Grant C. COVID-19 and malaria vaccine advanced market commitments: opportunities to incentivize investment in Africa’s vaccine manufacturing industry. HPHR. 2023;73. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/UUU1

Using push dynamics to drive the purchase of commodities with forecasted demand, the advanced market commitment (AMC) model has been applied to the development of vaccines catering to low-income countries in Africa and the globe. This model is currently the driving force behind both the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to countries unable to afford open market prices and the roll out of the RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix) malaria vaccine in the WHO Africa region.

This literature review instills a comprehensive understanding of the costs associated with vaccine manufacturing development in the Africa region and draws particular focus to the prices paid by African national governments for the recently rolled out COVID-19 vaccines through the COMAX AMC as well as the estimated costs (based on birth cohort data and DPT vaccination coverage data) of the recently WHO recommended malaria vaccine program.

Ethiopia, a GAVI supported country, is projected to pay between 4.2 and 9.9 million USD annually to vaccinate its target population with RTS,S/AS01b. GAVI ineligible countries such as South Africa and Egypt are projected to spend approximately 15.5 million and 43.3 million USD respectively. Of the GAVI ineligible and self financing countries, those with COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing capacity such as South Africa are able to access vaccine costs at 10 USD/dose compared to the 37 USD/dose spent by the 8 countries without manufacturing capacity.

Investment in existing vaccine manufacturing companies in Eastern and Western Africa has projected growth with CAGR as high as 37% within 10 years. By purchasing and procuring vaccines from local regional manufacturing hubs, a number of donor un-supported self-financing countries in Africa have the potential to save up to 10 USD per vaccine dose.

Globally, 19.5 million children under 1 year of age do not have access to basic vaccines available through country Expanded Immunization Programs (EPI) and are therefore at risk of vaccine preventable diseases.(1) Historically, vaccines developed for high income markets have been introduced in developing countries after a delay of 10-15 years.(2) In the current model of vaccine development, the governments of affluent nations primarily invest in vaccine basic science research and development (R&D) while commercial Pharma funds both the clinical trials and the scale up manufacturing of these vaccines. The scale up funded by Pharma is approximately 2/3 of the total cost of vaccine production.(3) GAVI, the Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunization, was launched in 1999 as a daughter to the Children’s Vaccine Initiative with the primary goal of developing and procuring vaccines addressing AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, the big 3 diseases responsible for a large proportion of global mortality. A partnership between the WHO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and Bill and Melinda Gates, GAVI purchases vaccines procured by UNICEF at the lowest manufacturing costs on behalf of developing country governments and is currently supporting the EPIs of 39 countries in the Africa Region.(4)

Drawing from previous models used to expedite the development of the meningococcal C vaccine in Europe in 1996 and the ideology behind CDC’s Vaccines for Children Program, economist Michael Kremer employed push marketing strategies to construct the advanced market commitment (AMC) costing model to incentivize current innovation in the field of vaccine development.(2) With the AMC model, major pharmaceutical companies as well as government research agencies are incentivized to pursue the R&D of vaccines benefiting low income countries by the contracted promise that the governments of these countries as well as philanthropic sponsors will purchase them once produced. Following the global attribution in 2004 of 1 in 10 deaths in children under age 5 to a then vaccine preventable disease, the AMC model was used to roll out the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) to 73 GAVI eligible countries between 2009-2019.(5) In this proof of concept study, four companies including GSK, Pfizer, Serum Institute of India, and Panacea Biotech were contracted 1.5 billion USD to supply 200 million annual doses of PCV priced at 3.50 USD per dose to Kenya, Sierra Leone, Gambia, Mali, Cameroon, and other GAVI supported countries.(6) Although this 10 year AMC contract managed to narrow the gap between PCV vaccine development and immunization introduction in the serviced countries with 56 of the 73 GAVI eligible countries introducing the vaccine by 2016, it did not encourage innovation or increased manufacturing capacity in these low income countries.(7)

Launched in 2001, the Meningitis Vaccine Project (MVP) not only introduced the Neisseria Serogroup A targeting MenAfriVac to Africa’s meningitis belt, but it also improved the manufacturing capacity of the then emerging vaccine producer Serum Institute of India.(8) Following an epidemic extending from Senegal to Ethiopia that claimed 25,000 lives between 1996-1997, the MVP was implemented by the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH) and the WHO to develop a conjugate vaccine at the low price of 0.40 USD per dose. Given that this low price offered very little incentive to manufacturers in industrialized developed nations, funds donated by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation set the grounding for an AMC contract that guaranteed the Serum Institute of India 0.50 USD per dose in exchange for capital investment in its own production capacity.(9) Investment of 17 million USD in its production facility coupled with a transfer of conjugation technical support from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allowed the Serum Institute to manufacture the meningococcal vaccine that was eventually introduced to Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger in 2008 and to Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon in 2011.

According to the most recent World Malaria Report 2021, the WHO Africa region continues to carry a high proportion of the global malaria burden, with the region bearing 95% of all malaria cases worldwide and 96% of case mortality.(10) More than half of the global malaria mortality is attributed to children under 5 years of age born to four countries in this region: Nigeria (31.9%), the Democratic Republic of Congo (13.2%), United Republic of Tanzania (4.1%), and Mozambique (3.8%). 2/3 of the malaria deaths reported in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2020 have furthermore been associated with healthcare disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. 172,465 lives to date have been claimed by COVID-19 in the Africa region, accounting for 2.8% of COVID-19 global mortality.(11) To support access to COVID-19 vaccines in low and middle income economies in Africa and across the globe, GAVI launched the COVID-19 Vaccination AMC (COVAX AMC) in June 2021 with 2 billion USD donated through philanthropy and the private sector.(12) Following the success of the Malaria Vaccine Implementation Project in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi, the WHO recommended the use of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in all of Sub-Saharan Africa.(13) Although these two AMC opportunities are both serving developing countries in the Africa region, they contract multinational vaccine manufacturers and pharmaceutical giants such as GSK and Pfizer and leave little room for capacity building of Africa’s vaccine manufacturing industry.

This literature review consolidates information from disparate sources to instill a comprehensive understanding of the costs associated with vaccine manufacturing development in the Africa region. This review draws particular focus to the prices paid by African national governments for the recently rolled out COVID-19 vaccines through the COMAX AMC as well as the estimated costs of the recently WHO recommended malaria vaccine program.

A Boolean search with combinations of keywords ‘advance market commit*’, ‘good manufacturing practice’, ‘drug industry’ or ‘pharma’, and ‘Africa’ was conducted using Ovid Medline, Embase, and Web of Science databases. Grey literature covering the vaccine manufacturing industry in Sub-Saharan Africa was collected from WHO, UNIDO, GAVI, and the Center for Global Development online platforms. References unrelated to vaccine funding and the region of focus were excluded.

COVID-19 vaccine price data was acquired from the COVID-19 Vaccine Market Dashboard, a resource made public by the Unicef supply division: https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard.(14)

Estimates of national expenses for the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine were based on birth cohort data and DPT vaccination coverage data supplied by the UN Population Division (https://population.un.org/wpp/) and the SDG data portal (https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/dataportal). (15,16)

SAS 9.4 Software was used to perform descriptive statistical analysis of COVID-19 vaccine price data. Minimum and maximum national expenses for future malaria vaccine programming were calculated with the following formulas:

Cmin= (2020 Country Population Age 0) * (DPT Vax Coverage %, Min Coverage 2000-2020) * (GAVI Co-financing Index) * (4 doses in vaccine regimen)

Cmax= (2020 Country Population Age 0) * (DPT Vax Coverage %, Max Coverage 2000-2020) * (GAVI Co-financing Index) * (4 doses in vaccine regimen),

Where Cmin is the minimum cost of malaria vaccine distribution, DPT Vax Coverage % is the annual percentage of each country’s target population reached by diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus vaccine programs, and GAVI Co-financing Index is the price to be paid by national governments based on their GAVI status.

Launching commercial vaccine production facilities requires significant capital investment on the order of tens to hundreds of millions of dollars.(17) Such large investments are needed to cover the operating costs of acquiring raw materials, skilled personnel, and facility equipment. Along with this monetary investment comes the extensive timeline needed to establish a fully integrated vaccine production facility, a timeline during which there is usually no income generated by the production plant. In order to enter the world market, vaccine manufacturing facilities also must comply with cGMP (current good manufacturing practices) as determined by the WHO. Acquiring approval for global market entry requires that each vaccine product be pre-qualified by the WHO and that the vaccine’s country of manufacture has a functional national regulatory authority (NRA).(18) Currently, only 30% of NRAs among WHO member states have the authority to effectively regulate medical products in their countries and the process of establishing the minimum maturity level 3 status needed to operate as a functional body necessitates marketing authorization and licensing, pharmacovigilance monitoring, setting up a national control laboratory, and evaluating the clinical performance of manufactured vaccines. Although transfers of technology can reduce the time duration needed to establish fully integrated vaccine production facilities in developing countries, developing countries often lack the R&D capacity to support these transfers. On the whole, there is a lack of experienced, skilled, and trained people in vaccine production in resource limited countries, beckoning the need for work force capacity building and political support to promote vaccine manufacturing.(17) Governments of developing nations have the onus of enabling local vaccine manufacturing through NRA strengthening and facility capital investment.

In the face of the African Vaccine Manufacturing Initiative launch in 2010, less than 1% of Africa’s routine vaccines are currently locally manufactured.(19) There are 10 established vaccine manufacturing plants in the region with varying levels of capacity: 4 in Northern Africa, 1 in Senegal, 2 in Nigeria, 1 in Ethiopia, and 2 in South Africa (Table 1). These companies are primarily distributed amongst 5 regional trade agreement blocks, with room for production establishment in the CEMAC conglomerate. The majority of these vaccine plants rely on public funding from both government budgets and overseas donor development banks, while Biovac is the only Public Private Partnership 47.5% owned by the South African government. Within the 3 regional vaccine markets in GAVI transitioning countries Nigeria, Kenya, and Sudan, investment opportunities in Africa’s vaccine manufacturing market demonstrates potential growth with CAGR as high as 37.4% over a 10 year period.

In 2019, multinational manufacturing companies such as Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, and GSK reaped over 60% of Africa’s vaccine market value supplying 23% of the total doses to the region with pneumococcal, rotavirus, HPV, and polio products.(23) With pressure to sell at low prices, India’s vaccine manufacturing companies including Serum Institute supplied approximately 68% of the doses delivered to GAVI supported countries in Africa (726 million doses) and recouped 28% of the market value (241 million USD) in 2019. In self-financing African countries, multinational manufacturing had an even larger share of the market value at 77% and 319 million USD. With Nigeria and Sao Tome in phase 2 accelerated transition out of GAVI as of 2017 and 9 countries including Cameroon, Congo, the Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritania, Sudan, and Zambia in phase 1 preparatory transition as of 2019, Africa’s vaccine market is projected to increase in value as these countries will have to procure vaccines through channels other than GAVI. In addition, introduction of Mosquirix into national immunization programs is projected to contribute 0.1-1.2 billion USD to the regional market by the year 2030 while COVID-19 specific vaccines are estimated to compose up to 0.6 billion USD.

In December 2021, GAVI approved a 155.7 million USD investment for the delivery of the RTS,S/AS01b malaria vaccine to interested GAVI supported countries.(24) Developed by GSK, Mosquirix is a 4 dose regimen composed of a recombinant sporozoite antigen to be taken monthly at age 5 months with the last dose scheduled between 15-24 months of age. In alignment with the AMC blueprint, GSK has committed to supplying the first 15 million doses of Mosquirix at 5 USD per dose until the year 2028.(25, 26) Following a technology and patent transfer from GSK, India’s Bharat Biotech is in line to be the sole supplier of Mosquirix starting in 2029. During the first 8 years of rollout, GAVI supported countries such as Mozambique, Uganda, Senegal, and Zambia can expect the Vaccine Alliance to cover 80% of malaria vaccination costs while national governments are expected to pay the remaining 20%. Following this assumption, Ethiopia, a GAVI supported country with a birth cohort size as high as 3.5 million, is projected to pay between 4.2 and 9.9 million USD annually to vaccinate its target population with RTS,S/AS01b. Senegal’s national government is projected to pay between 1.1 and 2 million USD annually to

cover its estimated birth cohort of 530,000. Responsible for the full cost of Mosquirix at 5 USD per dose, GAVI ineligible countries such as South Africa and Egypt are projected to spend approximately 15.5 million and 43.3 million USD for their malaria immunization programs respectively. Addition of the novel malaria vaccine to the EPIs of the WHO Africa region has the potential to increase Africa’s vaccine market value by up to 1.2 billion USD by the year 2030.(23)

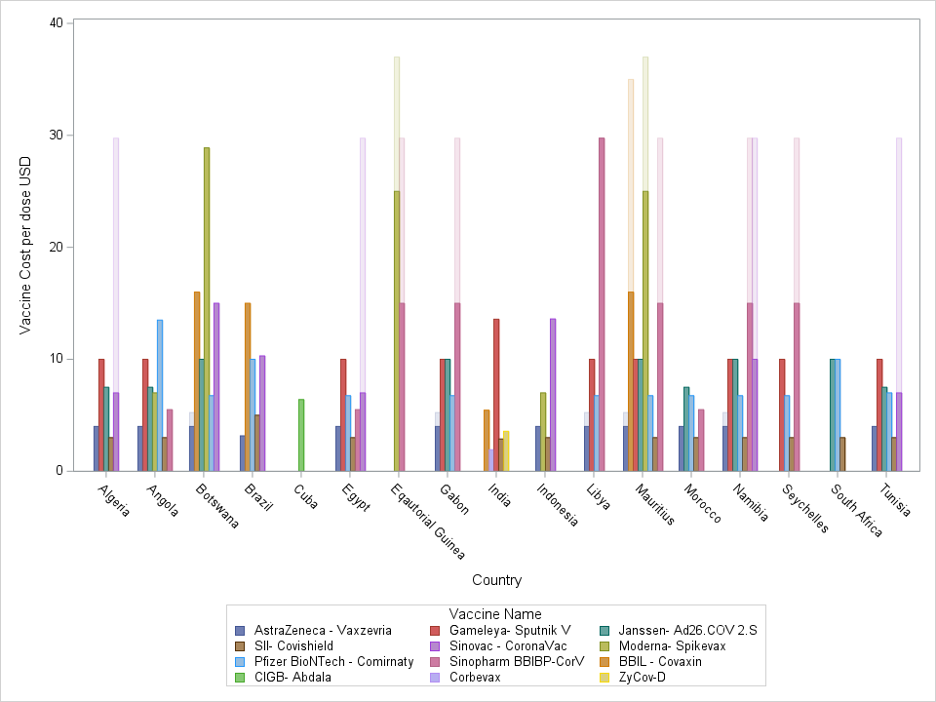

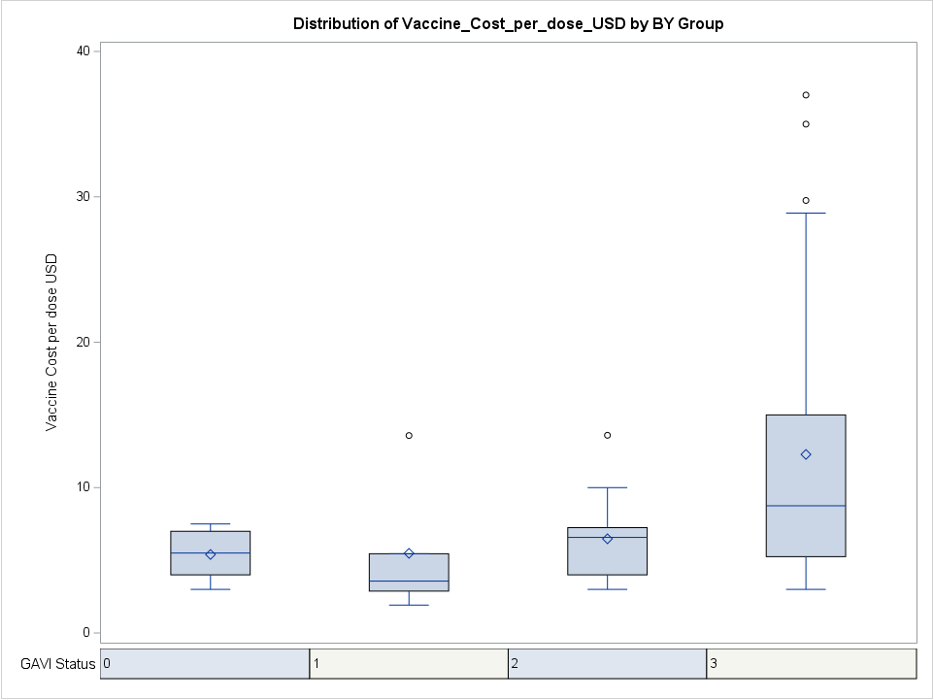

Through the COVAX initiative, the WHO set out to vaccinate 40% of every country’s population by the end of 2021 and up to 70% by mid 2022.(27) In addition to providing the capital to the Serum Institute of India to manufacture 200 million doses of Covishield COVID-19 vaccine at $3.00 per dose for 92 low and middle income countries (LMIC), the COVAX AMC procured, allocated, and facilitated the delivery of other globally manufactured COVID-19 vaccines at the lowest market prices (Figure 1). Four countries (Morocco, Algeria, Arab Republic of Egypt, and Tunisia) that do not qualify for general GAVI support because of their above threshold per capita gross national income (GNI) have benefitted from the lower prices guaranteed by the COVAX AMC initiative while manufacturing at their local facilities.(28) The other 8 countries in Africa that are ineligible for GAVI support and that are not participants in the COVAX AMC (Botswana, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, Mauritius, Namibia, Seychelles, and South Africa) pay the highest market prices up to $37 per Moderna- Spikevax dose (Figure 2). Of the GAVI ineligible and self financing countries, those with COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing capacity such as Brazil (manufacture AstraZeneca – Vaxzevria in Fiocruz vaccine center), Cuba (manufacture Abdala in Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology vaccine institute), and South Africa (manufacture Janssen- Ad26.COV 2.S in Aspen Pharmacare vaccine facility) are able to access vaccines at lower costs per dose. Of the accelerated transition countries, India is able to purchase COVID-19 vaccines at prices lower than those negotiated by COVAX AMC through to its expansive local manufacturing landscape consisting of 21 public and private companies.(29) Once nations graduate out of GAVI support and eligibility, they have the option of procuring vaccines at similarly low market prices directly through UNICEF Supply Division, through direct bilateral agreements with vaccine manufacturers, or through self manufacture. The 11 countries in Africa currently in phases 1 and 2 of GAVI transition as well as the 8 countries ineligible for GAVI support have the potential to decrease their total vaccine expenditure by up to 10 USD per dose by entering the local manufacturing field.

Countries in the WHO Africa region in need of vaccine manufacturing capacity building should have appropriate technical skills, market, and political commitment.(30) Collaboration with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) has allowed India, Brazil, and Morocco to reinforce existing infrastructure for entry into the global vaccine market. Political commitment in the form of export incentives and favorable tariffs for receiving countries benefited India vaccine manufacturing companies during their development and scale up and can be used as tools by Africa’s nationals.(31)The African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization Initiative currently includes the ECOWAS regional pharmaceutical plan, the Zazibona process in Southern Africa, and the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum (AVAREF).(32) Collaboration across these bodies and establishment of regional manufacturing hubs designed to service participating local countries has the potential to make investment in Africa’s local manufacturing economically feasible. Such regional collaboration would not only ensure demand certainty for locally manufactured products but would reduce prices paid by national governments through pooled procurement. Engaging in existing programs that provide vaccine specific training, tapping into the concept of public private partnerships like South Africa’s Biovac, and dedicating adequate resources to vaccine R&D would contribute towards long term sustainability of the vaccine industry in the region. Despite the perceptions of high risk associated with financing vaccine manufacturing projects in Africa, investment in this industry has promising capital gains with CAGR ranging from 11.1-37.4% over a 10 year period.

The WHO recommended addition of Mosquirix to the EPIs of Sub-saharan Africa represents an opportunity for local vaccine manufacturing to enter the market. Although the AMC model guiding the introduction of this novel routine vaccine has contracted a manufacturing industry in India, this advanced commitment can be repurposed to spur the development of Africa’s vaccine manufacturing landscape, by guaranteeing the region a proportion of the market once pre-qualified production is demonstrated. The COVAX AMC currently allows GAVI supported LMICs and countries with vaccine production capacity in North Africa access to low priced COVID-19 vaccines. Involving those African nations ineligible for GAVI support as well as those countries expecting to transition out of GAVI support in advanced purchase commitments for COVID-19 vaccines can not only encourage development of local vaccine manufacturing capacity but also allow these nations access to lower priced vaccines. Since graduating out of GAVI support in 2017 and 2018, Indonesia and Cuba have been able to secure low price deals on routine vaccinations through local production and self-procurement agreements with Indian vaccine manufacturers.(23) India has established its foothold in vaccine AMCs by agreeing to sell their products at the lowest prices in the global market. There is room for local vaccine manufacturing industries in Africa to follow suit and to sell at prices set between the open market and UNICEF to recover appreciable profits.(31)

Table 1: African Vaccine Manufacturing Plants- Investment Opportunities | ||||||||||

Regional Blocks | No. Member States | Vaccine Manufacturers in Region | NRA Capacity (20) | Current Manufacturing Capacity | Investment Opportunity | Invest-ment Size (per facility), $ mn | NPV, 10 years, $mn | Investment Risk Level | Time Frame for Setting Up | CAGR |

EAC: Burundi Kenya Rwanda S. Sudan Tanzania Uganda |

6 | N/A | NRA working towards ML3 | Kenya has 5 companies with sterile filling capabilities and MNCs expressing interest in investment in Vx manufacturing | Brownfield to Downstream Model: Support production of adjacent products | 14 | 40-50 | 50% High Risk | 4-6 Yrs | 11.1-13.6% |

COMESA: Burundi Comoros Dem Congo Djibouti Egypt Eritrea Eswatini Ethiopia Kenya Libya Madagascar Malawi Mauritius Rwanda Seychelles Somalia Sudan Tunisia Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe |

21 | Egy Vac (Vacsera) | NRA achieved ML3 in 2022. | -Drug substance manufacturing -Fill and Finish -Pack and Label -Import for distribution

| Brownfield to Expanding Routine Model: Expand to include HPV, Rota, and novel routine (Malaria) Manufacturing | 5 | 90-120 | 75% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | 33.5-37.4% |

EPHI: Ethiopia Public Health Institute | Initial Work to obtain ML3 | -Pack and Label -Import for Distribution | Brownfield to Downstream Model: Expand Fill and Finish Capacity | 14 | 40-50 | 50% High Risk | 4-6 Yrs | 11.1-13.6% | ||

Institut Pasteur Tunis | NRA working towards ML3 | -Drug Substance Manufacturing -Fill and Finish -Pack and Label | Brownfield to Expanding Routine Model: Expand to include HPV, Rota, and novel routine (Malaria) Manufacturing | 5 | 70-90

| 75% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | 30.2-33.5% | ||

CEMAC: Cameroon CAR Chad Congo Eq. Guinea Gabon Sao Tome |

6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Greenfield to Platform Leapfrog Model: Establish new site producing full products using novel platforms (mRNA) | 190 | 170-210 | 100% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | -1.1- 1.0% |

ECOWAS: Benin Burkina Cape Verde Gambia Ghana Guinea G. Bissau Ivory Coast Liberia Mali Niger Nigeria Senegal S. Leone Togo |

15 | Institut Pasteur Dakar | WHO Pre-qualified | -Drug Substance Manufacturing -Fill and Finish -Pack and Label | Brownfield to Expanding Routine Model: Expand to include HPV, Rota, and novel routine (Malaria) Manufacturing | 5 | 90-120

| 75% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | 33.5-37.4% |

Biovaccines | ML3 Certified in 2022 | -Pack and Label | Brownfield to Downstream Model: Expand Fill and Finish Capacity | 30 | 40-50 | 50% High Risk | 4-6 Yrs | 2.9-5.2% | ||

Innovative Biotech | ML3 Certified in 2022 | -R&D | Brownfield to Platform Leapfrog Model: Establish new site producing full products using novel platforms (mRNA) | 190 | 170-210 | 100% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | -1.1- 1.0% | ||

N/A | ML3 Certified in 2020 | In 2018, Merck announced plans to set up a Vx plant in Accra, Ghana. | Greenfield to Expanding Routine Model: Expand to full value chain (drug substance) production | 190 | 90-120 | 75% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs

| -7.2- -4.5% | ||

SADC: Angola Botswana Dem Congo Eswatini Lesotho Madagascar Malawi Mauritius Mozambique Namibia Seychelles South Africa Tanzania Zambia Zimbabwe |

15 | Biovac | NRA working towards ML3 | -R&D -Drug Substance Manufacturing -Fill and Finish -Pack and Label -Import for Distribution | Brownfield to Expanding Routine Model: Expand to include HPV, Rota, and novel routine (Malaria) Manufacturing | 5 | 90-120

| 75% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | 33.5-37.4% |

Aspen Pharmacare | NRA working towards ML3 | In Nov 2020, Aspen signed prelim agreement with J&J for tech transfer and commercial manufacture of COVID-19 vaccine. | Greenfield to Downstream Model: Expand Fill and Finish Capacity | 14 | 40-50 | 50% High Risk | 4-6 Yrs | 11.1-13.6% | ||

NatPharm | NRA working towards ML3 | In May 2022, Bio Farma expressed interest in transferring of technology to Zimbabwe’s government owned NatPharma.(21) | Greenfield to Platform Leapfrog Model: Establish new site producing full products using novel platforms (mRNA) | 190 | 170-210 | 100% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | -1.1- 1.0% | ||

AMU: Algeria Libya Mauritania Morocco Tunisia |

5 | Institut Pasteur Morocco | NRA working towards ML3 | -Import for Distribution | Brownfield to Expanding Routine Model: In partnership with Recipharm, a plant is to be erected in Casablanca with capacity to produce 20 vaccines including Sinopharm COVID-19.(22) | 500 | 170-210 | 100% High Risk | 5-10 Yrs | -10.3- -8.3% |

Institut Pasteur Algeria | NRA working towards ML3 | -Import for Distribution | Brownfield to Downstream Model: Expand Fill and Finish Capacity | 14 | 40-50 | 50% High Risk | 4-6 Yrs | 11.1-13.6% | ||

Table 1: List of regional trade blocks in WHO Africa region with associated vaccine manufacturing companies and investment opportunities. CAGR= Compound Annual Growth Rate. | ||||||||||

The author declares no relevant personal, commercial, academic, or financial conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this article.

Dr. Chelsea Grant is a recent graduate of Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. She completed her Bachelor of Arts in Neurobiology at Harvard University.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.