunting of Hill House (2018). Specific examples of concepts, themes, and experiences aligned with life course theory and adverse childhood experiences are highlighted below.

Life events are abrupt changes that significantly impact one’s life course.3 According to the Social Readjustment Rating Scale created by psychiatrists Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe in 1967, the most stressful events in order are the death of a spouse, divorce, marital separation, and death of a close family member,3 all of which the Crain family endured except for divorce. Although Hugh rescues the children during Olivia’s mental health crisis, they ultimately witness him leaving their mother behind, and this strained the once strong relationship he had with his children. Nellie’s husband Arthur unexpectedly died from a brain aneurysm, putting her in a worsening state of emotional distress. Olivia and Nellie both died by suicide at Hill House twenty-six years apart. Steven’s wife Leigh finds out about his secret vasectomy after visiting a fertility clinic together, which later resulted in a marital separation. Theo confessed to collecting her share of the royalties from Steven’s Hill House novel after lying to Shirley about not taking them, and Shirley kicked her out of the guest house she was living in. Of these, the most impactful life event was moving into Hill House to begin with, as this derailed the Crain family’s life course entirely.

As presented here, The Haunting of Hill House (2018) incorporates concepts and themes aligned with life course theory and presents numerous significant ACEs experienced by the children. Aside from their individual and collective anomalous experiences, the children witnessed their mother’s mental health slowly decline; were almost poisoned by their mother during her mental health crisis; watched their father consciously leave their mother behind; endured losing their mother to suicide; and dealt with the eventual estrangement of their father thereafter. These adverse experiences happened early in the children’s life courses, predisposing them to negative health outcomes over time. With little to no support in the aftermath, the lingering grief and trauma that followed took a detrimental toll on the health outcomes of all five children: from harboring years of resentment and anger towards one another, to abusing alcohol and illegal substances to help numb the pain, to suffering from debilitating depression that later resulted in another suicide in the family. These health outcomes exhibited by the Crain children are consistent with previous research directly linking ACEs to negative health outcomes in adulthood.5,10 The strong family unit the Crains displayed before moving into Hill House was shattered within a short time, yet the aftereffects reverberated throughout the rest of their lives.

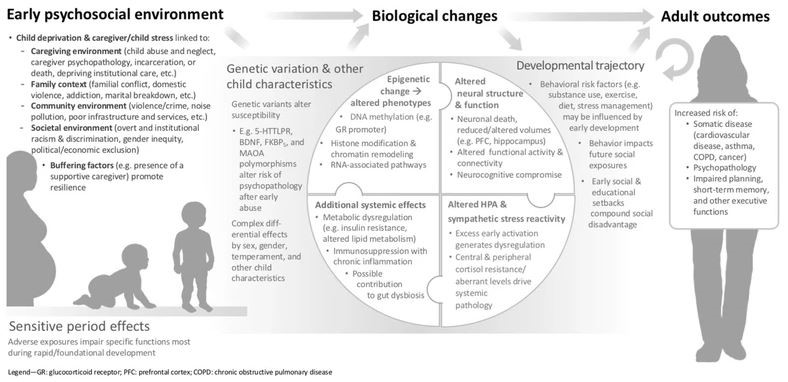

ACEs will continue to threaten health equity without a strategic, coordinated public health approach to address them as early as possible.6 Life course intervention research is an emerging discipline that seeks to improve health trajectories by shifting critical developmental processes to prevent or reduce the impact of adverse outcomes early in life.20 Different from traditional medical interventions, which focus exclusively on disease management, illness prevention, and health promotion, life course interventions focus on health development through acquisition of developmental capabilities that aim to equip children and adolescents with the tools to thrive in adulthood.20 This area of intervention science encourages researchers to consider the biological, psychological, genetic, epigenetic, and environmental processes that occur across the life span to better understand how they influence health development.20 It is crucial that life course interventions are health equity focused and consider the varying circumstances and lived experiences of the populations they aim to serve.15 Very few life course interventions have been implemented, but emerging evidence suggests that life course approaches may be suitable for providing holistic, contextually responsive interventions among young populations.21 The Crain children likely could have benefitted from this type of intervention with a special emphasis on grief processing and trauma recovery.

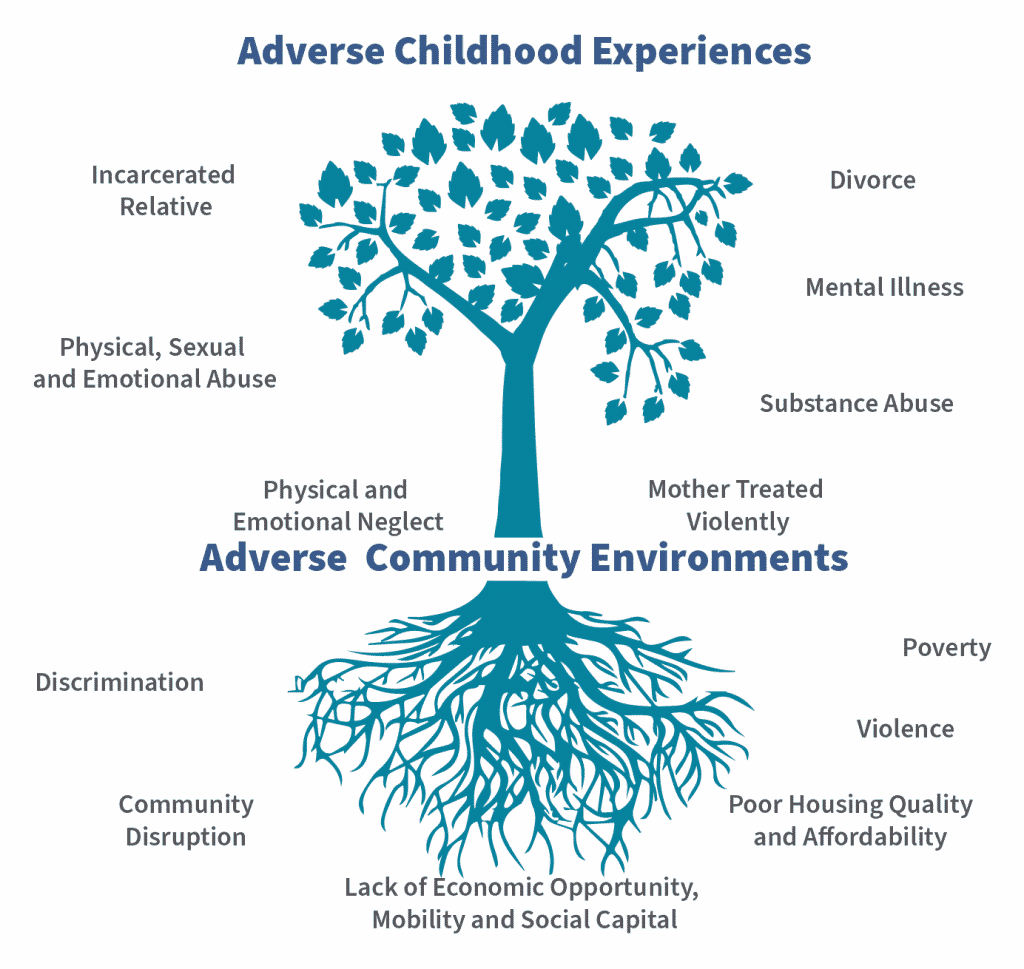

Similarly, the trauma experienced by the Crain children could have been addressed through resiliency practices that instill ways to cope with stress and negativity by fostering healthy coping strategies, confidence, and creation of dependable support systems.22 Successful ACE prevention strategies have resulted in higher academic achievement as well as reductions in depression, suicidal behaviors, incarceration rates, and substance use.23 Examples of evidence-based prevention strategies include early childhood home visitation programs, such as the Nurse Family Partnership program, that is associated with reductions in child abuse and neglect as well as improvements in the parental life course;24,25 after-school programs, such as After School Matters, that has improved graduation rates and decreased the likelihood of drug or gang involvement;24,26and skill-based learning programs, such as Life Skills Training and Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS), that teach youth how to manage stress, resolve conflicts, and manage their emotions and behaviors, further contributing to reductions in depression and anxiety, alcohol and drug use, and suicidal thoughts and attempts.24,27,28 Legislative policies can also aid primary prevention efforts by focusing on reducing ACE risk factors (such as housing insecurity, food insecurity, and domestic violence and neglect) as well as supporting ACE protective factors (such as earned income tax credit, paid family leave, Medicaid expansion, early home visitation programs, and parental education).13,24 Figure 2 highlights how the presence of these risk factors in the community can directly influence ACEs exposure.29 State and territorial health agencies have the power to directly and indirectly shape public health policy, and creating policies based on public health expertise can help to decrease ACEs prevalence within their respective communities.30

Intervention post-exposure to ACEs typically involves victim-centered services and trauma-informed care tailored for children, adolescents, and adults.23 Evidence-based, child-focused treatment approaches include child-parent psychotherapy for young children up to age 6 that have experienced a wide range of trauma; attachment, self-regulation, and competency (ARC) framework for children, adolescents, and young adults up to age 21 who have experienced chronic traumatic stress or ongoing exposure to adverse experiences; and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) for youth up to age 21 who have experienced abuse or trauma.31 The ARC method likely would have been an effective treatment method for the Crain children as research has shown reduction in posttraumatic stress symptoms, improvements in mental health, and increases in adaptive and social skills.31 More recently, preliminary research findings support the application of the ARC method to emerging adults with previous ACEs exposure.32 Sadly, the Crain children mostly suffered in silence as they received little to no emotional support or closure following their mother’s unexpected death and father’s estrangement, resulting in the formation of unhealthy coping strategies and lack of a strong, dependable support system.

Several limitations exist within this case study. Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that the children experienced frequent anomalous events that may or may not represent realistic scenarios; however, this paper ultimately sought to address the long-term impact of those events on their individual life courses, further emphasizing how childhood adversity has the power to fundamentally alter the adults they grow up to be. Secondly, the flashbacks alternated between childhood and adulthood, leaving out a key developmental period within the life course: adolescence. Not only did this make it difficult to understand how the children were raised and cared for by their aunt, but it also made it impossible to pinpoint exactly when the negative health outcomes started manifesting, and whether early intervention could have prevented them from suffering as much as they did in adulthood.

All members of the Crain family suffered through many psychological, stressful, and emotional events that greatly impacted their individual life courses. However, exposure to such experiences made the children especially vulnerable to negative health outcomes that may not have emerged otherwise, with the two youngest suffering the worst health outcomes in adulthood. Unable to fully understand and heal from what happened at Hill House, the Crain children developed unhealthy coping mechanisms in adulthood that included relying on both material and emotional crutches to help counteract the pain. Aside from telling a compelling story about the impacts of trauma and grief on health, The Haunting of Hill House (2018) is the epitome of how early-life experiences and presence of a reliable support system can impact one’s path towards adulthood, further reinforcing how necessary it is to protect, nurture, and advocate for children during such sensitive developmental periods in the life course.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Alexandra Farris is a Project Coordinator in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Dr. Stacey Griner is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Health at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.