Matthews N, Carpenter C. How a historical practice continues to effect our everyday lives. HPHR. 2022;68.

The Global Health Debates is a video series aimed to democratise knowledge of complex global and public health topics into accessible summaries for a diverse audience. We believe that the world’s knowledge should be easily available and understood by all. We believe passionately in the power of knowledge to change attitudes, perspectives, and to inspire people to act in ways that accelerate the world’s growth into a more fair and equitable place.

The Global Health Debates aim to illustrate how issues in public health affect every aspect of day-to-day life. This video series aims to inform and engage the public about issues related to climate change, migration, transnational corporations and decolonisation through discussions with expert panellists. Each debate will define the relevant topics, highlight the latest developments in the field, and aim to underscore the importance of taking action to cause positive change by leaving the audience with actionable take-home points.

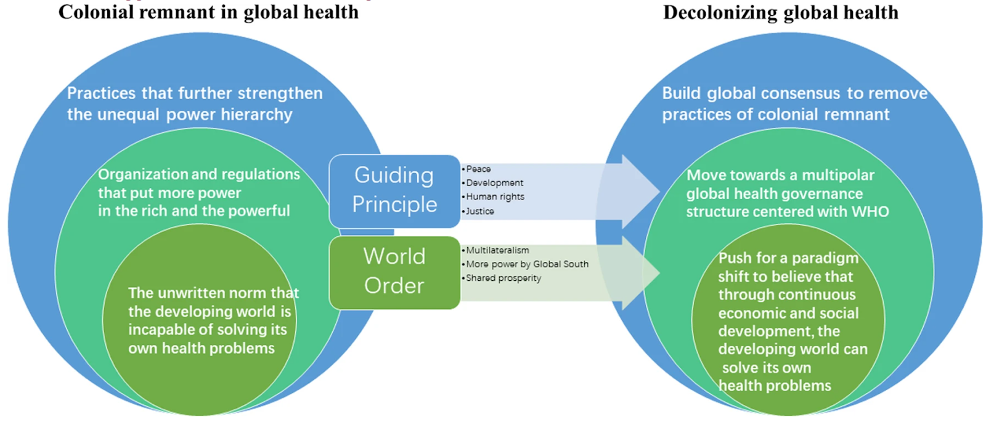

Our global health system is currently inequitable, hierarchical and filled with power imbalances throughout. These imbalances are the vestiges of colonialism – a broad, all-encompassing term that includes racism, anti-blackness, anti-indigenousness, tribalism, redlining, environmental injustices and the predatory nature of capitalistic practices.1 Unfortunately, this is not a historical practice that has been left in the past as a more mild version continues to exist known as neocolonialism.2 Thus, great power asymmetries continue to exist, and the objectives of both medical practice and research are built to protect the interests of the colonisers, often at the expense of the colonised.3 This influences all parts of the global health system including decision making, priority setting, and provision of funds.4

We must adapt and change our medical system to ensure that the 21st-century demands of equity and justice are being met.3 This can only be done by completely dismantling the remnants of colonialist practices that we continue to uphold, either intentionally or unintentionally. We need drastic change because our current system fails to properly understand and address the needs of low and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 This has resulted in many structured inequalities that predominantly affect racial and ethnic minority communities.3 Because colonialist tendencies have been around for so long, they are deeply embedded within the design of our healthcare system and affect everything, including our approach to partnerships.1 So the only way this process of decolonisation can begin is if we reflect deeply on how historical practices and perceptions are still guiding our decisions today.

The principle aim of decolonisation, defined as the state-sponsored deconstruction of non-merit inequalities, is to return power to LMICs to confer true equity and justice. (this definition was from the panelists, but we can find a reference for this if needed) This includes realigning the mission statements of large organisations to better reflect the needs of LMICs. Fundamentally, we need to change who sits at the table. We must ensure that the loudest voices must be the ones who have historically been marginalised. Simply put, decisions for the Global South must be made primarily by those from the Global South. Representation from this region needs to be increased, and leaders from this region need to be empowered to take more ownership.5 Ideally, we’d like to see more representative leadership throughout the entire global health system – from policymakers to editors of academic journals to healthcare educators. This will create a true bilateral flow of knowledge with reciprocal academic contributions from the Global North and South.1

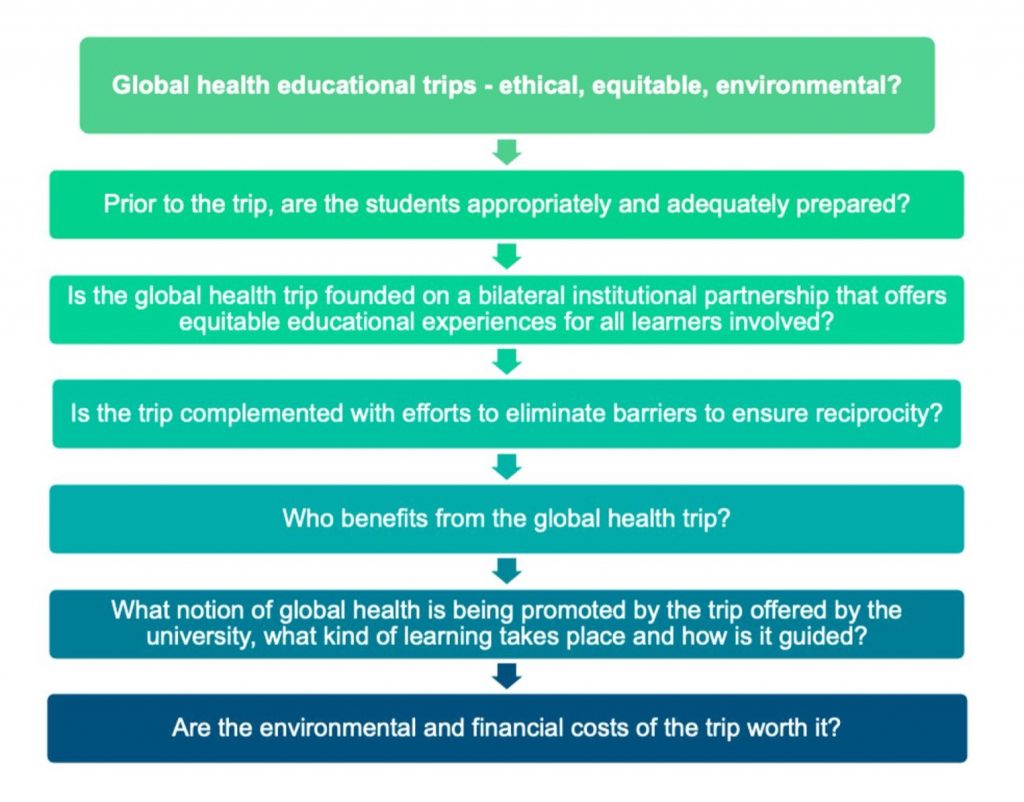

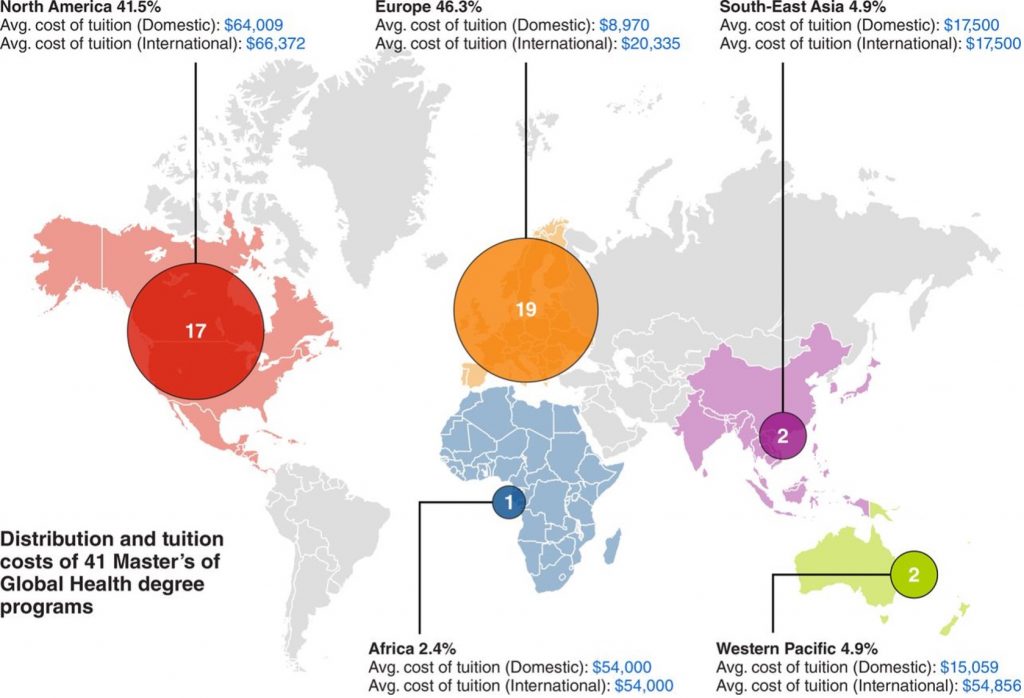

A growing push to decolonise public health is being led by students and other professionals who are demanding global health practitioners and institutions meaningfully address the impact of colonialism. The entire medical education system needs a revamp to deal with our new pressured reality, including the climate crisis. Part of this push includes modernising global health curricula and programmes in medical education to better reflect the goals of equity and justice globally.6 We must also challenge the narrative that the “West is best” in medicine, focusing on Western patients and allopathic medicine alone. (from panelist discussion, should be cite the speaker?) Thus, moving forward, we must clarify and codify the role of medical schools in teaching decolonising practices and raising awareness of structural inequalities.6 For example, this process may involve moving away from international medical elections. Often, these rotations are carried out in LMICs that perpetuate imbalanced power dynamics between host and sending institutions.7 Instead, better ways of democratising education include hosting more conferences in LMICs, creating more educational centres outside of high-income countries to encourage meaningful fieldwork, and making medical/scientific texts available in more languages.5

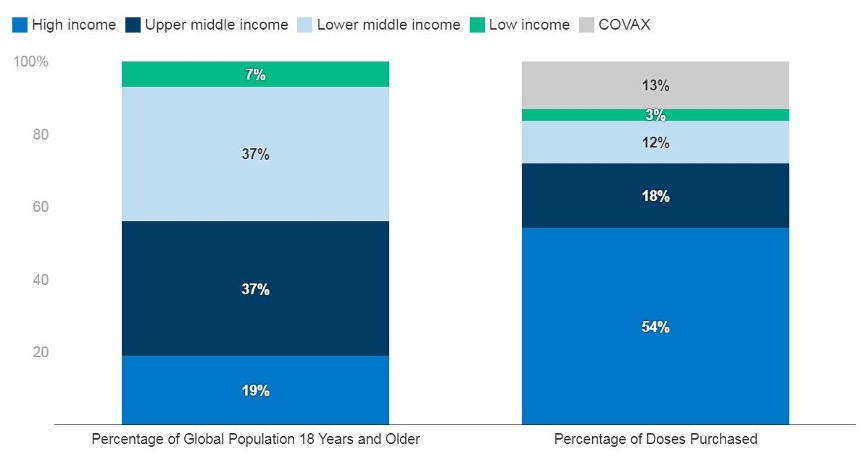

Recently, Covid-19 revealed that the global political economy was ill-equipped to handle a pandemic. This was best illustrated by the inequity in vaccine distributions, with most of the dosages having been delivered to the old colonial powers.8 This was deliberate as some countries (and companies) used their existing economic power to monopolise the vaccine supply chain for profits.9 These same entities were able to flex their political influence by constructing intellectual property barriers to prevent LMICs from producing vaccines even though they had the requisite laboratory capacity.10 Thus, existing colonialist constructs resulted in a lack of global sharing, collaboration and coordination.11 This was a disservice to all people as the health of one nation is inextricably linked to the health of another nation.

In conclusion, to push the decolonising movement forward, we must continue to highlight injustices. Moreover, we can use the rising popularity of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and the growing prevalence of Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) groups to increase visibility and awareness as these groups have synergistic goals to the decolonising global health movement.12,13 While the process of decolonisation begins with institutions, we must also hold ourselves, our colleagues and our discipline accountable by considering the indigenous ideology that we are connected – we must “wake up” and think about group responsibility and group outcomes to create a more equitable, just, and fair medical system that truly serves us all.

Figure 1. Tiered Levels of Colonial Remnant in Global Health14

Figure 2. Questions to ask about Global Health Educational Trips15

Figure 3. Distribution and Cost of Higher Education Programs in Global Health16

Figure 4. Power and Privilege amongst CEOs in Global Health17

Figure 5. Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution Inequality18

The author has no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge Mr. Sasha Chanoff, Dr. Abiodun Olaiya Paul, Ms. Susannah Sirkin for their participation as panelists in The Global Health Debates: The Migration Crisis and Social Unrest, which made this project possible. We also acknowledge the valuable contributions of our Producer, Dr. Circe Gray Le Compte, and Associate Producers, Ms. Dayana Bray, Mr. Sid Gugale, Ms. Lindsay Moore Murphy, Dr. Isioma Okolo, Dr. Dina Tadros, and Ms. Rebecca Yang, who contributed to the initial focus group on the migration crisis and social unrest.

Dr. Matthews is a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Fellow in Emergency Medicine, passionate about global health, equity and human rights. Her research interests include developing global health education, migrant health, mental health, elderly health, medical ethics, and law. She is also Executive Producer of the Great Health Debates. Dr. Matthews has long advocated integrating components of global health education into medical school curricula.

Dr. Carpenter serves as Co-Editor-in-Chief of HPHR Journal, and is Founder and Co-CEO of The Boston Public Congress of Public Health. She is also Executive Producer of the Great Health Debates. She is a neurosurgeon-in-training, bio and social entrepreneur, educator, and social justice advocate.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.