Jones E and Malone S. Mortality trends in heart disease in Mississippi, 2010-2021. HPHR. 2024;64. 10.54111/0001/LLL4

Due to the lack of studies examining heart disease mortality trends and its implications on health in populations significantly affected by heart disease, this study aimed to address the gap in research and to identify the magnitude and the impact of heart disease mortality by exploring trends in heart disease mortality among Mississippians from 2010 to 2021.

The study uses data from the Mississippi Statistically Automated Health Resource System, which is an online database with data collected from vital statistics. Standard Error for the data was calculated using SAS. Overall and age adjusted mortality rates were calculated by gender, race, and age. Joinpoint regression models were used to calculate Annual Percentage Change (APC) and Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC) as an indicator of trends. The Joinpoint regression models were generated using independent and dependent variables, and standard error for gender, race, and age.

The overall age-adjusted mortality rate increased from 251.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2010 to 255.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2021 (1.5% increase). Comparisons between genders reveal an upward trend of heart disease mortality (AAPC, 0.71%- Males and AAPC, 0.08%- Females), and an upward trend of heart disease mortality among races (AAPC, 0.43%-blacks, AAPC, 0.38%- whites, AAPC, 3.68% -other). However, there was a declining trend in adults 65 years and older (AAPC, -0.16%).

This study identified an overall increase in heart disease mortality. However, trends varied by gender, race, and age. Based on study findings, Mississippi needs more initiatives aimed towards reducing heart disease mortality, specifically targeting blacks, males, and individuals under 65 years of age. This finding also demonstrates the effectiveness of other initiatives, within the state, such as the American Heart Association’s Go Red Campaign for women but reveals the need for more focus on the most at-risk groups identified within the study.

Heart disease mortality is a significant global issue that affects communities throughout the world.1 Globally, heart disease mortality is the leading cause of death and takes the lives of 17.9 million people each year, globally.2 In 2017, heart disease mortality was the leading cause of death in Mississippi.3 Heart disease mortality distributions and patterns highlight major health disparities based on race, age, and sex.4-6 Among the 695,000 heart disease deaths in the United States, 22.6% occurred in blacks, and 80% occurred in adults older than 65 years.7

Various epidemiological studies have shown a decline in heart disease mortality in recent years.8-9 However, Mississippi’s heart disease mortality rates are almost double national rates. In 2021, there were 173.8 heart disease deaths per 100,000 in the United States and 324.4 heart disease deaths per 100,000 in Mississippi.10 Examining trends in heart disease mortality based on gender, race, and age is important and serves as a tool to inform policy makers, and communities about the risk of heart disease mortality. Despite the importance of the topic, few studies have examined trends in heart disease mortality in Mississippi. To address the gap in research, this study explored the annual percentage change, and average annual percentage change in age adjusted heart disease mortality among Mississippians from 2010 to 2021.

Data was exported from the Mississippi Statistically Automated Health Resource System (MSTAHRS). The database contains heart disease related surveillance data from Mississippi. Both the calculation of standard error in SAS Studio and the preparation of MS Excel/ text files were used to create mortality models and trends in Joinpoint Regression software. Stratification was used to separate the sample into subgroups (gender, race, age groups).11

Age-adjusted rates, and frequencies were extracted from the MSTAHRS. Standard error was calculated using SAS Studio. The Annual Percentage Change (APC) and Average Annual Percentage (AAPC) of mortality rates in various subgroups were calculated using U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Joinpoint regression program version 5.0.12 Joinpoint regression describes trends and significant changes in trends.

Based on the Bayesian information criterion, the Empirical Quantile Method was used to identify the significant best fit line for trend 1 and trend 2.13 P-value was not calculated based on the method. However, each model tested for significance and listed the results for significance. Confidence intervals were calculated for APC and AAPC.

Age-adjusted mortality is the rate of deaths in a population regardless of age. Increases and decreases in age-adjusted mortality signify that deaths in a population have increased or decreased regardless of age. Age-adjusted mortality rates were used in this study because using age adjusted rates reduce the risk of bias.

Annual percentage change (APC) and average annual percentage change (AAPC) are statistical tools used in Joinpoint regression, which is used for assessing statistical trends. Annual percentage change (APC) is used to depict the change within a segment of the years of the study. The average annual percentage change (AAPC) is used to depict the change within the total years of the study. A significant APC and/or AAPC means that there is a valid change in the trend that is being evaluated. APC and AAPC were selected as a statistical approach for this study because Joinpoint regression is a more thorough means of identifying trends using reliable models.

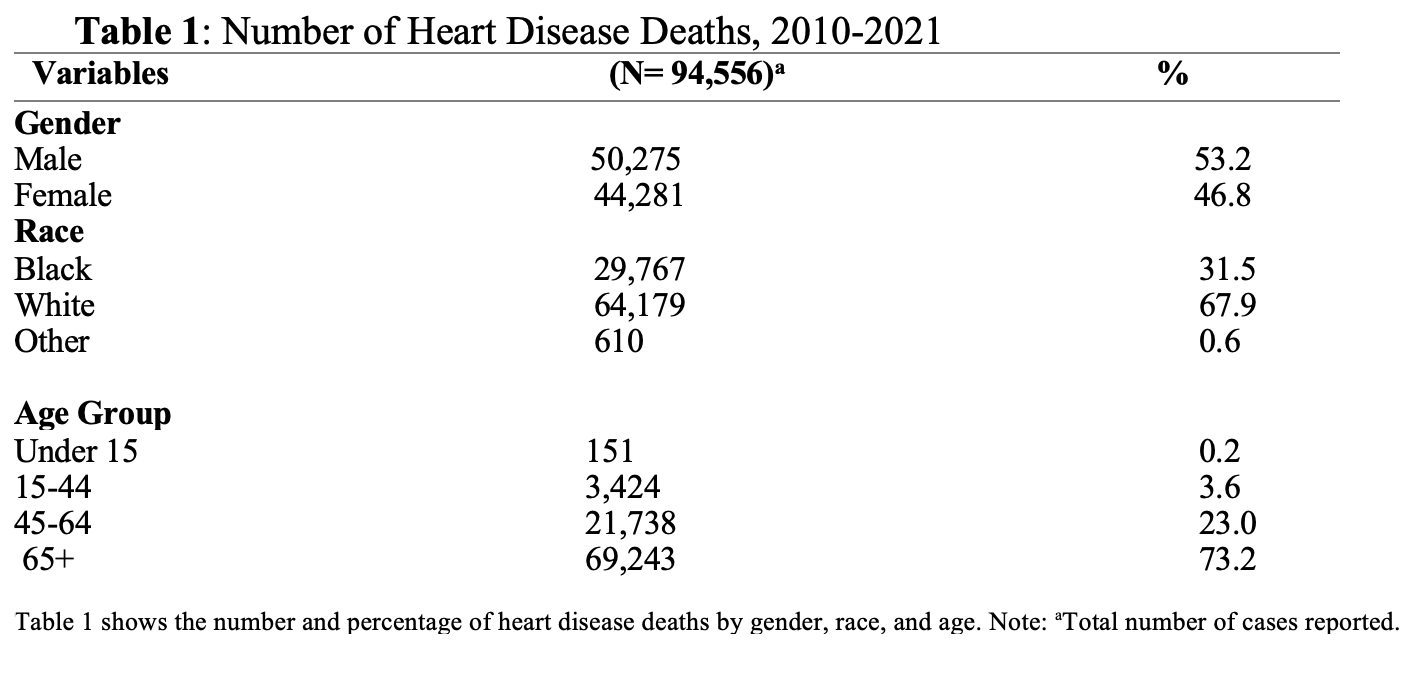

Between 2010 to 2021, Mississippi had a total of 94,556 deaths from heart disease. The source population for mortality rates were approximated from 2010 to 2021 and was obtained from Mississippi vital statistics. Majority of the cases occurred in males (53.2%), whites (67.9%), and age group 65 and older (73.2%) (Table 1). The overall age-adjusted mortality rate increased from 251.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2010 to 255.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2021 (1.5% increase) (Table 1).

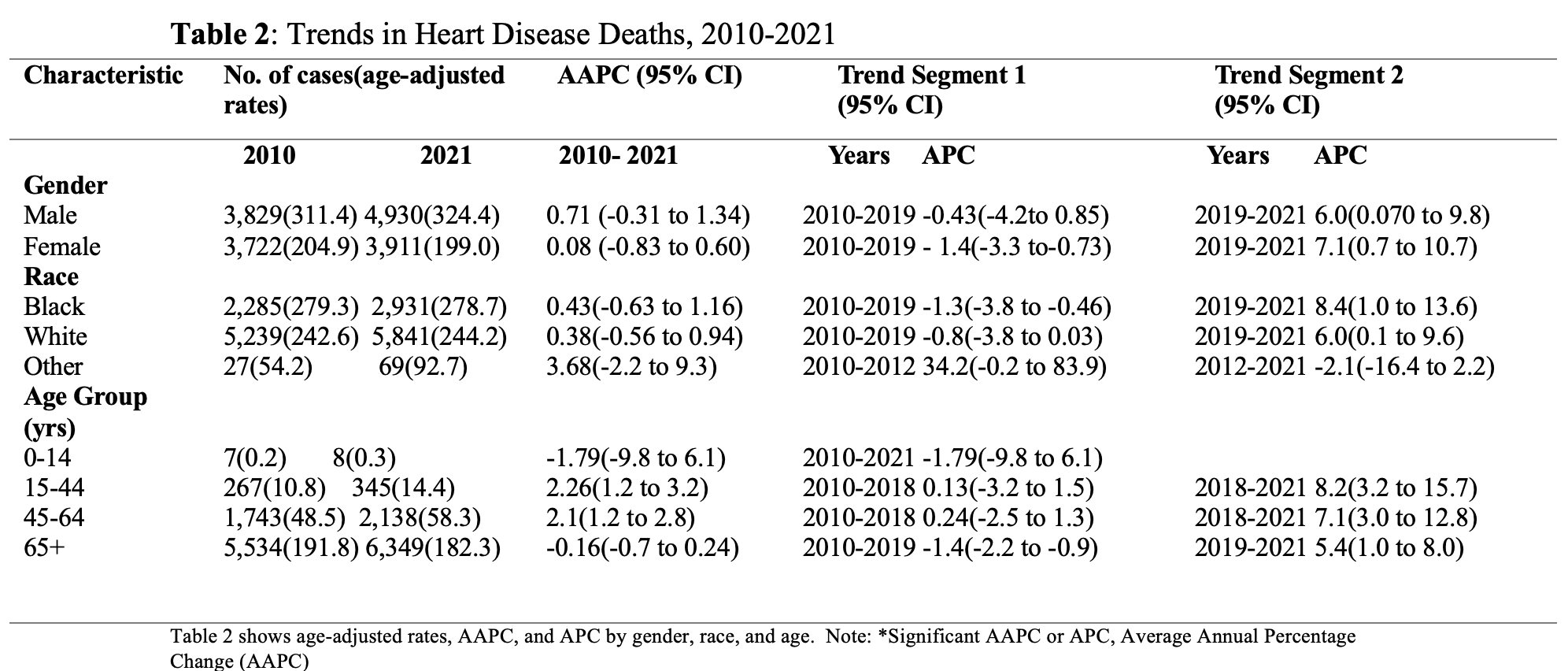

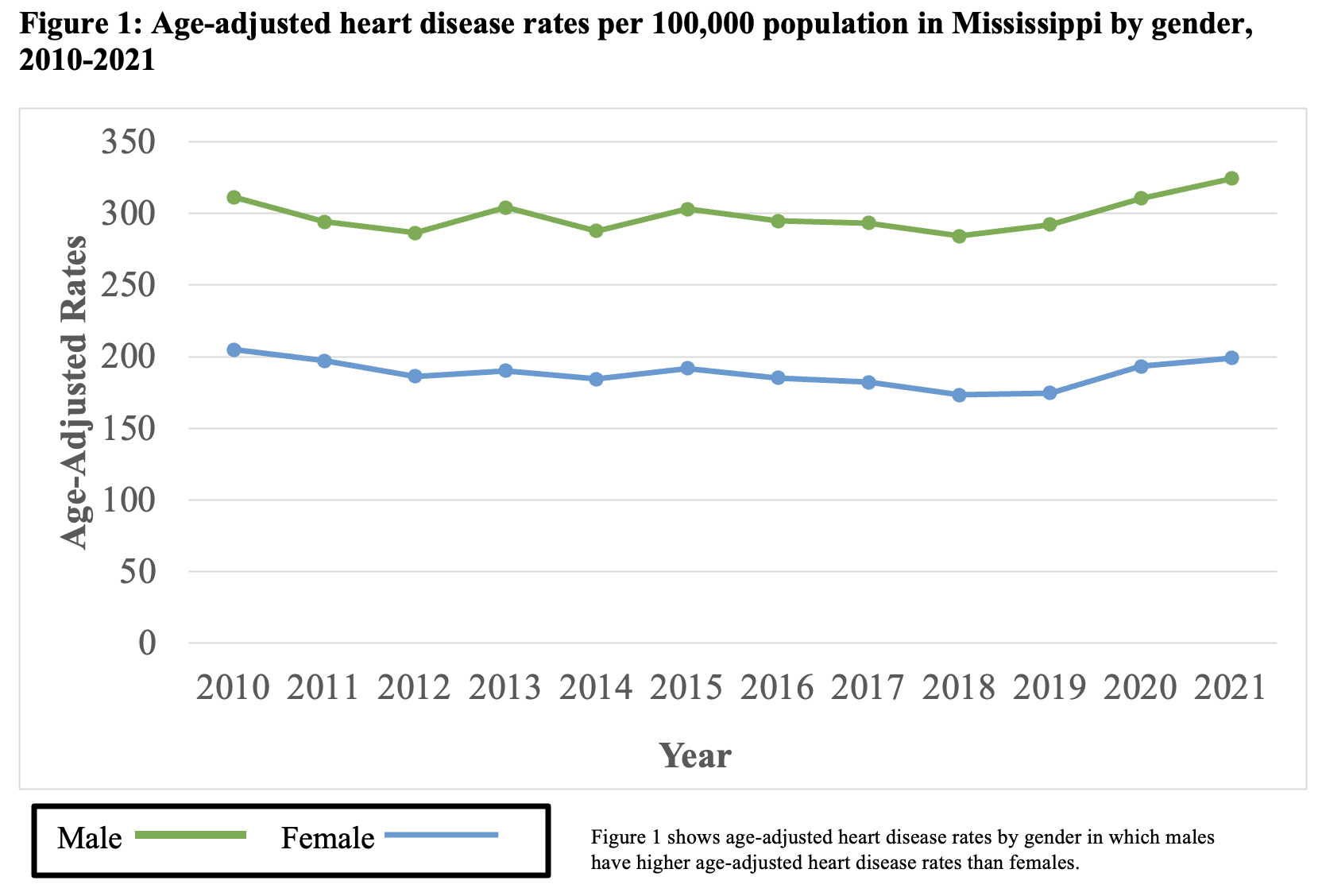

From 2010 to 2021, the age-adjusted mortality rate among males increased by 4% (311.4 deaths per 100,000 to 324.4 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 0.71% (AAPC, 0.71%, 95% CI, -0.31% to 1.34%). The age-adjusted mortality rate among females decreased by 2.9% (204.9 deaths per 100,000 to 199.0 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 0.08% (AAPC, 0.08%, 95% CI, -0.83% to 0.60%). (Table 2) (Figure 1)

The trends in males consisted of 2 segments: a significant APC of -0.43% (95% CI, -4.2% to 0.85%) in the first segment (2010-2019), and a significant APC of 6.0% (95 CI, 0.070% to 9.8%) in the second segment (2019-2021). The trends in females consisted of 2 segments: a significant APC of -1.4% (95% CI, -3.3% to -0.73%) in the first segment (2010-2019), and a significant APC of 7.1% (95% CI, 0.7% to 10.7%) in the second segment (2019-2021). (Table 2)

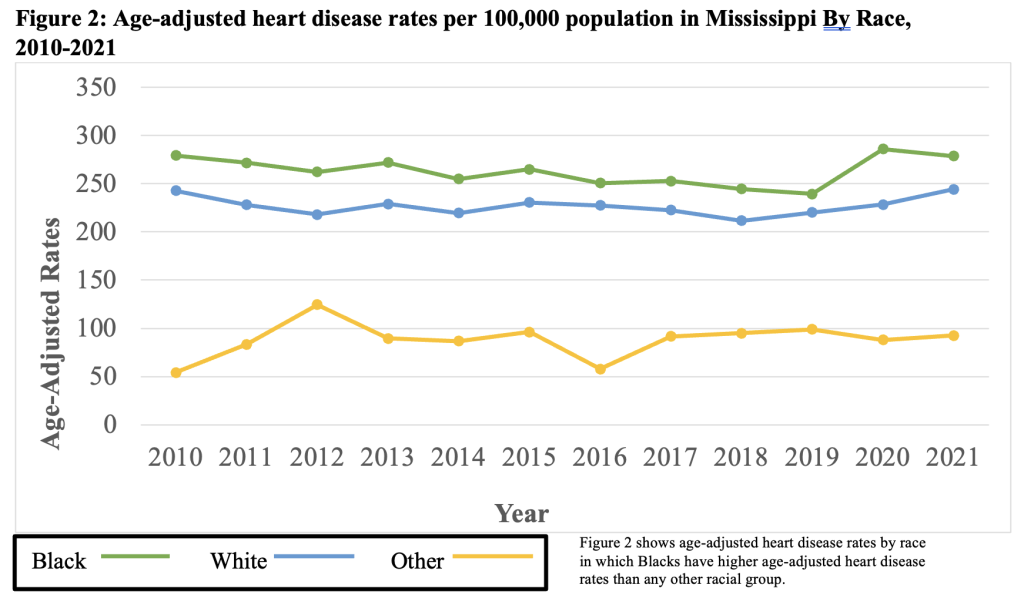

From 2010 to 2021, the age-adjusted mortality rate among blacks declined by 0.2% (279.3 deaths per 100,000 to 278.7 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 0.43% (AAPC, 0.43%, 95% CI, -0.63% to 1.16%). The age-adjusted mortality rate among whites increased by 0.7% (242.6 deaths per 100,000 to 244.2 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 0.38% (AAPC, 0.38%, 95% CI, -0.56% to 0.94%). The age-adjusted mortality rate among other races increased by 41.5% (54.2 deaths per 100,000 to 92.7 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 3.68% (AAPC, 3.68%, 95% CI, -2.2% to 9.3%). (Table 2) (Figure 2)

The trends in blacks consisted of 2 segments; a significant APC of -1.3% (95% CI, -3.8% to -0.46%) in the first segment (2010-2019), and a significant APC of 8.4% (95 CI, 1.0% to 13.6%) in the second segment (2019-2021). The trends in whites consisted of 2 segments; a significant APC of -0.8% (95% CI, -3.8% to 0.03%) in the first segment (2010-2019), and a significant APC of 6.0% (95% CI, 0.1% to 9.6%) in the second segment (2019-2021). The trends in other races consisted of 2 segments; a significant APC of 34.2% (95% CI, -0.2% to 83.9%) in the first segment (2010-2012), and a significant APC of -2.1% (95% CI, -16.4% to 2.2%) in the second segment (2012-2021). (Table 2)

From 2010 to 2021, the age-adjusted mortality rate among the 0-14 years age group increased by 33.3% (0.2 deaths per 100,000 to 0.3 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual decline of -1.79% (AAPC, -1.79%%, 95% CI, -9.8% to 6.1%). The age-adjusted mortality rate among the 15-44 years age group increased by 25% (10.8 deaths per 100,000 to 14.4 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 2.26% (AAPC, 2.26%, 95% CI, 1.2% to 3.2%). The age-adjusted mortality rate among the 45-64 years age group increased by 16.8% (48.5 deaths per 100,000 to 58.5 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual increase of 2.1% (AAPC, 2.1%, 95% CI, 1.2% to 2.8%). The age-adjusted mortality rate among the 65+ years age group declined by 4.9% (191.8 deaths per 100,000 to 182.3 deaths per 100,000), with an average annual decline of -0.16% (AAPC, -0.16%, 95% CI, -0.7% to 0.24%). (Table 2)

The trends in ages 0-14 years consisted of 1 segment; a significant APC of -1.79% (95% CI, -9.8% to 6.1%) in the first segment (2010-2021). The trends in ages 15-44 years consisted of 2 segments; a significant APC of 0.13% (95% CI, -3.2% to 1.5%) in the first segment (2010-2018), and a significant APC of 8.2% (95% CI, 3.2% to 15.7%) in the second segment (2018-2021). The trends in ages 45-64 years consisted of 2 segments; a significant APC of 0.24% (95% CI, -2.5% to 1.3%) in the first segment (2010-2018), and a significant APC of 7.1% (95% CI, 3.0% to 12.8%) in the second segment (2018-2021). The trends in ages 65 years and older consisted of 2 segments; a significant APC of -1.4% (95% CI, -2.2% to -0.9%) in the first segment (2010-2019), and a significant APC of 5.4% (95% CI, 1.0% to 8.0%) in the second segment (2019-2021). (Table 2)

Among all age groups, age adjusted heart disease mortality increased by 1.5% between 2010 and 2021. Age adjusted heart disease mortality was highest among males, blacks, and individuals 65 years and older. These findings are identical to national statistics regarding heart disease mortality.7 However, the direction of the trends for age adjusted mortality rates differ between Mississippi and the national average. There is an upward trend of heart disease mortality in Mississippi and a decreasing trend of heart disease mortality in the United States.14 These findings highlight a need for awareness, education, and health promotion among Mississippians to eliminate the risk of heart disease mortality. Medical practitioners and public health practitioners have attributed various risk factors to heart disease mortality, including smoking tobacco, drinking, obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, physical inactivity, poor diet, and secondhand smoke exposure.15 In Mississippi, the upward trend in heart disease mortality tends to be associated with an unhealthy lifestyle, dietary habits of the typical southern diet, which includes fried foods, foods high in sugar, and foods high in sodium, and lack of exercise.16

Furthermore, findings suggest a decrease in age adjusted heart disease mortality among females in Mississippi. These findings could be attributed to the Go Red Campaign organized by the American Heart Association of Mississippi. The campaign was launched in 2004, and has been implemented in colleges, local health departments, and various other spaces within the state. Female Mississippians have benefited from the effectiveness of the initiative to bring awareness to heart disease in women.

Based on the study findings, Mississippi needs more initiatives aimed towards reducing heart disease mortality, specifically targeting blacks, males, and individuals under 65 years of age. By creating initiatives targeting the most at-risk groups, Mississippi could tremendously benefit and improve health outcomes within the state. It would also allow Mississippi to possibly follow the declining trend of heart disease mortality in the United States.

This study has some limitations. First, only individuals with confirmed heart disease mortality were included in the study, which may have left out individuals with unconfirmed heart disease mortality due to comorbidities. Second, based on the nature of the study, there is a low capacity to estimate associations. Third, there is no way to identify confounding factors associated with heart disease mortality. Fourth, there is a limitation for the study’s timeframe due to the unavailability of data after 2021, which is why the study focused primarily on findings between 2010-2021. Finally, the analysis was only stratified by age, race, and sex due to the lack of data on other groups, such as LGBTQIA2S+ within the statewide database.

The major strength of this study was its’ use of surveillance data from Vital Statistics within the Mississippi State Department of Health. The study is also sound because it focuses on analyzing trends and changes over periods of time. The reports and data from the MSTAHRS database are reliable and consistent with findings in the United States.17 The results are also generalizable to Mississippi and other states within the southern region.17

From 2010-2021, there is an upward trend of heart disease mortality in Mississippi. Blacks, males, and individuals under 65 years of age have significantly higher heart disease mortality rates than any other race, gender, and age group. The habits, diet, and physical inactivity of individuals within southern states, such as Mississippi have greatly impacted health outcomes. Due to the significant impact of mortality, it is important that Mississippi initiates more programs that will promote healthy habits and lifestyle changes, educates communities, and brings awareness to heart disease mortality in the state to ensure that all Mississippians, especially at-risk groups are able to improve their health outcomes and reduce the risk of mortality.18 These findings also suggest the need for equity in the provision of cardiovascular healthcare services and prevention efforts. By addressing inequities in access to care, financial resources, employment, and gender inequities within prevention efforts due to the significant focus of cardiovascular health prevention efforts on Black women, heart disease mortality disparities within Black males under 65 years of age could be improved.19-21

The financial strain, hospital closures, implicit and explicit healthcare bias, and subpar employments options in the state are impacting health outcomes as a means of socially determining health. One major social determinant of health that is contributing to disparities in Mississippi is healthcare access, specifically the lack of insurance. 22 Counties in Mississippi with a higher prevalence of residents lacking insurance also have higher age-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases.22 The relationship between the risk of cardiovascular diseases and the lack of insurance is due the risk of health issues associated with not receiving regular outpatient care, increase risk of hospitalization, and declines in overall health.23 Findings also suggest a need for continuing to assess trends by comparing trends in insurance coverage and cardiovascular disease mortality in Mississippi by gender, race, and sex to identify and further understand disparities within specific groups. Therefore, the impact of heart disease mortality, the need for lifestyle changes, the need for prevention efforts, and the role of heart disease mortality inequities all play a role in heart disease mortality outcomes within the state and elicit a need for a strong and inclusive healthcare, public health response, and further statistical analyses.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Elizabeth Jones was born in Vicksburg, MS but has lived majority of her life in the Jackson, Mississippi area. Elizabeth has served as a CDC/CSTE Applied Epidemiology Fellow, a consultant, and as a researcher. She has a bachelor’s degree in sociology/pre-med from Tougaloo College. She also has a master’s degree in public health from Jackson State University. Currently, she is a DrPH student at Jackson State University. Elizabeth was also selected as a student marshal for the College of Health Sciences during the fall graduation ceremony at Jackson State University in 2020, selected as a plenary speaker for the 2nd International Webinar on Physical Health, Nursing Care, and COVID-19 Management, and as a guest lecturer for a CEAL Webinar Session held at the University of Southern Mississippi. She has published 4 articles with 3 articles as 1st author with the topics ranging from COVID-19/infectious diseases to sleep apnea. She also served as a reviewer for several journals and the American Public Health Association Conference and as a technical editor for the recently published book entitled, Epidemiology for Dummies. She is also an author of a book chapter entitled, Epidemiology of Childhood Sleep Apnea. Elizabeth is also an editorial board member for MED DOCS-Depression and Anxiety.

Dr. Shelia Malone obtained a doctorate in Public Health from Jackson State University. Her research has focused on health disparities in rural areas in Mississippi and nationally. She has worked to identify preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially, economically, and geographically disadvantaged populations. She hopes her research efforts will change the discourse on health equity and equality for rural Mississippians. Her other interests are centered on rural efficacy and diversity inclusion initiatives in health management. Shelia also has a Bachelor of Arts in Professional Interdisciplinary Studies and a Master of Science in Public Policy and Administration (Healthcare Administration), both from Jackson State University.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.