Hollo A, Kohlbeck S, Nimmer M, Levas M. Association between well-being and community assets in a cohortt of youth vitims of violence in an urban setting. 2022;58. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/GGG1

The primary purpose of this study is to determine if there is an association between proximity to protective community assets and youth well-being following exposure to violence.

This study is a retrospective data analysis using existing data from 471 participants in a violence intervention program. Street addresses of participants were mapped using ArcMap version 10.8.1 mapping software and a buffer analysis was conducted to determine the association between victim well-being and proximity to green space.

Living close to a green space is associated with decreased fatigue at 1000 ft (p=0.3), 1500 ft (p=0.01), and 2000ft (p=0.008). Proximity to green space is associated with increased overall psychosocial well-being at 1500ft (p=0.004) and 2000ft (p<0.001). Living close to green space was also associated with increased anxiety in youth victims of violence at 1000ft (p=0.027).

A relationship exists between proximity to green space and youth fatigue and overall well-being following exposure to violence. However, those victims of violence who live closest to green spaces report higher anxiety scores. Subsequent research should focus on determining why proximity to green space differentially impacts youth well-being in the face of violence.

Intentional violent injury was one of the top three leading causes of childhood death in the United States in 2019.1 Rates of violence have been increasing in many cities across the country in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic.2 Experiencing violence or having a family member exposed to violence has a significant impact on childhood well-being.3-6 A recent study found that youth victims of violence had significantly worse emotional functioning, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and peer relationships than age-matched controls who were living with chronic conditions such as obesity and cancer.4

Both individual and community characteristics can promote resilience and positively impact youth physical and mental health.7 Beneficial individual assets include problem solving skills and self-efficacy, while beneficial community assets include “positive friends and safe, supportive schools”.7 Furthermore, evidence suggests that individual resilience can be fostered in children through school-based programming that focuses on teaching them coping skills.8 Additionally, improvements in community assets such as creating green space and improving facades has been shown to reduce firearm related crime and homicides.9 Studies show that neighborhood cohesion can improve well-being and mitigate stress; however, these studies mainly focus on daily stressors.10,11 The relationship between community assets and the well-being of youth victims of violence is not well understood.

Project Ujima is a hospital-based violence intervention program that responds to the identified physical and psychosocial needs of youth and families affected by interpersonal violence. The word Ujima is a principle of Kwanza that signifies working together for a common cause.12 The program targets 350 youth annually who present with firearm or other assault-related injuries to the Children’s Wisconsin Emergency Department/Trauma Center.12 Patient-reported outcome measures (specifically, well-being measures) are collected through Project Ujima to determine each child’s psychological and emotional well-being following exposure to violence and throughout programming. The primary purpose of this study is to determine if there is an association between proximity to protective community assets such as green space and Project Ujima enrollee well-being scores following exposure to violence. Our hypothesis is that there will be an association between well-being scores and proximity to protective community assets. This information is critical to understanding violence-related health disparities among youth who live in areas with frequent exposure to violence.

This study is a retrospective data analysis using existing data from Project Ujima enrollees. Enrollee residence location data was provided in the form of street addresses from the existing database. Street addresses were then cleaned, formatted, geocoded, and mapped using ArcMap version 10.8.1 mapping software. Other variables in the dataset, including gender, race, and age were included in mapping procedures in order to investigate their relationship to the locations associated with the pediatric well-being outcomes. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL™) is a 23-item, validated assessment that measures physical, emotional, social and school well-being as self-reported by youth ages 7-18 to determine overall and psychosocial well-being.13,14 The PROMIS® inventory is National Institute of Health developed tool that is a reliable and precise measurement system for evaluating social well-being and mental health.15 Study population inclusion criteria included an age of 8 to 18 years, and experience as a victim of violent injury (e.g., firearm injury, stabbing, assault). Individuals who were a victim of family violence or sexual abuse were excluded, as were individuals outside the age range of inclusion. Participants were specifically examined in the domains of fatigue, anxiety, depression, peer relationships, and anger. Youth completed all measures in the emergency department (ED) at the time of care-seeking for their violent injury or at home within a month following their hospital visit. PedsQL™ and PROMIS® scores were summarized, along with demographic information of enrollees. A choropleth map of counts of enrollee residence locations within each City of Milwaukee census tract was generated.

Locations for youth, including for those who have experienced gun violence, were obtained using the Master Property (MProp) data file that is available through the City of Milwaukee. Each geographic location within the MProp file contains a land use code which specifies how each parcel within the city is to be used. Categories of land use are available in the MProp file. For the purposes of this analysis, parcels with land use codes that include playgrounds and parks (green space) were analyzed for associations with well-being scores.

To determine the association between proximity to community assets and residence locations of Project Ujima enrollees, a buffer analysis was conducted. Buffers around each address were calculated at 1000 feet (roughly four city blocks), 1500 feet (roughly six city blocks), and 2000 feet (almost eight city blocks). Then, the buffer data were joined separately with the green space location data and the pro-social community asset location data in order to tally the number of each type of location within each buffer as they related to each individual residence address. The buffers were based on Euclidean distances. Regression analyses determined the association between proximity to green space and pediatric well-being scores. All spatial analyses were conducted in ArcMap version 10.8.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) and statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical software, version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s Wisconsin (approval number: 1542261-3).

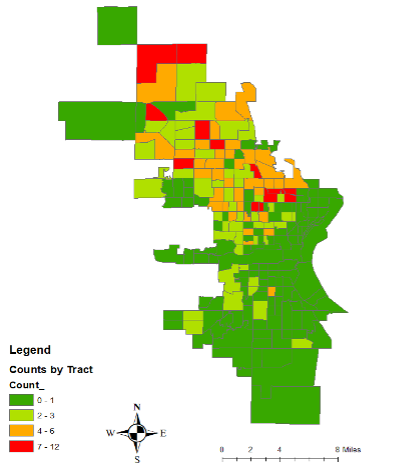

There were a total of 471 Project Ujima enrollees in this sample. Figure 1 displays enrollee residence density by census tract. Table 1 outlines sample characteristics. The mean age of enrollees was 13 years (SD = 3 years). Just over half of enrollees were male (n=239); 79% (n=374) of enrollees identified as Black. The mean total PedsQL™ score for the sample was 67.5 (min = 0, max = 100, SD = 22.2). Other well-being scores are included in Table 2.

Figure 1. Project Ujima Residences by Census Tract

Enrollee residence density by census tract for the 471 Project Ujima enrollees.

Table 1: Sample demographics (n=471)

Characteristic | n | Percent of total |

Race/Ethnicity Black/African American White Hispanic American Indian Other Unknown |

374 48 35 2 9 3 |

79.4 10.2 7.4 0.4 1.9 0.6 |

Sex Male Female Unknown |

239 230 2 |

50.7 48.8 0.4 |

Age | Mean = 13.4 | SD = 3.01 |

Table 2: Pediatric Well-Being Scores (PedsQL™ and PROMIS®)

Score (ranges 0-100) | Healthy Norm Score | Mean | SD |

Total well-being | 83.9 | 67.5* | 22.2 |

Psychosocial well-being | 81.8 | 63.3* | 22.6 |

Fatigue | 50 | 40.1* | 21 |

Anxiety | 50 | 50.3 | 13 |

Depression | 50 | 50.7 | 13.2 |

Peer relationships | 50 | 44.6* | 12.7 |

Anger | 50 | 53* | 16.1 |

Table 3: Proximity-Based Regression analysis

| Coefficient | Std. err. | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval |

Green Space Locations – 1000 feet | ||||

Fatigue | -.003 | .001 | 0.03* | -.006, -.000 |

Anxiety | .006 | .003 | 0.03* | .001, .012 |

Green Space Locations – 1500 feet | ||||

Total Well-being | -.013 | .006 | 0.02* | -.025, -.002 |

Psychosocial | .016 | .006 | 0.004* | .005, .028 |

Fatigue | -.005 | .002 | 0.01* | -.009, -.001 |

Green Space Locations – 2000 feet | ||||

Total Well-being | -.024 | .008 | 0.002* | -.039, -.009 |

Psychosocial | .028 | .008 | 0.000* | .013, .043 |

Fatigue | -.007 | .003 | 0.008* | -.013, -.002 |

The buffer analyses allowed for a tallying of green spaces and pro-social organizations within 1000 feet, 1500 feet, and 2000 feet of each Project Ujima enrollee address. All participants included in narrower range buffers are included in the wider range buffers. The 1000-foot buffer analysis demonstrated that 70 (14.9%) Project Ujima enrollees lived within 1000 feet of green space. The 1500-foot buffer analysis demonstrated that 144 (30.6%) Project Ujima enrollees lived within 1500 feet of green space, and the 2000-foot buffer analysis showed that 214 (45.4%) Project Ujima enrollees lived within 2000 feet of green space.

Regression analyses (R2 = 0.03) revealed significant associations between well-being scores and proximity to green space. Specifically, living close to a green space is associated with decreased fatigue at 1000 ft (p=0.3), 1500 ft (p=0.01), and 2000ft (p=0.008). Proximity to green space is associated with increased overall psychosocial well-being at 1500ft (p=0.004) and 2000ft (p<0.001). Living close to green space was also associated with increased anxiety in youth victims of violence at 1000ft (p=0.027).

Our results indicate there is an association between proximity to green space and youth victim of violence total well-being, psychosocial well-being, peer relationships, and anger. These findings support and add nuance to existing literature that indicates neighborhood green space can improve the emotional well-being of children.16-18 One particular study found that access to green space promotes resilience in children, which is particularly applicable to our study population who have previous exposure to violence.16

One of the most significant findings was that proximity to green space was associated with improved psychosocial well-being of youth in the 1500- and 2000-foot buffers and was associated with reduced fatigue across all analyzed buffers. This is supported by a meta-analysis from 2010 showing that exposure to natural environments such as green space reduces fatigue and increases attention.19

Additionally, our findings note an incremental benefit of proximity to green space in the context of alleviating fatigue with increasing proximity to green space. These data infer that for youth victims of violence can benefit in terms of improved energy at a buffer of eight blocks.

The relationship between reduced fatigue, increased psychosocial well-being, and proximity to green space amongst youth victims of violence has significant public health and urban planning implications. These data provide support for policies that enhance neighborhood efforts for greening in urban areas in order to improve youth psychosocial health, particularly as it relates to vulnerable populations who have been exposed to violence.

It was unexpected that participants’ place of residence being within 1000 feet of green spaces was associated with increased youth anxiety. One potential explanation for this could be that green spaces serve as a space where crime can occur in urban neighborhoods, which may result in increased anxiety in youth who live nearby.20 Conversely, more data exists supporting the alternative –that green space generally has a reductive effect on urban crime.21-23 Interviewing participants about their experiences at these locations and the cause of their anxiety could provide helpful insight into these results. Further analysis into the local context of green space and crime rates could further elucidate this association. If the local context is driving the association between green space and anxiety in youth victims of violence, public health efforts can address ways to make green spaces less anxiety inducing.

These results are generalizable to other urban areas experiencing high levels of community violence that impacts youth. One limitation of this study is that the use of community assets is not collected from participants; therefore, an association cannot be made between participant usage of community assets and their well-being scores. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of this study prohibits us from determining if proximity to green space has a beneficial impact as participants continue to recover from exposure to violence. Since we do not collect information on location of injury, we are not able to determine whether enrollees were injured in parks or on playgrounds, which impacts conclusions drawn between increasing anxiety related to proximity to green space.

Lastly, our study’s R-squared value was low, indicating that youth well-being scores could not be explained entirely by the proximity to green space and pro-social organizations. However, our regression analysis controlled for demographic variables, including age, sex, and race. Further investigation is needed to determine which factors play a role in youth well-being following exposure to violence. Additionally, qualitative studies with youth who are exposed to violence could provide important information on youth perception of the green spaces in their neighborhoods.

This study provides evidence that proximity to green space has a positive impact on fatigue and psychosocial well-being in youth victims of violence. Subsequent research should focus on determining why proximity to community assets are related to youth fatigue, anxiety, psychosocial well-being, and total well-being scores. Further research should also focus on whether proximity to other community assets can improve the well-being of children exposed to violence. Policy solutions should also focus on increasing access to green spaces in urban areas.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Ashley Hollo is a first year pediatric resident at the University of Colorado. She attended medical school at the Medical College of Wisconsin and received a Master of Public Health from The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her scholarly work is focused on health policy and injury and violence prevention.

Sara Kohlbeck, MPH is the Director of the Division of Suicide at the Comprehensive Injury Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin

Mark Nimmer has 8 years experience in data analytics and and a passionate interest in using his expertise to measure and evaluate programs and services for youth victims of violence.

Medical Director of Project Ujima and Vice Chair of Diversity and Inclusion in the Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.