Haddad E, Hill B, Grant K, Henri S, Giffords H, Bareng M. A patient’s perceived effect of the “no visitor policy” implemented during COVID on their overall mental and physical health: A retrospective, observational study. HPHR. 2022;62. 10.54111/0001/JJJ3

A social support system has proven to improve patient outcomes; thus, we are proposing that with the implementation of the “No Visitor Policy” during COVID that there was an effect on the patient’s overall physical and mental health. Because this is a retrospective, observational study we assess the patient’s perceived level of effect that this “No Visitor Policy” had on their overall physical and mental health via a likert-style survey.

We conducted a retrospective, observational survey study in which we selected 538 participants in a random fashion via survey administration on social media. The Inclusion criteria were as follows: each participant must have been hospitalized with COVID during the pandemic as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as well as be located within the Windsor, Ontario, Canada area. Our primary outcome measurement is to determine whether the “No Visitor Policy” implemented during COVID impacted the patient’s overall physical and mental health.

The model consisted of 2 major themes; 57.81% of respondents indicating no perceived negative physical impact and 29.37% showing a minor negative physical impact, while 94.42% of the respondents perceived that their mental health was negatively impacted, with the majority of respondents, 32.16% indicating they felt the visitor restrictions had a major negative impact on their mental health. ANOVA statistical method identified a significant difference in perceived physical health between gender and whether their physical health was impacted; females (M=1.68, SD=.894) agree more than males (M=1.52, SD=.832) that their physical health was impacted. F (1, 536) = 3.452, p= 0.032. Furthermore, females (M=3.92, SD=1.079) agree more than males (M-3.47, SD=1.163) that their mental health was impacted F (1,536) = 0.748, p< 0.001).

We believe this is an important research topic to further investigate because patient outcomes and compliance are so closely tied with patient social support.

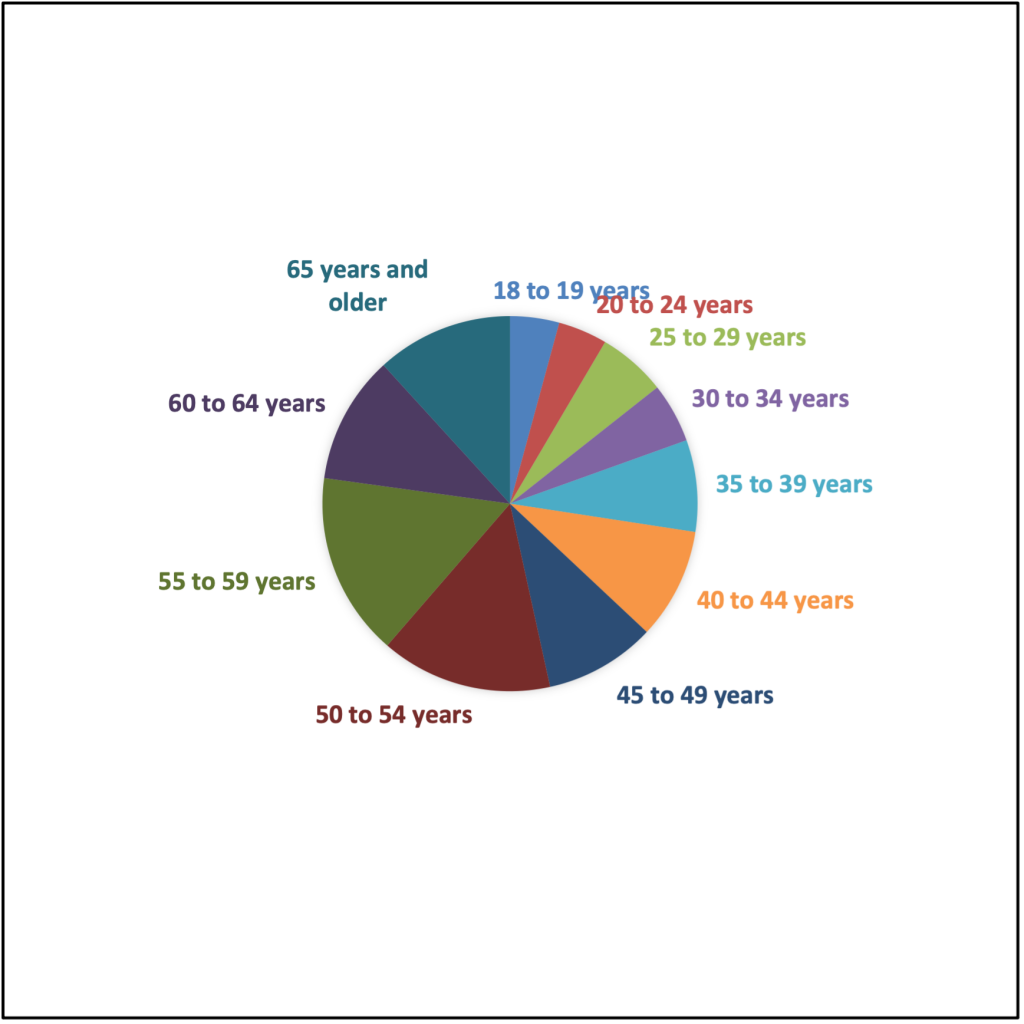

Using an observational retrospective design, qualifying participants completed a survey with a series of questions to assess the impact of the “No Visitor Policy” on their physical and mental health. Respondents were categorized using standardized age groups used by the census in Canada.

This study was conducted using the outlined survey (Appendix-I) using Survey Monkey via public local city pages (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) on social media outlets.

The population targeted patients over 18 years old hospitalized due to an acute illness in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, during December 2nd, 2020, and April 17th, 2021 (136 days). This geographical location was chosen due to its uniform hospital visitor restriction policies across all local hospitals, population size, and convenience of reach.

Using Slovin’s formula, the researchers estimated the number of respondents based on the population and statistical data regarding hospitalizations per month (Appendix-VI). Windsor, Ontario, Canada’s population and acute illness admission statistics, given the outlined timelines and a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, a total of 362 respondents were necessary.

A structured questionnaire was the primary tool in gathering data from the respondents. The first portion includes the demographic profile of the respondents, while the second portion includes the respondents’ experiences concerning their physical health and mental health. “No negative impact” will be categorized into “no impact group” and “Minor negative impact, “Moderate negative impact,” “Major negative impact,” and “Severe negative impact” will be grouped into “impacted group.”

Descriptive statistics was used to analyze the profile and impact of physical health and mental health as perceived by the patients over the age of 18 who were hospitalized due to an acute illness in Windsor, Ontario, Canada during December 2nd, 2020, and April 17th, 2021 (136 days).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the differences in the level of physical and mental health when grouped according to profile variables at 0.05 level of significance.

Pearson Product Moment of Correlation was used to determine the relationship between the age variable and levels of physical health and mental health of the respondents at 0.05 level of significance. A Chi-square test will be used to determine the relationship between the gender variable and levels of physical health and mental health of the respondents at a 0.05 level of significance.

Any respondent that did not meet the participation criteria, time, or geographical location criteria and any respondent that did not fully complete the survey questions were excluded.

Age Groups | Frequency | Percentage |

18 to 19 years | 23 | 4.28% |

20 to 24 years | 23 | 4.28% |

25 to 29 years | 32 | 5.95% |

30 to 34 years | 28 | 5.20% |

35 to 39 years | 43 | 7.99% |

40 to 44 years | 52 | 9.67% |

45 to 49 years | 52 | 9.67% |

50 to 54 years | 75 | 14.94% |

55 to 59 years | 86 | 15.99% |

60 to 64 years | 60 | 11.15% |

65 years and older | 64 | 11.90% |

Total | 538 | 100% |

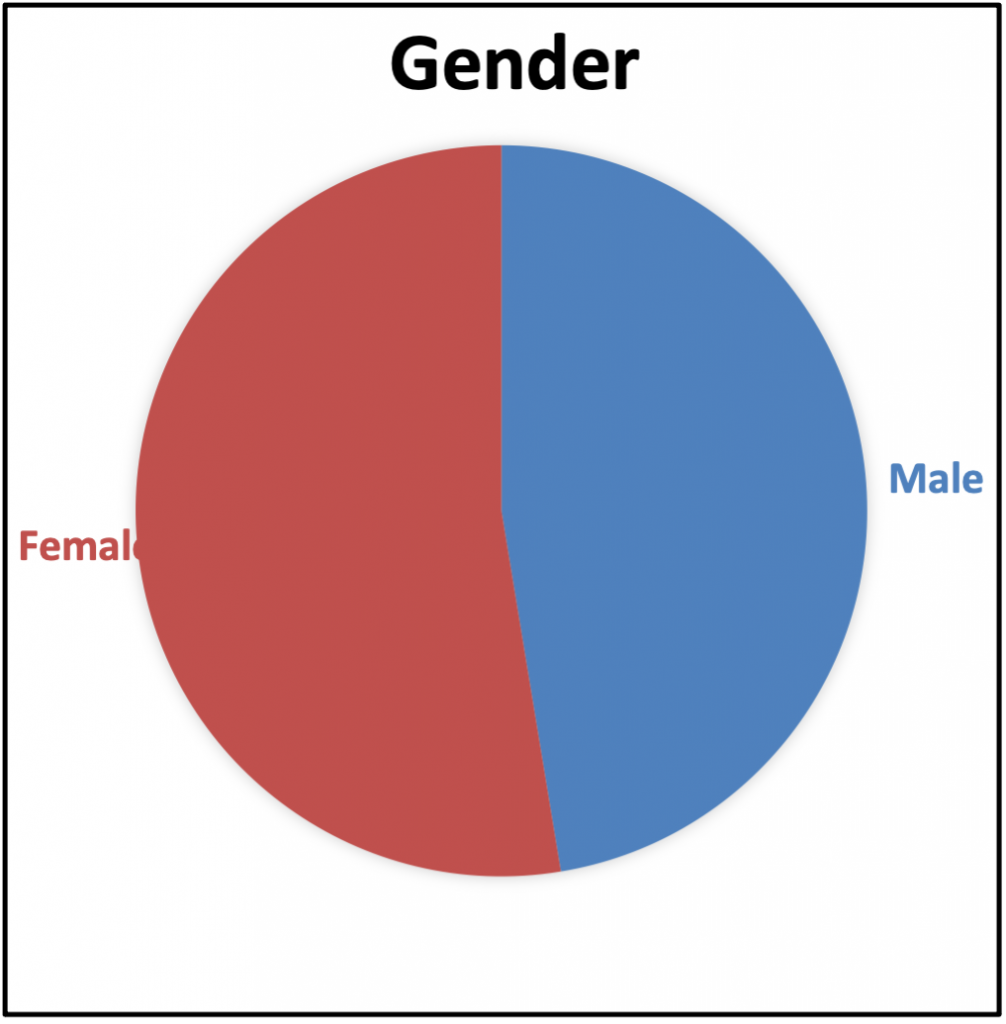

Gender | Frequency | Percentage |

Male | 255 | 47.40% |

Female | 283 | 52.60% |

Total | 538 | 100% |

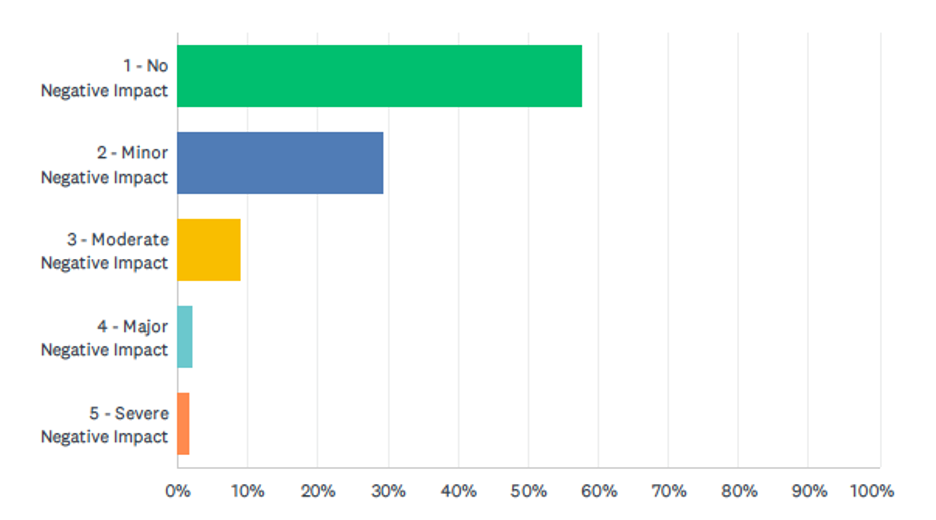

Description | Frequency | Percentage |

1 – No Negative Impact | 311 | 57.81% |

2 – Minor Negative Impact | 158 | 29.37% |

3 – Moderate Negative Impact | 48 | 8.92% |

4 – Major Negative Impact | 12 | 2.23% |

5 – Severe Negative Impact | 9 | 1.67% |

Total | 538 | 100 |

| |||||

Sources | df | SS | MS | F | p |

Between groups | 1 | 3.452 | 3.452 | 4.613 | .032* |

Within groups | 536 | 401.009 | .748 |

|

|

Total | 537 | 401.461 |

|

|

|

Note: * Significant at 0.05 | |||||

| |||||

Sources | df | SS | MS | F | p |

Between groups | 10 | 19.867 | 1.987 | 2.72 | .003** |

Within groups | 527 | 384.594 | .730 |

|

|

Total | 537 | 404.461 |

|

|

|

Note: ** Highly Significant at 0.01 | |||||

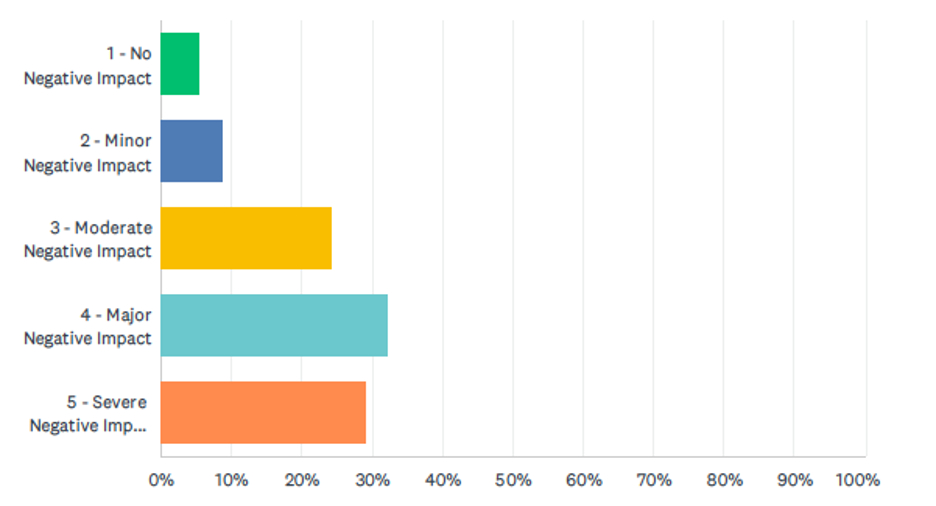

Description | Frequency | Percentage |

1 – No Negative Impact | 30 | 5.58% |

2 – Minor Negative Impact | 47 | 8.74% |

3 – Moderate Negative Impact | 131 | 24.35% |

4 – Major Negative Impact | 173 | 32.16% |

5 – Severe Negative Impact | 157 | 29.18% |

Total | 538 | 100 |

| |||||

Sources | df | SS | MS | F | p |

Between groups | 1 | 27.842 | 27.842 | 22.214 | .000** |

Within groups | 536 | 671.756 | 1.253 |

|

|

Total | 537 | 699.599 |

|

|

|

Note: ** Highly Significant at 0.01 | |||||

| |||||

Sources | df | SS | MS | F | p |

Between groups | 10 | 21.209 | 2.121 | 1.648 | .090NS |

Within groups | 527 | 678.389 | 1.287 |

|

|

Total | 537 | 699.599 |

|

|

|

Note: NS Not Significant | |||||

| |||

Variable | Age | Physical Health | Mental Health |

Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) | 1 | -.076 | -.016 |

| .080 NS | .716 NS | |

Note: NS Not Significant | |||

| |||

| Value | df | Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

Pearson Chi-Square | 6.541 | 4 | .162NS |

Note: NS Not Significant | |||

| |||

| Value | df | Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

Pearson Chi-Square | 29.299 | 4 | .000** |

Note: ** Highly Significant at 0.01 | |||

The power for this research project indicated that 362 surveys would be required for the results to be statistically significant. There was a total of 547 respondents that completed the survey. Of those 547 respondents, 9 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or did not complete the survey correctly, leaving 538 respondent participants. The respondents were relatively diverse, with participants ranging from 18 to over 65 years. The majority of the respondents were between 50 and 65 years and older (285, 53.98%, see Table 1). Additionally, the respondents had equal representation regarding gender, with slightly more female respondents than male (Females 283, 52.60% and male 255, 41.40%, see Table 2).

The patient’s experience during hospitalization has been a point of refinement for health services improvement. A likert-style survey was utilized and a model representing the patient’s perceived physical health impact emerged from the analysis (see Figure 3). The model consisted of 2 major themes (see Table3), with approximately 57.81% of respondents indicating no perceived negative physical impact and 29.37% showing a minor negative physical impact.

ANOVA statistical method identified a significant difference in perceived physical health between gender and whether their physical health was impacted (see Table 4, Appendix II). Females (M=1.68, SD=.894) agree more than males (M=1.52, SD=.832) that their physical health was impacted. F (1, 536) = 3.452, p= 0.032. As the P-value is less than 0.05, this indicates the statistical significance and gives evidence against the null hypothesis. There is less than a 5% probability the null hypothesis is correct as of the result of randomization. Thus, we reject the null hypothesis. This finding indicates a definite and consequential relation between gender and perceived physical impact when visitors were limited, where females perceived more physical health impact than males. The overall results reveal that approximately 57.81% of respondents indicate no physical impact. In comparison, 42.19% of respondents indicate minor to severe negative impact, with only 1.67% of respondents indicating a severe negative physical impact. This was further analyzed (see Appendix IV) with 133 females indicating some form of perceived negative physical health impact, while only 94 males reported a negative physical health impact.

Additionally, statistical analysis was performed to evaluate the difference between age groups, and their perceived physical health was impacted (see Table 5, Appendix III). The ANOVA statistical method identified a highly significant difference between age and physical health impact. Those in the age groups from 18 to 19 years old (M=2.17, SD = 1.193) agree more than those from 30 to 34 years old (M=1.39, SD=0.629). According to data collected, the order of age and physical impact from age groups with highest perceived physical impact to least perceived physical impact is as follows: 18 to 19 years old (M=2.17, SD = 1.193) with highest perceived physical impact, 20 to 24 years old (M=2.00, SD=1.044), 65 years and older (M=1.83, SD=1.106), 35 to 39 years old (M=1.70, SD= 0.832), 25 to 29 years old (M=1.63, SD= 0.833), 40 to 44 years old (M=1.54, SD= 0.830), 60 to 64 years old (M= 1.53, SD= 0.700), 45 to 49 years old (M = 1.50 , SD= 0.754), 55 to 59 years old (M= 1.49, SD= 0.778), 50 to 54 years old (M=1.45, SD=0.810), 30 to 34 years old (M=1.39, SD=0.629) with least perceived physical impact. F (10,527) =2.722, p< .01. According to the p-value, we can reject the null hypothesis. The results provide support indicating a definite and consequential relationship between age group and perceived physical impact.

The ANOVA statistical method identified a significant difference in mental health between gender and whether their mental health was impacted (see Appendix II). Females (M=3.92, SD=1.079) agree more than males (M-3.47, SD=1.163) that their mental health was impacted. F (1,536) = 0.748, p< 0.001). According to the p-value, the researchers can reject the null hypothesis. Our results provide support indicating there is a definite and consequential relationship between gender and mental health impact. According to the data (see Table 6), approximately 94.42% of the respondents perceived that their mental health was negatively impacted, with the majority of respondents, 32.16% indicating they felt the visitor restrictions had a major negative impact on their mental health.

Statistical analysis was performed to evaluate the difference between age groups and their perceived mental health impact. Those in 20 to 24 years old (M=4.22, SD= 0.951) agree more than any other age group that their mental health was impacted. Those in the age groups from 30 to 34 (M=3.39, SD=1.286) agree that their mental health was impacted. F (10,527) = 1.648, p>.05. One- Way ANOVA data indicates no statistical difference between age groups and perceived mental health impact. Thus, for this relationship we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

A Pearson correlation was used to express how the two variables, age, and perceived physical impact, are linearly related (See Table 9). The data indicates no correlation between age and physical health, r (538) =-0.076, p> 0.05. However, the data is not statistically significant. Additionally, the correlation between age and mental health was also measured. The data indicates no correlation between age groups and perceived mental health impact, r (538) = 0.016, p >.05. The data is also not statistically significant. Thus, we fail to reject the null hypothesis for both a correlation between age and physical health and for age and mental health. The lack of evidence doesn’t prove that an effect does not exist.

A Chi-Square test was used to examine whether a statistically significant relationship exists between nominal and ordinal variables to determine whether two variables are independent of one another. We looked at whether gender and perceived physical health are independent or not (see Table 10, Appendix IV). The data indicates no relationship between gender and perceived physical health X2 (4, N=538) = 6.541, p>.05. There was no association between gender and perceived physical health. Thus, we fail to reject the null hypothesis, and our data did not provide sufficient evidence to conclude that an effect exists. We also examined the statistically significant relationship between gender and mental health (see Table 11, Appendix V). The data indicates, there is a significant relationship between gender and mental health X2 (4, N=538) = 29.299, p<.01. Thus, we reject the null hypothesis, indicating a relationship between gender and mental health.

The respondent age profile is outlined in Figure 1 and Table 1. Furthermore, the age distribution is outlined in Figure 2 and Table 2, with 47.4% (255) of respondents being male patients and 52.60% (283) female patients.

On the provided scale of 1-5, 1 being no negative impact on physical health and 5 indicating a severe negative impact on physical health, 57.81% (311) of respondents answered that they experienced no negative impact as a result of the “No Visitor Policy” which were put in place due to COVID-19 in Windsor, Ontario. 42.19% (227) reported negative impact; with 29.37% (158) minor negative impact and 1.67% (9) severe negative impact (see Figure 3 & Table 3).

Although more than 57% of the respondents answered, they experienced no physically negative impact, 43% of people did share some type of negative impact regarding their physical health and social isolation. Studies have shown that people with depression have worse outcomes in physical recovery.20.

Furthermore, with regards to mental health, the provided scale of 1-5, 1 being no negative impact and 5 being severe negative impact; 94.43% (508) were impacted; with 8.47% (47) with minor impact and 29.18% (157) being severely impacted (see Figure 4 and Table 4). Several studies have described mental health consequences in prior lockdowns, such as increased depression, stress, or insomnia.17 What was unknown was the mental state and capacity of the individuals that completed the survey for the study.8

Zavaleta et al. (2017) defined social isolation as “inadequate quality and quantity of social relations with other people at the individual, group, community, and larger social environment levels where human interaction takes place.”22 Policymakers and practitioners have realized the role those social relationships play with individuals. Structures through social connections can influence health.20 People with mental illness may have a more significant negative experience with isolation than the general population.

According to the results, there was a difference between gender and physical health. More females were impacted in their physical health than males; being a female was considered a risk factor.17

All age groups were negatively impacted in their physical health; however, the 18-19-year-old group was most affected. To isolate these young adults from their families and peers could introduce forms of depression and anxiety.1

There was a difference between gender and mental health, with women being more affected than men. Study results from China and Italy suggest that women are more vulnerable to stress than men.1

There is a difference in the relationship between females and physical and mental health. More females were negatively impacted in these categories than males. Women and young adults are more likely to experience depression and anxiety than other groups.8 One study found that at the beginning of lockdown, younger adults and women, and people with pre-existing mental health conditions reported higher levels of depression and stress.8

Biological processes in gender differences are not fully understood; however, some evidence shows that the changing hormones in women may be responsible for sensitivity to emotional stimuli.1 Along with greater brainstem activation in women and greater hippocampal activation in men may enhance their capacity to conceptualize fear.

This study aimed to understand the patient experience, paying particular attention to aspects of hospitalization visitation policy during COVID restrictions. Policy and practice related to visiting hours are of pressing concern and will continue to be an ever-changing aspect of medical healthcare, specifically when the fear of an epidemic or pandemic is of genuine concern. Following the reactions to Coronavirus of 2019, policies and practices related to visiting hours in healthcare settings have become pressing, with no evidence-based guideline to inform decision-makers regarding the best available method. These findings provide insight for leaders and hospital policy makers into patients’ perceived physical and mental health impact during a time of hospital stays. The challenge presented is to maintain positive health outcomes, especially when faced with the challenge of minimizing the spread of infections. It is best to be proactive. This study provides insight into the importance of patients’ perception of physical health and mental health to better implement policies that decrease negative impact while increasing positive effect on patients.

Quarantines should be as short as possible to minimize the stress and negative impact physically and mentally.17 Some recommendations to help with social isolation would be to strengthen social connection and cognitive stimulation.17

Due to the nature of this retrospective observational study and the limited resources, this study will not capture respondents who expired during their hospitalization. Further limitations in the study include the possibility of recall bias and selection bias. Efforts were made to decrease confounders within the study by formatting the survey in the form of scales and prolonged-time collecting data for three months, thus allowing for a larger sample size. However, human memory is imperfect; the participants were asked to recall specific details to collect dates, thus introducing “recall bias” as patients may not remember the facts accurately. Furthermore, the study subjects may not be representative of the population as participants who chose to answer the survey may be different from those who decided not to answer.

Furthermore, there were no clear-cut quantitative definitions of no impact to severe impact. Each individual participant has an internal gauge of this definition and so there is not really any standard to assess what is considered no impact for one patient and what is considered severe impact for another patient. To combat this the data separated the groups into no impact and impact thereby alleviating some of that statistical discrepancy.

In summary this study has determined that during times of acute illness a patient’s mental and physical health are needed for recovery. According to this preliminary data, when hospital visitations are restricted, interventions should be considered to minimize the impact on physical and mental health. Moreover, the findings should be extrapolated and considered by healthcare professionals in the future when formulating response plans to confront future catastrophic and/or pandemic-like events.

Many studies have indicated patient outcomes are directly linked to the patient’s social support. We believe that our data warrants further investigation into other patient populations in order to determine if there is a link between the “No Visitor Policy” implemented during COVID and a patient’s perceived mental and physical health. We also believe that more data could prove beneficial in the future with regards to policy implementation changes.

There was no funding required for this observational study.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

I am a current second year medical student at Saint James School Of Medicine Anguilla. I received a Bachelor of Science from the University of Windsor. I completed training in Medical Laboratory Science from St. Clair College. I not only manage the daily life of a medical student, but am also able to continue my work as a Medical Technologist at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan. I have worked as a Medical Technologist for the last seven years with a specialized focus in blood transfusion medicine. I am a current member of the American Medical Student Association. I look forward to advancing the field of medicine through innovation and research.

I am a current second year medical student at Saint James School Of Medicine Anguilla. I have had the opportunity to be involved in Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) for over 15 years and have special interest in the promising effects of HBOT management of patients with Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI). I hope to complete my residency in either Emergency Medicine (EM) or Internal Medicine (IM) with possible fellowship in HBOT. I have a special interest in research and hope to continue to find projects that will promote excellence and advancement within the medical community.

I am a current medical student at Saint James School Of Medicine Anguilla. I am concurrently completing a dual doctorate pathway which I will complete a Doctorate in Public Health along with my Medical Doctorate. I joined the United States Army at the age of 17 and served in Iraq. I served a total of 10 years in the United States Army. I am currently involved in the Student National Medical Association, Inc. (SNMA) where I am serve as the Diversity Research Chair. As the Diversity Research Chair for SNMA, our committees role is to focus on promoting support through investments and improving the amount and quality of research in those underrepresented minority areas through the eyes of those minority medical students. SNMA also focuses on promoting racial equality within the physician medical profession.

I am a current second year medical student at Saint James School Of Medicine Anguilla. I received a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology and Nursing. I also received a Master’s degree from Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Health Service Administration. I have always wanted to pursue a career in the medical field. I initially thought about applying to Dental school but after being exposed as an Emergency Room Nurse during the Pandemic, I felt a calling to apply to medical school. I received my Bachelor’s degree of Nursing from Mount Aloysius College and believe that because of that strong base in education, faith and learning I am better equipped and more well rounded as a physician in training during this pandemic and as a future practicing physician. I am also very interested in providing access to quality mental health care that respects people’ human rights and implementation of Emergency Medical Services to help health equity, while decreasing the existing health disparities.

I am a current medical student at Saint James School Of Medicine Anguilla. I currently practice Veterinary Medicine in Phoenix, Arizona. I received my Doctorate of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) from Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine. I have had the opportunity to experience the healthcare profession from a variety of different perspectives as I previously worked as a police officer for the NYPD and as a first responder firefighter with the New York Fire Department. On September 11th, 2001 I was part of the New York Fire Department first responders on scene. Those brave men and women will never be forgotten. Being there when the North Tower fell and observing the bravery of average everyday men and women is something that I will remember for a lifetime. I have continued a life of service both in Veterinarian Medicine and now as a medical student at Saint James School Of Medicine. I hope that everyone will remember all those great guys that lost their lives during 9/11 and that the path I have chosen will make them proud.

Dr. Melchor L Bareng is the current Dean of Student Affairs at Saint James School Of Medicine at the Anguilla campus. Dr. Melchor L Bareng has received two Master degrees as well as a PhD degree. Dr. Melchor L Bareng has a Master in Public Health – Infectious Diseases from James Lind Institute and a Master of Science in Public Health from Universita Telematica Internazionale UNINETTUNO. Dr. Bareng also has a Master of Science degree in Human Biology for which he graduated in 2008 from Cagayan State University. Dr. Bareng received his Doctor of Philosophy in 2012 from Cagayan State University. He also completed Post Graduate Course in Occupational Health and Safety at the University of the Philippines. He is currently an Associate Professor of Medicine at Saint James School of Medicine. His subject area of focus is Histology. He currently teaches Histology. Dr. Melchor L Bareng is also an instructor of research, statistics and methodology. He mentors current medical students and is a co-author on our current research project focusing on how the “No Visitor Policies” implemented during COVID have impacted the individual patient’s mental and physical health.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.