Matthews N, Carpenter C. Increasing migration in the 21st century: a burden or boom for nations?. HPHR. 2022;68.

The Global Health Debates is a video series aimed to democratise knowledge of complex global and public health topics into accessible summaries for a diverse audience. We believe that the world’s knowledge should be easily available and understood by all. We believe passionately in the power of knowledge to change attitudes, perspectives, and to inspire people to act in ways that accelerate the world’s growth into a more fair and equitable place.

The Global Health Debates aim to illustrate how issues in public health affect every aspect of day-to-day life. This video series aims to inform and engage the public about issues related to climate change, migration, transnational corporations and decolonisation through discussions with expert panellists. Each debate will define the relevant topics, highlight the latest developments in the field, and aim to underscore the importance of taking action to cause positive change by leaving the audience with actionable take-home points.

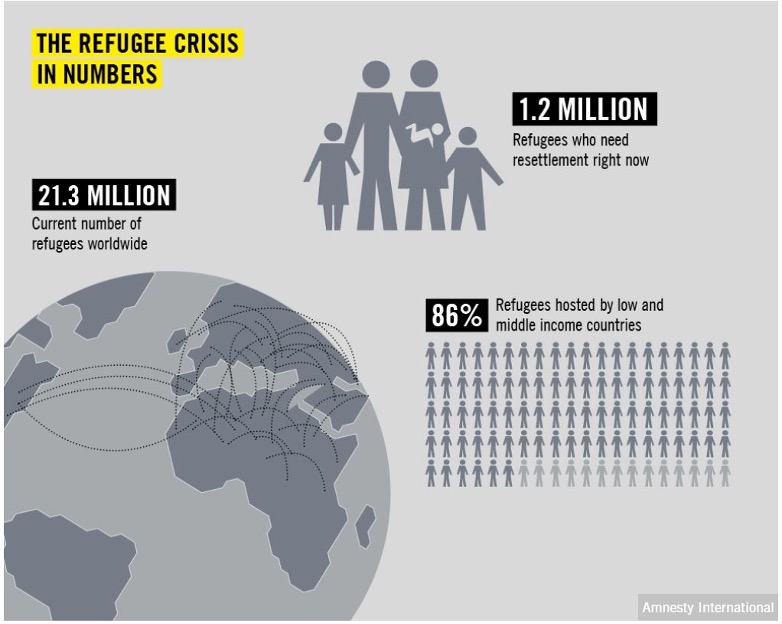

In today’s increasingly globalised world, the movement of people – or migration – has significantly increased. Currently, there are over 244 million international migrants, and international migrants make up 10% of the entire WHO European Region’s population.1 While people can move for many reasons, including better educational and economic opportunities, 70.8 million people were displaced due to violence, conflicts, and human rights violations.This number has doubled since the year 2000.2 Many of these people are given the designation of refugee, a legally different designation from being a migrant.3 This is an important distinction to note as misappropriating terms can lead to serious inequalities. Over 67% of all refugees come from just five countries, including Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar and Somalia.2

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), not all countries are doing their fair share to accept migrants and refugees. In fact, about 73% of refugees end up in a neighbouring country.4 This creates a disproportionate burden on some nations as only 16% of the total refugee population is hosted in countries considered “rich and developed.” Currently, there are over 1.4 million refugees in need of immediate resettlement; however, merely 90,000 were resettled in 2018.2 While camps are meant to provide temporary residence, many refugees end up spending years in them as they face significant hurdles in resettling.5 With about half the refugee population under the age of 18, this creates substantial limitations in educational and future employment opportunities.6 It is also important to note that seeking asylum is never a crime. This right is enshrined in Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.7

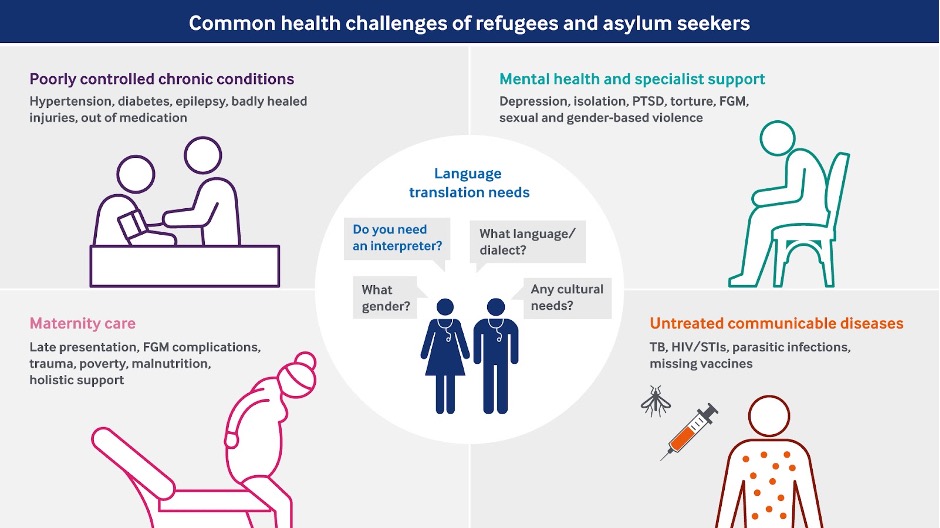

Migrants also face many barriers in accessing health. According to the WHO, these include limited access due to legal status, a shortage of interpreters and a lack of guidance on accessing healthcare.3 Migration itself is considered a social determinant of health and is associated with poorer health outcomes, most commonly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mood disorders, and depression.3,8

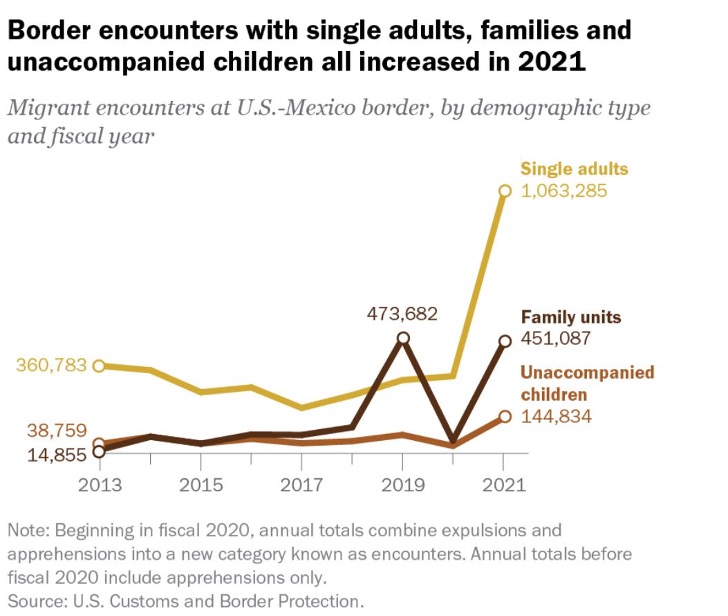

All of these contextual factors have led to a migrant crisis. Currently, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has resulted in one of the largest population displacements, with over 4.7 million people fleeing from Ukraine to mainly Poland, Germany, Romania, and Hungary.9 Similarly, in the United States, there continues to be a steady influx of migrants from the southern border, with border patrol reporting 1.7 million encounters last year.10

In light of this, the role and effect of migrants on society is still debated. Many have demonised migrants by linking their arrival to the rise of nationalistic political movements in Europe and the US.11 The past two Presidential administrations have detained migrants at the southern border and placed them infamously in cages.12 Despite strong anti-migrant sentiments in some parts of the world, much progress has been made. The Marrakech Compact in the EU created a solid framework to increase international corporation for accepting more

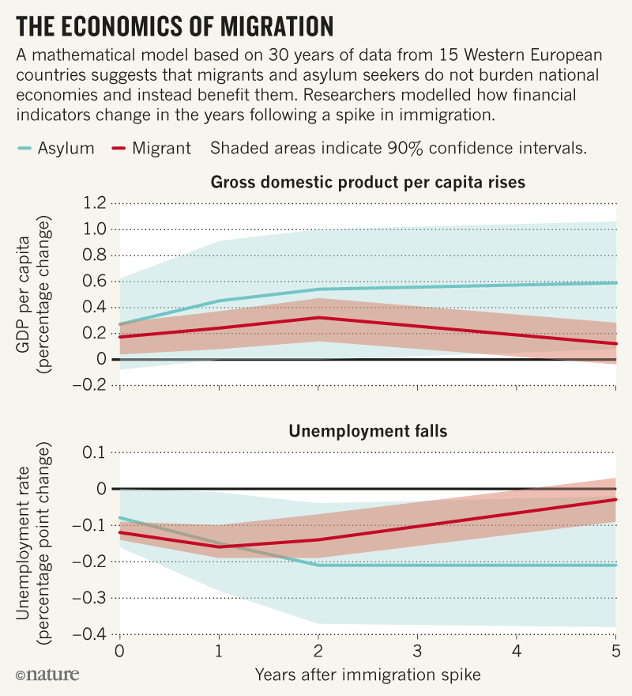

migrants/refugees.13 President Biden has doubled the refugee cap to 125,000 for 2022 and vowed to protect 7 million unauthorised immigrants from deportation.14,15 Overall, migrants contribute socially and economically by improving labour shortages, paying taxes, and enriching the intellectual and cultural zeitgeist.16

Overall, the migration crisis will continue to persist as long as borders are omnipresent; and, despite being artificially created and a vestige of colonialism, borders are unlikely to be abolished as they serve as a necessary means of organisation and control at the international level.17 Given the scope and breadth of the migration crisis, it is clear that the humanitarian system needs major reforms. First, refugees should be granted asylum status after an adjudication process that is more fair, expeditious and timely.18 Moreover, as refugees are increasingly permanently, not temporarily, settling in camps, we must ensure that there are pathways for them to integrate into society.19 These include labour mobility programs that offer employment in the local economies.20,21 We must continue to uphold the four pillars of the Global Compact on Refugees affirmed by the United Nations General Assembly: ease the pressures on host countries; enhance refugee self-reliance; expand access to third-country solutions; support conditions in countries of origin for return in safety and dignity.22 Overall, while we may not be able to migrate the factors that directly lead to migration – such as armed conflict, lack of resources and extreme poverty, increasing climate threats – we must ensure that a universal and just system exists to provide all people with a safe place to stay while maintaining their personal liberties to a life with dignity, respect and self-determination.7

Figure 1. Refugee Crisis Summarised in Numbers23

Figure 2. Top Ten Countries with the Most Refugees23

Figure 3. Common Health Challenges of Refugees and Asylum Seekers24

Figure 4. US Border Encounter Increases by Type25

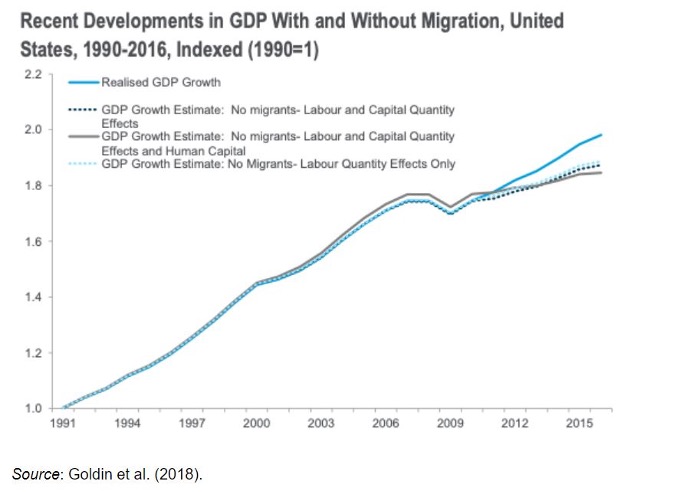

Figure 5. The Effects of Migration on Economic26

Figure 6. Effects of Migration on GDP27

The author has no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge Mr. Sasha Chanoff, Dr. Abiodun Olaiya Paul, Ms. Susannah Sirkin for their participation as panelists in The Global Health Debates: The Migration Crisis and Social Unrest, which made this project possible. We also acknowledge the valuable contributions of our Producer, Dr. Circe Gray Le Compte, and Associate Producers, Ms. Dayana Bray, Mr. Sid Gugale, Ms. Lindsay Moore Murphy, Dr. Isioma Okolo, Dr. Dina Tadros, and Ms. Rebecca Yang, who contributed to the initial focus group on the migration crisis and social unrest.

Dr. Matthews is a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Fellow in Emergency Medicine, passionate about global health, equity and human rights. Her research interests include developing global health education, migrant health, mental health, elderly health, medical ethics, and law. She is also Executive Producer of the Great Health Debates. Dr. Matthews has long advocated integrating components of global health education into medical school curricula.

Dr. Carpenter serves as Co-Editor-in-Chief of HPHR Journal, and is Founder and Co-CEO of The Boston Public Congress of Public Health. She is also Executive Producer of the Great Health Debates. She is a neurosurgeon-in-training, bio and social entrepreneur, educator, and social justice advocate.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.